This page in a series on ritual images again concerns Gaoluo (see top Menu). It’s worth reading along with my pages on the New Year’s rituals and Other ritual groups in Gaoluo, as well as Donors’ list 2: Gaoluo.

Apart from their ritual manuals and gongche solfeggio scores, all four ritual associations in North and South villages of Gaoluo have collections of images, including god paintings, diaogua hangings and donors’ lists, from various stages since the 19th century. Here is a selection (for details, see my Plucking the winds, pp.43–56, 203–205, 277–82 and passim).

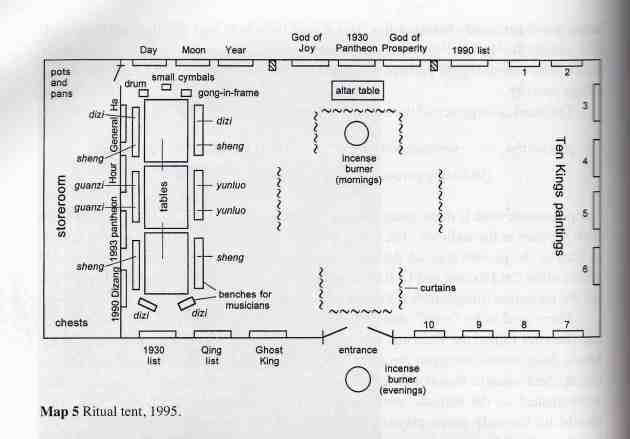

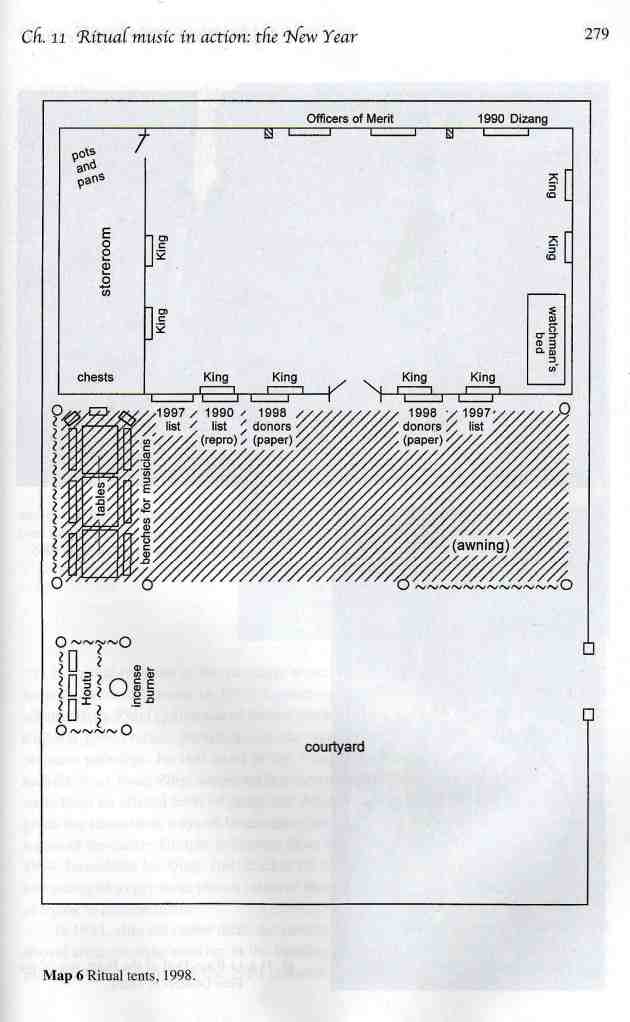

By 1995, the associations had a patchwork of ritual artefacts made at different times over their history—just as in English churches, indeed. Since 1980, unlike many villages in north and south China, and indeed nearby (such as Niecun just across the river), Gaoluo has not sought to build new permanent temples. But the previously bare and unprepossessing ritual buildings, once fully adorned, become a place of great beauty, a fitting backdrop for the associations’ performance.

South Gaoluo yinyuehui

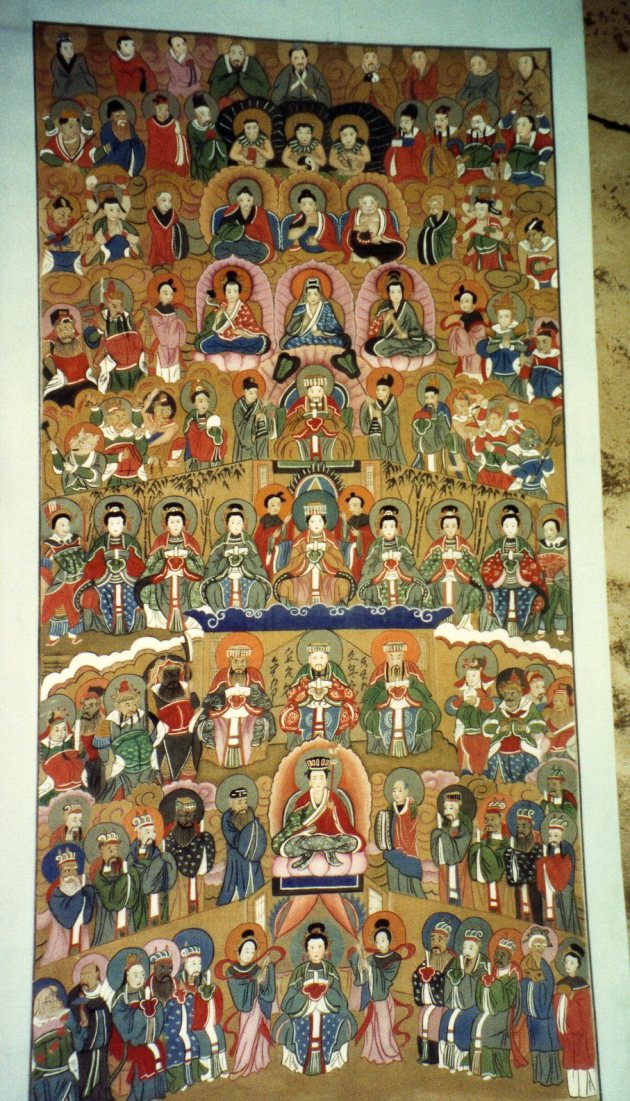

In the ritual building the central painting of the central trinity of god paintings was the pantheon. Until 1996 the association still kept a precious old pantheon, said to have been painted along with the diaogua hangings in 1930.

Foot of 1930 pantheon, with old qing bowl on altar table.

1930 pantheon flanked by Caishen (right) and Xishen. New Year 1995.

It was flanked to its north (left) and south (right) by the God of Prosperity (Caishen) and the God of Joy (Xishen). The goddess Houtu and the earth god Tudi should be to the south of the pantheon, the Ten Kings of the underworld to the north. There used to be a wooden tablet (paiwei) to the Dragon Kings (Longwang), placed centrally.

An early donors’ list, which we were told was made in the 19th century, was so faded by the time we saw it in 1995 as to be totally illegible. By then their earliest datable artefact was a fine old ritual curtain from New Year 1892, donated by “faithful disciple” Heng Jun, a prominent member of the leading lineage:

The central characters read “Buddha realms”; the couplets on either side read “Seven spells Ahuiban” [meaning unclear] and “The Three Treasures Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha”.

The association also had fine old paintings of the Four Officers of Merit (Sizhi Gongcao 四值功曹): the god of the Year (Huang Chengyi), Moon (Liu Hong), Day (Zhou Deng), and Hour (Li Bing), respectively, as in the novel The Ennobling of the Gods. These paintings, like that of the God of Prosperity, are said to have survived the Houshan fire in the late 19th century, and were hidden from the Red Guards in 1966.

Li Bing, God of the Hour, one of the Four Officers of Merit.

Hung in the midst of the Four Officers of Merit there were also old paintings of Huoshen the God of Fire and one of the Two Generals Heng and Ha; and a much faded but all the more sinister King of Ghosts. All these paintings were displayed at New Year 1995.

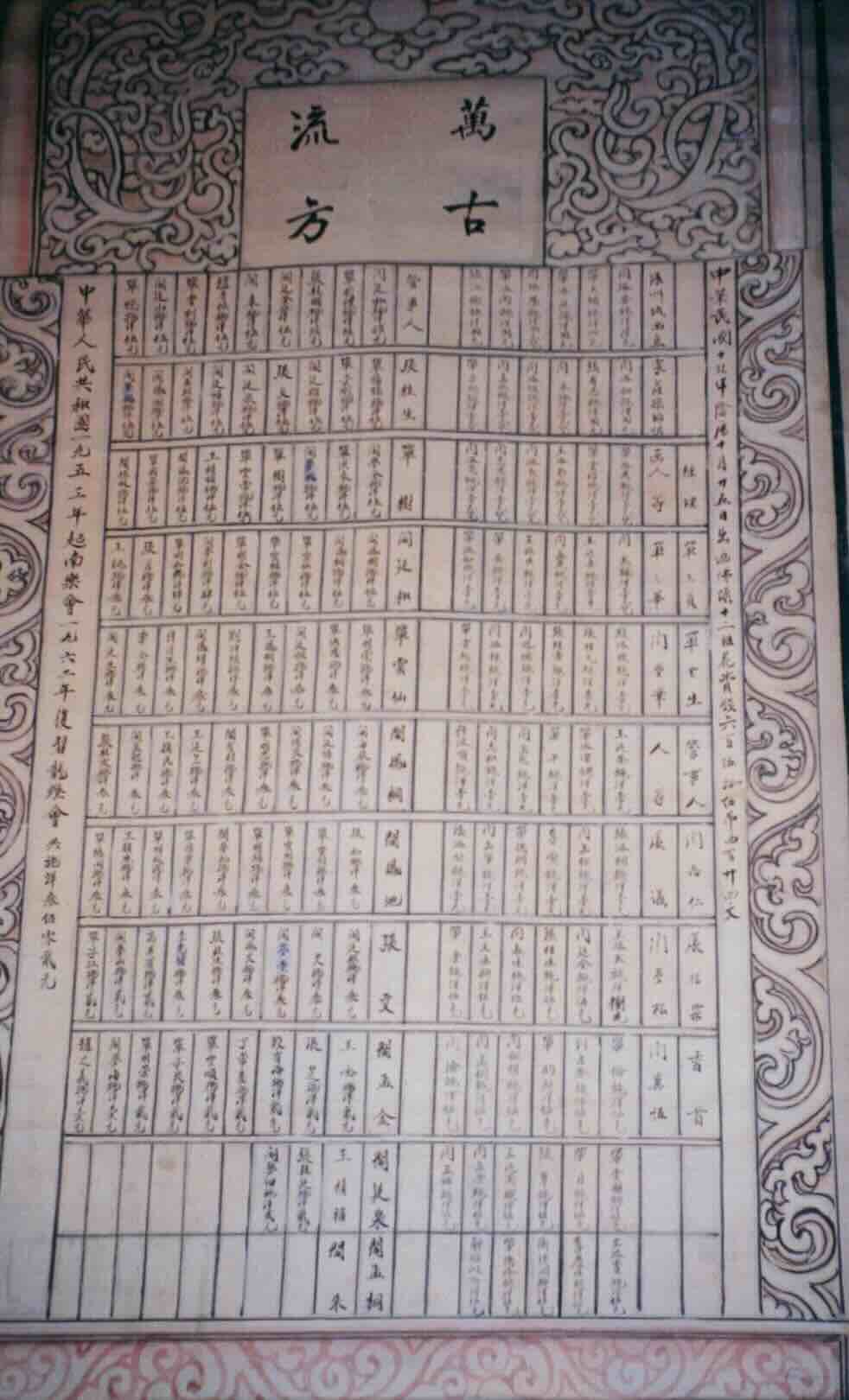

Ghost king, one of the association’s oldest paintings.

A donors’ list, which we saw hung out at the 1995 New Year’s rituals, is said to date from the late 19th century, but alas it was so faded by the time we saw it displayed as to be totally illegible. Instead, most handsome of the ritual artefacts on display in the lantern tent was the 1930 donors’ list (Plucking the winds, pp.50–56 and n.70, 282)—apparently the only such list that we have found in the region which has survived from before Liberation:

1930 donors’ list, South Gaoluo, 1989.

During 1930 both ritual associations in South Gaoluo undertook a refurbishment of their ritual apparatus, commemorated in handsome donors’ lists. There may be several explanations for this initiative. It is possible that some of their old god paintings had been lost or were just too decrepit. Ritual icons may have been destroyed by the village Catholics in 1899 in the prelude to the Boxer massacre; we also heard a story that old paintings had been destroyed in a fire on the Houshan mountain about thirty years before the Boxer incident. A more likely reason may have been a brief restoration of peace in the area from 1930, after many years of fierce fighting between warlords.

However, I very much suspect that the major incentive for the 1930 initiative in South Gaoluo was competition with the renewed energy of the Catholics. No doubt the conflict over the New Year’s rituals which led to the 1900 Boxer massacre was still in people’s minds. In 1996 venerable Shan Zhihe summed up the competitive spirit: “What it meant was, you believe in your Catholicism, we’ll uphold our Buddhism!”

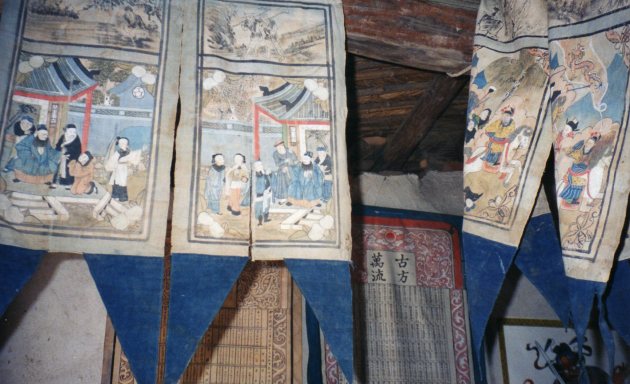

As in many villages, apart from the god paintings to be hung inside the ritual building, the Gaoluo associations also had beautiful sets of ornamental diaogua “hangings” to be displayed outside each house along the alleys throughout the village at New Year. Each group (called “one road” yilu) consisted of four paintings. The 1930 donors’ list of our South Gaoluo ritual association commemorated the commissioning of 43 such groups from the painter Sun of Doujiazhuang village in Zhuozhou county just north. 108 of these depictions were still on display in the alleys during our first visit at New Year 1989. They depicted the stories of the goddess Houtu, the Three Kingdoms, and scenes from The Ennobling of the Gods, notably the spectacular battles for the city of West Qi.

For New Year these paintings were hung along both sides of the alleys, a magnificent spectacle—people used to come from other villages to admire them. Tradition goes that the old ritual paintings which had survived the Houshan fire in the 19th century—the four Officers of Merit and the God of Prosperity, which were also preserved until 1996—were painted meticulously over a considerable period, but that Painter Sun’s 1930 paintings were rather less beautiful since he did them rather too quickly; still, to us they in turn had a spiritual beauty which yet more recent paintings could not attain. The village alleys were further illuminated at New Year by beautiful “palace lanterns”.

The 1930 list is entitled Wanshan tonggui (“The myriad charities return to the same source”). By 1995 this list too was much deteriorated, but fortunately on our first visit in 1989 I had taken good photographs, copies of which I later sent to the association. Accompanying all our enquiries into the stories of our friends’ fathers and grandfathers, the 1930 list truly came to life.

The list records 92 heads of households, surely consisting of most of those then living in the southern half of South village which the association served, though some were doubtless too poverty-stricken to be able to afford even a minimal contribution. For all the beauty of the list, many villagers (including all the womenfolk) were unable to read it.

The donations, ranging from 6 yuan to 5 jiao, totalled 109.83 yuan; the cloth cost 24 yuan, the paintings 61.5 yuan, and other expenses amounted to 33.83 yuan, leaving debts of 9.5 yuan. The yuan here denotes the silver dollar; in 1996 village historian Shan Fuyi reckoned it would be worth about 30 yuan at today’s rates, so the 109 yuan might be equivalent to over 3,000 yuan today.

Five “managers” of the association are named at the head of the list: Cai Lin, Cai Ze, Shan Xue, Shan Chang, and Shan Futian. As their descendants recalled in the 1990s, all were prominent figures in the village, some of whom were also active as ritual performers (sketches in Plucking the winds, p.54).

After the tribulations of the following decades, local litterateur Shan Fuyi made a new donors’ list in 1990, naming 270 heads of households:

It is over 150 springs and autumns since our village’s sacred society (shenshe) the Southern Lantern Association, was established through the charitable donations of our people in the illustrious Daoguang years of the former Qing dynasty. As the years went by, the ritual hall became decrepit, but [our name] had extended as far as the UK. So it was the brutishness of our own village which was losing face for the Chinese people. Thus we decided to hold up our heads and determined to rebuild the hall. We went round all the families of the friends of the association and obtained over 1,300 yuan in renminbi. Zhang Yu supplied all electrical equipment and labour for the lighting; Heng Fuzhong, Sun Wenjiang, Cai Shuqing, Shan Caiwang, Shan Shusen, Wang Qingshan, Shan Futang, Shan Zhidong, Shan Xingze, Shan Xingfen, Shan Yuxiang, Yan Haiyi, Ding Shun, and Shan Zhitong supplied carts, horses, and labour for transporting materials. We also obtained the support of the village brigade, and work was completed in 1989. Those responsible: He Qing, Li Shutong, Cai An, Shan Yude.

The budget of 2,000 yuan exceeded our funds by several hundred, equivalent to 13 jin of grain or cloth per yuan. “With the will of the people, the wall will be completed by itself”.

1st moon, 1990.

By the 1990s the most important deities worshipped by the villagers were Houtu the child-giving goddess and Caishen the God of Wealth, succinctly indicating villagers’ mundane concerns in enlisting divine help, as well as Dizang and the Ten Kings of the underworld.

Though some ritual associations had again started making the Houtu pilgrimage in the 3rd moon to the Houshan mountains to the northwest, Gaoluo villagers now made the pilgrimage only in small groups. In fact people I asked didn’t consciously see the Houtu cult as having gained new energy since the 1980s in response to the birth-control policy, which to me is clear. Sadly, by 1995 the association had no public depictions of Houtu and her story, apart from the Houtu scroll, although the Southern Music Association still had several.

Some of the old ritual paintings had been sacrificed to the rampaging Red Guards in 1966; some were burnt on the spot, others (including the 1930 Ten Kings paintings and an even older pantheon) were said to have been handed over by the work-teams to the commune and thence to the county Bureau of Culture, which sent them to the museum at the regional capital Baoding. But the villagers knew nothing of their fate until the late 1980s.

Remarkably, some of the paintings which had ended up in the Baoding museum were still there in 1996. Fortuitously, during the 1980s the South Gaoluo villager Heng Zhiyi (gifted son of former landlord Heng Demao) had become head of the Cultural Preservation Department at the museum. Thinking that he recognized the precious paintings, he sent word to the village; the musicians were naturally keen to recover them. Heng Zhiyi suggested that they should ask the county Bureau of Culture to write them an official letter of proof, but the musicians thought this unlikely to succeed, given the inscrutable ways of bureaucracy and the sensitive and perhaps “superstitious” nature of the matter. Upright policeman Shan Rongqing was active in liaising, as ever; by 1994, formidable He Qing, still shocked by being conned out of the diaogua hangings, had managed to get some photos taken of the paintings, but as yet there was no question of trying to reclaim them.

In 1993, after the recent thefts, the association commissioned a new pantheon from an artist working at the Baoding museum, though they later recovered the old one:

Pantheon, Ma Yusheng 1993.

Quite soon after the 1980 restoration Shan Fuyi had made a painting of Dizang, god of the underworld, used for funerals and also at New Year. Its five rows depict the hierarchy of deities presiding over the passage to the other world: Dizang, the Ten Kings, the city god Chenghuang, the Three Pures (Sanqing), and the Five Ways (Wudao):

Dizang and underworld hierarchy, Shan Fuyi c1983. Funeral, 1995.

The separate paintings of the Ten Kings of the underworld were also displayed at New Year. Shan Fuyi was alone in retailing a story that the old Ten Kings paintings had been burnt in a lightning fire some time before 1875, along with their ritual tent at the mountain temple of Houshan during the 3rd moon pilgrimage. The 1930 Ten Kings paintings had been taken off by the Red Guards in 1966, and the new series was painted in 1993 by Wu Jingrong of East Xin’gao village, who had also recently painted a set for North Gaoluo. The function of the New Year’s rituals, to ensure correct relations with the gods, ghosts, and ancestors, explains the displaying of these paintings.

For the New Year in 1994 and 1995 the association also displayed beautiful old ritual curtains which covered the main entrance, the central altar before the trinity of god paintings, and the entrances to the side rooms. The central curtain, presented by one Heng Jun in the New Year of 1892, had the two characters “Buddha realms” (Fo jing) embroidered in the middle; its couplets on either side read “Seven spells (Qizhou) Ahuiban” (meaning unclear) and “The Three Treasures: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha”. The two handsome donors’ lists from 1930 and 1990 were also proudly on display.

New Year 1989.

Diaogua hangings were displayed along the alleyways during the New Year’s rituals. Each group conststed of four paintings (yilu 一路 “one road”). The 1930 donors’ list commemorates the commissioning of forty-three such groups from the Painter Sun from Doujiazhuang village in Zhuozhou nearby. 108 such images were still on display during our visit at New Year 1989, depicting the story of Houtu, the Three Kingdoms, and scenes from The Ennobling of the Gods, notably the spectacular battles for the town of West Qi—the Star Wars of its day.

After the Great Leap Forward and the famine, the revival of the early 1960s (however short-lived) was significant for the transmission of traditional culture. Not only were the ritual associations reinvigorated (cf. the Guanyin Hall donors’ list below), but the village opera troupe also revamped their equipment (Plucking the winds, pp.143–5). Like the ritual associations, they too sought donations from all the village households, shown on Shan Fuyi’s donors’ list dated 2nd moon of 1964:

The list is headed with the title “Flowers encounter spring rain”, and couplets which adorn it show the misplaced optimism of the time:

Auspicious snow flurries around as spring shoots are sturdy and thriving

and

Timely rain descends throughout as the hundred flowers start to blossom.

The text gives a brief summary of the troupe’s history:

It is now seven years since our village established its opera troupe, but it has only had energy the last two years. While all the performers have an abundance of energy, the opera costumes were not sufficient. Fortunately the county opera troupe has sold off part of its costumes at a reasonable price, just right for us, a great opportunity. For this, commune members of the whole village have made donations in large numbers, so that the sum required has been amply met. Truly, “when hearts are united no enterprise is difficult”, and “the strength of the people returns to Heaven”. Below we now list the amounts donated by households to provide a record for display.

Note that the list nonchalantly dates the founding of the troupe back only as far as the 1957 conversion to bangzi—before that, they told us, it was “only” political, not a real opera troupe!

North Gaoluo yinyuehui

The yinyuehui of North village had a similar history. All their ritual paintings were burnt in the Cultural Revolution, including their pantheon, the Ten Kings, Eighteen Arhats, Four Heavenly Kings, the Two Generals Heng and Ha, God of Long Arms (Changbei shen), and the Four Officers of Merit, as well as their own set of diaogua hangings. The only artefact they managed to preserve was the fine ritual curtain from 1912, which veils the Buddha painting of Sakyamuni (Rulai) “to show respect”. In 1990, stimulated by our visit, they had a series of new ritual paintings made, notably the Ten Kings:

Shengguan before the Ten Kings, lantern tent 1993.

Yama King, from 1990 Ten Kings paintings.

Crossing the Bridges, detail from Qinguang image of 1990 Ten Kings set.

Their donors’ list for these new paintings (again, see under Gaoluo: other ritual groups) is entitled “Enduring fragrances of myriad ages” (Wan’gu liufang). At the top are the names of twelve guanshi organizers. The inscription reads:

Our village North Gaoluo Blue Banner Holy Association is reckoned to have been transmitted for several hundred springs, but has previously encountered warfare and barren years, and has been in decline; even as recently as the Cultural Revolution, all of our cultural relics were completely destroyed. The villagers have been lamenting this ceaselessly. This spring, with abundant rain water and auspicious nature, the people’s sentiments are inspired, mindful of restoring the sacred association, calling on the common people to support it with generous donations. We have made an inscription to record this, in the hope that the reputation of the customs of this village will be transmitted for a thousand ages.

Time: People’s Republic of China, 1990 AD.

The inscription is followed by a list of 147 heads of households, who had donated between 50 and 2 yuan.

South Gaoluo Guanyin Hall (Eastern Lantern Association)

This association has beautifully embroidered old ritual curtains with these inscriptions:

Great Qing, Guangxu [era, 1875–1908]

Newly made in Great Qing, Guangxu 34th year (1907), South Gaole village Guanyin Hall Association.

Ritual curtain, 1907.

We wondered if these curtains could even commemorate the founding of the temple, but in 1996 we deduced that the association at least (if not the temple) must be much older than this, when the musicians brought out two fine old “precious scrolls”, to Baiyi (Guanyin) and Dizang, officiating over birth and death respectively – the musicians say they also used to have a Houtu scroll, though the Baiyi scroll fulfils a similar function. The Dizang scroll is dated 1710, apparently the earliest ritual artefact we have from Gaoluo, though the inscription gives no place or name. Their funerary manual is similar to but more complete than the 1903 manual of the Music Association.

In 1930, competing with the Catholics, like the Music Association, the Guanyin Hall association commissioned new Buddha images, including some fine Houtu paintings which still adorn the ritual building at New Year. For their 1962 revival as a “Dragon-Lantern Association” they sought donations, and made a donors’ list. They used the same cloth on which the 1930 list had been written; the 1930 list is on the right, the 1962 list continues to the left:

The 1962 section records:

1952 under the People’s Republic of China, established the Southern Music Association; summer of 1962, practised the Dragon Lantern Association and raised 302 yuan.

It first records twelve guanshi organizers, and then lists eighty-three donors (households), who gave sums from 10 to 1 yuan. The sum raised from the association’s constituents, who were fewer than half of those of the popular village-wide opera troupe which raised donations in 1964, is impressive.

Houtu painting, 1930, by Painter Sun.

Diaogua hangings, with donors’ lists behind, lantern tent 1995.

Diaogua hanging, Wang Laoguo, 1930s.

They made a new donors’ list in 1992 for the rebuilding of their own ritual building:

* * *

What emerges from all this is that, just like the ritual soundscape, ritual artefacts are no mere timeless gems of “heritage”; rather, in the way that they are actually used they reflect a constantly-adapting society.