Gauthier, gamelan, and Gershwin

I can’t remember how I came across the name of Éva Gauthier (1885–1958) and the story of how she presented arrangements of Javanese music in her concert recitals.

By the late 19th century the sounds of gamelan were regularly heard at grand exhibitions in the West; Paris 1889 (Exposition Universelle), Chicago 1893 (Columbia Exhibition), and San Francisco 1915 (Panama–Pacific International Exposition) all had a “Javanese village”.

By contrast with Berlioz’s aversion to the music of the Mystic East, Debussy was entranced by the gamelan he heard at the 1889 Exposition. He wrote to a friend in 1895 of “the Javanese music, able to express every shade of meaning, even unmentionable shades… which make our tonic and dominant seem like ghosts, for use by naughty little children.” And in 1913, in a much-cited passage:

There used to be—indeed, despite the troubles that civilization has brought, there still are—some wonderful peoples who learn music as easily as one learns to breathe. […] Their traditions are preserved only in ancient songs, sometimes involving dance, to which each individual adds his own contribution century by century. Thus Javanese music obeys laws of counterpoint which make Palestrina seem like child’s play. And if one listens to it without being prejudiced by one’s European ears, one will find a percussive charm that forces one to admit that our own music is not much more than a barbarous kind of noise more fit for a travelling circus.

(Ravel is also sometimes said to have been impressed by the gamelan at the 1889 Exposition, but he was only 14, and I haven’t yet found a source.)

As to gamelan studies in later years, Michael Church devotes chapter 12 of Musics lost and found to the immersion of Jaap Kunst (1891–1960) and Colin McPhee (1900–1964) in the musics of Java and Bali. On his return from Indonesia to Amsterdam in 1934, Kunst established gamelan as a major theme in ethnomusicology. The Canadian-American composer McPhee lived in Bali through the 1930s; he found the engaging A house in Bali easier to write than his monumental study of the island’s music: “I did not live in Bali to collect material. I lived there because I wanted to, for the pleasure of it”. As Church comments,

he disdained the paraphernalia of scholarship, wanting to purge the book of “all stupid jargon-like aeophones [sic], idiophones beloved by Sachs and Hornbostel”. Yet as Oja points out, his approach to research was fastidious and scholarly.

Such pioneers lay the groundwork for the later gamelan craze; since the time of Mantle Hood few self-respecting ethnomusicology departments are without their own gamelan…

* * *

Even before Kunst, the French-Canadian mezzo-soprano Éva Gauthier was already promoting the music of Java (besides wiki, I have consulted Matthew Isaac Cohen, “Eva Gauthier, Java to jazz”).

Éva Gauthier, 1905. All images from wiki.

Éva Gauthier, 1905. All images from wiki.

In 1910, disillusioned by being replaced in the opera Lakmé at Covent Garden, she travelled to Java, where she inconsequentially married a Dutch importer and plantation manager. Until 1914 she was based in Surakarta; besides performing there, in 1911 she toured Delhi, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Peking, followed over the next two years by Japan, Siam, and India.

But while in Surakarta Gauthier was granted permission to live in the Kraton palace to study its court music. She gained an introduction to this world through the composer and pianist Paul Seelig (1876-1945), former conductor of the royal band, chronicler of gamelan and kroncong. As she learned the basics of gamelan theory, Gauthier’s relations with the all-male gamelan musicians of the court were mediated through the royal wives.

She was taught, for example, that the drum was the “chef d’orchestra”, and that the vocal part “is merely a tone colour in the ensemble, and the singer’s voice counts as another instrument in the orchestra”.

Here’s film footage of a performance at the Kraton from 1912 (part of an interesting playlist):

And here’s the album Court music of Kraton Surakarta (King Records), recorded in 1992:

Gauthier’s sojourn at court also involved, um, International Cultural Exchange:

I sang to them a bit of colorateur and they thought the screaming on the high notes was hideous; they thought I was going to burst. Then I sang to them a melody. But they looked bewildered. They could not grasp it in the least. Then I sang Debussy to them, and they went into raptures.

Anyway,

She became such an enthusiast of Javanese performance that she hatched a plan to produce a tour of Javanese dancers and gamelan to Europe. She was convinced that the srimpi dance would captivate European audiences as much as it had her.

When this plan was thwarted by World War One, Gauthier moved to New York, and began to give recitals of arrangements by Paul Seelig and Constant Van de Wall, inserting short talks on Javanese courtly culture into her programmes. Her 1914–15 recordings of two songs were reissued in 1938:

For a gruelling vaudeville tour of the States she teamed up with the exotic dancer Regina Jones Woody (“Nila Devi”) with an item called Songmotion. As the latter recalled,

We were booed, laughed at, and made targets for pennies and programs. Almost hysterical, Eva and I changed into street clothes and sat down with Mr. Smith [the stage manager] and the conductor to discuss what to do. We had a fifty-two-week tour ahead, but if this was a preview of audience reaction, the Gauthier-Devi act wouldn’t last two minutes in a big city.

The stage manager, Mr Smith, was outspoken. He took Madame Gauthier apart first. “Take off that horse’s head thing you’re wearing and get rid of that sarong with its tail between your legs. Scrap that whiny music. You’re a good-looking woman. Put on your best evening gown, sing the Bell song from Lakmé, and you’ll get a good hand”. Madame promptly fainted.

On being revived, she stalked out of the room, announcing, “We’ll close before I prostitute my art”.

I came next. According to Mr. Smith I look bowlegged as I moved my feet and legs in Javanese fashion. Even he had to laugh. My native costumes were ugly. Why did I have four eyebrows? And if I could really dance, why did I just wiggle and jiggle about? Why didn’t I kick and do back bends and pirouettes?

Substituting Orient-inspired songs by composers such as Ravel and Granville Bantock, they only retained two songs by Seelig and Van de Wall. Gauthier withdrew from the year-long tour after five months, but for Songmotion in 1917, with Nila Devi no longer available, she found another dance partner in Roshanara (Olive Craddock!). This led them to perform in Ballet intime, an altogether more classy affair directed by Adolf Bolm, formerly of the Ballets Russes.

Having premiered Stravinsky’s Three Japanese lyrics in 1913, Gauthier loaned her Java notebooks to Ravel and Henry Eichheim. In November 1917 she premiered Five poems of ancient China and Japan by the talented young Charles Griffes (1884–1920).

and that same year she supplied him with material for his Three Javanese songs:

Much drawn to both French modernism and American popular music, in 1923 Gauthier gave a seminal recital of “Ancient and modern music for voice” at the Aeolian Hall in New York—an early challenge to the boundaries between high and low cultures. In the first half she sang pieces by Bellini and Purcell, as well as modernist works by Bartók, Hindemith, Schoenberg, Milhaud, and others. The second half was still more daring, including pieces by Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, and George Gershwin (who accompanied these items on piano). This was the first time Gershwin’s music was performed by a classical singer in concert, and led directly to the commissioning of Rhapsody in blue (1924) and his later jazz-classical syntheses.

Through the 1920s Gauthier often performed her “Java to jazz” programme, which typically began with her Seelig and Van de Wall songs, continuing with Beethoven, Bliss, Debussy, and Ravel, and ending with Gershwin, Berlin, and Kern. **

Birthday party honouring Maurice Ravel in New York, 8th March 1928.

From left: Oscar Fried, Eva Gauthier, Ravel at piano, Manoah Leide-Tedesco, George Gershwin.

* * *

Griffes is cited as saying “In the dissonance of modern music the Oriental is more at home than in the consonance of the classics”. Cohen again:

Gauthier’s encounters with traditional Asian music, and particularly Javanese and Malay song, at a pivotal point in her career opened her mind to the diversity of world music and made her rethink her cultural values. As she remarked, “It was actually a serious study of all Oriental music that enabled me to understand and master the contemporary or so-called “modern music”.

For more on Indonesia, cf. Margaret Mead (under The reinvention of humanity), Clifford Geertz, and Frozen brass. For more Debussy, click here and here.

* For the riches of regional traditions, note the 20-CD series Music of Indonesia (Smithsonian Folkways, masterminded by Philip Yampolsky)—this playlist has a sample.

** From the days before newspaper typesetting rejoiced in the terse and gnomic, the wiki article on Gauthier cites a 1923 headline in the Fargo Forum:

Eva Gauthier’s Program Sets Whole Town Buzzing: Many People Are of Two Minds Regarding Jazz Numbers—Some Reluctantly Admit That They Like Them—Others Keep Silent or Condemn Them

Cf. the over-generous title of an 1877 book cited by Nicolas Slonimsky (in note here). And this roundup of wacky headlines.

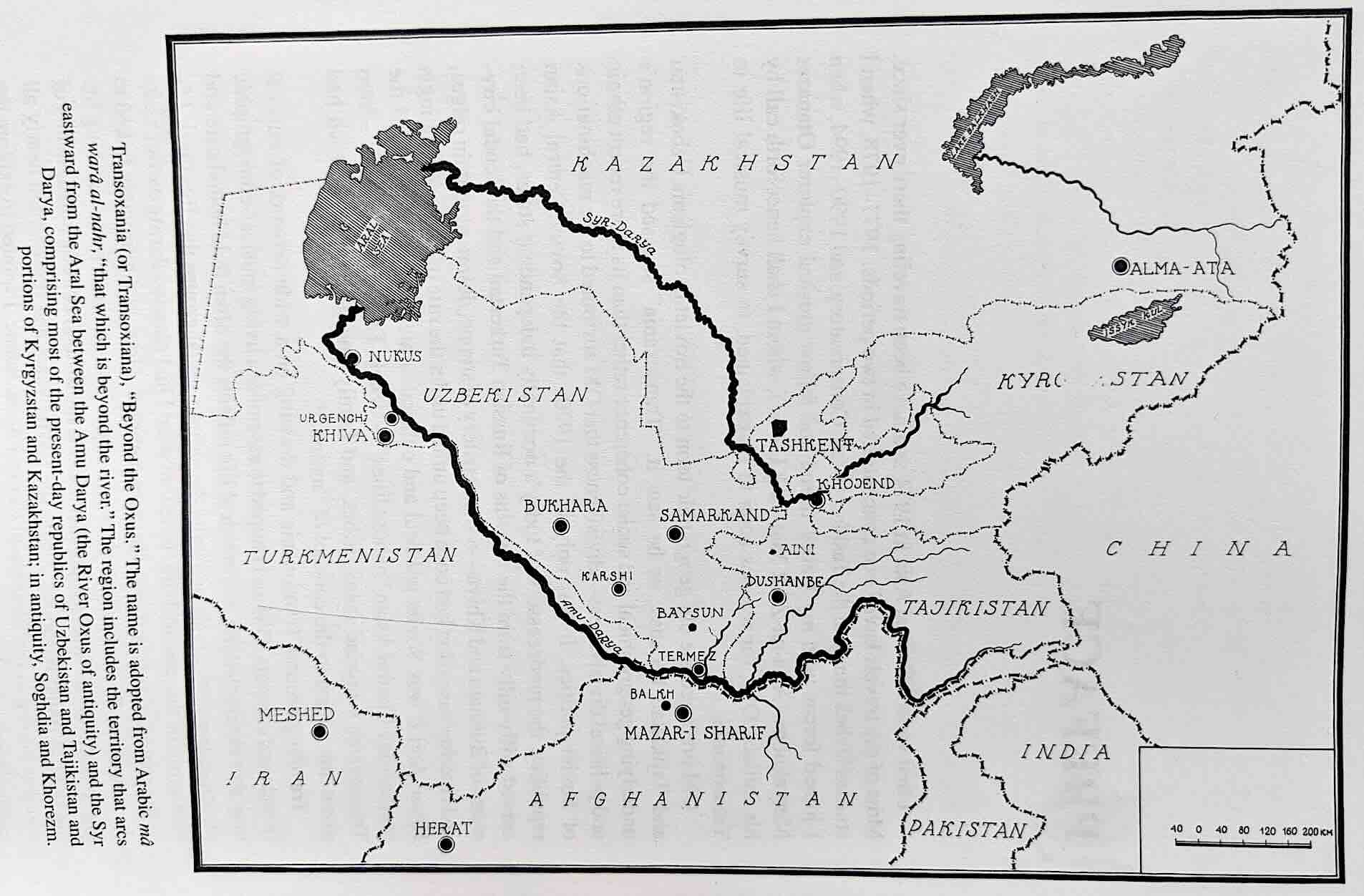

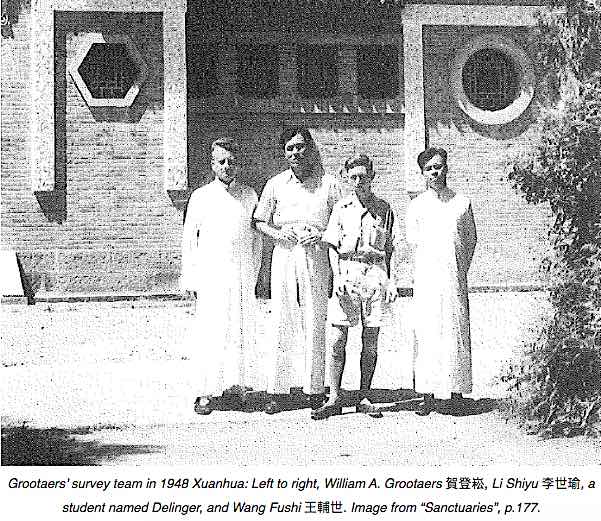

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

We get to hear some of the

We get to hear some of the

The film does justice to Raymond Chandler’s brilliant prose style. Roger Ebert, always a perceptive reviewer, made some

The film does justice to Raymond Chandler’s brilliant prose style. Roger Ebert, always a perceptive reviewer, made some

Nobody embodies more fully the connection between the African-American spiritual, the blues, R&B, rock and roll—the way that hardship and sorrow were transformed into something full of beauty and vitality and hope. American history wells up when Aretha sings. That’s why, when she sits down at a piano and sings “A Natural Woman”, she can move me to tears […] because it captures the fullness of the American experience, the view from the bottom as well as the top, the good and the bad, and the possibility of synthesis, reconciliation, transcendence.

Nobody embodies more fully the connection between the African-American spiritual, the blues, R&B, rock and roll—the way that hardship and sorrow were transformed into something full of beauty and vitality and hope. American history wells up when Aretha sings. That’s why, when she sits down at a piano and sings “A Natural Woman”, she can move me to tears […] because it captures the fullness of the American experience, the view from the bottom as well as the top, the good and the bad, and the possibility of synthesis, reconciliation, transcendence.

The balance of joy and pain—

The balance of joy and pain—

[2]

[2]

Eliza Carthy with her mother Norma Waterson.

Eliza Carthy with her mother Norma Waterson.

Source.

Source.

Dr King’s supporters point in the direction of the shooting.

Dr King’s supporters point in the direction of the shooting.

With the Mayor of Philadelphia.

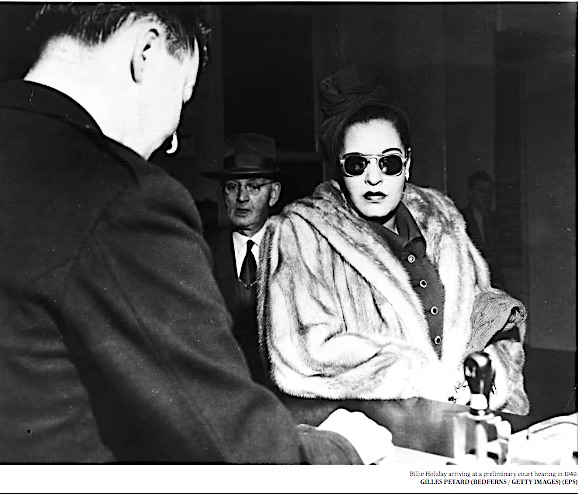

With the Mayor of Philadelphia. Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Panorama of the damage soon after the massacre.

Panorama of the damage soon after the massacre.

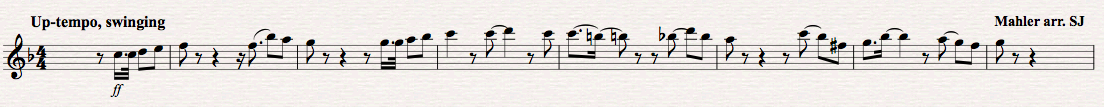

The big-band arrangement would also suit a turbo-charged

The big-band arrangement would also suit a turbo-charged