The grassroots ubiquity of spirit mediums (often female) in Chinese religious life is increasingly recognised (for collected posts, click here). I often plea for them to be recognised as among the most important practitioners “doing religion” in China—and now, as if in divine response to my entreaties, a welcome addition to our knowledge is

- Emily Ng, A time of lost gods: mediumship, madness, and the ghost after Mao (2020),

on spirit mediums in a county of central Henan province. [1] Here’s the blurb:

Traversing visible and invisible realms, A time of lost gods attends

to profound re-readings of politics, religion, and madness in the

cosmic accounts of spirit mediumship. Drawing on research across a

temple, a psychiatric unit, and the home altars of spirit mediums in a

rural county of China’s Central Plain, it asks: What ghostly forms

emerge after the death of Mao and the so-called end of history?

The story of religion in China since the market reforms of the late

1970s is often told through its destruction under Mao and relative

flourishing thereafter. Here, those who engage in mediumship offer a

different history of the present. They approach Mao’s reign not simply

as an earthly secular rule, but an exceptional interval of divine

sovereignty, after which the cosmos collapsed into chaos. Caught

between a fading era and an ever-receding horizon, those “left behind”

by labour outmigration refigure the evacuated hometown as an

ethical-spiritual centre to come, amidst a proliferation of

madness-inducing spirits. Following pronouncements of China’s rise,

and in the wake of what Chinese intellectuals termed semicolonialism,

the stories here tell of spirit mediums, patients, and psychiatrists

caught in a shared dilemma, in a time when gods have lost their way.

Ng begins by reflecting on her initial confrontational encounter with the medium Zheng Yulan, who soon moved from indifference towards her guest to rejecting any further engagement, a telling story that rings true—the perceived dangers of transmitting messages “across what the mediums deem enemy lines”. [2]

Henan [3]

Ng notes the “demonising” of Henan, in Ma Shuo’s term “a symbolic place of stagnation”:

Now, in place of a civilisational centre, Henan is more potent in the national imaginary as a land of poverty, backwardness, charlatans, and thieves, evocative of the famines of the 1940s and 1950s under Nationalist and Maoist rule, and of the HIV scandal of the 1990s, when villagers contracted the virus from blood plasma sales for cash.

Indeed, Henan suffered particularly grievously from the famine during the drive to communisation in the late 1950s. Citing Ann Anagnost on the “spectralisation of the rural” since the reform era, Ng evokes a society in which “ghostly presences swirl amid the hollow of an emptied centre”. See also Bards of Henan.

Mediums and vocabulary

Rather like Henan itself, mediums have been written out of the official history. They themselves have an alternative view of the Maoist and reform eras:

The purportedly antireligious campaigns of the socialist state, for the mediums, constitute cryptic acts of divine intervention—acts inaugurated by otherworldly forces that allowed the earthly state to misrecognise itself as secular.

Ng unpacks the local vocabulary for mediums and possession. The verb kan 看 is used, which she translates as “see”, as in kanxiangde 看香的 “one who sees incense”; as with the kanrizi “determining the date” among household Daoists, I’d suggest the more active rendition “looking with incense”, with the further implication of “taking care of through incense”. Mediums are also described as “those who walk/run/stand guard for spiritual power” (zougongde 走功的, paogongde 跑功的, shougongde 守功的). [4] Ng defines mediums broadly, as “those who regularly receive supplicants at an altar and those who regularly undergo possession at temples without necessarily receiving supplicants”, “lending their bodies” to spirits—as opposed to (usually male) diviners and fortune-tellers. Again like household Daoists, their domains are the yin and yang realms. The common term for the deities who possess mediums is xian 仙 “immortal”—who may also be ghosts.

Ng’s host quips with her by using the standard term shenpo 神婆 “witch”,

a term […] that I had brought to the scene, one intelligible to her while marking my externality to local articulations. It was a phrase more common with urban friends with less familiarity with such matters and carried a slight air of modern accusation. The term is rarely used in Hexian without either a note of disdain from those who denounce so-called superstitions or a knowing emphasis from those who do engage with such practices.

The aftermath of Maoism

Ng notes how the Cultural Revolution (and indeed, its first two years) often stands misleadingly as a condensed image of the Maoist era in its entirety. At a certain remove from Jing Jun’s study of the revival of a Confucian temple in Gansu, Ng approaches evocations of culture in a shifting moral landscape “not as a straightforward continuation but as painful enunciations and wounded reworkings after the cultural as such has been rendered petrified and petrifying”.

Despite variations on divine details, spirit mediums who frequented Fuxi temple in Hexian agreed: it was upon Chairman Mao’s death that the ghosts returned to haunt. Just across the road, in the psychiatric unit of the People’s Hospital, patients lament accursed lives, tracing etiological paths through tales of dispossession, kinship, and betrayal. South from the hospital, a Sinopec gas station sits atop what was once known as the “ten-thousand-man pit” (wanrenkeng), where bodies of the poor and treacherous were flung, throughout decades of famine and revolution.

Ng describes “a set of tensions, between a reconstituted rurality and an ambivalent urbanity, a mournful psychiatry and a shaken cosmology.” She evokes “culture as aftermath”: “the time when Chairman Mao reigned” (dangjia 当家, “in charge”, an ubiquitous term for both secular and sacred leaders, as we heard constantly in rural Hebei) is recalled as an interval of divine sovereignty, after which the cosmos collapsed into chaos.

Recognising a painful rupture to traditions of thought, in this sense, is not antithetical to taking seriously ongoing engagements with a cultural repertoire, as the cultural is loosened from assumptions of its qualities as an immobile, unbroken, closed system, and fragmentation is no longer assumed to be characteristic only of the modern or postmodern. Instead, attention to the aftermath of culture allows us to address how “culture” in the historical present is not simply an anachronistic concept but seethes in its simultaneous transmission of efficacious potential and tormenting attacks—from within and without.

At the temple square

Chapter 2 opens at the gate of the Fuxi temple in the county-town, as a man recites a Mao poem in a voice “from above”. For many mediums the journey consists in “walking Chairman Mao’s path”, and this is the focus of Ng’s study. But almost in passing she makes an important qualification:

Not all [mediums] centre their practices on Mao. They might be chosen by a number of tutelary deities from Buddhist, Daoist, and local pantheons to join their spiritual family and work in their service, or they might simply be vulnerable to possession by ghosts and spirits without an allocation of a divine task. But those who walk Chairman Mao’s path have a continual and notable presence at the temple square, on and beyond common ritual days, and even those who dedicate their ritual labour to other deities acknowledge Mao’s position in the cosmology.

So Ng surveys work on the Mao cult in the religious sphere—the study of Mao worship has become something of an industry (cf. this post on Gansu). As she notes, while commentators such as Geremie Barmé have described the “new Mao cult” as offering an implicit counterpoint to official portrayals, almost entirely divested of its original class, ethical, and political dimensions, her own work in Henan shows Mao still serving as ethopolitical and even cosmological figure.

In an inversion of the state’s ritual displacement of popular religion, the potency produced through Maoist-era political rituals is reactivated in post-Mao mediumship. Sharing a symbolic repertoire with the earthly state, the spectral polity speaks to the sense of a morally hollowed present and a revolution incomplete.

At the square she observes the scene acutely:

The air is dense with anticipation. Those who do not otherwise frequent the temple rush toward the gate, jostling their way through the crowds to burn the last batch of incense for the year. Making my way across the square, I am drawn toward a rumbling drum beat, steady and declarative, in sets of three. A large circle of onlookers gather around six women and two men, middle aged, as they prepare for ritual. They don matching and seemingly brand-new green Mao-era army coats, topped with brown Soviet-style fur hats, a single red star at the centre. One woman at the inner edge of the crowd holds a tall pole, topped with a large yellow flag with the word ling (lit. “command, order, or decree”; in this context meaning “divine command”) etched in red.

“Ayahao!” Another woman, in a red parka and a red embroidered dress reminiscent of old Shanghai, traces the edges of the encirclement with her steps, passing at its northernmost point. Facing the heavens, hands outstretched, her arms slowly lift toward the sky. She is receiving not only lingqi from above but also divine command for the opening of the ritual. “Ayahao!” she cries again—an interjection confirming an otherworldly presence or signal, often one’s own possession or infusion by spiritual personae or airs. “Ayahao! Ayahao! Ayahao!” echo several spectators in the crowd—a signal that they too acknowledge and experience the presence and signals of the spirits. While some rituals on the square involve particular appeals to the powers above, rituals such as this are often considered a mode of acknowledgement and oblation for the gods as well as a means of gathering spiritual force.

Inside the circle eighteen sheets of yellow fabric—used commonly in local rituals and often considered, on the temple square, the colour of the emperor—have been laid out in the shape of a fan, flanked by a head of cabbage and two large stalks of scallions. Agricultural goods are often incorporated into ritual spreads at the temple square, sealing within them symbolic meanings and forces both shared and esoteric. […] North of this more yellow fabric, this time in a row of five, every other sheet topped with a bamboo platter […] is covered by paper cutting of four concentric red stars, one embedded in another, the emblem of the Communist Party.

On the central bamboo platter, three cigarettes point northward, an offering to the gods, I am told. A common offering in Hexian in ritual and mediumship, cigarettes are often smoked by mediums and at times are burned in an upright position in place of or in conjunction with incense on the temple square. Some say the use of cigarettes was a carryover from the Cultural Revolution, when incense sales were banned and visits to mediums were held covertly behind closed doors in the night. Above the cigarettes four sticks of incense burn in a golden urn—three for humans, four for ghosts, as the saying went—aside a row of plastic-wrapped sausages, “because gods like to eat too”.

At the very top, farthest north, thus of highest position in the cosmic-symbolic geography, is a large poster of Mao in a red-collared shirt, seated and flanked by his generals in blue uniform. Placed on the poster are three mandarin oranges and three slices of metallic-gold ritual paper—two covered in looping spirit writing, the third with the words “Through virtue, one gains all under heaven” (de de tianxia).

Fifty or so onlookers have gathered around by now; men smoking, women bundled in scarves, several in their teens and twenties peering on, gawking, giggling. A man, perhaps in his late thirties, cigarette dangling from his lips, begins swinging a three-feet-long necklace of Buddhist beads above his head. After a minute or so, he meticulously lowers the necklace atop the poster of Mao and the generals. The two men in Maoist army coats begin striking a gong and cymbals, tracing deliberate steps across the spread of ritual offerings. Others—mostly those I have seen frequenting the square before—join to walk the perimeter of the encirclement, some singing, some dancing, some plucking offerings off the spread, brandishing them toward the heavens. The percussion gains speed. The cries intensify. “Ayahao! Ayahao! Ayahao!”A woman walks to the centre of the circle and closes her eyes. Another twirls, palms up highto collect spiritual airs from above. A voice bellows amid the drum and song.

“Wansui! Wansui! Mao zhuxi wansui!” Ten thousand years! Ten thousand years! Ten thousand years for Chairman Mao! A woman, standing beneath the yellow flag of divine command, howls at the top of her lungs. “Wansui! Wansui!” she calls out again and again, until her voice grows hoarse. In an adjacent ritual circle, the drumming also reaches its peak. “Shenglile! Victory! Dajia shenglile! Victory to all! Shijie dapingle! The world has reached supreme peace! Zhongguo shenglile! China has reached victory! “Wansui! Wansui! Wanwansuiiiii!” Ten thousand years! Ten thousand years! Tens of thousands of years!

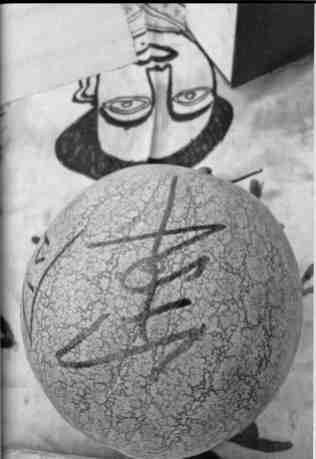

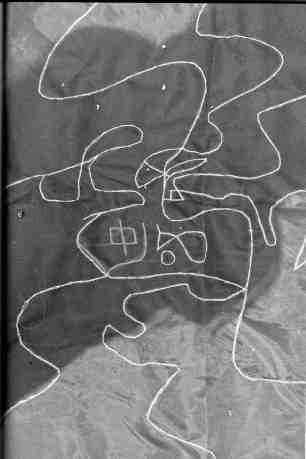

Probably out of discretion, the book only includes two photos:

Left: drawing of Mao on yellow fabric, with characters on watermelon reading junling “military [divine] command”. Right: “Cartography of loss”, showing stitching with neon yellow thread on red fabric, with character zhong “middle” in centre.

Ng points out that while corruption is a common lament, it is deeply embedded at all levels of society. She adduces the common issue of exorbitant entrance fees to temples (cf. Houshan). With the world of deities also tainted, the image of Chairman Mao has remained virtuous; many associate him, and the campaigns he led, with a kind of spiritual rectification.

In what is a widespread karmic trope, Ng notes that several Red Guards who took part in destroying the temple artefacts fell prey to strange illnesses or died bad deaths.

Acutely aware of fakery throughout reform-era society, local people struggle to distinguish fake mediums, and indeed fake deities who may possess them.

With the Chairman’s withdrawal back to the heavens postreform, an epidemic of brazen charlatanism and greed was unleashed across human and spiritual worlds.

So even if the “Mao shamans” are only one part of the picture, Ng contributes nuance to the discussion.

Consulting a medium at home

By contrast with the more performative public spectacle at the square, in Chapter 3, “Spectral collision”, Ng accompanies her host Cai Huiqing as she takes the bus to consult a medium at her village house, noting its unobtrusive “minimalist” nature, in Adam Yuet Chau’s term. As was common at the houses of mediums whom Ng visited, her altar had its own dedicated wing in the house complex, with its own entrance.

At the altar we take a seat across from Zheng Yulan on the west side of the square ritual table—the spiritually and symbolically less powerful side of the arrangement, in contrast to the east. In front of the altar, sitting between Zheng Yulan and us, is a large metal wash bin filled with incense from previous sessions. North of us all, thus at the top of the cosmic hierarchy, is the altar lined with several icons flanked by guardian lions, with Queen Mother of the West (Xiwang mu) at the centre. Cai Huiqing places a five renminbi note on the table as incense money (xiangqian)—a gesture that initiates the ritual exchange. *

* (Ng’s note:) In Hexian incense money is always laid on the table before a session begins. The amount given is usually volunteered rather than specified and often ranges from 10 to 50 renminbi at the village home altar session I saw. Compensation in gratitude for the completion of ritual assistance (huanyuan) is more likely to be specified and is higher than the initial incense money, ranging from the low to high hundreds of renminbi. More elaborate rituals or ones that require a medium to visit one’s home may reach into the thousands.

Zheng Yulan unwraps a a new batch of rusty-gold incense, lighting it slowly, attentively, squinting to determine whether the batch was properly lit before finally planting it into the large metal bin. […]

Zheng Yulan closes her eyes and begins yawning. In Hexian, as in many regions of China, yawning is a sign that the spirits had arrived and were entering the medium’s body, given the airy, pneumatic quality of other-worldly presences. “What is the name?” she asks.

Cai Huiqing responds with [her husband] Li Hanwei’s name, on whose behalf she is consulting the deities. As is often the case, the main supplicant of a session is not assumed to be the person who arrived at the altar; consultations are often initiated for others in the family. The reading of one’s own cosmic circumstances is not uncommonly left until last, after having inquired for others.

Zheng Yulan asks of Li Hanwei’s whereabouts. In an era of rural outmigration, family members are not always assumed to reside locally. Cai Huiqing replies that he is away, on the road, driving a large truck, delivering goods.

“Where does he drive?”

“From here to other counties, at times much farther, via the highway, to make deliveries.” Zheng Yulan contemplates this; then her right hand begins shaking as she whispers rapidly under her breath, conversing with her tutelary spirit. Another yawn hits her, and her eyes snap open. “He hit someone while he was driving.”

When it transpires that it was not a mortal but a xian ghost whom he had hit,

After enquiring about Li Hanwei’s local truck route, Zheng Yulan chuckles knowingly. “That corner—don’t you know it’s the ten-thousand-man pit, the wanrenkeng?” She is speaking of a major intersection, which for decades prior to the reform era was known locally as the site of a mass grave. During the famines of the 1940s and 1950s, it is said that those who simply collapsed of cold and hunger and died in the street or those whose families did not have the land to bury them in were simply tossed into the pit. Later, during the Cultural Revolution, it also served as resting place to those accused of political dissent—they were killed point-blank at the edge, I was told.

Now the ten-thousand-man pit lies beneath a Sinopec gas station. It is no longer so actively feared as it once was yet still houses countless hungry, wandering ghosts from decades past. […]

The ten-thousand-man pit is but one among many sites for spectral collisions in Hexian. Ghosts are also said to be common at intersections where their souls had been released during mortuary ritual; their personal gravesites; homes of women who recently miscarried; sites of past wrongs, reminiscences, and ghostly sociality […]; and simply arbitrary places along their driftings.

Ng goes on to illustrate such collisions through the history of the ten-thousand-man pit, and the famine of the 1940s and 50s. While she mentions in passing the terrible famine that followed the 1958 Great Leap Backward, I wonder if this is also a common theme of spectral encounters; rather,

in Hexian recollections of the pre-Maoist Old Society, transmitted through oral accounts and corroborated in national media, together with the sense of precarity and moral collapse in the post-Mao present, heightened the sense of safety and exceptionality of Maoist times.

As the consultation continues, Cai Huiqing rushes to the kneeling mat south of the altar and begins to kowtow northward, but the gesture seems insufficient. “Seeing with incense”, the medium gives a spoken exegesis, instructing Cai to burn six hundred ingots folded from gold spirit money to placate the ghost and ten reams of yellow spirit money to show gratitude to the deities. She correctly foretells that her client will have revealing dreams, which she describes on their next visit some days later. As Zheng Yulan requests clarifications, she concludes that a ghost is trapped and choked beneath “ a certain arc-shaped object, stuck beneath Cai Huiqing’s home, in the southwest corner”.

On her return, Cai indeed excavates an old, rusted pipe clamp from her yard, which she must get rid of. Such concealed artefacts may indeed be deemed malignant: in my book on a Hebei village I noted a story of villagers consulting a medium to locate a trowel accidentally buried in a wall as they were building a house.

Even if her husband and children disparage her recourse to mediums as a superstitious squandering of time and money, Cai Huiqing regards it as a way of mitigating danger for her family.

Ng notes that such spectral collisions may overlap with the potential natal calamity of one’s horoscope.

Source here; cf. brief video clips online.

On the psychiatric ward

With striking, cinematic abruptness, Chapter 4, “A soul adrift”, transports us to the psychiatric unit of the county People’s Hospital, which indeed is across the road from the Fuxi temple—there’s even an advertisement for it on the big screen in the temple square.

In a highly original and insightful juxtaposition, Ng spends time with several patients whose crises seem to call for such a modern form of intervention, considering medical anthropology, madness, and the divided self, and again drawing on much research. She had already worked among psychiatric patients in Shenzhen, where she found that “the post-Mao generation increasingly individualised and psychologised their illness, with a heavy sense of self-blame, in contrast to the political, sociomoral, and situational accounts from those who came of age in the Maoist era”. Indeed, this perspective first came to my attention with an article on psychiatric patients in Hebei (n.2 here).

Ng also refers to Arthur Kleinman’s study of neurasthenia, which he found to provide a somatised, medically legitimised, and politically tolerable idiom through which to articulate otherwise punishable laments during the Cultural Revolution.

Many of the problems that people experienced stemmed from the pressures created since 2005 by the state’s New Socialist Countryside project (the object of several trenchant critiques by fine scholars such as Guo Yuhua)—people’s precarious economic prospects associated with migration and return, and familial tensions. At the same time,

many patients and families speak of the illness for which they come to seek treatment in terms of possession, soul loss, and ghost encounters or as the blurred boundary between madness and otherworldly happenings.

For some, social disintegration and crisis in filial relations are a manifestation of cosmic chaos.

The hospital might serve, modestly, as a “tentative site of retreat” from such pressures.

Save weddings, birth celebrations, and funerals, hospitalisation—psychiatric or otherwise—seems to be one of the few occasions in Hexian that draws local extended family and immediate family near and far, along with select friends and neighbours, into a circuit of visitations.

Ng meets a withdrawn, wandering mother, whose few utterances often reference the commune era; her crises have not been mediated by spirit mediums. Her worried daughters take turns attending to her, returning from Beijing.

Next Ng meets a female student, disturbed by the pressures of education and her impasse with her migrant father, who only thinks about money yet whom she describes critically as an “honest” (laoshi 老实) type. She reflects well on that common yet ambivalent term:

Until the early 1980s honesty connoted a good person, hardworking and trustworthy, the ideal marriage partner, particularly when describing men. With the turn toward market competition and growing disparity in the reform era, the same term began morphing in connotation, pointing to a naÏveté vulnerable to exploitation and duping, which would not fare well in the new moment and risks falling short of supporting a family amid the social games of the privatised world. Honesty also came to mark a caricature of the rural, of peasants too simpleminded for complicated times. As Yunxiang Yan writes of young women he encountered in rural Heilongjiang in the 1990s, “a number of them maintained that that [honest] young men had difficulty expressing themselves emotionally, and lacked attractive manners”. By contrast, articulate speech, emotional expression, ambition, and a capacity for advancing one’s social and economic position had come to be valued, reversing the previous connotations of similar traits as unsavoury signs of empty words, lasciviousness, and aggression.

I’m sure this is right, though I haven’t picked up so much on it. Often when I’ve heard the term used, I’ve felt that it was not only an implied rebuke to the widespread current avarice and duplicity, but also a tribute to those who had managed to maintain a moral core under Maoism, resisting fickle political pressures—like the much-admired Li Jin in Yanggao.

The patient’s mother has visited various “superstitious” guides on her behalf, both mediums and fortune tellers—“those who ask for directions for you” (gei ni wenwenlu nazhong, another formulation likely to serve fieldworkers better than alien, judgmental terms like shenpo “witch”). Like Ng’s host, the mother engages with the spirit world on behalf of her kin, “in search of otherworldly forces shaping the predicaments of the present”. While the student herself seems indifferent to all this, she doesn’t think the various drugs she has been prescribed (olanzapine, alprazolam, paroxetine) will suffice to help her, though she feels comforted by the IV drip. She places greater faith in counselling, but it’s available only in the major cities.

Next comes an injured former miner diagnosed with acute psychosis. Ng gains background from his wife. His frustration at his loss of earning power and, again, tensions with his father clearly play a role in his disorder. A female relative had consulted a medium on his behalf, who again diagnosed a spectral collision, but a “soul-calling” session was unsuccessful.

Here Ng reflects on what Yan Yunxiang described as the crisis of filial piety, “a deep shift in notions of intergenerational reciprocity”.

Across my conversations with patients and families, the language of psychiatry is present but, to some extent, sidelined. For most the psychiatric ward is one stop in a broader search for healing, and psychopharmaceutical cures are one hope among many.

Chapter 5 goes on to describe another patient, Xu Liying, herself a medium “summoned to the revolution” eighteen years previously by a vision of Chairman Mao and the Ten Great Marshals, struggling against evil spirits—a mission that torments her.

Brought to the ward by her husband and son, she is the only patient there diagnosed with “culture-bound syndrome”, but remains devoted to her divine task. Several fellow mediums come to visit her, trying in vain to convince the doctors to release her so that she can continue her work.

Again, much of Xu Liying’s task consists in discriminating fakery and corruption. Her cosmos depends heavily on the ledgers of the courts of hell. Among her few trusted deities is none other than the Eternal Mother (Wusheng laomu), the central figure of “White Lotus” eschatology. For her and other mediums in Hexian,

the historical arrival of Mao is at times linked with the arrival of the Maitreya Buddha, in a moment when China had reached the brink of ruin and calamity.

Ng notes that

The spatial face-off of the temple and the hospital follows a series of encounters between health and religiosity throughout the 20th century.

She makes another important qualification:

To be sure, psychiatry and mediumship do not always overlap in Hexian. Plenty of those in Hexian who have experienced possession by deities or ghosts do not wind up at the psychiatric ward, and many at the ward do not describe their ailment in terms of the invisible yin world. At the same time languages of madness pervade contemporary mediumship, and talk of possession is very much familiar to psychiatrists and patients at the ward.

In the Coda Ng observes

The mediums, having been written out of modern religious and medical legitimacy, continue to address madness in their consultations and ritual repertoires. Symptoms, for the mediums, are not merely representations of biological truth or psychiatric reason but signs of cosmopolitical disarray. Possessed bodies and disturbed dreams link the present with its hauntings, reinvesting the most local of geographies with significance across national, world-historical, and cosmic scales.

The mediums of China today are not those of the imagined past.

* * *

Now I’d like to read more about other local temples, further sessions, the role of gender (Ng notes that more women than men become mediums, but doesn’t go into detail), economic aspects, and the part mediums may play in any sectarian activity. I also find Xiao Mei’s diary of a busy medium in Guangxi makes an instructive template. Mediums have domestic altars, but Ng doesn’t mention any painted pantheons such as we find in parts of Shanxi and Shaanbei. As to performance, her comments don’t go much beyond “the song and drums reverberating from the proliferation of ritual across the temple square”. I wonder if the Hexian mediums perform group sessions in domestic settings as well as in the temple square. In some regions (such as Yanggao), they may speak and sing in dialects of which they have no knowledge in their mundane life.

Mediums at temple fair, Yanggao 2011. My photo.

Ng does both descriptive ethnographic detail and broader theory very well, but I often found the former getting buried beneath her impressive array of theoretical citations and reflections. We can always consult Foucault and Derrida, but the grassroots detail of ritual life in rural China need to be evoked. Since Ng met many mediums, I kept wanting more thick descriptions of what they actually do.

It’s often a challenge to balance ethnography and theory, but to my taste I’d sacrifice some of the latter for more of the former. Still, A time of lost gods is a most original portrait of an important topic, sympathetic and non-judgmental.

[1] Ng uses pseudonyms both for the location and for personal names.

[2] For Navajo ceremonies for protection against baleful ghosts amidst modern traumas, see here—including Barre Toelken’s cautionary tales (n.5 there), evoking Ng’s initial encounter in Henan.

[3] For Henan, Peter Seybolt, Throwing the emperor from his horse (1996), a biography of a village leader through three eras, remains useful. Note also sectarian groups such as Eastern Lightning (see e.g. Ian Johnson, The souls of China, chapter 25). I really should get a grasp on ritual life and expressive culture in Henan—perhaps setting forth from the relevant volumes of the Anthology.

[4] Among many local terms for mediums, see e.g. Hebei, Shaanbei, and south Jiangsu. For educated and local vocabularies more generally, click here.

As Nettl went on to observe, the very

As Nettl went on to observe, the very

Transcriptions may look forbidding to the outsider, but audio samples of such songs might be a good test for scholars who disclaim musical expertise: they too should be able to make such simple and useful observations.

Transcriptions may look forbidding to the outsider, but audio samples of such songs might be a good test for scholars who disclaim musical expertise: they too should be able to make such simple and useful observations.

The wise, principled

The wise, principled

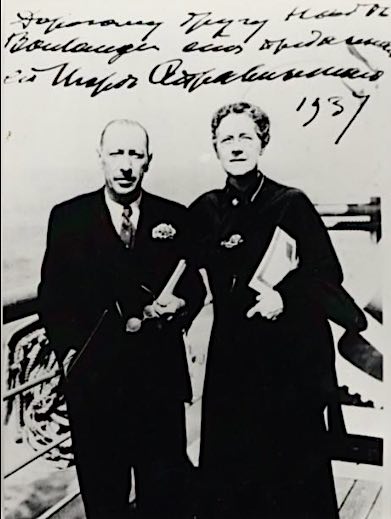

In 1983 I organised a visit to London by the great art historian and Chinese furniture scholar Wang Shixiang 王世襄 (1914–2009); I had translated a piece by him. and we had first met in Beijing in the early 1980s. The trip was done on a shoestring, and it pains me to think how spartan was the Imperial College London student hostel I booked him into, though he would never have complained—he had after all done years and years in cadre school. One of the grandest of London’s dealers in Chinese art took us to a posh lunch; it was a measure of Mr Wang’s cosmopolitan youth that he ordered cheese for afters. He ate half, and asked the waiter to wrap the rest (presumably for his breakfast, which I had not provided). As the beginnings of a sneer formed on the waiter’s face, it being that kind of restaurant, one of the grandest of London’s dealers in Chinese art gave him a very ferocious look that eloquently said, “This gentleman is my guest. I eat here often. Wrap his cheese”.

In 1983 I organised a visit to London by the great art historian and Chinese furniture scholar Wang Shixiang 王世襄 (1914–2009); I had translated a piece by him. and we had first met in Beijing in the early 1980s. The trip was done on a shoestring, and it pains me to think how spartan was the Imperial College London student hostel I booked him into, though he would never have complained—he had after all done years and years in cadre school. One of the grandest of London’s dealers in Chinese art took us to a posh lunch; it was a measure of Mr Wang’s cosmopolitan youth that he ordered cheese for afters. He ate half, and asked the waiter to wrap the rest (presumably for his breakfast, which I had not provided). As the beginnings of a sneer formed on the waiter’s face, it being that kind of restaurant, one of the grandest of London’s dealers in Chinese art gave him a very ferocious look that eloquently said, “This gentleman is my guest. I eat here often. Wrap his cheese”.