It’s worth rounding off these vignettes of the Li family on tour with some of my daily notes, as a little contribution to the ethnography of one, um, caravanserai on the global bazaar—and also as a further illustration that Daoists are Real People, not mere Faceless Paragons of Ancient Wisdom.

18th May

After a long journey from Yanggao via Beijing, the Daoists reach our hotel at 7.30am. Alas, despite my blandishments at the desk, they have to wait all morning for their rooms to become available, but I catch up with them as they rest on sofas in the foyer, letting Li Manshan sleep in my little room.

I take Li Bin, Golden Noble, Erqing, and Wang Ding round the corner to Rue de Rome, helping spendthrift Li Bin buy a preliminary round of gifts for his guanxi network back home: he asks me to help him choose four bottles of olive oil and ten bottles of vin rouge. Confessing my ignorance, I try to muster a little bon goût. He wants to splash out on more posh bottles, but I choose vin pretty ordinaire, trying vainly to control his reckless spending. A friend of Erqing has even asked him to buy him a particular vintage of Château Lafite. I tell him to forget it. Still, imagine—twenty years ago the average annual income for a Yanggao peasant was still only around £100.

We do splash out on an adapter, though. This has become a touring ritual, since they never bring the ones we have bought on previous trips. They keep it busy with recharging their mobiles and i-pods.

At midday we go round the corner to Rue Budapest for Sichuan noodles. They drink Erguotou liquor. We chuckle over our Confucian hosts’ quirky arrangement over expenses: 20 kuai each per meal for them, a mere 15 kuai for me. This causes much mirth: do I get less because I’m too fat?! After lunch, and after a meeting with Teacher Wang, now abbreviated to “hold meeting” (kaihui), their rooms are available—three doubles (sociable types that they are, they wouldn’t even want singles).

It’s so great to be on tour with a brilliant sextet who have been doing rituals together for thirty years, and who are now in the rhythm of touring abroad too. Li Manshan is a wise laissez-faire (wuwei?!) leader, Li Bin an able fixer, Golden Noble and Wu Mei best mates, and Erqing and Wang Ding are cool too. We slot into our secret language, always laughing, dusting off old stories, devising new takes.

At 6pm our hosts Adeline Herrou and Yan Lu, with her assistant Alessandra, come to our hotel to guide us to the conference banquet. Arriving a bit late in a downpour, we are fortunately siphoned off to another quieter restaurant nearby so we can get to know our hosts in peace. Yan Lu is géniale, petite, full of joi de vivre. We give her our favourite ritual couplet written by Li Manshan, and local dried apricots from Yanggao. It’s been a long first day (and their travel from Yanggao itself took nearly 24 hours before that), but after taking the metro home, Li Manshan and I have our usual sweet chat outside the hotel.

19th May

We have a good breakfast; they eat plenty of everything, with lashings of coffee. I no longer have to help—they’re even experts with the egg-boiling contraption.

I end up in Golden Noble and Wu Mei’s room, where we have a nice chat. I mention the Wang family Daoists of Shuozhou just southwest of Yanggao. Wu Mei knows Wang Junxi’s guanzi-playing and likes it, having seen his videos online; he has appeared in a secular show with them, but there was nothing much for them to talk about!

Now that my film and book are out, we can relax without my constant pedantic questions. But I’m always in fieldwork mode—I just can’t help taking notes. Li Manshan tells me more about the Temple of the God Palace in the southeast of his village—site of the original settlement Dazhaizhai 大寨寨.

Relaxing in the scripture hall between rituals, Golden Noble and Wu Mei amused by my notebook, 2011.

The Daoists busy themselves preparing for our first gig at the Nanterre conference: while Li Bin packs all the stuff to take, Golden Noble checks their sheng mouth-organs, Wu Mei works on his reeds. Their rooms are scattered with the debris of touring: shavers, battery chargers, mobiles, i-pods, cymbals, a solder (to tune their sheng), fags, pot noodles just in case, cigarette cartons, gifts of dried apricots…

We take the train to Nanterre, and after a canteen lunch the splendid Hélène Bloch takes us on a reccy of our pre-concert route to and through La ferme du bonheur circus on campus—it’s just like being back in Yanggao, as it really is a farm, with sheep, a peacock, and lovely laidback warm people. I dream of running away to join the circus; there’s a new release of La strada just out. The peacock displays for Li Manshan but not for me, a typical show of xenophilia (chongyang meiwai 崇洋媚外)!

La ferme du bonheur. Photo: Hélène Bloch.

After my film screening, the Daoists are waiting outside to lead the audience through the campus to the farm, where we all take a tea-break, and then to the concert hall.

The hall is small, but the gig is amazing, as always. Our encore of the Mantra to the Three Generations, with me joining in, goes well.

As Ian Johnson observes in his book The souls of China (pp.37–40), the progression of the Li band to minor international celebrity has been a gradual process, from Chen Kexiu’s research to the 1990 Beijing festival, through to our foreign tours (cf. my book, ch.18).

For what it’s worth, such northern ritual styles do perhaps lend themselves better to the concert format than many southern Daoist groups, the entrancing wind ensemble supplementing the vocal liturgy and percussion.

We take the train back to our hotel, then go for supper. Li Manshan has given me two bottles of lethal Fenjiu white spirit from Shanxi, which we (all except him—he’s not a drinker) polish off with our meal. I’m TP again. I stagger back to my room to take stock, then around midnight Li Manshan knocks on my door for another “meeting” outside. First we gravitate to my bathroom for me to explain how the taps work, and he tells me his story about a Chinese guy who brought back the hotel soap as a present, and his mate says “Uurgh, this foreign white chocolate tastes disgusting!”.

We adjourn outside for more jokes, and fond reminiscences of Li Qing. As always, our most intimate moments are late at night, tranquil, alone together. These tours just get better and better. Yan Lu and all our hosts love this, and so do we.

My two rules for when the time has come to leave China:

1) when I begin to enjoy drinking baijiu white spirit;

2) when I begin to like Chinese pop.

In the old days such tours were inevitably accompanied by a gaggle of superfluous apparatchiks on a freebie trip abroad. Now the Daoists have their own private passports, and on tour I look after them on my own.

It’s also amazing how much Chinese food abroad has improved over the last couple of decades. “Long gone are the days when” we have to endure sweet-and-sour pork—though even that has a certain nostalgia for me. With a busy schedule, and several good Chinese restaurants on our doorstep, I feel no great need to educate the Daoists in the richesses of French cuisine.

20th May Saturday

By 5am I’m chatting with Li Manshan again outside the hotel over a fag. After a quick breakfast we all take the new line 14 to Gare de Lyon. Streetwise Erqing is useful on the metro, noticing our route, watching out for signs—I no longer need to marshall them so closely, but the spectre of losing a national treasure in New York in 2009 still haunts me.

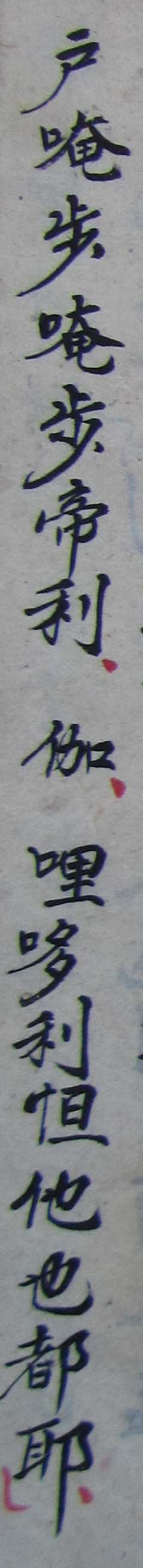

We’re in plenty of time for the 8.59 to Clermont-Ferrand—whose Chinese name Kelaimeng Feilang, preceded by Aofonie (Auvergne) reminds me of one of the Li band’s pseudo-Sanskrit codas, such as the one at the end of the hymn Diverse and Nameless!

We’re in plenty of time for the 8.59 to Clermont-Ferrand—whose Chinese name Kelaimeng Feilang, preceded by Aofonie (Auvergne) reminds me of one of the Li band’s pseudo-Sanskrit codas, such as the one at the end of the hymn Diverse and Nameless!

I go off with Li Bin to buy lunch for the band to eat on the train.

The lunch-pack of Notre Dame

(How could I resist? Just in case you’re not familiar with this one, it’s the answer to “What’s wrapped in cellophane and goes DONG?”)

Wu Mei and Li Manshan soon nod off, the latter tapping out drum rhythms even in his sleep. Later as I try to photo him chatting with Golden Noble, he tries to mess up my photo with his smelly sock.

They get excited seeing a field. To me it’s just a field. Wisely, they’ve long given up asking me technical questions about European agriculture. Golden Noble and Wu Mei have a beautiful chat—relaxed, thoughtful.

Our train is late, but hey. Valérie Bey-Smith and Wu Yunfeng, our keen Confucian hosts, meet us on the platform. Clermont-Ferrand feels pleasantly remote and eccentric—a bit like one of those Hunan mountain towns (where I’ve never been, BTW). We make hasty preparations for the gig in the conservatoire. After intros from the Confucius Institute and the Chinese consul in Lyon, my talk goes fine, with Valérie translating for me. I’m getting better at this. The gig is great—the audience goes wild.

The concerts only last an hour, but the Daoists are soaked in sweat. Still, it’s no big deal compared to their long rituals in Yanggao. The two sheng players, little trumpeted, have to work especially hard. In the trick sequence, even the way Erqing stays still for Wu Mei to slot the bell of his curved trumpet onto the pipe and then at once starts twirling it, playing all the while, is virtuosic. Wu Mei sometimes gets in a bit of trouble balancing the cymbal on his head, or the false eyes (walnut shells) coming loose, which all adds to the excitement—I observe to him that such little hitches should be a deliberate part of his routine, so as to show the audience how difficult it is, and keep them on edge.

Nanterre. Photo: Nathalie Béchet.

Congratulations from the Chinese Consulate General in Lyon.

I get the usual erroneous compliments from the Chinese about me “discovering” them, and about the Chinese not knowing their own culture. OK, urban educated Chinese may not (I’m no great authority on Morris dancing either), but there has long been a wealth of research from native scholars, which is ongoing; and The Plain People of Yanggao have always been perfectly clear about their local Daoist culture.

After a nice meal with our hosts and innocent young students, they take us for a little tour of town, but we’re all completely knackered, and soon retire to our quaint hotel—next to the Hotel Ravel, I note.

Valérie, like our other hosts, is understandably ému (not Emu, or Rod Hull).

21st May Sunday

Up again by 5, I take a little stroll near our hotel with the band, admiring the market, and the murals on the wall next door.

In a nearby square we find five little posts, correctly arranged for a bonsai Hoisting the Pennant ritual (my film, from 44.21) on a future fantasy visit of Li Manshan’s 5-year-old grandson and his schoolmates.

Doing daily travel with a gig is tough—but like my former orchestral life, it incites camaraderie. Our previous tours have been less frantic, but this one is pleasantly condensed.

The touring life. Photo: Wu Yunfeng.

Valérie and Teacher Wu take us to the station, with thoughtful gifts of Gitanes (!) and food for the train. We were also happy to receive Clermont-Ferrand Confucius Institute umbrellas.

Valérie sees us off on the train.

The train ride is fun again. It’s much faster today, so we arrive early at midday, and take the metro to find the Centre Mandapa, a splendid venue for world music since 1978, led by the splendid Milena Salvini.

With Mandapa technician Milou we try out my film for a most successful screening; my intro goes well, and at the end Li Manshan and I take a bow. The Daoists love watching our film too.

It’s a lovely little area, so we have plenty of time to relax. They find the quirky antique emporium over the road. A succession of beggars ask us for fags, which they give gladly. Intriguingly, the Centre Mandapa is also right opposite the 1913 church of the Antoinist cult:

The state stance on “heterodox cults”? My photo.

We set up the stage during a tea-break for the audience, then the Daoists do yet another amazing gig. Though it’s a small room, my fears that the concert will be deafening turn out to be unjustified—it’s a great acoustic. I join them again for the encore (playlist #3, with commentary here).

It’s always good to see friends at our concerts. Several Shanxi people introduce themselves, excited to find the band performing in France; and today fine scholars like Jacques Pimpaneau, Robin Ruizendaal, François Picard, and Nicolas Prevot come along too.

One cultural difference: after a gig, sure we all want to get away, but the Daoists only drink with food, not before or after (usually), whereas we WAM musos make a beeline for the pub as soon as we have taken our final bow.

Our secret language (“black talk” heihua) is as arcane as ever, with all our inside jokes. Recalling a filthy joke that Guicheng told at a hotel party in Leipzig (I can’t possibly tell you that one), I only have to say “Can you sew this up for me?” for Li Bin to burst out laughing. We giggle again at Tian Qing’s “Eat a young monk” joke.

22nd May

We have a free day at last before the Daoists’ evening flight home. Last night Old Lord Li had a bath, slept till 1am, watched TV, slept again, and got a call from a family in Pansi village to determine the date for a funeral, so he was up before 4. Meeting up at 5 yet again, I take him to the bar down the road, where Tweety McTangerine comes on TV—Li Manshan hasn’t even heard of him, how enviable! Back to my room together to read Yan Lu’s draft article on the Nanterre events.

Li Manshan calls the Pansi family again at 6am. It’s a village that he likes best, and they most trust him. Then we have a good breakfast.

We stroll down together past the Opéra to the amazing Chinese department of Galeries Lafayette, brilliantly rendered as Laofoye (“Old Buddha Elder”). Li Bin and Erqing buy loads of perfume (“Hey guys, how many lovers have you got?!”)

Later Li Manshan and I buy toys for his young grandson: a trumpet and maracas, to go with the, um, Ming-dynasty instruments I bought him before.

We store our luggage and go for lunch, washed down by Leffe. Old Lord Li is drumming with his chopsticks again. Delightful mood over lunch, as always—everyone chipping in with stories, jokes, reflections. Over delicious yuxiang qiezi, I ask Li Manshan if he has an aubergine tree. Often the subject turns to their hymns, as well as the Zouma suite (playlist #4, commentary here) and funky Yellow Dragon percussion piece, and the whole calibration of the trick sequence—how to improve them, tempi, and so on.

They rest on sofas at the hotel, and I film Li Manshan telling another sh-sh-sh-shikuaiqian joke.

Later we take line 14 to Châtelet, and wander round the little islands. I choose different flavours of Bertillon ice-cream on Île de la Cité for them. After a little guided tour of Notre Dame, we return home for a quick supper of noodles and beer before Adeline and Yan Lu arrive, Lu thoughtfully giving them posh French chocolates. I have to go off to catch the last train back to London, but their taxi for the airport arrives early, so I can wave them off after all, but it’s a hasty parting.

If it’s a quick hop back home to London for me, their journey was not so simple:

22nd: 23.20 flight from CDG to Beijing,

23rd: landing at 15.20, 21.40 train from Beijing station,

24th: arriving in Yanggao at 03.44! But both Li Manshan and Li Bin had to rush off almost immediately to attend to village clients (for Li Bin’s diary after returning, see here).

I’ve been out of love with Paris for a while; the romantic image is hard to square with its gritty realities (rather like China, perhaps?). But this trip with the Li band naturally made me fall in love with it again. In this supposedly homogenised age—as with other cities like Leipzig, Venice, Seville, or Lisbon—we must delight in Parisian culture too!

After Daoist music in France (and Italy, and Germany), try Andean music in Japan…

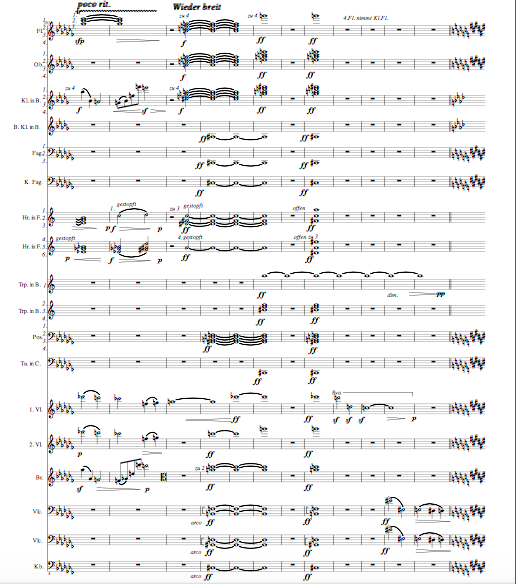

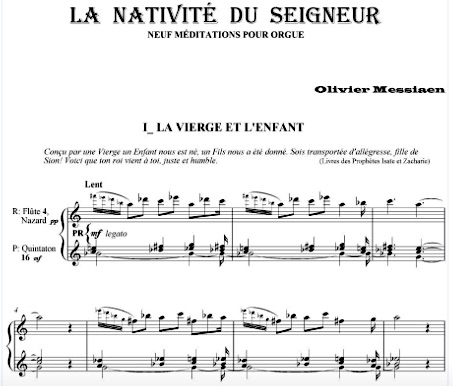

As I write these notes up, Haitink conducting Mahler 9 comes on Radio 3, live from the Barbican; and then next evening, another live broadcast of Turangalîla! Perfect. I hear echoes of the Li family rituals in both: all the contrasts of monumental tutti and intimate chamber styles that we find in a Daoist ritual. But that’s just me… If only Messaien were still around to hear the Li family in Paris!

Posted at 5am to commemorate daily sessions with Old Lord Li.

Baseball with Lenny, Japan 1970.

Baseball with Lenny, Japan 1970.

*

*