Still giggling at Stella’s resumé of The Flayed, I must just return to celebrating the original Cold comfort farm.

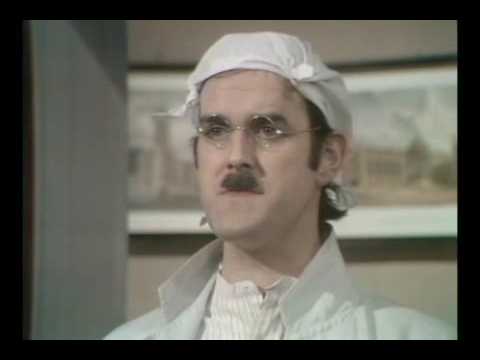

You might think it would be one of those books that could only be spoilt by being Made Flesh (or at least celluloid, or whatever they use these days, with their new-fangled ungodly ways). But the 1995 TV film is highly regarded, and at a tender age, having recently read the book, I found the 1968 serialization most drôle—such as Alastair Sim as Amos, perfect:

“Ye know, doan’t ye, what it feels like when ye burn yer hand in takin’ a cake out of the oven or wi’a match when ye’re lightin’ one of they godless cigarettes? Ay. It stings wi’ a fearful pain, doan’t it? And ye run away to clap a bit o’ butter on it to take the pain away. Ah, but” (an impressive pause) “there’ll be no butter in hell!”

Then there’s the herd of Jersey cows—Graceless, Aimless, Feckless, and Pointless; and Aunt Ada Doom’s regular use of the dilapidated Milk Producers’ Weekly Bulletin and Cowkeepers’ Guide to smite anyone within reach.

The book also exemplifies the clash of urban and rural cultures that is a major theme of anthropology, not least for China. The Li family Daoists sum it up brilliantly in their joke after the final credits of my film.

Flora takes on the project of Meriam the hired wench, in labour yet again:

And carefully, in cool phrases, Flora explained exactly to Meriam how to forestall the disastrous effect of too much sukebind and too many long summer evenings upon the female system.

Meriam listened, with eyes widening and widening.

“ ‘Tes wickedness! ‘Tes flying in the face of nature!” she burst out fearfully at last.

“Nonsense!” said Flora. “Nature is all very well in her place, but she must not be allowed to make things untidy.”

Meriam’s mother (wife of Agony Beetle, no less) has a plan for her daughter’s growing brood:

“Come another four years and I can begin makin’ use of them.”

“How?” asked Flora. […]

“Train the four of them up into one of them jazz-bands. […] So that’s why I’m bringing them up right, on plenty of milk, and seein’ they get to bed early. They’ll need all their strength if they ‘ave to sit up till the cows come ‘ome playing in them night-clubs.”

Lastly, statuesque sullen ravaged Judith:

I am a used husk… a rind… a skin.

Fragrant Flora’s own personal bible, The Higher common sense by the Abbé Fausse-Maigre, isn’t always up to the challenge posed by the Starkadders. (BTW, one wonders if the Abbé lived at 7 bis, rue du Nadir-aux-Pommes.)

Judith gives a classic rebuke to Flora’s gentle probing:

“By the way, I adore my bedroom, but do you think I could have the curtains washed? I believe they are red; and I should so like to make sure.”

Judith had sunk into a reverie.

“Curtains?” she asked, vacantly, lifting her magnificent head. “Child, child, it is many years since such trifles broke across the web of my solitude.”