This discussion of the Dispatching the Pardon (fangshe 放赦) ritual sets forth from my Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.246–50, exploring the imperfect match between Daoism as performed and as shown in ritual manuals.

The highlight of my first visit to Yanggao in March 1991 was witnessing the great Li Qing presiding over a funeral at Greater Antan (see my film, from 48.35). I didn’t know how lucky I was. It was as if a Martian happened to land on earth, not at a conference of middle managers in Belgium, nor even at a church fête in Suffolk—but in Leipzig in 1727, filming the premiere of the Matthew Passion on her 3D eye-laser system, and then assuming that this was typical of life on Planet Earth. And then recording an episode of Family Guy over it.

The Pardon ritual was traditionally performed for both funerals and temple fairs, with the words “filial sons” (xiaozi) or “filial kin” (xiaojuan) as alternatives for “master of the retreat” (zhaizhu) or “temple chief” (miaozhu).

For funerals the Pardon is normally only part of the three-day sequence; the 1991 funeral was held over only two days, but Li Qing performed the Pardon at the request of the son of the deceased, a gujiang shawm player who loved the ritual for its lively (honghuo) atmosphere.

Li Qing’s band that day included his senior colleagues Li Yuanmao and Yuan Lishan; the guanzi player for the jocular “catching the tiger” sequence was Wang Chang, from the related Wang family in Baideng township. Li Qing’s son Li Manshan was taking part on drum, and the young Wu Mei was there; the band also featured Li Peisen’s second son Li Hua, as well as Li Yushan, son of Li Peisen’s older son.

As Li Manshan later recalled, this was the third time he had taken part in the ritual; they performed it for the 1987 video project, and did it again around 1993 for a funeral in Wangjiatun. The younger recruits Li Bin and Golden Noble have performed it for temple fairs, but by 2015 they hadn’t done it for nearly ten years—like Crossing the Bridges, kin and villagers now consider it “too much hassle”. It hasn’t been used for temple fairs since the early 1950s.

The Pardon manual

The Li family Daoists distinguish between the routinely used “inner five rituals”, and the optional “outer five rituals” (see Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.30–32). Before Liberation Li Peisen copied a lengthy manual including the latter, generously titled

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

Numinous Treasure [Manual] for Opening the Quarters, Summons, Reporting, Offering Viands, Roaming the Lotuses, Smashing the Hells, Dispatching the Pardon, Crossing the Bridges, Precautions against Hailstones, and Averting Plagues of Locusts.

There was little trace of these “outer” rituals in their practice after the 1980s’ revival.

Finding Li Qing consulting Li Peisen’s early manuscript at the 1991 funeral, I hastily took some photos, rather randomly; by 2011 Li Manshan could no longer find it, so we rely on the faithful copy that Li Qing made in the early 1980s, divided into two volumes, with 42 double pages in all.

The Pardon itself takes up fifteen double pages. It’s one of their most complex, opening with long sequences of zhenyan mantras in four-, five-, and seven-word structures, and containing elaborate fu 符 talismans and jian 简 slips. Whereas most funeral segments are now dominated by the Heavenly Worthy of Grand Unity who Rescues from Suffering (Taiyi jiuku tianzun), this ritual is addressed to the Jade Emperor, in his role as Heavenly Worthy Who Pardons Sins (Yuhuang shezui tianzun). The talismans are addressed to the Three Officers (sanguan). The 108 pardon slips (shetiao, shewen) to be recited are combined into a few long documents.

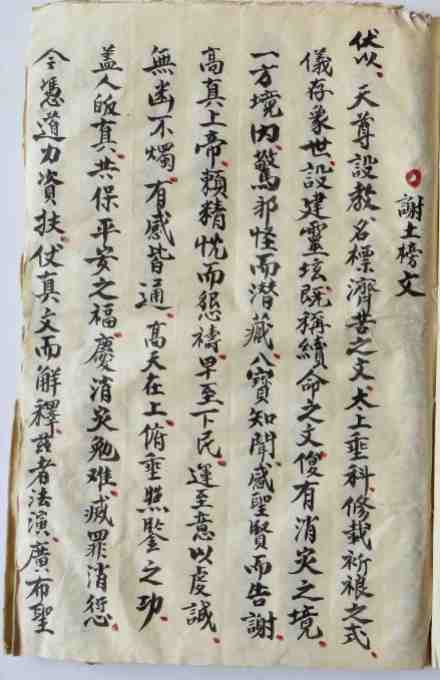

Some pages from Li Peisen’s copy:

Slips to Rescue from Suffering.

Recto: slip for Long Life.

Verso: in the last line, the term jiao (Offering) in “dark yang pure jiao”

(mingyang jingjiao 冥陽凈醮) refers to a funeral;

the listing of “Shanxi Datong fu” shows its local origins.

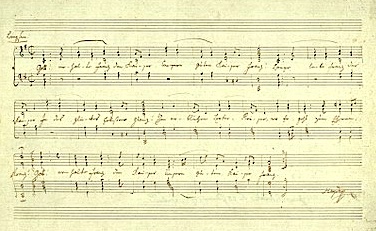

And some pages from Li Qing’s copy of the manual:

Pp.1b–2a. Third line from right: the Naihe qianchi lang couplet,

followed by 7-, 5-, and 4-word mantras.

Verso: the talisman for the Heavenly Official.

And we can compare these pages with Li Peisen’s copy above:

Recto: template for slip to Rescue from Suffering, “in red characters, with white envelope”.

Slips for Long Life.

The ritual as performed in 1991

We can soon discover that the version performed that day by Li Qing and his colleagues (and again, do watch my film, from 48.35) bears little relation to that given in the manual.

First, in the scripture hall, Li Qing copies the lengthy series of pardon slips with their talismans, and envelopes to put them in—a lengthy process, for which he consults Li Peisen’s manual.

Meanwhile, in light snow, the other Daoists construct an open-air altar in a large clearing in the middle of the village near the funerary site, using tables, benches, and planks. On this structure are placed in a row five “palaces”—cardboard images mounted on stalks of gaoliang inserted into large rectangular dou bowls filled with grain—for the Jade Emperor Yuhuang, the Three Officers (sanguan, for heaven, earth, and water), and the pole star Purple Tenuity (Ziwei, not mentioned in the manual).

Just below the central palace to the Jade Emperor is an altar table bearing the soul tablet, and below that, a long table around which the Daoists will stand to make offerings to the five palaces. Further behind, facing the palaces, a long high platform has been built on top of tables, from where the Daoists will later dispatch the writs of Pardon.

Around midday, after the morning visits to Deliver the Scriptures, the seven Daoists proceed from their scripture hall, playing percussion with occasional blasts on the conch. After paying a brief visit to the soul hall, they purify the arena by leading the kin on an elaborate winding procession around it. Virtually all the villagers have gathered round—by contrast with their apathy today, gorging instead on the pop music outside the gate.

The ritual is in two large sections: presenting the offerings from the altar table, and announcing the writs of pardon from the ritual platform before handing them down to the kin to be burned.

Acting as intermediary for the kin standing in a row behind him, the chief celebrant Li Qing, wielding his wooden “court placard” (chaoban) and sounding a hand-bell and a qing bowl on the table, now faces the altars and presents offerings to each of the five deities in turn on behalf of the kin. An offerings tray (of red lacquered wood, not like the metal one used now) is at first placed on the altar table before the god palaces.

While the Daoists play an instrumental piece (for this next sequence the two sheng accompany not the guanzi oboe but the dizi flute), Li Qing bids the oldest son to wash his face from water in a bowl and offer one preliminary stick of incense to the palace of the Jade Emperor. After he shakes the bell and strikes the qing bowl, the Daoists sing a sequence of a cappella choral hymns from the “words of blessing” (zhuyan 祝言) repertoire, accompanied only by the ritual percussion, beginning with Myriad Years to Elder Emperor (Huangdiye wansui). These hymns are punctuated by imposing patterns on nao and bo cymbals.

Li Qing recites a brief shuowen introit while the tray is handed to the oldest son of the deceased. Again accompanied by dizi, he takes the court placard, bows with it, and one by one places five cups of tea, with incense resting on them, on his court placard to transfer them onto a small raised table before the central palace to the Jade Emperor. The sticks of incense are then further placed before the god palaces, accompanied by dizi. After each offering they sing another a cappella hymn from the “words of blessing”.

Li Qing now clambers up onto the table, taking bell and placard with him. He leads the Daoists as they solemnly intone the two couplets “Thousand-foot waves at Bridge of No Return” (Naihe qianchi lang, from p.1b of the manual, also used at the end of the Invitation, my film from 1.03.25). Whereas the first sequence was punctuated by jaunty dizi, for this new sequence the hymns are to be accompanied by solemn shengguan wind ensemble, punctuated with interludes on large cymbals, while Li Qing kneels on the table, bows with the placard, and transfers the remaining offerings (incense, flowers, and so on) in turn before the god images, always placing them on the placard first. He recites another shuowen introit, shakes the bell, and the Daoists play another piece with dizi while Li Qing steps down from the table.

Then, taking all their ritual and musical instruments with them, the Daoists ascend the platform behind, standing in a long line behind a long row of tables to face the altars. As a majestic prelude they play the percussion piece Yellow Dragon Thrice Transforms Its Body.

Wang Chang recites a pardon writ from the ritual platform,

with Li Qing and Yuan Lishan further to our left;

to the right are Li Peisen’s grandson Li Yushan and a youthful Wu Mei.

Then the three leading officiants (Li Qing, Wang Chang, and Yuan Lishan) don five-buddhas hats, representing the Three Officers. The group plays The Five Offerings (Wu gongyang 五供養) on shengguan, and then the three officiants, in turn, solemnly read out the large and lengthy pardon slips. The first is read by Yuan Lishan. Li Qing calls out an instruction, folds the document up and places it in a large envelope, folds over the strip of paper to “seal” it, handing it down to the kin, again accompanied by the ensemble with dizi. The documents, envelopes, and seals are all of different colours, as specified in the manual.

Li Qing shakes the bell, recites a shuowen introit, and they sing the hymn Ten Repayments for Kindness (Shi bao’en 十報恩) with shengguan, another item common to several rituals. Li Qing recites a shuowen, and they play the cymbal interlude Sanqi song. Another shuowen leads into the second reading by Li Qing. Then a shuowen leads into a shengguan piece, which segues into a protracted “catching the tiger” clowning sequence.

Wang Chang, the main guanzi player, standing to the left of Li Qing, plays two guanzi alternately and then at once, blows the mahan small telescopic curved trumpet, dismantles his instruments while playing them, plays a hefty whistle in his mouth, pretends to pluck snot from Li Qing’s nose and smear it over the face of the sheng player on his left, replaces the latter’s cap with a cymbal, puts on false eyes, and makes ribald gestures with the curved trumpet. Li Qing and the others try to keep a straight face throughout, but Wang Chang is having fun, and the villagers are in stitches.

Li Qing now recites a shuowen, followed by a percussion interlude. Then he recites the final pardon document, folds it up, places it in its envelope, and hands it down, accompanied by Sizi zhenyan 四子真言 on dizi. Finally, the Daoists descend from the platform, playing shengguan, and lead the kin on a slow parade around the arena. Li Qing guides the kin in the burning of the memorials in a pile together, while the Daoists stand round playing shengguan. They then retire to their scripture hall to rest and prepare for the next ritual segment.

Manual and practice

In sum, although we didn’t quite film the Pardon complete, they evidently didn’t perform the manual complete either. Li Qing was quite familiar with the text—he had lovingly copied it out a few years earlier. We can only surmise how often the senior Daoists Li Qing, Wang Chang, Yuan Lishan, and Li Yuanmao had performed the ritual before the 1950s with Li Peisen and others from that generation, but whereas they had maintained the “inner five rituals”, by 1991 their recollection of the Pardon may have been hazy, and the younger Daoists were quite unfamiliar with it. So perhaps this explains why the ritual was so transformed. Alas, on my first visits I lacked the background to consult Li Qing about such matters.

It is likely that sections like the Yellow Dragon percussion item and the “catching the tiger” sequence, though not specified in the manual, were traditionally included. But instead of the long series of four-, five-, and seven-word mantras in the manual, they alternated a cappella “words of blessing” from the Diverse Rituals for Joyous Scriptures (Xijing zayi 喜經雜儀) compendium for “earth scriptures” with an instrumental refrain using dizi, and sang standard “floating” hymns with shengguan. I suspect this was actually a version of the Noon Thanksgiving for temple fairs and Thanking the Earth, though the texts they performed also differed from those in the Xiewu ke 謝午科 manual. Only their final recitations of the Pardon writs appear to have been performed more or less intact as in the Pardon manual.

Anyway, rather as the temple fair sequence since the late 1980s seems to be a revision, this was already an adapted version. The ritual is lengthy and imposing, and its purpose is communicated, but it tallies only occasionally with the manual. With the same diligence that he had preserved the original content of the manuals, Li Qing was now selectively adapting rituals according to changing conditions—as Daoists (and other ritual specialists) have done throughout history; but it marks a substantial break with tradition.

Of course, scholars of Daoism may be more interested in the manual, which undoubtedly preserves early features. But (like the 1940s’ temple fair sequence) we can’t now witness it being performed; there is no demand for it among patrons, and even if we requested it specially, the current Daoists would be hard-put to recreate even Li Qing’s 1991 version, let alone attempting to perform it as shown in the manual. Even the “words of blessing” and the dizi interludes (which themselves may have been a substitute) are no longer part of their repertoire. For continuing ritual change, see A flawed funeral.

The Pardon elsewhere

The Pardon is commonly performed by household Daoists in southeast China, the heartland of research on Daoist ritual. For Taiwan it has been described in detail by John Lagerwey (based on the practice of the great Chen Rongsheng) and Jiang Shoucheng; and Ken Dean has documented it for south Fujian. [1]

While the text of Chen Rongsheng’s version appears different, its themes are similar. Apart from the mystical core of the ritual, Lagerwey draws attention to its dramatic, jocular interlude. In Yanggao such elements are absent from the manual, but an interesting connection seems to be implied in the “catching the tiger” sequence.

Lagerwey cites the 13th-century Daoist priest Wang Qizhen:

This Pardon document does not belong to our method for doing the fast. It is the invention of later people. Given the fact, however, that it has been used far and wide for some time, it would not do to eliminate it.

And he too notes variation between the early manual and modern practice.

For north China I have only a few other instances so far. [2] In Julu, south Hebei, it was performed on the afternoon of the 3rd day of funerals, comprising the segments qingshen 清神, ji lengshui 祭冷水, qing Yuhuang 請玉皇, song wulao 送五老, qing jianzhai 請監齋, and zhuan dagong 轉大供.

And in the jiao Offering around Baiyunshan in Shaanbei, again on the afternoon of the 3rd day, the Pardon is a spectacular (if not highly liturgical) ritual, with large god puppets of the Eight Immortals and the Four Officers of Merit (Sizhi Gongcao 四值功曹) descending on a rope down from the hillside to the bank of the Yellow River—somewhat reminiscent of the guandeng Beholding the Lanterns nocturnal ritual around Beijing (see here, under “A Buddhist and Daoist funeral”), on a far grander scale.

Back in north Shanxi, in Tianzhen county just east of Yanggao, the Lü family of household Complete Perfection Daoists, whose tradition derives from the Nanmen si temple in Huai’an nearby, have a tradition of performing the Pardon, though it now seems to be defunct. Their lengthy manual, apparently copied in the Republican era, is entitled Taishang shuo Yuhuang shezui 太上玉皇說赦罪 or Yuhuang shezui tianzun shenjing 玉皇赦罪天尊神經. They also have a template for the writs of Pardon (“Pardon slips” shetiao 赦條):

Back in north Shanxi, in Tianzhen county just east of Yanggao, the Lü family of household Complete Perfection Daoists, whose tradition derives from the Nanmen si temple in Huai’an nearby, have a tradition of performing the Pardon, though it now seems to be defunct. Their lengthy manual, apparently copied in the Republican era, is entitled Taishang shuo Yuhuang shezui 太上玉皇說赦罪 or Yuhuang shezui tianzun shenjing 玉皇赦罪天尊神經. They also have a template for the writs of Pardon (“Pardon slips” shetiao 赦條):

Aided by Lagerwey’s discussion, scholars of early Daoism will wish to trace the ancestry of “pardon for sins” (shezui 赦罪) in the Daoist Canon, with many sources following the Yuhuang shezui cifu baochan 玉皇赦罪賜福寶懺. Meanwhile, ethnographers are left to observe modern changes in the ritual adaptations of Daoists and patrons.

[1] See Lagerwey, Taoist ritual in Chinese society and history (1987), pp.202–215, Jiang Shoucheng 姜守誠, “Nan Taiwan Lingbaopai fangshe keyi zhi yanjiu” 南台灣靈寶派放赦科儀之研究 (2010); Dean, “Funerals in Fujian” (1988), pp.45, 52–53. Cf. Pregadio, Encyclopedia of Taoism (2008), pp.403–404.

[2] Based on my In search of the folk Daoists of north China, pp.91 and 99–100. The Julu material is from Yuan Jingfang 袁靜芳, Hebei Julu daojiao fashi yinyue 河北鉅鹿道教法事音樂 (1997), pp.72–4; for Baiyunshan, see e.g. Yuan Jingfang et al., Shaanxi sheng Jiaxian Baiyunguan daojiao yinyue 陝西省佳縣白雲觀道教音樂 (1999), pp.112–13, and Zhang Zhentao 张振涛, Zhuye qiuyue lu 诸野求乐录 (2002), pp.149–50.

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

Lingbao kaifang shezhao yubao xianzhuan youlian poyu fangshe duqiao zhu baiyu rang huangwen [ke] 靈寶開放[方]攝召 預報獻饌遊蓮破獄放赦渡橋祝白雨禳蝗瘟[科]

Back in north Shanxi, in

Back in north Shanxi, in