In the 1990s, ritual activity in the southern rural areas of the municipality of Beijing was patchy. While we found few ritual associations in the counties of Gu’an, Fangshan, and Zhuozhou south of the city, the groups in the suburban counties of Daxing and Tongxian, southeast of Beijing, were still actively providing ritual services.

Like other associations on the Hebei plain, these groups have ongoing ritual traditions, and clear links to Daoist priests and Buddhist monks. But these groups are distinguished by their proximity to Beijing, and by the fact that many groups acquired their ritual only in the 1950s, as laicized clerics sought to transmit their knowledge to villagers. Thus although they are not “old associations”, lacking the early history of most village groups that we found just further south on the plain, they clearly reflect temple traditions of ritual, relating to Beijing and Tianjin as well as to local networks. [1] Again by contrast with most amateur village associations elsewhere on the Hebei plain, many of these groups don costumes for rituals, and accept fees.

This whole region was still largely rural when we made fieldwork trips there in the 1990s, but has since been absorbed into the ever-expanding urban sprawl of suburban Beijing—as indeed are villages further south on the plain, where we found many more ritual associations. In a physical and moral landscape that has changed constantly since the 1930s, restudies are always to be desired.

There are many such groups here, but here I’ll focus on two:

- The Lijiawu Daoist group, derived from the temple priests of Liangshanpo, and

- the Buddhist-transmitted group of North Xinzhuang nearby.

This article also complements my various posts on Beijing temples and the transmissions south to villages like Qujiaying.

The Liangshanpo Daoists

Several village ritual associations in this area learnt only in the early 1950s from the Complete Perfection Daoist priests (known as laodao 老道, a common colloquial term) of the Liangshanpo temple, properly called Pantaogong Liangshanpo 蟠桃宮良(梁)善坡, in Zhangziying district of Daxing county. [2]

Apart from Houshan further west, in the area south of Beijing this was the largest of the former Daoist temples that we found with a clerical staff who performed rituals among the folk. It was also known as Wangmu niangniang miao 王母娘娘廟; its main temple fair, the sanyuesan pantaohui 三月三蟠桃會, was for Wangmu’s birthday from 3rd moon 1st to 3rd; they also used to take a sedan (jia 駕) of the Niangnang deity on procession due south to Shanggezhuang for the 4th-moon temple fair there.

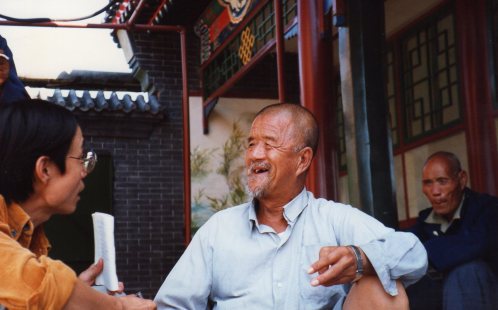

In 1993 we met two surviving former Daoists from the temple, Gao Liwang 高理旺 (b. c1923) and Zhang Liwang 張理旺 (known by his secular name of Zhang Fugui, b. c1928). The li component of their given names indicated the 22nd generation, as in the 100-character Longmen Complete Perfection poem (beginning da dao tong xuan jing 大道通玄靜) that Zhang recited for us. [3] We found Gao Liwang in the local old-people’s home (cf. the wonderful story here), which he had entered in 1987.

Gao Liwang chats with Xue Yibing, 1993.

The Liangshanpo temple belonged to the Qiuzu Longmen lineage of the Complete Perfection order; Zhang said it was a “subsidiary cloister” (fenyuan) of the White Cloud Temple in Beijing. Since Lingbao liturgy was subsumed under Complete Perfection practice, Gao claimed that they were “Lingbao Complete Perfection branch”, and Zhang Fugui also said they recited Lingbao jing 靈寶經 and Lingbao shishi yankou 靈寶施食焰口. It was quite a large and affluent temple, with three qing of land (liangtian 良田), whose grain they sold to pay for upkeep. They hung out their Ten Kings paintings when they went to perform funerals.

Gao Liwang, whose old home was in Zhangziying, became a Daoist priest at Liangshanpo in 1939, learning to play the sheng mouth-organ with Li Zhihui 李志慧 (then 52 sui). That very year the temple was partly burned down by the Japanese. Zhang Fugui, Gao’s former fellow-priest at Liangshanpo, entered the temple when 16 sui (c1943), also taking the Daoist name Liwang.

In that period, Gao recalled, there were seven priests in residence, who recited the scriptures and played shengguan for folk rituals: himself, his master Li Zhihui (then abbot [dangjiade 當家的, a very common term for boss of any ritual or indeed secular group], known as Third Ox, Sanniu), Ma Zhikang, Zhang Fugui, his master Kang Zhixi, Cheng Zhishan, and Liu Lixiu. Zhang Fugui recalled two more priests from the elder generation, Jia Zhiqing (Black Dog, Heigou), and Liu Zhijiang.

Just after Liberation, apart from Gao Liwang and Liu Lixiu, Lijiawu villagers recalled two further active temple Daoists: Xu Lixin and Zhang Licai. We met still others in the Upper Zhangziying association in 1995 (see below).

In 1943 Gao Liwang left to join the Communist Eighth Route Army against the Japanese, going on to fight the Nationalists in the civil war. After Liberation in 1949 he returned to the Liangshanpo temple “to till the fields”—though most of the temple land was confiscated for Lijiawu village—and to resume folk ritual. In 1950 he and fellow Daoist Liu Lixiu 劉理秀 (c1910–1980, mainly a guanzi player) taught vocal liturgy and shengguan music to Lijiawu villagers, going on to do funerals with the new association there. Meanwhile Zhang Fugui, unable to stay on in the temple, served at the Yuhuang miao temple in Tianjin city from 1949 to 1950 (he also recalled the Lüzu tang and Chenghuang miao there as having household Daoists). But when he wasn’t allowed to stay there either, he returned to his old home at East Beitaizhuang in Zhuzhuang district, becoming a peasant, folk vet, and book-keeper; by the 1990s he had opened a general store.

The way that Liangshanpo priests taught Lijiawu villagers its vocal liturgy and shengguan in 1950 may sound typical of temple–lay transmissions, but actually, until not long before then, they seem to have behaved more like an “orthodox” Complete Perfection priests, without any melodic instrumental music of their own. While the accounts of Gao and Zhang about how the temple first acquired shengguan defy my most diligent efforts at reconciliation, the following account at least shows that the temple had only added that component a generation or so earlier.

Zhang recalled that Liangshanpo was most closely linked to the Li’er si 李二寺 temple in Zhangjiawan district of nearby Tongzhou, [4] with whose priests they also used to make up a band together for folk ritual. The Li’er si was to the eight immortals. Unlike the priests of Liangshanpo, the priests there played shengguan. One day, the Liangshanpo priests of the generation senior to Zhang, no longer willing to remunerate the Li’er si Daoists so heavily, decided to learn the shengguan wind ensemble music themselves, inviting the locally celebrated Ma family from Southgate of Wuqing county-town. To pay for tuition they sold off 80 mu of land and some trees, and three Daoists started to learn: Li Zhihui, Jia Zhiqing, and Liu Zhijiang. Alas, we didn’t clarify whether the Ma family were household Daoists or a lay group, but it seems an amazing reversal of the commonly-heard story: usually it is villagers who decide to save money by themselves learning ritual and shengguan from priests, but here we find the Daoists learning shengguan from villagers! Zhang also mentioned that if the Liangshanpo Daoists needed to make up numbers, they could link up with the nearby Daoist bands in Aigezhuang or North Jianta—or even, if patrons were more choosey or affluent, with the Yuhuang miao temple in Tianjin.

The Liangshanpo temple was further damaged in 1954 when the county authorities needed wood to make the new county hall; in 1958 the temple was destroyed, and Gao Liwang again returned to lay life in Zhangziying, still performing folk ritual for some years.

Jinran shendeng hymn from Guandeng gongde jingshu (left), and opening of shishi manual.

Zhang Fugui showed us the copy of a yankou manual (titled Quanzhen qingjing shishi ke 全真清靜施食科) [5] that he had brought back from his sojourn at the Yuhuang miao temple in Tianjin in 1950; he also had a manual called Guandeng gongde jingshu 關燈功德經書 (a rare siting in north China of the term gongde). In 1979 he had copied the main features of his ritual practice into a small exercise book, including gongche scores of the shengguan music, mnemonics for the ritual percussion (several for specific rituals like Chasing Round the Five Quarters and Crossing the Bridges), and a section with ritual texts (zanian bu 雜念部, Lingbao ke 靈寶科). Zhang Fugui still liked to read the scriptures on his own at home, and memorized them as he rode along on his bicycle; he also played his guanzi (an exquisite old instrument) on his own at home for fun. He took part in the ritual association of his home village of East Beitaizhuang, which had fourteen members able to “take out the scriptures” (common term for performing rituals); the Lijiawu association sometimes invited some of them to help make up numbers.

Village transmissions

In 1993 visits to Lijiawu village, known as Lifu, we talked with the association leaders, notably Zhang Fengxiang (b. c1929), who was not only chief liturgist, and a sheng player, but was also village chief (a common pattern in the Hebei associations). The association then had seventeen members, including twelve instrumentalists.

As we saw above, the Lijiawu villagers had learnt in 1950 from the Liangshanpo Daoist priests Liu Lixiu and Gao Liwang, with whom they continued to do funerals for some years. They inherited the temple’s ritual manuals, costumes, instruments, and shengguan score, but most were confiscated before the Cultural Revolution; two sets of ritual manuals were burned during the Cultural Revolution. By 1993 they had both new Daoist robes and some surviving old ones. The latter (some said they came from the Liangshanpo Daoists, but Zhang Fugui said they were bought from Tianjin soon after Liberation) were still more ornate, embroidered with the Eight Immortals; they had water sleeves (shuixiu), like female opera costumes.

For the funerary Visiting the Soul (jianling 薦靈) ritual the Lijiawu Daoists dress up and perform the Songjing gongde 誦經功德 hymn; the ritual leader (zhengnian 正念) clasps two tieyiban 貼義板 placards, one inscribed Penglai xianjing 蓬萊仙境, the other Liangyuan guizhen 良苑歸貞. For the Communicating the Lanterns (guandeng) ritual, they sing the Jinran shendeng 謹燃神燈 hymn, with shengguan accompaniment (duikou 對口). Their Visiting the Soul, Chasing Round the Quarters, Beholding the Lanterns, Crossing the Bridges, and yankou rituals all include duikou pieces.

In Upper Zhangziying village, Gao Rongshui (b. c1940) told us that the association there had been founded in his grandfather’s time, by learning with the Liangshanpo Daoists. He himself had learnt the ritual since the age of 17 sui with Gao Ruixiang; they had been quite busy performing until the Cultural Revolution. Gao Rongshui had been association head (here called liaoshi 了事) [6] since 1988. Two months before we met them in 1995 they had begun training a new group (yipeng 一棚) of young men to learn both vocal liturgy and shengguan. Though they, like the other groups in this area, are handsomely paid for performing rituals, their training reflected old moral values: they were taught not to engage in gambling or whoring.

The ritual elders in the group were former Liangshanpo Daoists. Zheng Wencai (b. c1916, Daoist name Lijing) studied shengguan in the temple with Li Zhihui, scriptures (jing) from Zhao Mingzhi, and vocal liturgy (yun) from Xu Yuanbin; his master (shiye) was Feng Mingshan (in the generational poem, the 19th–21st characters are yuan–ming–zhi). His younger brother Zheng Wenxue (b. c1919) began performing Daoist ritual aged 11 sui, learning with his father Zheng Jinbang; from their names, it is not apparent if Wenxue and his father were temple Daoists, and I’m afraid we didn’t clarify this, but the tradition is evidently the same. The father and two sons were considered great liturgists.

Guxian village in Langfang also claims transmission from the Liangshanpo temple. We didn’t manage to visit another recommended ritual association with “Daoist scriptures” (laodaojing) at Longmenzhuang in Fengheying district.

Buddhist-transmitted groups

In this region there were just as many Buddhist-transmitted lay groups. Still in Zhangziying district, the North Xinzhuang village ritual association (again called yinyuehui) is rather exceptional, in that they are occupational. They learnt only from 1951; as we saw, folk ritual here before Liberation seems to have been mainly performed by clerics in the local temples. [7]

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

On the eve of Liberation, the village Guandi miao temple had five Buddhist monks: Daguang, his master, and three of Daguang’s disciples, who performed folk ritual, including shengguan music. The temple images were destroyed in 1950, and the priests had to leave the temple; most returned to their old families, but Daguang (c1887–1966), had no family to go to, so he remained in the temple. It was he who was to teach the villagers, and he was revered by all who knew him. As he told his disciples, his surname was Cui 崔; he came from a village in Gu’an county, becoming a priest when 12 sui at the Zaolin si temple, perhaps in suburban Beijing. He had learnt ritual percussion at a temple in Huangxindian, and shengguan at a temple in Aoxiaoying, and also spent time in a temple in Xianghe county before settling in the Guandi miao in North Xinzhuang.

Like many monks, Daguang used to smoke opium; it was often part of their reward for performing funerals. After 1949 he had to kick the habit. During land reform, he was allotted land, but he couldn’t cultivate it, and since several youngsters in the village liked the shengguan ritual wind ensemble, he agreed to let them cultivate his land in exchange for teaching them. He took three sets of disciples, in 1951, 1954, and 1956, who still formed the core of the association by the 1990s.

Under the commune system, unable to gain work-points while out doing folk funerals and thus absent from production, the new ritual specialists were awarded a full day’s work-points in exchange for 1 yuan each (a common arrangement, noted in my two books Ritual and music of north China).

They still treasure a rare and astounding photograph of the pupils with Daguang, all in fine Buddhist robes and with instruments, taken on the eighth anniversary of the association—at the extraordinary time of 1959, with famine escalating after the frantic mobilizations of the Great Leap Forward.

Daguang (centre) with his disciples, North Xinzhuang 1959.

But in 1963 their instruments, costumes, and paintings (all from the temple) were confiscated by the Four Cleanups work-team to form part of an exhibition to show the evils of superstition, and they had to stop activity. Daguang, criticized and then neglected, died in August 1966, soon after the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. After the association restored in 1978, one of their first acts was to claim back their artefacts from the Daxing Hall of Culture, but since four costumes and some other effects had been handed over to higher authorities, the Daxing county government eventually gave them 1,000 yuan in compensation.

Note “Guandi miao” on right.

Like the Daoist ritual associations in Daxing, the fact that they learned only in the 1950s from a cleric explains how it was that they now took money for funerals, unlike the amateur tradition of most old village ritual associations just south. On our visits the association had some fine musicians, and they were very keen; the huitou leader (a post here again called liaoshi, as in Zhangziying) was Shi Huaishen (b. c1926), a respected ritual specialist. They were still playing instruments inherited from Daguang, such as the guanzi oboe that Lian Kui (b. c1933) was playing, and a superb yunluo frame of pitched gongs. They also still had a set of paintings called “the Seventy-two Courts” (qishier si 七十二司), resembling the more common Ten Kings. [8] Though they still performed some vocal liturgy for funerals, they regretted having forgotten some of the ritual pieces that Daguang taught them, like those for Raising the Coffin qiguan 起棺 and jieshi 借時 (?).

In Upper Zhangziying district, Baimiao village also used to have a Buddhist-transmitted association. We spent some time in 1993 with two further Buddhist-transmitted associations in the area, those of Lesser Heifa and Shicun villages; I will introduce the latter here.

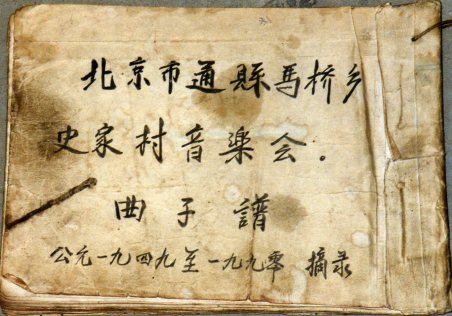

In Majuqiao district of Tongxian county (as it was then), the ritual association of Shicun (Shijiacun) also had a modern Buddhist transmission (sengmen 僧門). I met them at a secular performance in Beijing in 1993, and we visited them at home later. Their huitou leader was the fine guanzi player Li Lianrong (b. c1929).

Shicun ritual association performing in Beijing, 1993.

They learnt in 1949 from the village Guanyin si temple, founded in the Ming dynasty. A subsidiary temple of the Guangji si in the Xisi quarter of Beijing (another “orthodox” temple without shengguan wind ensemble), it was thought to have acquired shengguan music in the Qing dynasty. Its abbot (fangzhang) Wuran 悟然 went to the Guangji si in 1917 to be abbot there; his master there was Benyong 本勇. The village temple was destroyed and the monks driven away soon after Liberation, but in 1949 Wuran’s disciple Changji 昌繼, the only priest then remaining in the temple, taught shengguan to fifteen or sixteen of the Shicun villagers. He played sheng; they learned guanzi from the monk Shenglin from Aoxiaoying village nearby. Their gongche melodic score was copied from that of the Guanyin si temple. Again, the Shicun villagers learnt the shengguan more than the vocal liturgy. They held a further recruitment in 1962; having stopped around 1964 with the Four Cleanups campaign, they recruited again only in 1990.

Title page of gongche score, Shicun.

Apart from funerals, and the New Year’s rituals around 1st moon 15th (here called Spreading Lantern Flowers, sa denghua 撒燈花), they also observed 2nd moon 19th, 4th moon 8th, and the Medicine King (Yaowang) festival on 4th moon 28th.

Though I often try to expurgate too much detail on the shengguan wind music, this may be a suitable place to remind the reader that not only is it a ritual tradition derived from, and distinctive to, Buddhist and Daoist temples, with complex prescribed sequences of ancient melodies and scales, but that it is a most exquisite solemn aspect of northern ritual performance.

A Buddhist and Daoist funeral

A funeral like that I attended at Upper Zhangziying village on 13th March 1995 brought all the old Daoists from Liangshanpo out of the woodwork. It was a lavish funeral for a 70-sui old man who had died on the 11th, with three ritual associations taking part: the Buddhist North Xinzhuang band, and the Daoist Lijiawu and Upper Zhangziying groups. However, the main rituals took place only on the one day before the burial next morning. Unlike the earth burial that remains universal for rural funerals, in this Beijing suburb cremation is enforced, but the traditional rituals are still observed before the coffin is taken off to the crematorium.

The vocabulary here evokes that of the brilliant works of Chang Renchun for the ritual life of old Beijing.

The three groups were each given their own house to prepare, change costumes, be fed, and rest between visits to the soul hall. [9] On the long procession in both directions between this base and the soul hall, they played magnificent shengguan in prescribed sequences with percussion interludes, led by a grandson carrying the soul tablet (lingpai) (and on later visits a god tablet paiwei) on a tray. The processions of the three groups to the soul hall (lingtang) were usually separate, the North Xinzhuang Buddhists always beginning the sequence, reflecting the traditionally greater prestige (though not actual popularity) of Buddhist monks (as in the expression “first Buddhist monks, then Daoist priests” xianseng houdao).

- 11.20am–12pm: Settling the Stove (anjian 安尖, anzao 安灶) and first Visiting the Soul (jianling 薦靈). On arrival from their procession, each of the three groups first visits the kitchen to pay homage to the kitchen god, playing shengguan and a hymn with shengguan accompaniment, while a grandson stands before the kitchen with a soul tablet. Then for their first Visiting the Soul ritual, they play a short percussion interlude as they move over to stand before the soul hall and its altar table, the chief celebrant (wielding a hand-bell or a placard) facing the coffin, as they sing a solemn hymn to accompaniment of ritual percussion, followed by another hymn with shengguan. Meanwhile the grandson continues kneeling as the soul tablet is placed on the altar table. As they leave, the female kin (who have been kneeling to the side of the coffin throughout, burning spirit money) begin to wail. In quick succession, as each association begins the long parade back to its base, still playing shengguan, the next one arrives. After lunch,

- 1.30–2.45pm: the second Visiting the Soul, with the three bands in succession again. The leader of the Zhangziying Daoists sings the Song of the Skeleton (Kulou ge or Tan kulou)—an important ritual song in imperial Beijing, still sung by many ritual associations on the Hebei plain (In search of the folk Daoists, Appendix 2; cf. Yanggao).

- 3.30–4.15pm: the third Visiting the Soul. (The number of visits is not fixed, depending on the requirements of the funeral family and the whole atmosphere, how many people have come, and so on.)

Recently-copied texts for Chasing Round the Quarters, Lijiawu 1993.

Between the various jianling Visiting the soul rituals they might also insert Crossing the Bridges, and then either Chasing Round the Quarters (paofang) or Smashing the Hells (poyu). This was the only place where we heard “paofang bu poyu, poyu bu paofang” 跑方不破獄, 破獄不跑方, indicating that Chasing Round the Quarters is performed for the funeral of a male, Smashing the Hells for that of a female. [10] Was this unique to this small area, or was it a general rule that all our interviews elsewhere somehow failed to elicit? I have rather few instances of alternative rituals for male or female deaths in north China. [11]

- After the last visit to the soul is a brief tan wangling 嘆亡靈 (jingzhai 淨宅) ritual, the North Xinzhuang group (led as ever by a grandson of the deceased) entering the house where the deceased breathed their last, to play a brief shengguan piece by way of exorcism.

- 4.30–6pm songsan 送三, a public procession through the village. The kin assemble, and all three ritual groups. Leading the procession are helpers carrying the three items to be escorted away: the soul tablet (representing the deceased), the paper horse and cart (the deceased’s transport to heaven), and paper lanterns (to illuminate the way for the deceased). A paper streamer brought from the soul hall is first animated by a group of women (perhaps mediums) with water, a comb, and a mirror. Next come the three ritual groups, led by a grandson bearing a soul tablet. More kin and villagers bring up the rear. The three ritual groups follow the paper artefacts, playing upbeat shengguan all the way, stopping sometimes to perform extrovert clowning and tricks with the instruments (the Daoists now stealing the show). At the edge of the village they stop, still playing shengguan, while the kin continue just outside the village to burn the paper artefacts. At a funeral nearby a few days earlier, they also burnt the funerary sticks, decorated at their base with white paper, with which the kin symbolically swept the route; they wailed as they kneeled.

- 6.20-6.40pm: Sealing the Soul (fengling 封靈). As the kin kneel on either side of the coffin, at the bidding of the master of ceremonies, they go in same-sex pairs to kneel before the coffin, kowtow, and use chopsticks to place morsels of food from the altar table into a jar (the ritual is thus also known as jianguan 搛罐); this jar is to be buried with the coffin. The master of ceremonies meanwhile pours some tea before the altar (hence the alternative title diancha Libations of Tea for this ritual, though with no liturgical/ritual content). This ritual is accompanied not by the ritual specialists but by a shawm band (chuigushou) playing short popular pieces, seated before the coffin—surely a relaxation of the traditional rule whereby only the ritual specialists can take their place directly before the coffin/altar, whereas the shawm band always stand to one side. The shawm band did not take part in the previous songsan procession.

At the funeral a few days earlier, after a brief Thanking the Stove [god] (liaozao 了灶or xiezao 謝灶) procession, the Buddhist association accompanied the kin to the crossroads just outside the other end of the village to burn the paper baofu envelopes stuffed with ritual money, the association again stopping at the edge of the village to play shengguan.

In the evening, two popular video films are shown on a projector in the street. After supper (the associations eating after the guests),

- 10pm–1am: Beholding the Lanterns (guandeng). This ritual is a rather rare survival from that of old Beijing. It is held in the large tent where the guests had eaten, in the courtyard near the soul hall. First three Buddhist liturgists (now in their black robes) sing vocal liturgy before the coffin. The rest of the group then plays percussion as they proceed over to the tent, where the three liturgists make offerings and sing a solemn hymn at an altar they have set up there, the chief celebrant wielding both hand-bell and dragon-headed incense holder. Meanwhile the other ritual groups have taken seats on either side of a long line of tables; the Daoists are now in plain clothes.

Over the table a rope pulley stretches, in two parallel lines, from which are suspended two cloth puppets (dengrenr 燈人儿), about 1.5 feet tall, one male and one female, perching on lotus flowers, each holding a little tray. First the three Buddhists face the tables to sing more vocal liturgy, interspersed with more ritual percussion, and the puppets begin to make their sedate journey along the rope, accompanied by all three groups. As a helper gently manipulates the pulley, at either end of the table a grandson of the deceased awaits; while one lights a ball of cotton wool, soaked in oil, from a candle and places it carefully on the little tray held by one puppet, the other grandson removes the ball from the other puppet as it reaches the other end. The puppets twirl round and begin their magical journey back along the rope, passing each other in different directions, swaying daintily back and forth as they deliver the lanterns to the deceased.

The three ritual groups take turns to play shengguan, with percussion interludes, in long accelerating sequences from solemn to extrovert. The Lijiawu group launches into more clowning, a young Daoist playing guanzi oboe with cigarettes in his nostrils, ears, and corners of his mouth (a staple of more secular wind bands in Hebei and elsewhere in north China), to cheers from the spectators. But the puppets’ journey is ever stately. Later, the Buddhists accompany the puppets with more vocal liturgy, now seated at the table.

It was only later that I read Chang Renchun’s typically detailed account of Beholding the Lanterns in old Beijing. Though this village ritual is nocturnal, a lot simpler, and a lot less liturgical, I suppose it might also remind us somewhat of the fangshe puppets of the Baiyunshan Daoists in Shaanbei (Ritual and music of north China, vol.2: Shaanbei, pp.99–100).

- We couldn’t attend the chubin 出殡 “burial” procession next day, but I had attended one a few days earlier at another funeral nearby with the North Xinzhuang association. Villagers came out to watch, with kin leading the way, the grandson leading the association behind, the coffin in a truck (not getting great fuel economy) bringing up the rear. Villagers could now “impede the association” (lanhui 攬會, cf. the Invitation in Yanggao), demanding popular pieces (folk-song, pop music)—this and the songsan procession are the only times they can depart from the solemn ritual style. The coffin was then taken off to the crematorium, the kin following in trucks, while the association returned to their home village.

Despite the spectacular participation of three ritual groups, this was a somewhat ritual-lite funeral, quite typical of funerals on the plain south of Beijing. Although I would argue against discounting the wealth of paraliturgical shengguan music, most of their more elaborate rituals (such as Chasing Round the Quarters, Crossing the Bridges, and yankou) were absent, and even the Beholding the Lanterns was notable more for the magic of the puppets than for its liturgy. As in north Shanxi, the main events were the repeated Visits to the Soul, in which vocal liturgy was mostly represented by single, albeit lengthy, hymns at each visit. This may be an impoverished scene, but to witness such rituals in performance, even today, must be a major part of our understanding of the ritual heritage from the Daoist priests and Buddhist monks of imperial times.

Conclusion

In sum, until the 1950s, even if the former Liangshanpo Daoists were temple-dwelling Complete Perfection priests, they and their heirs were busy doing folk ritual. Unlike most counties on the plain just south, this area didn’t have many lay ritual associations before 1949, and most of those that we found in the 1990s had learnt from monks or priests since 1949. So this also suggests in a bit more detail the kind of paths that might have led to the rituals of former Complete Perfection temple Daoists being spread among lay ritual specialists, as we found in other articles in this series.

Again, in this small area we’ve unearthed a considerable network of ritual and former temple groups, in a rather distinct style from those I’ve introduced further west around Laishui and Yixian.

For recent developments and the vast new Daxing airport, see here; cf. the impact of the Xiong’an megapolis on ritual traditions in Xiongxian and around the Baiyangdian lake.

[1] This article is based on my book In search of the folk Daoists of north China, ch.7, where you can find further refs.

[2] Zhangziying had indeed been colonized from Zhangzi in southeast Shanxi. Incidentally, in August 1967 Daxing was the site of one of the most notorious massacres of the Cultural Revolution, with 325 people killed (see Ian Johnson’s book Sparks, pp.185–7).

[3] The locus classicus today for all such lineage poems is Koyanagi’s list from 1934 (no.9). Versions transcribed from local Daoists over China have many variants—I’ve stuck with our 志, but changed our careless 李 to 理. Zhang’s version seems to get off to a shaky start, the more common version beginning dao de tong xuan jing 道德通玄靜; but I suppose only a few of these characters were ever used in practice in a group of local Daoists. To thicken the plot, Gao said he belonged to the 13th generation of “Lingbao Complete Perfection” Daoists.

[4] Mentioned in Li Wei-tsu, “On the cult of the four sacred animals in the neighbourhood of Peking”, Folklore studies 7 (1948), p.52, and also recalled by villagers in nearby Shicun.

[5] Unlikely to be linked to the Qingjing lineage of Complete Perfection, for which see the Encyclopedia of Taoism, pp.799–800, and under Koyanagi’s list, no.15.

[6] Cf. old Beijing: Chang Renchun, Hongbai xishi, p.292.

[7] Du Yaxiong, a most stimulating companion, introduced me to the village—even if his book gives a very different perspective from that of our team, rather following the old trend in Chinese musicology to seek “living fossils”. His version of their funeral sequence (pp.119–33) needs careful handling.

[8] Best known in the Dongyue miao in Beijing (where there are 76), Chen Bali, Beijing Dongyue miao (2002), pp.85–139. Cf. Ritual artisans in 1950s’ Beijing.

[9] Du Yaxiong (2004: 119) calls this danfang 單房; I didn’t hear the term used, but if they did use it, then perhaps it should be 丹房, as in Julu, south Hebei, where Yuan Jingfang (Julu daojiao yinyue, p.84) describes it as the site where the Daoists perform the scriptures; cf. the jingtang scripture hall in north Shanxi (my Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.27–8).

[10] Cf. Du Yaxiong 2004: 123–4.

[11] See my Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.32–3. There are textual (and sometimes ritual) alternatives for funerals in some other Hebei villages, including Gaoluo: see In search of the folk Daoists, pp.191–3. In Shuozhou, Shanxi, they perform Surrounding the Lotuses for female deaths. In Panjin, Liaoning (Li Runzhong 1986, vol.1: 52, 66), the male–female alternatives were paofang or duqiao! In southeast China, poyu, like the xuehu Blood Lake ritual, is prescribed for female deaths; e.g. Hakka ritual, po Fengdu or po diyu (Lagerwey, “Popular ritual specialists in west central Fujian”, p.456); in another county, po diyu was used for women who died in childbirth (ibid., p.484).