Li Manshan (2nd right) chatting with fellow villagers in Upper Liangyuan, March 2018.

I’ve just had an amazing time in China, both in the countryside and in Beijing (more anon). Still, it’s good to get back home—a feeling I described in my book (p.357):

Return of the Prophet (Not)

Back in this mild grey country, I begin writing up my notes over a stiff gin-and-tonic (à l’espagnol, easy on the tonic) as I listen to Bridget Christie [1] on BBC Radio 4, relishing cultural diversity again. My life has become schizophrenic; in London I meet up with a couple of friends maybe a dozen times a year, whereas in Yanggao, in the daily company of eight or more people morning to night, I am wrenched into constant socialising. This brings me alive and animates my reclusive life back home. Nigel Barley expresses the confusion of the homecoming fieldworker. [2] Returning from Cameroon, on an ill-fated stopover in Rome,

Café menus offered so many possibilities that I felt unable to cope: the absence of choice in Dowayoland had led to a total inability to make decisions. In the field, I had dreamed endlessly of orgiastic eating; now I lived on ham sandwiches.

And when he finally manages to get back to Blighty,

It is positively insulting how well the world functions without one. While the traveller has been away questioning his most basic assumptions, life has continued sweetly unruffled. Friends continue to collect matching French saucepans. The acacia at the foot of the lawn continues to come along nicely.

The returning anthropologist does not expect a hero’s welcome, but the casualness of some friends seems excessive. An hour after my arrival, I was phoned by one friend who merely remarked tersely, “Look, I don’t know where you’ve been but you left a pullover at my place nearly two years ago. When are you coming to collect it?”

Having immersed myself totally in Chinese cultures these last few weeks, with only occasional recourse to the Guardian just to remind myself there’s a world out there, this morning on Radio 3 I bask in Germaine Tailleferre, Astor Piazzolla, and Biber…

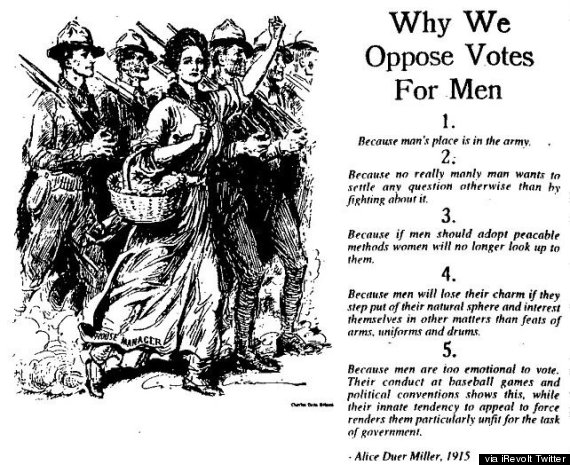

[1] Whose use of the classic London underground warning, I gladly concede, may well be more effective in feminist comedy than mine in Daoist ritual studies.

[2] Barley, The innocent anthropologist, pp. 184, 187.