In between the second and third waves of feminism came a remarkable book:

Regrettably, it’s out of print, but you can—and must—read it here. I first read the book soon after it was first published, and it remains an inspiring analysis, addressing the topic with dispassionate philosophical clarity.

In the Introduction she explains:

This book is a battle on two fronts. On the one hand, it takes issue with the many people who think that there is no justification for the existence of the feminist movement: the ones who think that women’s demand for equality with men was misguided in the first place, or that they have now got it, or that women are better off than men. On the other hand, it is equally against a good deal of feminist dogma and practice. For all the strength of the fundamental feminist case, feminists often weaken it by missing the strongest arguments in its support, or allowing themselves to get entangled in non-essential issues, or insisting on making integral to the feminist cause ideas which are either irrelevant, probably false, or actually against the interests of feminists and often everybody else as well. If the arguments which are to be presented here succeed in their intention, feminism will emerge from the enquiry as necessarily radical, but with firmer foundations, less vulnerability to attack, and at the same time more general acceptability than it has at present.

Her basic definition of the issue is broad:

Women suffer from systematic social injustice because of their sex.

Although people do usually think of feminists as being committed to particular ideologies and activities, rather than a very general belief that society is unjust to women, what is also undoubtedly true is that feminism is regarded by nearly everyone as the movement which represents the interests of women.

She notes the “apparently ineradicable human tendency to take sides”:

While it would be ideal if everyone could just assess each controversial problem on its own merits as it arose, what actually happens is that people usually start by deciding whose side they are on, and from then onwards tend to see everything that is said or done in the light of that alliance. The effects of this on the struggle for sexual justice have been very serious. The conflation of the idea of feminism as a particular ideology with that of feminism as a concern with women’s problems means that people who do not like what they see of the ideology (perhaps because they are keen on family life, or can’t imagine a world without hierarchies, or just don’t like unfeminine women) may also tend to brush aside, explain away, sneer at, or simply ignore all suggestions that women are seriously badly treated. Resistance to the feminist movement easily turns into a resistance to seeing that women have any problems at all.

Since there is no doubt that feminism is commonly thought of as having a monopoly on the representation of women’s interests, therefore, and since all feminists, however firm their ideological commitments, must want as many people as possible to be willing to listen to their arguments about the position of women rather than reacting with hostility whenever the subject of feminism comes up, it is in the interests of everyone who cares about justice to have as many people as possible thinking of themselves as feminists. That is the main reason why the wider definition is needed.

There is also another reason. If feminists themselves think of feminism as the movement which defends women’s interests and also as being ideologically committed in a particular direction, the effect will be to fossilise current feminist views. Any feminist who has the idea that giving up her current views is equivalent to giving up feminism may be very unwilling to look at her views critically and abandon them if they are implausible. But however committed any feminist may be to her ideology, she must allow that there is a difference between maintaining the ideology and accepting more generally that women are unjustly treated, and since human fallibility means that she may turn out to be wrong about the first, it seems better that feminism should be thought of as the wider of the two.

Thus she defines feminism as a movement for the elimination of sex-based injustice—which also allows men to count as feminists.

Admittedly, men claiming to be feminists have to be viewed with a certain amount of caution, since many have already discovered (sometimes without realising it) that pretensions to feminism are new and valuable weapons in the cause of male supremacy. […]

Some men are quite as capable of useful logical thinking and scientific investigation as women.

So it’s neither a movement of women nor a movement for women.

It obviously cannot be one which supports the interests of women under all circumstances, because there must be many situations where, even now, women treat men unjustly, and a movement concerned with justice cannot automatically take the side of any woman against any man. However, more subtly, feminism should not even regard itself as a movement to support women who suffer from injustice. This is because many injustices suffered by individual women have nothing to do with their sex, and could equally well be suffered by men. If, for instance, there are men and women in slavery, it is not the business of feminists to start freeing the women. Feminism is not concerned with a group of people it wants to benefit, but with a type of injustice it wants to eliminate. The distinction is important, even though on the whole the elimination of that injustice will benefit more women than men. Once again, this consequence of the new definition does no harm: on the contrary, it is far more reasonable to ask people to support a movement against injustice than a movement for women.

She makes a case for the philosophical approach, beyond debates about practical matters:

Feminism often suffers from staying too close to women, and not looking enough at the general principles which have to be worked out and then applied to women’s problems.

So the broader topics of the early chapters (“The fruits of unreason”, “The proper place of nature”, “Enquiries for liberators”, “Sexual justice”, all cogently argued) set the scene for her discussion of practical issues of specific concern in society. Here I’ll give a few instances of the latter.

Progress has since been made in some circles on some of the issues discussed in Chapter 5, “The feminist and the feminine”.

The fear that an emancipated woman must necessarily be an unfeminine one has always been the basis of one of the opposition’s main objections to feminism.

Femininity and masculinity are obviously not the same as maleness and femaleness. […] We must therefore be concerned with attributes which are in some way supposed to accompany these fundamentally sexual ones, and the question is of what kind of accompaniment is at issue.

As she notes, these attributes are the subject of much anxiety. The “desirable” quality of “femininity” “is obviously thought a very fragile thing, since so much trouble is gone to on its behalf”. Feminists are not concerned about any inherent characteristics differentiating the sexes; rather, they ponder the fact that

men and women are under different social pressures, encouraged to do different kinds of work, behave differently, and develop different characteristics.

She ably refutes Ruskin’s “sugary gloss of ‘equal but different’ “, and analyses direct and indirect social pressures. But the problem of eradicating the evils of culturally imposed femininity needs to be approached with some circumspection; she is wary of direct attacks on all forms of “femininity”. Among her arguments is people’s general appreciation of cultural differences;

While feminists must be committed to attacking all cultural distinctions which actually degrade women, the indiscriminate pursuit of an androgynous culture must involve the elimination of innocuous cultural differences as well, and with them the sources of a great deal of pleasure to many people.

In Chapter 6, “Woman’s work”, she first addresses the issue of “whether the work is of a kind which ought to be highly valued, or whether it is possible for it to be highly valued”. Then she considers the age-old dichotomy of public (male) and private (female) activity, and their different statuses:

If women’s work is private it is necessarily without status, and any promise to give it higher status must be vacuous.

She cites Betty Friedan’s story of a successful female journalist interviewing a housewife in 1949, who “has done nothing of what she planned to do in her youth, she has wasted her education, and she feels a general failure”.

“Then the author of the paean, who somehow never is a housewife, … roars with laughter. The trouble with you, she scolds, is you don’t realise you are expert in a dozen careers, simultaneously. ‘You might write: Business manager, cook, nurse, chauffeur, dressmaker, interior decorator, accountant, caterer, teacher, private secretary… you are one of the most successful women I know.’ “

As Betty Friedan rightly implies, this sort of thing is the purest rubbish, so entirely beside the point that it is hard to know where to begin criticising it. Its technique consists in totally ignoring the real complaint, pretending it is something else, and arguing that that something else is quite unjustified.

JRR does indeed go on to criticise the “patronising rubbish” of the “paean” with both care and passion. Yet such flapdoodle still went on when The sceptical feminist was written; and while progress has been made, it can still be heard today.

It is no part of feminism to insist that a woman should work at other things even though her children suffer as a consequence, but it is part of feminism to insist that there is something radically wrong with a system which forces so many women to choose between caring properly for their children and using their abilities fully. […]

It is not in the least obvious how this is to be done, but that is a reason for devoting the full energy and imagination of everyone who has any of either to trying to find a way. […]

To hold up home and family as the highest vocation of all is to try to cheat women into doing less than they might, and wasting their abilities.

She always puts the counter-argument—and then refutes it. She continues by considering goodness and altruism;

Women above all people are the ones who must resist the idea that the greatest good a woman can do is get on quietly with her limited work, because it is so transparently the result of men’s subjugation of women. […]

As long as the people who excel in the most important work are without status, it means that society undervalues their work, and as long as that happens society has the wrong values. […]

… What this suggests is that when women are indeed allowed to excel, even if they do it in slightly different areas from men’s, there is at least the possibility that things which are associated with women may become as highly regarded as the ones associated with men.

Since it may well be true that women will tend of their own volition to do different things (though of course we do not yet know), it is essential that we should try to make that equal respect come about.

Parts of Chapter 7, “The unadorned feminist”, may again appear somewhat dated, but while courting controversy she makes some most stimulating points.

There is no doubt at all that many feminists regard the rejection of “woman garbage” as a substantial issue, a thing which feminism ought to be committed to, rather than just a gesture. […]

Many feminists regard women who persist in clinging to their traditional trappings as traitors to the cause, while on the other hand to many non-feminists this austerity in the movement is one of its most unattractive aspects.

She explores the issues, starting with the obvious causes for feminist concern. First,

the amount of time, effort, and money which women are by convention expected to devote to their appearance, when no comparable demands are made of men. […]

If women are to succeed in the important things of life, it must be possible for them to be more negligent about dress, if they want to, without sacrificing social presentability in the process.

Further, the standards to be reached are impossibly high; mass culture allows for insufficient room for diversity; and the demands of the fashion industry are constricting. Of course, progress in such issues has been ongoing, and new generations of feminists have continued to probe them.

People have, after all, to choose their clothes whatever they are, and a feminist whose main motivation was to put as little time and money into them as possible should presumably go around in the first and cheapest thing she could find in a jumble sale, even if it happened to be a shapeless turquoise Crimplene dress with a pink cardigan. No feminist would be seen dead in any such thing. […] Style is important.

(Now I’m no fashion guru, but I rather think the outfit she parodies there would today be considered rather chic; still, it’s a good point.)

This is even clearer in the case of the great majority of feminists who do go to some little trouble to be clean and neat and pleasant. They too tend to go for the unfeminine feminist uniform, but this has obviously nothing to do with effort. With just as little effort, if they wanted to, they could wear all the time a single comfortable, pretty, simple, easily-washed, drip-dry dress, so avoiding all the problems of fashion, variety, time, money, and effort without giving up being pretty and feminine at the same time. […]

She ponders the issue further:

It is supposed to be bad to want people as objects of pleasure, but it cannot possibly be bad to want them because they give pleasure; there is no other possible basis for love than what is in some way pleasing to the lover.

She disputes the romantic tradition that love should be a purely altruistic passion, and the testing game of “Would you still love me if I were (poor, ugly, crippled…)?”

We love people for qualities they have which are pleasing to us. […]

It is not intrinsically degrading for women to want men; it has been degrading only because in the past men have not had to bother much about how pleasing they were to women, while women have had to go all out to please men even to survive. In a position of equal dependence and independence between men and women it would not be in the least degrading for either to want, and try to please, the other.

Discussing sensual pleasure, she explores the notion of women as sex objects.

If the aim of the deliberately unadorned feminist is to make sure that men who have the wrong attitude to women have no interest in her, she is likely to succeed.

The best-judging man alive, confronted with two women identical in all matters of the soul but not equal in beauty, could hardly help choosing the beautiful one. Whatever anyone’s set of priorities, the pleasing in all respects must be preferable to the pleasing in only some, and this means that any feminist who makes herself unattractive must deter not only the men who would have valued her only for her less important aspects, but many of the others too.

She argues against the notion that “if you do not care at all about people’s beauty you are morally superior to someone who does”. Those holding such a view

must also think it is bad to care about beauty at all, since beauty is the same sort of thing whether it is in paintings, sunsets, or people, and someone who does not care about beauty in people is someone who simply does not care about beauty.

(I suspect this needs elaborating. People often have blind spots about particular areas of aesthetics: not all of those who admire sunsets appreciate painting, a film buff may not have a taste for interior design, and so on. I’m sure she can clarify my doubt here!)

Now of course beauty is often a low priority, and it is morally good to care relatively little about it when people are hungry, or unjustly treated, or unhappy in other ways. [….] It is not actually wicked to be aesthetically insensitive, but neither is it a virtue, any more than being tone deaf, or not feeling the cold, or having no interest in philosophy or football.

As to sex,

If sensual pleasing is a good thing, why not wear pretty clothes? Why not, in suitable circumstances, dress in ways that are deliberately sexy? […] To refuse to do that may show that you are not interested in men who are interested in sex, but that is a personal preference, and nothing to do with feminist ideals.

Although it may be morally good to give up sensual pleasure to achieve some other end, there is nothing to be said for giving it up unless there is some other end to achieve.

Discussing packaging and degradation, she takes issue with “natural beauty”.

The question of how much effort is worth putting into beauty has nothing to do with feminism. It tends to look like a feminist matter, of course, because it is generally accepted that women make themselves beautiful for men while men go to no such trouble for women, but the idea that this has anything to do with women’s not caring about beauty in men is a most extraordinary myth. They have not, of course, generally been able to demand it. […]

It is the asymmetry of power that is the feminist question.

Anyone who wants a puritanical movement should call it that, and not cause trouble for feminism by trying to suggest that the two are the same.

The chapter moves on to issues relating to sex work—and incidentally suggests a novel way of regarding pianists:

It is quite clear that we do not in general think that there is anything intrinsically wrong with being interested only in certain aspects of people, pleasing people by means of particular skills, entering competitions against other people of similar skill, or earning an income by the use of particular abilities. For instance, suppose a singer heard a splendid pianist at a concert; he might fantasise about giving concerts with her, with no thought about her which went beyond her musical ability. [She explains “they are implied to be of opposite sex only because of the analogy to be drawn with sexual relationships, and for no other reason.”] He might try to meet her, in the hope that she would be willing to enter into a limited musical relationship, and she might agree. She might also happily play the piano to please people who were not in the least interested in other aspects of her. She might enter competitions. And certainly she would try to earn her living by playing the piano for the entertainment of people who enjoyed listening to music. […]

Why should it be acceptable to be paid for charming people’s ears with beautiful sounds, but not for delighting men’s fancies with strip shows and prostitution?

It is said that these things degrade women, and at present they certainly do. However, there is quite enough degradation in the surrounding circumstances to account for women’s being degraded, without having to resort to the idea that there is something bad about unsanctioned or commercially motivated sex. Women are degraded by these things because of the public contempt they suffer, because of the fact that they have to take these activities up whether they want to or not when there is no other way to make a living, and worst of all because once they have sunk to this level they must suffer endless degradations which result from their weak position. […] However, other things, like teaching and manual work, have been made degrading by social attitudes, and in cases like that we have tried to remove the degradation rather than persuade people not to do the work. […]

Sex is said to be cheapened by money. Why should it be, however? Nursing care is a thing which is often given for love, but we don’t think nurses cheapen themselves or the profession when they earn their living by it; we think it is an excellent thing that these people should be able to use their skills all the time, and care for more than just their families and friends.

She struggles to adduce reasons why sex is inherently so different.

The real feminist problem is the unfairness of the present bargaining situation, and the fact that women are in a position to be exploited, and degraded in that way. That certainly has to be attacked with full feminist force.

At the heart of the problem is that “many men do not treat women properly”. And she considers the issue of women’s culture;

the fact that interests and cultures grew under conditions of confinement does not make them less the real culture of that group.

Doubtless women making themselves “deliberately unattractive” was an issue at the time. But she also broaches the important question, “why does everyone presume that the beautification of women is all for men?”, and indeed, later generations have worked this one out. I imagine some younger feminists would wish to further unpack her arguments here about the nature of beauty and attractiveness, and their basis in the male gaze.

Chapter 8, “Society and the fertile woman”, discusses the issues of whether contraception and abortion should be allowed, and whether they should be free. The lengthy section on abortion is all the more relevant today with the shameful reversal of Roe vs. Wade. Chapter 9, “Society and the mother”, explores arrangements for childcare, and whether the state or parents should pay for it.

Chapter 10, “The unpersuaded”, returns to the problem that, despite the strength of the feminist case, the movement was still broadly unpopular. Pondering remedies for this situation, she discusses three issues in turn: that there is no reasonable feminist case at all; that it is exaggerated; and that the image of the movement is unattractive. She responds cogently to a series of objections.

The greatest possible care must be taken not to make the uphill grind even worse than it need be, through the careless presentation of a feminist image and feminist policies which drive the movement’s natural supports back into the traditional camp. If a more careful formulation of radical feminist policies will lead not only to a better plan for the future, but also to a kind of radical feminism which is attractive and understandable to the people who are at present its opponents, then no feminists—least of all the ones who feel that reason has no place in political achievement—can afford to be careless in argument. The very impossibility of reaching most of the unpersuaded by the force of reason becomes the final demonstration of the indispensability of care in argument amongst feminists themselves.

* * *

The 1994 edition has two further Appendices clarifying and augmenting her arguments. And in her new Introduction she reflects on reactions to the book, and acknowledges that the book displays “period features”; but while many once-controversial campaigns had been won (and other issues were becoming prominent, such as LGBT rights and pornography), most of the questions she confronts remained apposite. In the public forum, she notes, a change of rhetoric need not always imply a change of substance.

Today, as feminists deplore “the return of sexism” (Natasha Walter, Living dolls), many arguments revolve around mundane issues for women such as merely staying alive, let alone retaining control over their own bodies or achieving equal pay.

But after all these years, with so many feminist authors building on the work of previous generations (in Britain, an outstanding instance is Laura Barton’s Everyday Sexism campaign; and cf. the succinct, accessible manifestos of Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche), these issues remain highly apposite—not least the reluctance of some women (and indeed men) to identify as feminists.

Sadly, Janet Radcliffe Richards’ philosophical pursuits haven’t resulted in further publications on feminism—but her three lectures from 2017 on “Sex in a shifting landscape” start here. I’d also love to see her sinking her philosophical teeth into PC gone mad, and Brexit.

See also Gender: a roundup, including Words and women, Sexual politics, The handmaid’s tale, and for a suitable playlist, You don’t own me. For an introduction to gender and music, see under Flamenco 2: gender, politics, wine, deviance.

.

Manji again returns to an earlier story, that of

Manji again returns to an earlier story, that of

Rather than rejoicing in Sanna Marin’s humanity, some people have queried her “lapse of judgment”. Apparently what disturbs them is that she is seriously cool. Oh well, good to know that even in Scandinavia there are some puritanical fuckwits. It also reminds me strongly of the faux outrage over the video of

Rather than rejoicing in Sanna Marin’s humanity, some people have queried her “lapse of judgment”. Apparently what disturbs them is that she is seriously cool. Oh well, good to know that even in Scandinavia there are some puritanical fuckwits. It also reminds me strongly of the faux outrage over the video of

* Dry Summer was the debut role of

* Dry Summer was the debut role of

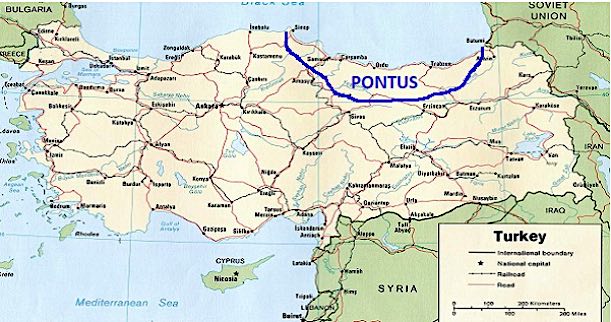

Matzouka, Trebzon, 1950s (

Matzouka, Trebzon, 1950s (

Not the new European champions defending a corner (another

Not the new European champions defending a corner (another  Photo: BBC.

Photo: BBC.

As

As