Back from Istanbul in time for the “late-night” * Bach Prom with Iestyn Davies and the English Concert directed by Kristian Bezuidenhout from the harpsichord.

Listen here!!!

Between the typical Proms fare of monumental romantic symphonies, the Royal Albert Hall also make a wonderful setting to tune in to the more intimate sound-world of early music—even Bach’s suites for unaccompanied violin and cello have featured in the large hall.

The ensemble projects a classy image, with Iestyn Davies occupying his own niche in the counter-tenor superstar gallery carved by singers such as Alfred Deller, Michael Chance, and Andreas Scholl. Kristian Bezuidenhout, a versatile early keyboard specialist, is clearly supportive of the band’s creativity. The upper strings stood to play, adding another layer of communicative energy.

I’m always fascinated to imagine the original Leipzig congregation, steeped in Lutheranism—Bach’s new music must have amazed them every week. By contrast, today our sound-world is infinitely more diverse (and secular), subsuming Mahler, film music, rock, and ringtones; and the way we rejoice in Bach is quite different too.

The programme notes cite an 1898 review of a Bach Prom, praising music that was probably “new for the very large majority of those present, for it is doubtful if it had ever been played before in the metropolis”.

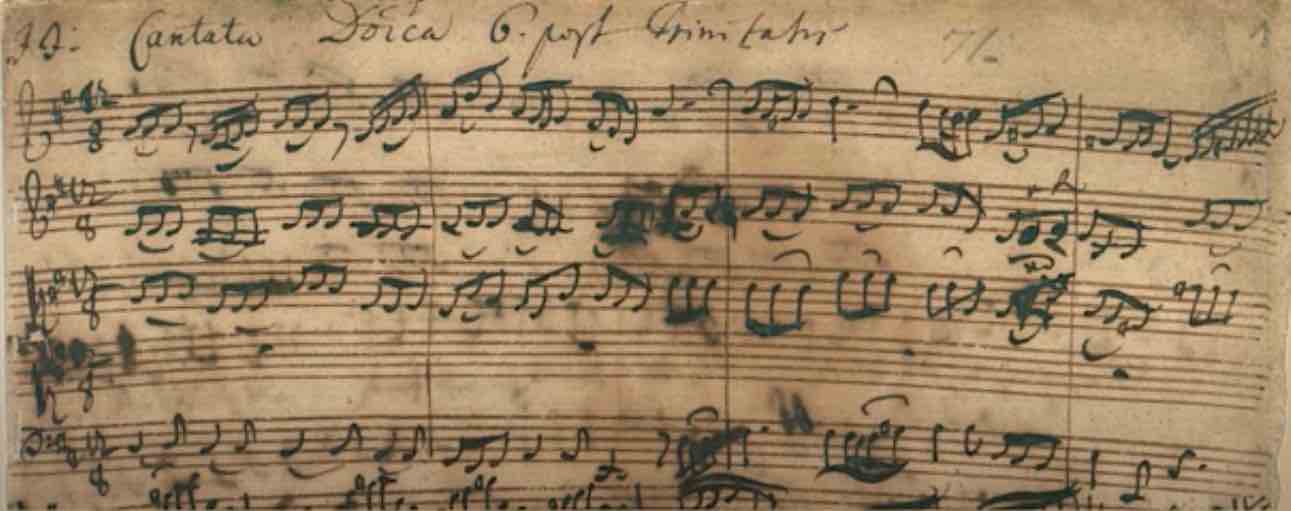

The intensity of the occasion was enhanced by Davies singing without a score—Bach’s own counter-tenor (clearly outstanding, though we don’t know who he was) must have used one, having only got hold of it a few days earlier, with the copyist’s ink barely dry. The music was entirely new to performers and audience—and they would be lucky if they ever heard it again, whereas today both performers and audience can also listen to a range of recordings. Tom Foster relished Bach’s solo organ writing, while oboes enriched the string sound.

The group played two cantatas first performed in Leipzig in 1726:

- Cantata 170, Vergnügte Ruh, beliebte Seelenlust (Bach cantatas site, and wiki), for the sixth Sunday after Trinity (for those of us who keep track of seasonal rituals), “longing for a virtuous death as a release from the world’s swarming violence and death”.

The cantata plunges us right into a magical world—John Eliot Gardiner’s thoughts on Bach are always insightful (notes here):

The opening aria is pure enchantment, a warm, luxuriant dance in 6/8 [?!] in D. You can almost feel Bach’s benign smile hovering over this music, an evocation of Himmelseintracht, “the harmony of heaven”. One of those ineffable Bach melodies that lodges itself in one’s aural memory, it takes a whole bar to get going but once launched, seems as though it will never stop (actually it is only eight bars long, but the effect is never-ending). Yet this expansive melody given to oboe d’amore and first violin acquires its beauty and its mood of pastoral serenity only as a consequence of its harmonic underpinning. The gently lapping quavers in the lower strings are slurred in threes, suggestive of “bow vibrato”, or what the French referred to as balancement, while the downward-tending bass line sounds as if it might be the first statement of a “ground”—in other words, the beginning of a pattern that will repeat itself as though in a loop. Well, it does recur, but not strictly or altogether predictably. With Lehms’ text in front of him, Bach is searching for ways to insist on spiritual peace as the goal of life, and for patterns that will allow him to make passing references to sin and physical frailty.

Here Gardiner accompanies Michael Chance in the first and final arias:

The slow aria Wie jammern mich doch die verkehrten Herzen with organ, is another miracle—the lack of continuo “symbolic of the lack of direction in the lives of those who ignore the word of God”. The violins and violas play a middle-register line in in unison—Gardiner again:

This special texture, known as bassettchen, is one that we have encountered on a number of occasions this year when Bach decides that a special mood needs to be created and removes the traditional support of basso continuo. He uses it symbolically in reference to Jesus (someone not requiring “support”), protecting the faithful from the consequences of sin (as in Aus Liebe, the soprano aria from the St Matthew Passion), and at the other extreme to serial offenders, as in that other marvellous soprano aria, Wir zittern und wanken from BWV105, or (as here) to those “perverted hearts” who have (literally) lost the ground under their feet in their rejection of God. The aria is written from the standpoint of a passive witness to the “Satanic scheming” of the backsliders as they “rejoice in revenge and hate”, so that one can sense the observing singer’s anxiety in the fragmented rhythm of the bassettchen line.

Here’s the complete cantata with Gustav Leonhardt and Paul Esswood in 1985:

Just as astounding is

- Cantata 35, Geist und Seele wird verwirret (“Spirit and soul become confused”: Bach cantatas site, and wiki), for the twelfth Sunday after Trinity, six weeks later!

Léonard Gaultier, Christ healing a deaf man (1579).

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

In two parts, to be performed before and after the sermon, the Gospel for the day was St Mark’s account of Jesus curing a deaf mute (cf. my stammering series—where’s Jesus when you need him, eh?). Again with obbligato organ and oboes, the cantata expresses both the “sorrow-laden yoke of pain” and a sense of celebration. Here’s Gardiner during the 2000 Bach Cantata Pilgrimage (notes here):

Between the two cantatas, the third Brandenburg concerto was exhilarating—like the Duke Ellington band, as I keep saying. How ungrateful was Bach’s patron!

All Bach cantatas are miraculous—for more, see The ritual calendar, and other posts in my Bach series; see also Bach and the oboe. For meretricious, woke, yet fascinating speculations on the colour scheme of early keyboards, see Black and white.

* In the sense of befuddled octogenarians nodding off over a cup of Ovaltine. I mean, 10.15 is a perfectly normal starting time for a regular evening concert in Andalucia…

Transcription by Diego Carpitella.

Transcription by Diego Carpitella.

Among all the

Among all the