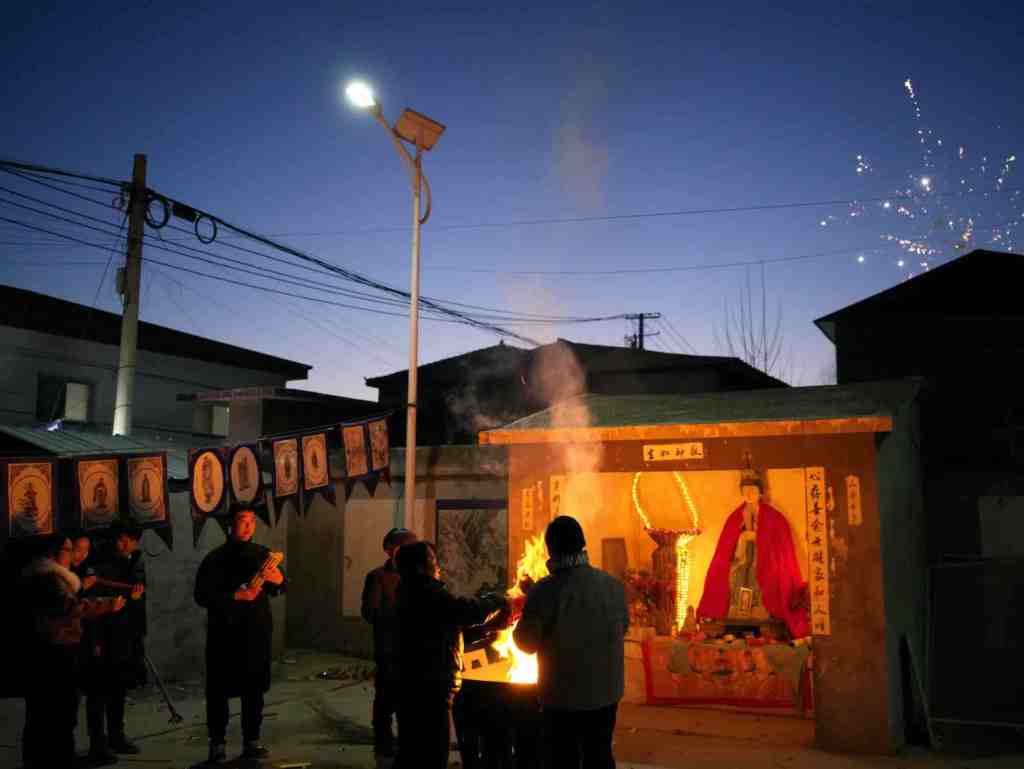

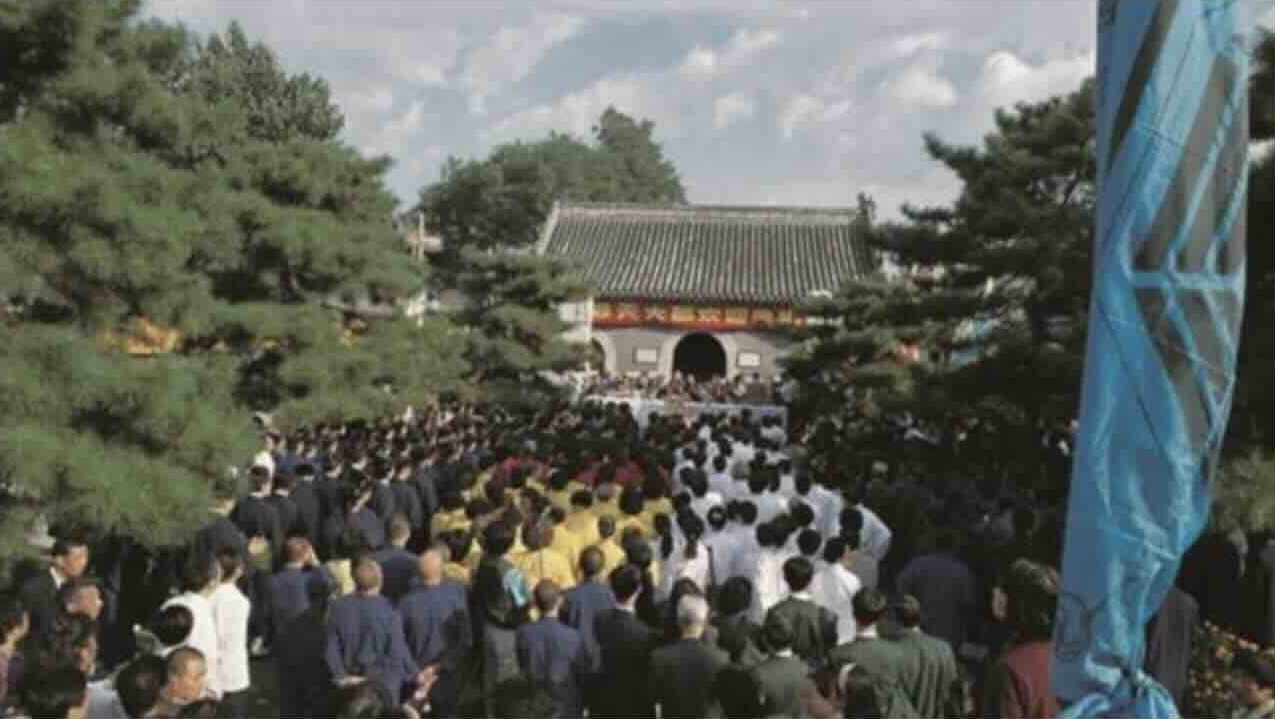

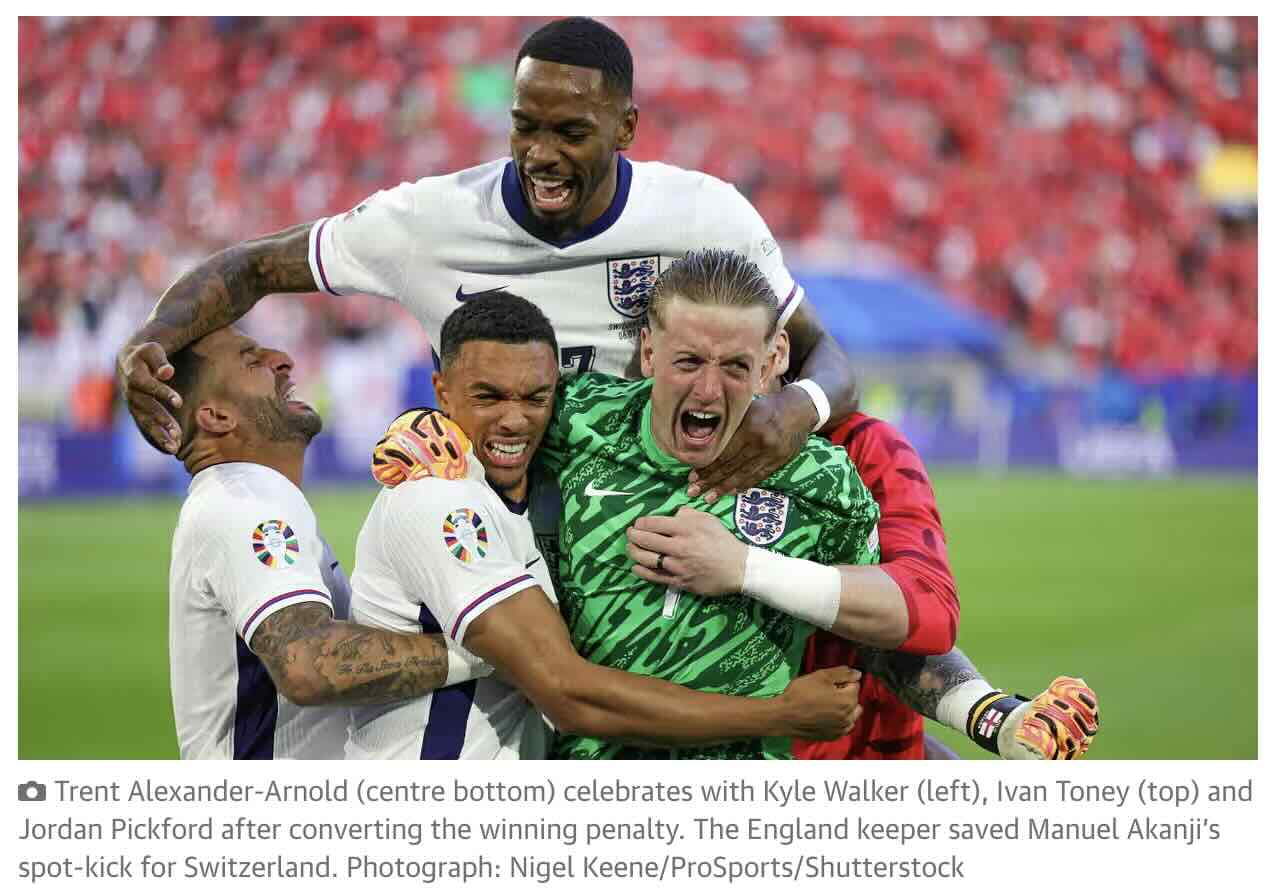

The Li family Daoists perform the Pardon ritual at village funeral, Yanggao 1991.

The Li family Daoists perform the Pardon ritual at village funeral, Yanggao 1991.

My first visit to Yanggao in 1991 began an enduring relationship with the Li family Daoists and other ritual specialists of the otherwise unprepossessing county in north Shanxi. The great Li Qing (1926–99) was the seventh generation of household Daoists in the lineage, his son Li Manshan the eighth (besides my film and book, posts are rounded up here, including More Daoists of Yanggao, and Yanggao personalities).

Earlier this year I wrote about the venerable Buddhist monk Miao Jiang, also born in Yanggao. Now, thanks to Yves Menheere, I’m intrigued to learn of another native of the county: Li Wencheng 李文成 (no relation to our Daoist lineage!), an “old revolutionary” who miraculously became General Secretary of the Chinese Daoist Association in his 60s. He has just died at the age of 97, prompting nationwide memorial ceremonies (clearly secular services!).

Focused on the PRC, the Bitter Winter website’s coverage of (abuses of) religious liberty and human rights is important, even if I sometimes quibble with its stance (such as here). To augment its obituary of Li Wencheng I’ve gone back to the (selectively) detailed interview by the Chinese Daoist Association in 2021 (and this shorter eulogy, even more conformist). Bitter Winter is indeed frosty:

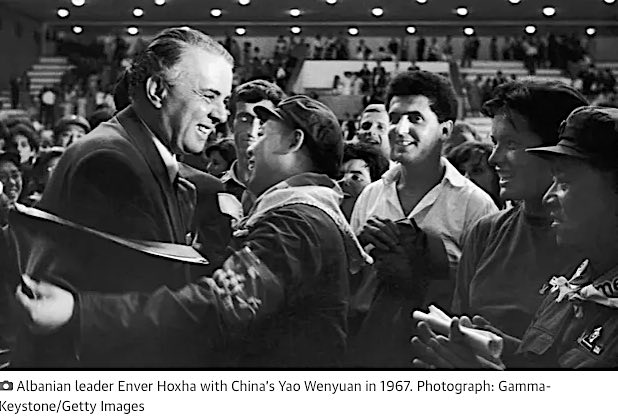

The former General Secretary of the Chinese Daoist Association knew nothing about religion but was made by the CCP first into a Catholic and then a Daoist leader. […] Li was a crucial figure in the history of government-controlled Daoism. His life and career shed a light on how the CCP selects the personnel it calls to lead the country’s religious organisations.

There can be no doubt about the subservience of state religious departments to the Party. Normally I would give short shrift to such high-ranking apparatchiks; while CCP religious policy is a perfectly valid research topic, it may obscure grassroots practice. Since Li Wencheng’s life makes an intriguing contrast with those of my Daoist masters in the county, here I will intersperse his story with that of the Li family Daoists on the eve of Liberation, under Maoism, and since the 1980s’ reforms (again, covered in my book and film); as well as with that of the eminent Miao Jiang. Despite my own aversion to officialdom, my interpretation will be rather less polemical than that of Bitter Winter.

* * *

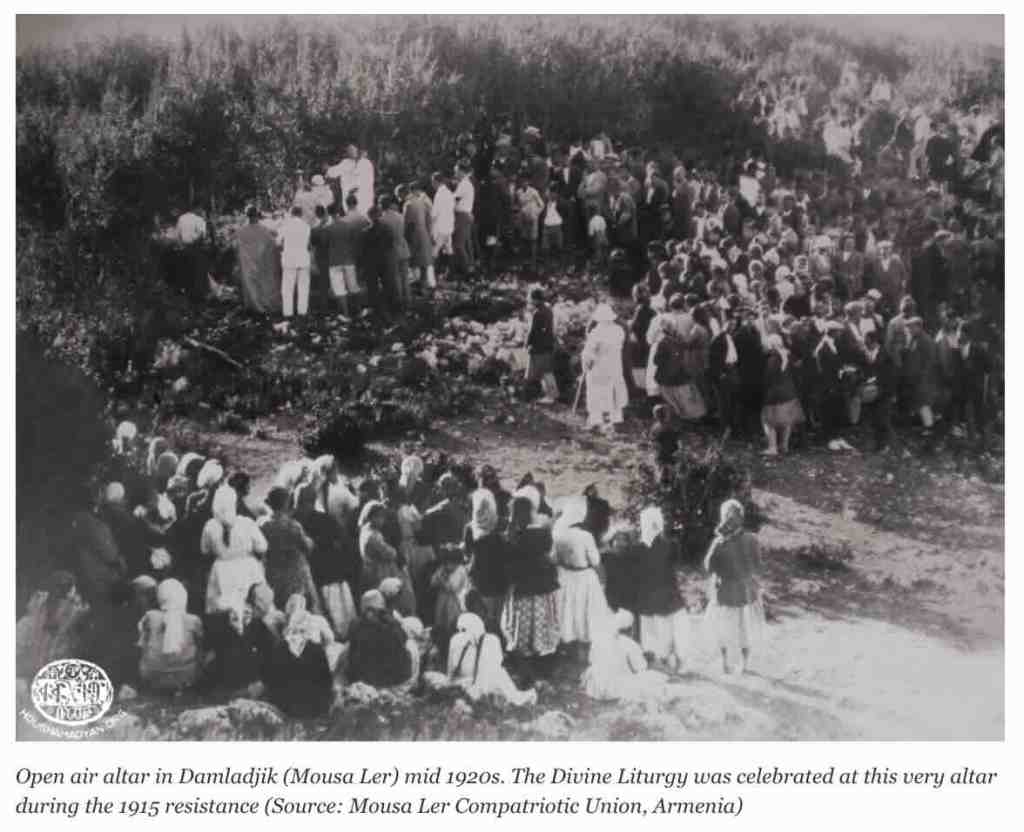

With my field experience in Gaoluo, I was keen to document the early years of revolution on the plain just south of Yanggao county-town (for the disparity between my fieldwork methods in the two sites, see here). But I never found any “old revolutionaries” there who could describe the period in detail.

One could hardly expect upright cadres like Li Wencheng to volunteer frank reminiscences of the events surrounding the trauma of land reform. But his account makes a rather more personal supplement to that of the 1993 Yanggao county gazetteer. [1]

Some sites in the partial overlap between Li Wencheng’s war years and

(in red) household Daoist bases. Cf. map here.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng was born in Gucheng village in 1927, the year after the great Li Qing. From July 1945, just before the surrender of the Japanese invaders, he “engaged in revolutionary activities” further south in Yanggao, joining the motley armed militia of 2nd district, a mere couple of dozen men. The militia was soon disbanded, whereupon he was transferred to the county lianshe 联社 association (forerunner of the gongxiaoshe Supply and Marketing Cooperatives). He gained admission to the CCP in March 1946.

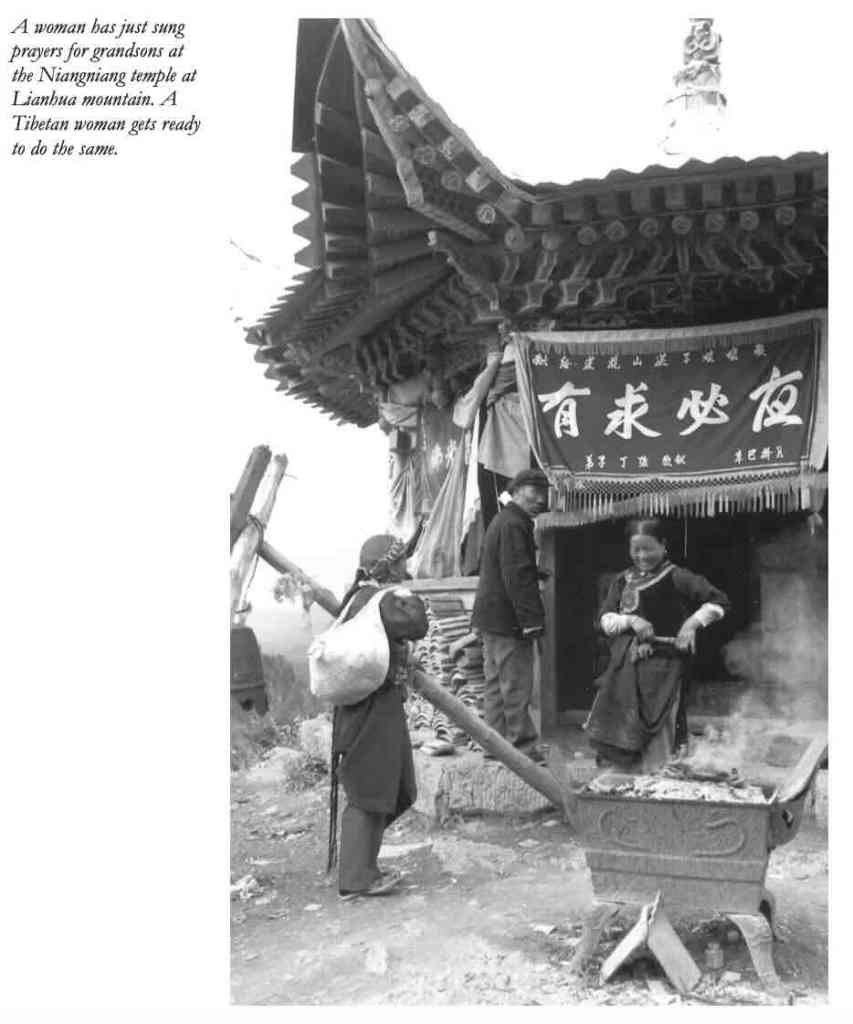

Ritual life in Yanggao had persisted even under Japanese occupation. A 1942 stele commemorating the Zhouguantun temple fair lists the names of five Daoists from the Li family, who dutifully “offered the scriptures”—including Li Qing, then 17 sui. Li Qing recalled, “Our ritual business didn’t suffer during the occupation—the troops, themselves devout, even made donations when they came across us doing Thanking the Earth rituals! The local bandits didn’t interfere either”. He married in early 1945; his son Li Manshan was born in 1946. Li Qing’s Daoist father Li Peixing was shot dead accidentally by Nationalist troops in 1947.

After the Japanese surrender the Communists briefly took over Yanggao town, but by autumn 1946 Li Wencheng joined them in retreating south to the hills to engage in guerilla activity when Fu Zuoyi’s forces occupied the area. Fording the Sanggan river, they traversed the mountains of Guangling and Lingqiu counties to reach safety in Fanshi. Though travelling in only two trucks, they had to take cover from bombings by KMT planes. In Fanshi Li Wencheng took part in the initial stages of land reform, training for three months in Hunyuan county-town, base of the North Shanxi district committee.

All these counties also had active groups of household Daoists, intermittently serving the ritual needs of their local communities (Guangling, Hunyuan, as well as the household Buddhists of Fanshi).

Li Wencheng’s first mission to implement land reform was doomed to failure, sent all alone to a mountain village on the very southern border of Yanggao county. In December 1947, while still involved in guerilla warfare, he was deployed to Yanggao 1st district, serving as financial assistant (cailiang zhuli 财粮助理) for the imposition of land reform in Upper village (Shangbu 上堡) just north of Dongjingji.

The CCP county administration had moved south of the Sanggan river, but the district base was just south of Gucheng at Dongxiaocun, a large village of over a thousand households, its Upper Fort (where they set up) towering over the Lower Fort. But it was sandwiched nervously in between the KMT strongholds of East Jingji township, just 20 Chinese li (10 km) east, and Xubu to the west. The guerillas often had to flee from KMT cavalry raids.

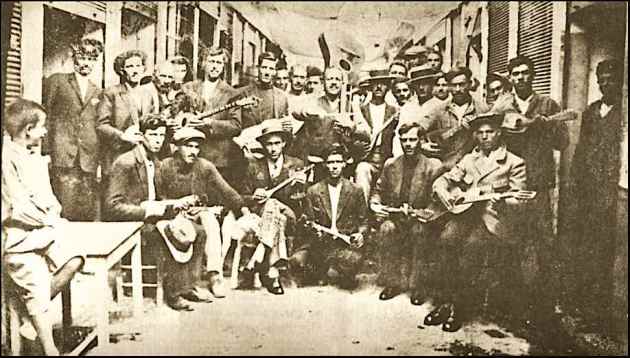

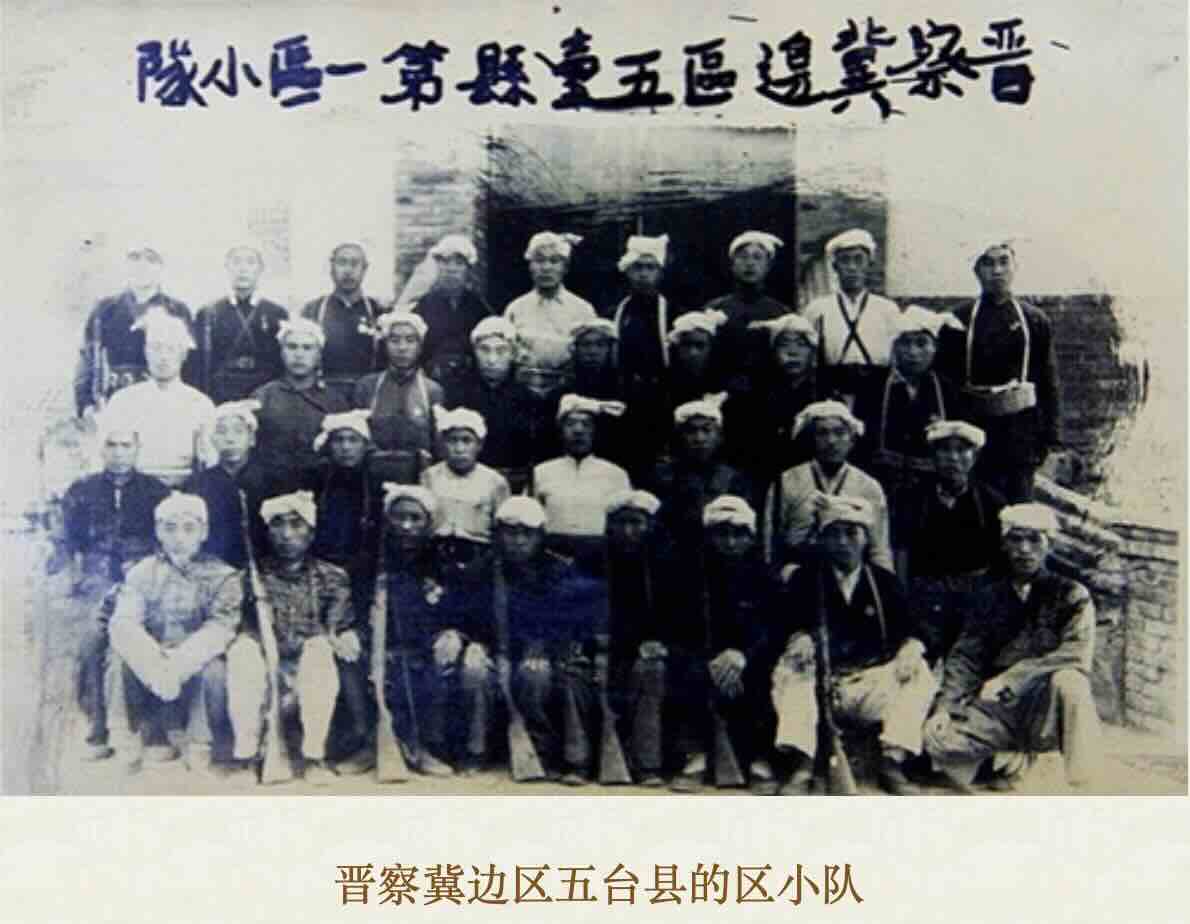

Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei frontier zone, Wutai county 1st district “small team” militia. Source.

Note the headscarves, archetypal emblem of the revolution.

By 1948 the Communists could look forward to victory, and the Party government was able to move back to Yanggao town. In the autumn, with Yanggao already “liberated”, Li Wencheng was sent to “support the front line” (zhiqian 支前), providing supplies for the troops around the Sanggan river, Fengzhen and Jining further north, and Zhangjiakou.

Li Peisen and his wife Yang Qinghua, late 1940s?

In 1947 in Upper Liangyuan, household Daoist Li Peisen, former village chief, perhaps realising that land reform was imminent, quietly moved his family to his wife’s natal village of Yang Pagoda in the hills just south, taking his sets of ritual instruments and costumes, as well as two trunks full of scriptures handed down in his branch of the lineage. People from “black” families tended to encounter less scrutiny outside their home village. The family of Li Peisen’s wife were well-off and well connected; both he and his wife are remembered as highly intelligent. Their move was clearly an astute way of sidestepping any investigations into his background—his economic standing, and his connections with the vilified Japanese and Nationalists. Yang Pagoda might make a safer base from which to survey the lie of the land under the new regime—the potential sensitivity of practicing ritual would have been a minor issue.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Anyway, Li Peisen wasted no time in displaying his political correctness. Amazingly, he now gains an honorable mention in the county gazetteer. In March 1949—just as family members back in Upper Liangyuan were being stigmatised with a “rich peasant” label—he was the very first in the whole county to organise a mutual aid co-op, consisting of three households. Li Peisen’s move to this tranquil village, and his wife’s careful assertion of local status, were to play a major role in enabling the lineage to preserve its Daoist traditions.

Most of the household Daoist traditions in Yanggao county were based on the plain just south of the county-town; in the hills further south in the county, such groups seem to have been quite few even before the 1950s (I listed some groups in my book, p.63).

Under Maoism

From early 1949 Li Wencheng took up a series of administrative posts in Yanggao, then part of Chahar province, serving as secretary of county and regional propaganda departments. In 1950 he married Zeng Hua in Yanggao town. She came from East Chang’an bu village, just southwest of Upper Liangyuan. Their three children went on to find work further afield, whereas Li Wencheng’s four siblings continued tilling the land in Yanggao.

By 1952 Li was assistant editor of the financial team of the Chahar Daily, but later that year Chahar province was abolished and he was transferred to Beijing with over twenty other journalists, where they found themselves under-employed. With two others he was soon selected for the Religious Affairs Department of the Cultural and Educational Committee of the State Council. For six months in 1954 he was trained in “religious history, religious policies, and the domestic and foreign religious situation”. He then took part in a study class for Catholic clergy in the Church of the Saviour (Xishiku) in Beijing, along with over a hundred priests and bishops. As he recalled, they mainly studied patriotism and anti-imperialism, on the basis of articles opposing religion by Fang Zhimin 方志敏, a Red Army military commander executed by the KMT in 1935. Whatever the truth of the incident leading to Fang’s execution, [2] this hardly made a promising introduction to the subject. Li Wencheng now worked loyally for the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association and the Religious Affairs Bureau. Bitter Winter:

By his own admission, he was a Marxist who knew precious nothing (sic) about religion.

But in contrast to all the detail on the War of Liberation, the interview has a typically glaring lacuna between 1954 and 1984. Through successive political campaigns, even Party loyalists had to be very cautious; serving as a cadre was an unenviable task that could easily lead to labour camp, even before the violence of the Cultural Revolution. The interview doesn’t broach Li Wencheng’s duties in monitoring Catholicism through the 1950s and early 60s—a stressful period. After the arrest and imprisonment in 1955 of Bishop Gong Pinmei along with several hundred priests and Church leaders, the official Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association was founded in 1957, marking a schism with the Vatican, but underground house-churches continued to function. Nor does the article mention Li Wencheng’s experiences during the Cultural Revolution. We may never learn the story of how he weathered the period.

The Catholic church, Gaoluo (just south of Beijing)—built in 1931, destroyed in 1966.

The village’s Catholic families maintained their faith through the decades of Maoism,

reviving since the 1980s but still resistant to the “Patriotic Church”.

Back in rural Yanggao, Miao Jiang (b.1953) came from a devout Buddhist family in West Yaoquan village, somehow maintaining his faith through campaigns, having his head shaved in Datong to become a monk at the extraordinary time of 1968.

While the Li family Daoists kept performing after Liberation, encroaching collectivisation led to ever more desperate poverty, and by 1958 Li Qing was happy to take a state job in the North Shanxi Arts Work Troupe based in Datong city, even though their tours of the countryside were tough. He returned home when the troupe was cut back in 1962, after the worst of the famine. Despite a brief revival, Daoist ritual was silenced by 1964, and through the Cultural Revolution the Li family lived in fear, vulnerable by virtue of their “black” class background.

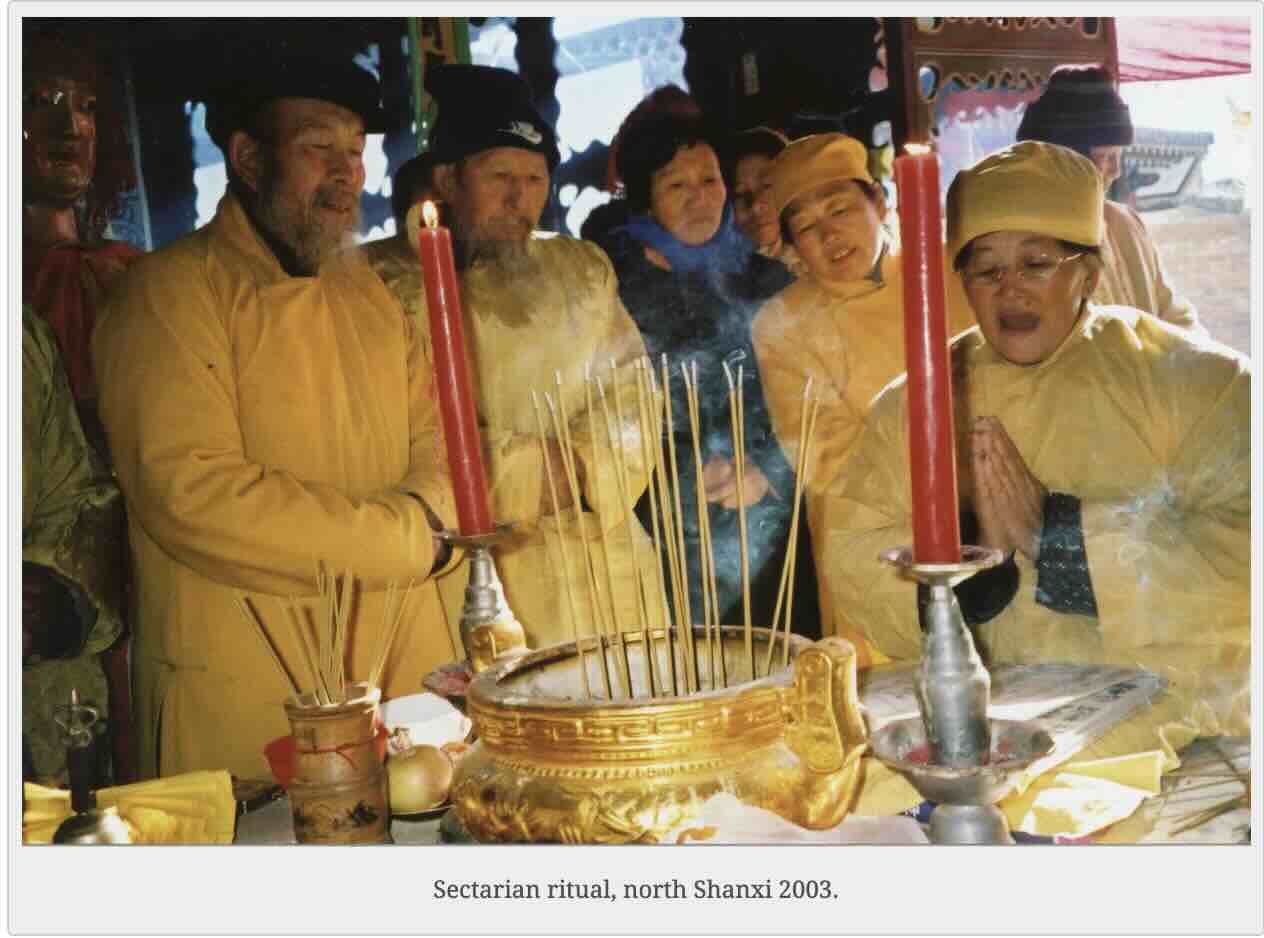

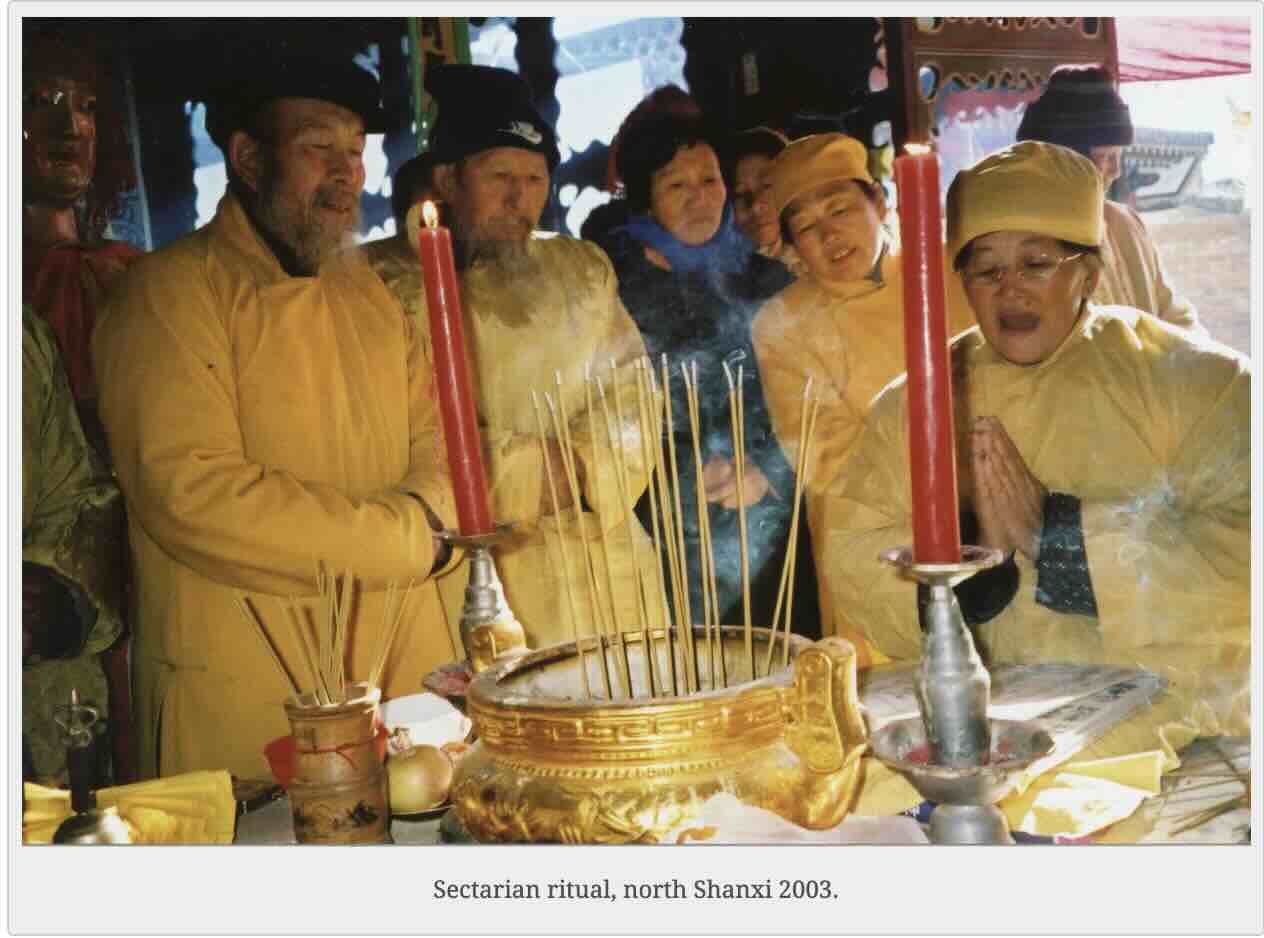

Even less palatable for a Party stalwart like Li Wencheng would be sectarians and spirit mediums, many of whom somehow maintained clandestine activity under Maoism despite campaigns to suppress them soon after Liberation. In Yanggao, village adherents of the Bright Association (Minghui) and Yellow Association (Huanghui) recited lengthy “precious scrolls” as part of rituals for their own followers; the leader of one such group even transmitted the liturgy to his teenage son early in the Cultural Revolution. Since the death of Mao and the downfall of the Gang of Four, both sectarians and mediums revived, broadly tolerated by the local authorities.

Since the reforms

Miao Jiang has been based at the Buddhist mountain complex of Wutaishan since 1980, as the mountain opened up to a massive reinvigoration of “incense fire”after the depression of the Maoist era. His devotion to restoring temple life there was soon recognised as he was fêted with official titles.

But in utter contrast to Li Wencheng, he has remained aloof from worldly affairs: his allegiance has always been to the dharma, and any organisational responsibilities grew out of his faith. Eschewing the lifestyle of official banquets, he adheres to a simple Buddhist diet, while sponsoring charitable and relief projects. Still, religion needs organisers…

The Li family Daoists had begun to resume activity from around 1980 (see Testing the waters, and Recopying ritual manuals), and were soon busy “responding for household rituals”. In autumn that year, Li Manshan took his first train trip to Beijing, with his cousin Li Xishan. They wanted to buy a sewing machine, not available (or at least substandard) in Datong, but in the end they couldn’t find a good one in Beijing either—so Li Manshan bought a big bag of socks instead.

As Li Wencheng recalled, as he approached his 60th birthday he was expected to retire. But somehow in 1986 he was chosen to serve as General Secretary of the Chinese Taoist Association. Though at first reluctant, being in good health he was happy to keep working. He stayed in the post for thirteen years until retiring in 1999.

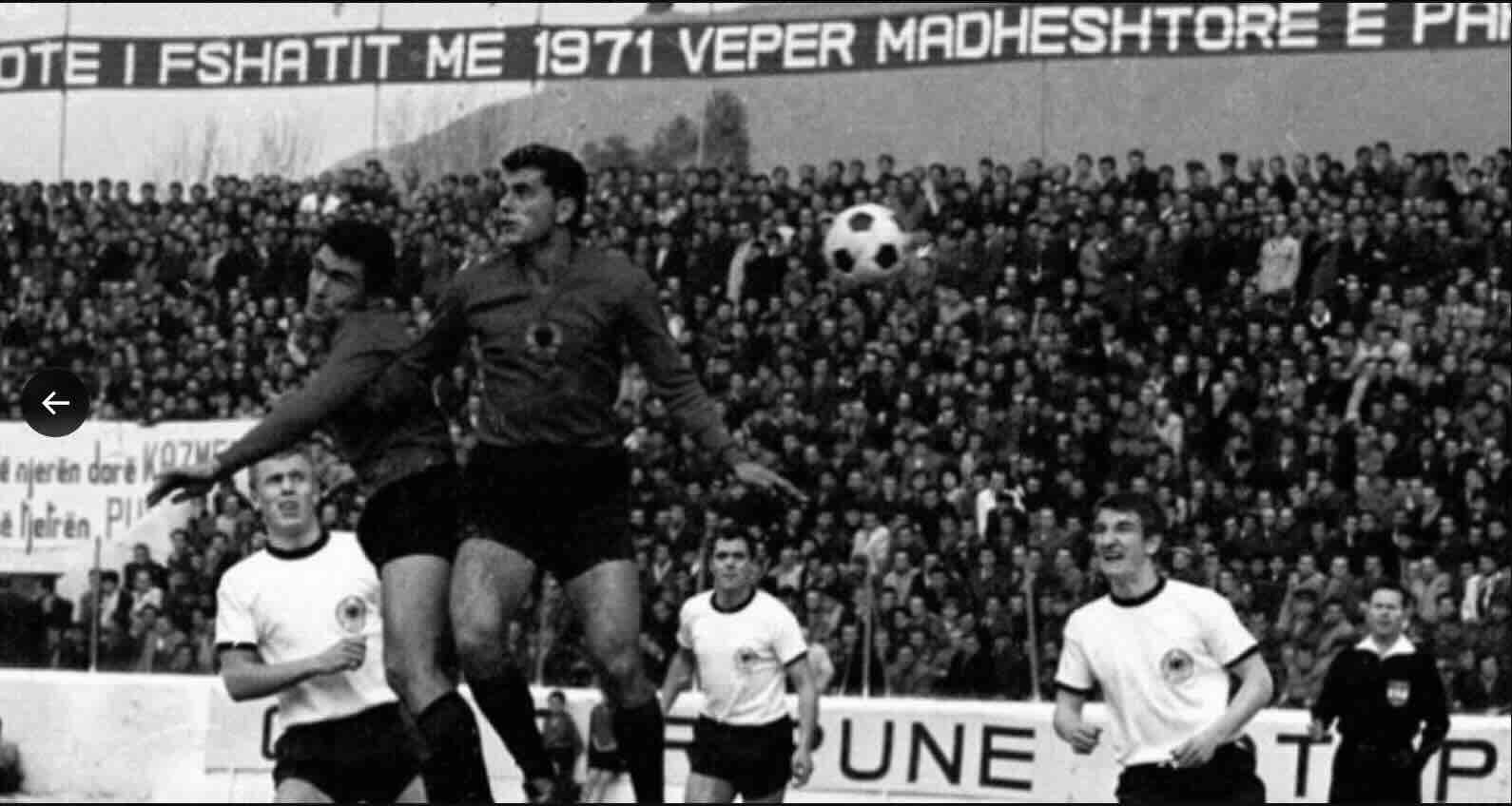

Fourth conference of the Chinese Daoist Association, 1986. Source.

Through his early years around Yanggao, first as guerilla, then as cadre, Li Wencheng can hardly have had any contact with folk ritual activity—and like his comrades, had he chanced upon it, he would surely have disdained it. Once on the Party ladder in Beijing the only experience he gained of religion was overseeing CCP policy towards Catholicism. While many devout and prestigious Daoist and Buddhist clerics were recruited to official religious bodies after Liberation, they were often “mobilised” (coerced) as figureheads.

Li Wencheng now found himself responsible for state policy towards Daoism at a time of a spectacular religious revival (for a fine study of the grassroots revival in Fujian, click here). He helped found the Chinese Daoist Academy and the magazine Zhongguo Daojiao, mouthpiece of Party policy; he re-established the system of ordination in Beijing and elsewhere, working with Wang Lixian 王理仙, respected abbot of the Eight Immortals temple in Xi’an. But he doesn’t mention the great Min Zhiting, who was also summoned to the White Cloud Temple around this time (cf. Zhang Minggui, abbot of the White Cloud Temple in Shaanbei, whose efforts to maintain worship on the mountain ever since the 1940s have always involved negotiating local politics).

In 1990 Li Qing led a group of his Daoist colleagues to perform at a major festival of Buddhist and Daoist music in Beijing. The Li family Daoists were lodged in the White Cloud Temple along with several other Daoist groups from elsewhere in China invited for the festival, doing five performances (not rituals) for private invited audiences over fifteen days in the temple and at the Heavenly Altar. Some apparatchiks were opposed to the event, but influential senior ideologues like He Jingzhi and Zhao Puchu supported it. In the end, the Religious Affairs Bureau and the Chinese Daoist Association must have been among the official bodies sponsoring the festival. I wonder if Li Wencheng attended—would he have been curious to encounter Daoists from his old home of Yanggao, or would he have distanced himself from such household ritual specialists?

And I wonder how often he returned to Yanggao to visit his siblings and their children. For funerals there since the late 80s, it has again become routine to hire Daoists to perform rituals—events that Li Wencheng’s relatives would doubtless often attend.

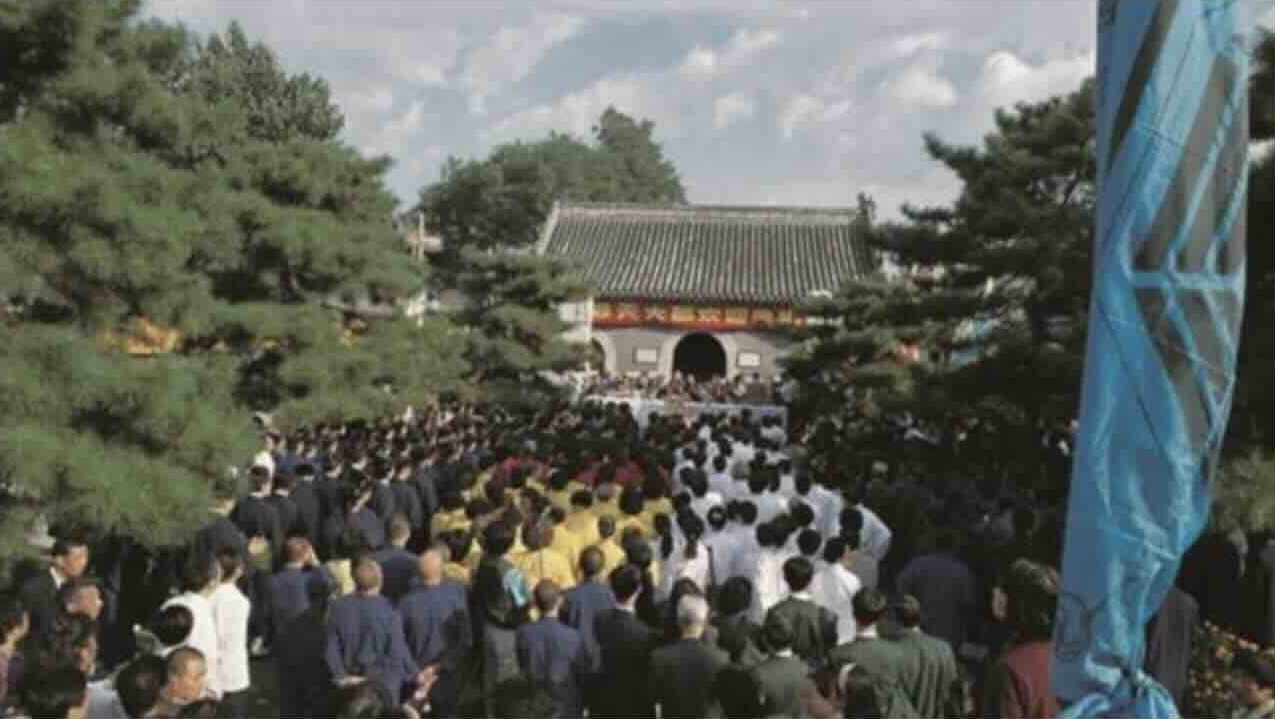

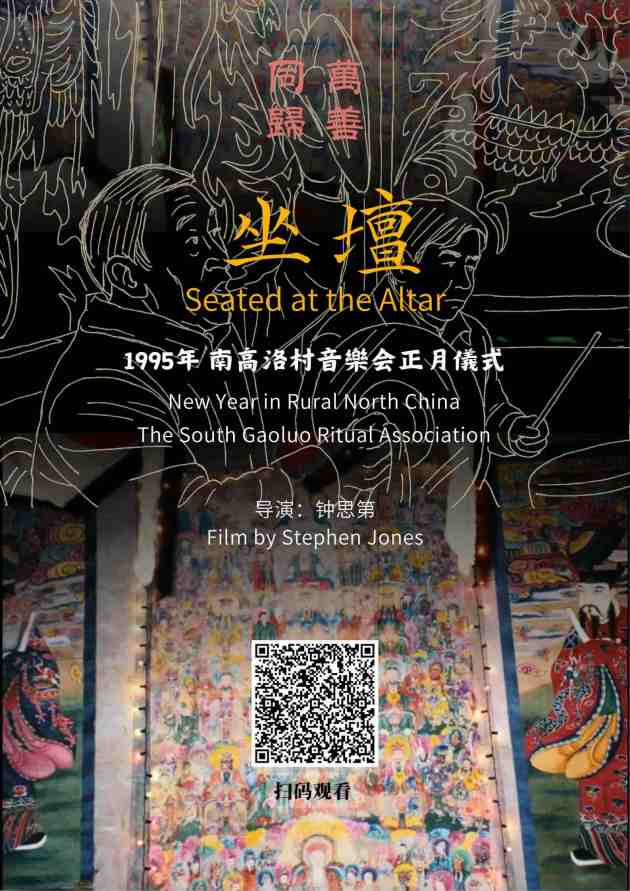

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Source: Weibo.

Another comment in the Bitter Winter article that I find rather too stark: perhaps not exactly that Li Wencheng “used Daoism to spread CCP propaganda in Hong Kong and Taiwan”, rather that Daoism could indeed make a useful tool to further diplomatic rapprochement. To this end a significant step in 1993 was his organising of a Great Open-air Offering (Luotian dajiao 罗天大醮) ritual at the White Cloud Temple, bringing together Daoist priests from temples around the PRC—with representatives from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Clips can be found online, such as this by the Daoists of the Xuanmiao guan temple in Suzhou.

In 2015, for the 70th anniversary of victory in the War of Resistance against Japan,

Huang Xinyang (left), Deputy Chief of the Chinese Daoist Association,

presented Li Wencheng with a commemorative medal. Source.

2018: Li Manshan with Shi Shengbao (b.1948), ritual director of Yangguantun village, Yanggao.

* * *

Li Wencheng’s responsibility in later life for marshalling CCP policy towards Daoism was quite serendipitous. Bitter winter again:

What is most interesting in this biography is that Li changed religions as others change shirts. He was first non-religious, then Catholic, then Daoist.

Interesting indeed, but the comment is somewhat misleading. Li Wencheng was surely never “religious”, and his task of monitoring Catholicism and then Daoism didn’t imply “belief”, any more than it does for ethnographers of religion; no conversion was involved (and anyway, Buddhist and Daoist deities can happily coexist in folk pantheons!). The article goes on:

This did not really matter since his job was to serve the CCP, not religion. He was sent to different religious organisations to “implement the Party’s religious work policies”. He was a typical example of the bureaucrats the CCP selects for the five authorised religions. Many of them do not believe in God or religion. They are there just to control religion on behalf of the Party.

Most appropriately, the official press release celebrated Li as somebody whose life was “an unremitting struggle for the cause of Communism”—not of Daoism or any other religion.

The Party’s efforts to control temple clerics were extensive, and effective; Buddhism was always based mainly in temples, and temple-dwelling Daoist priests too could be efficiently overseen too. But the life of Daoism depended less on temples, and the countless household Daoists throughout the countryside were harder to control—even if Li Wencheng was doubtless involved in the successive efforts to register them.

* * *

One could find similar grassroots religious activity in the home county of any secular Party apparatchik (all the way up to Chairman Mao and his Hunan origins)—I’ve just given these vignettes from my experience of Yanggao. The Li family Daoists remain busy performing rituals in the nearby villages; Miao Jiang, a devout Buddhist since his early youth, found himself becoming a revered master on Wutaishan; Li Wencheng, who never had any sympathy with religion, somehow ended up overseeing major Daoist projects from his Beijing office.

Conversely, Party overseers often lament cadres’ persistent adherence to “feudal superstition”. At the local level, it is perfectly routine for village cadres to consult household Daoists (like Li Manshan) or spirit mediums to “determine the date” or identify an auspicious site; some such cadres may even be ritual specialists themselves. But cadres higher up the Party ladder too may consult “superstitious practitioners” (e.g. here).

Even among those who were earmarked to represent Party religious policy, we find a range of ideology. Some, like Li Wencheng, were entirely secular in their thinking, their sole mission to serve the Party. Temple priests invariably have to pay lip service to the CCP cause; like the broader population, they are used to compartmentalising public and private spheres. Back in the countryside, “faith” may play a certain role for some household Daoists (such as Jiao Lizhong in Hunyuan) but for others it is a minor issue, compared to the mundane exigency of feeding their families while serving the local community.

As evoked movingly in Tian Zhuangzhuang’s 1993 film The blue kite, everyone was trying to survive, subject to the whims of Party campaigns. Some were able to escape the poverty of rural life by finding an “iron food-bowl” with a Party career, while others remained tied to the land and its rituals. Both were common trajectories. And both the CCP and religious observance, in all their diverse manifestations, are part of the fabric of life in China.

[1] Though I haven’t yet found Li Wencheng’s name in the county gazetteer, it’s a useful source for both the civil war and “revolutionary heroes”, with considerable detail on the period (mainly on pp.15–20 and 50–54), which I haven’t attempted to collate with Li’s own account.

[2] Bitter Winter notes that charges against Fang Zhimin had included the beheading of an American Christian missionary and his wife in 1934—although doubts have been raised whether Fang was directly involved (e.g. here, and here), and even whether the couple’s abduction and execution was among the KMT’s charges against him.

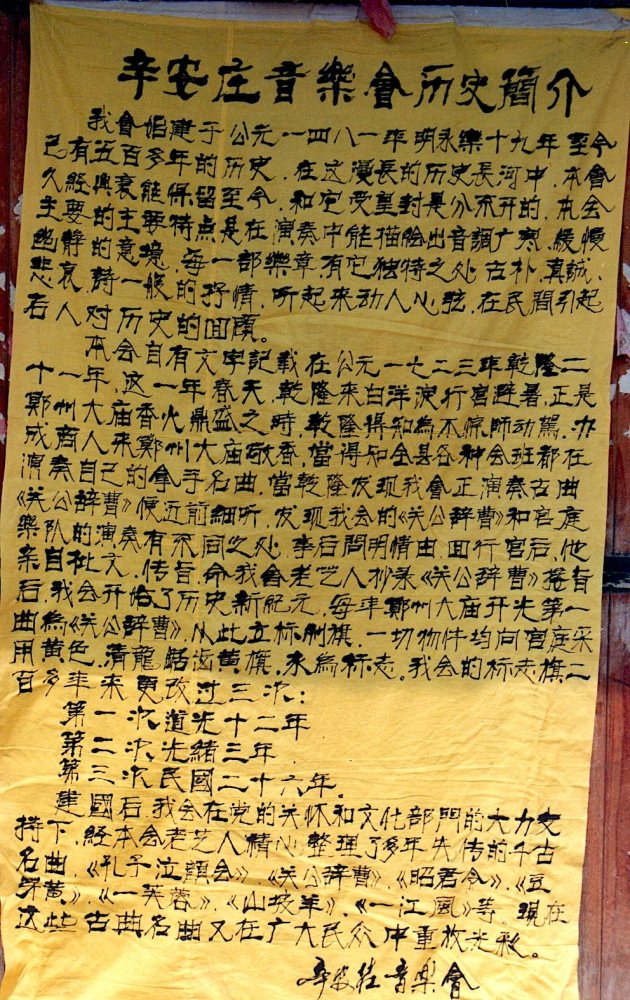

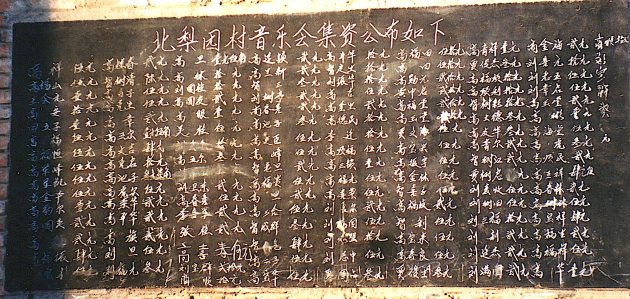

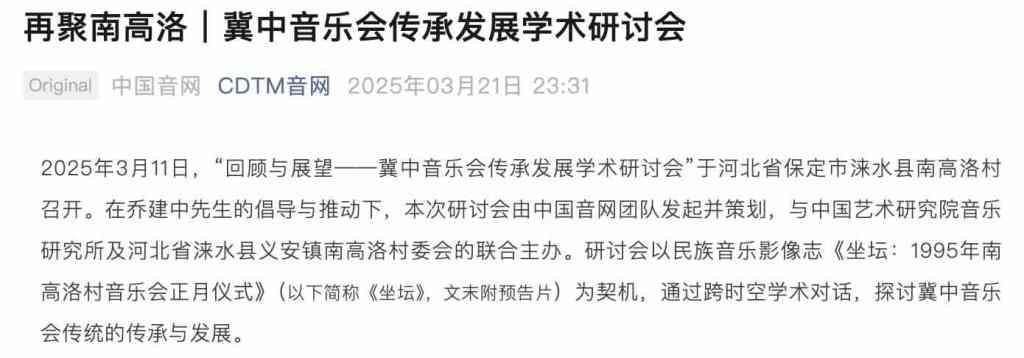

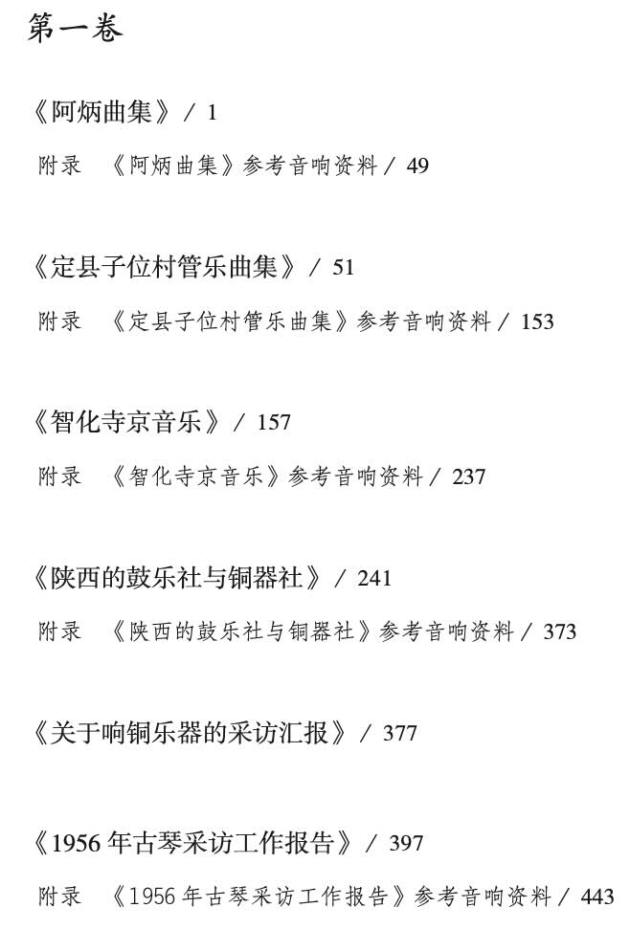

The Yuepu bian team, 2017.

The Yuepu bian team, 2017. Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,

Gongche score, West An’gezhuang village,

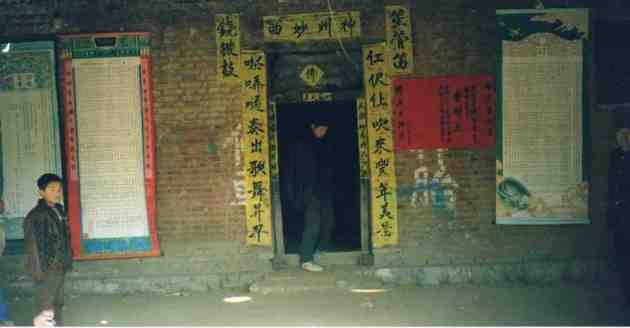

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

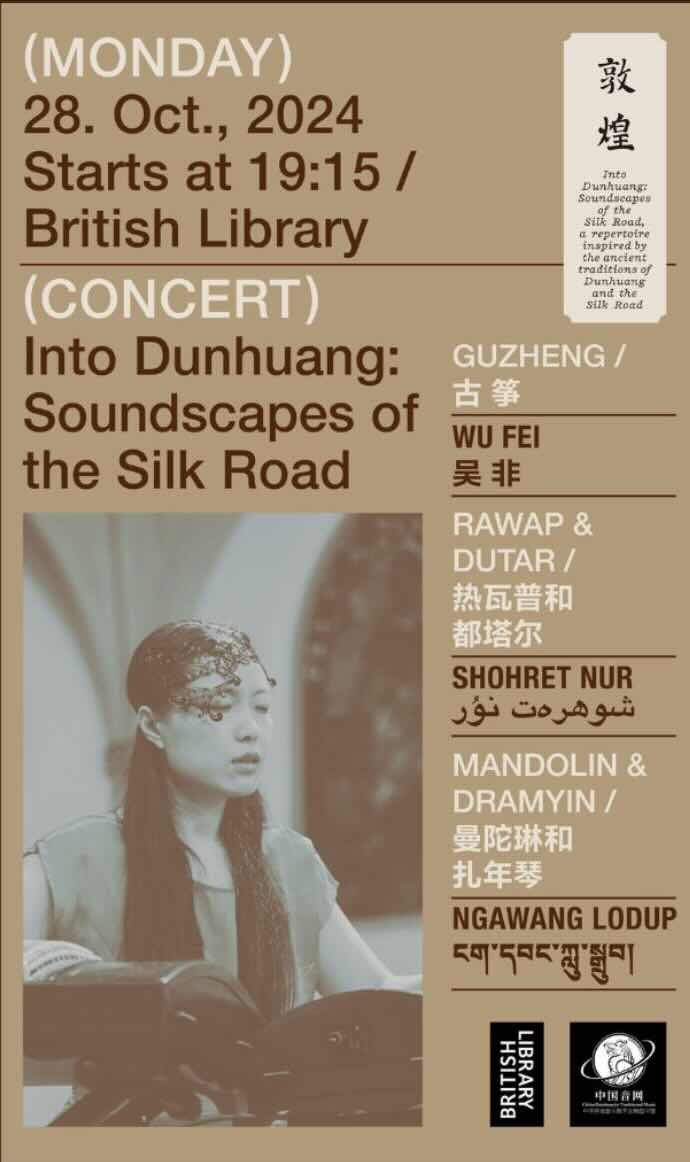

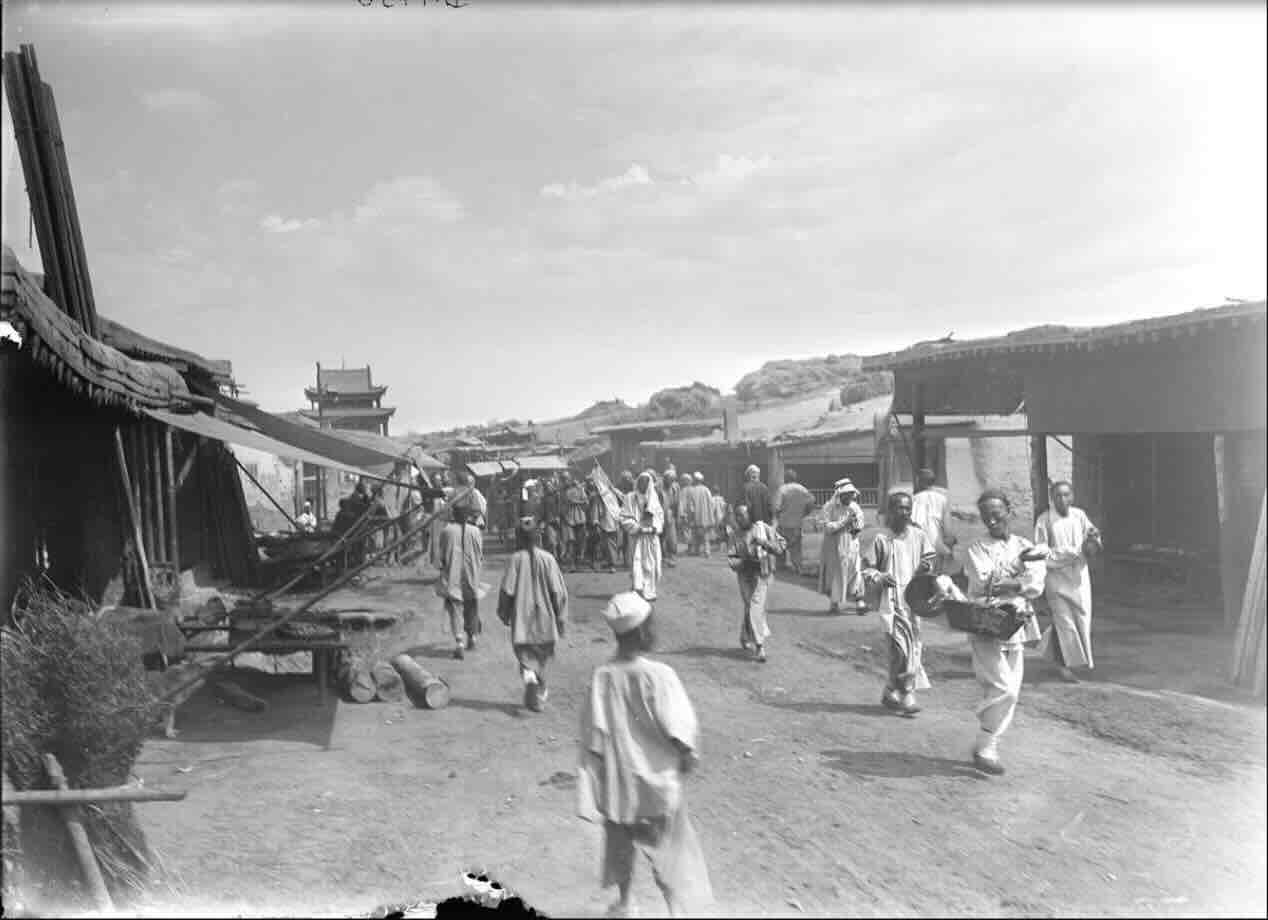

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century):

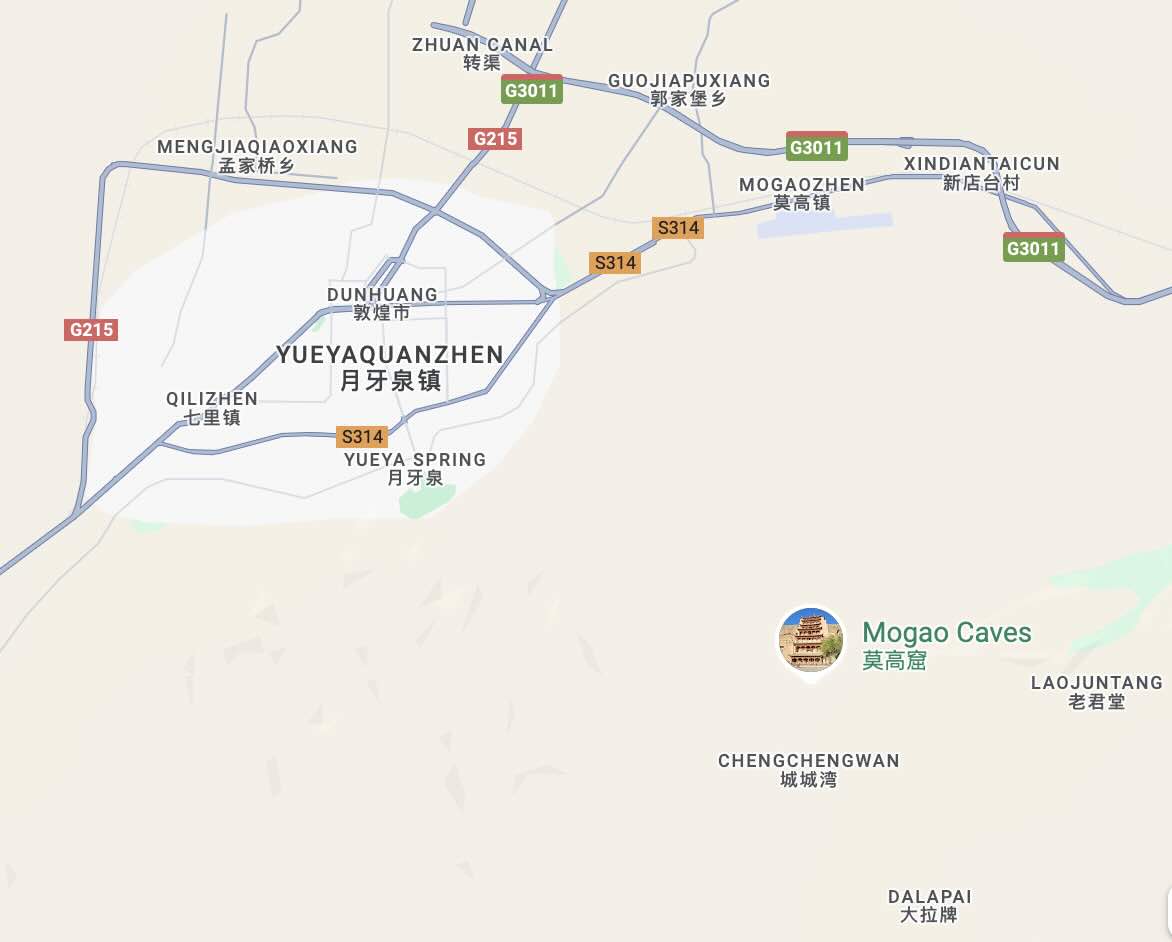

Photo from German Central Asian Expedition, undated (early 20th century): The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps.

The Dunhuang region today. Source: Google Maps. Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail).

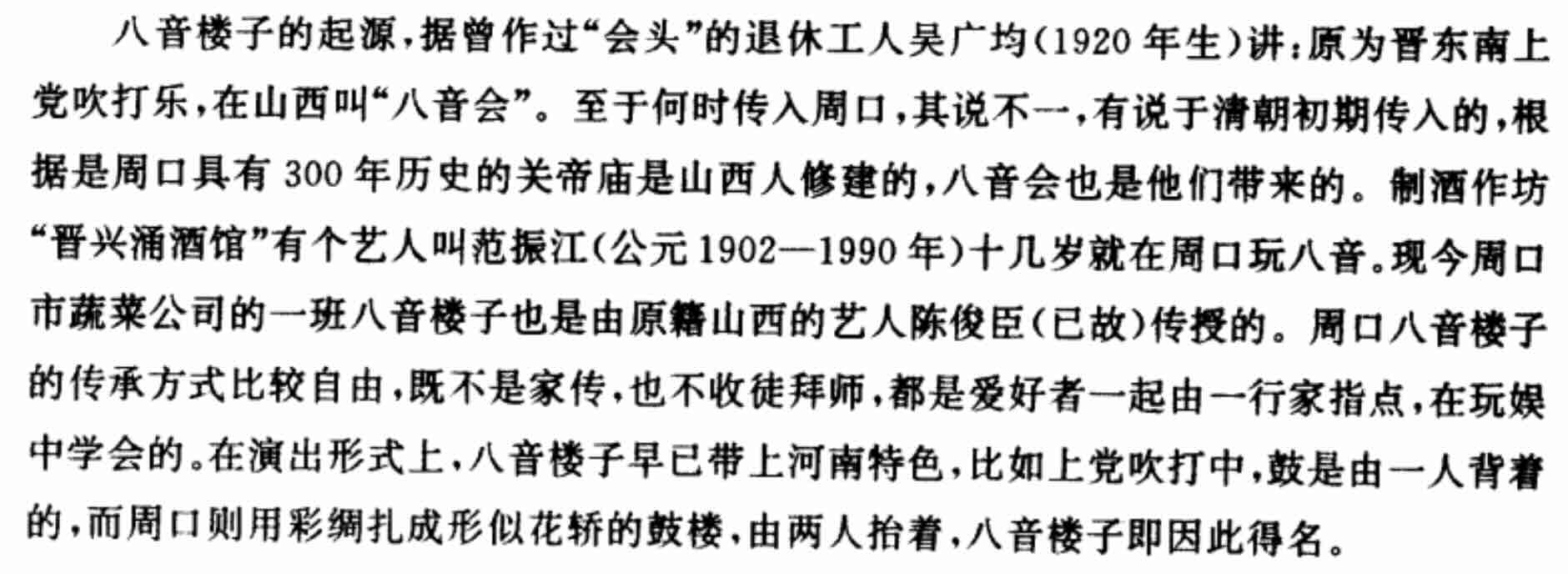

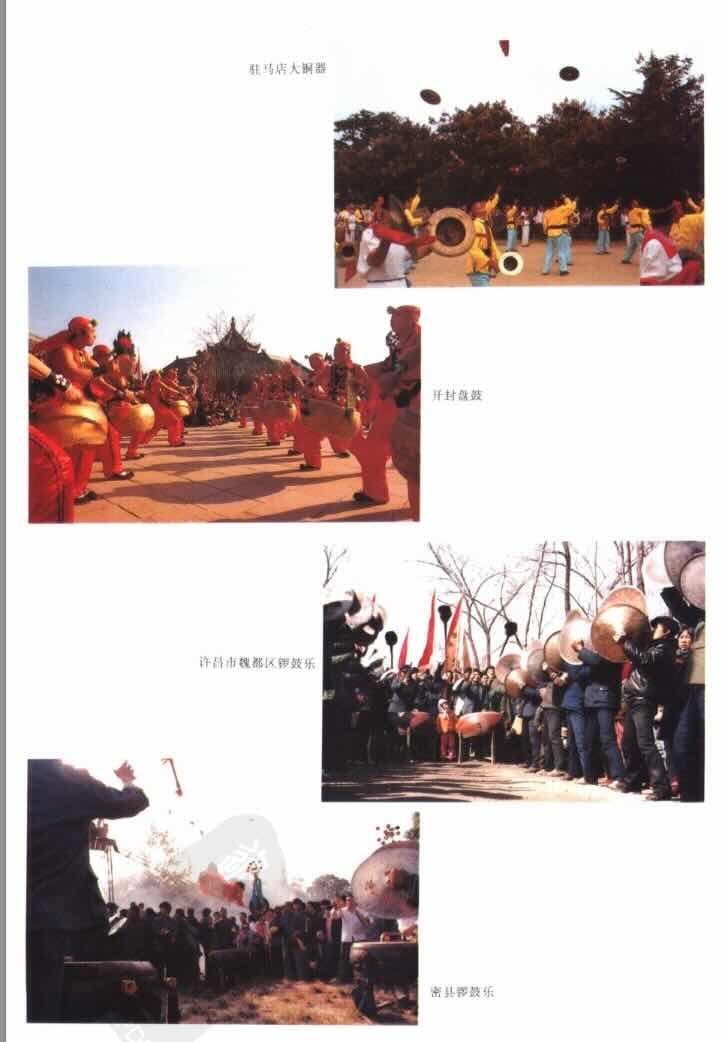

Konghou, Cave 285, 6th century (detail). Henan municipalities.

Henan municipalities.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

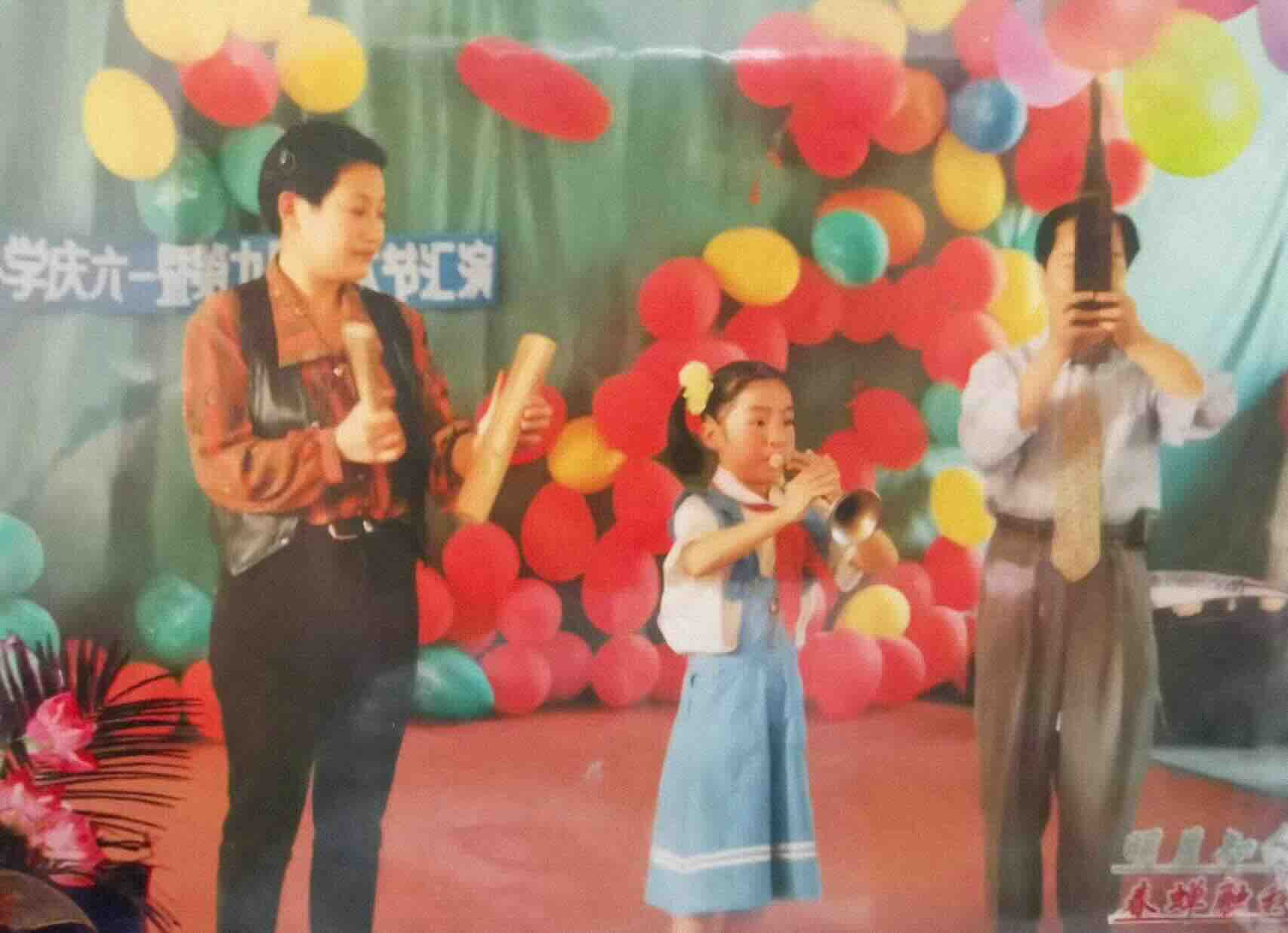

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents.

The Li family Daoists perform the

The Li family Daoists perform the  Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Wencheng in 2021. Cool trousers, eh. Source: Weibo.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Li Peisen’s cave-dwelling in Yang Pagoda village.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

Great Open-air Offering ritual, White Cloud Temple, Beijing 1993.

©BBC/Mark Allan. Source:

©BBC/Mark Allan. Source:

Benjamin Bruns, Christian Immler, Masaaki Suzuki.

Benjamin Bruns, Christian Immler, Masaaki Suzuki.

Ghost King,

Ghost King,  Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

Yankou at Xujiayuan temple fair, north Shanxi 2003.

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

The Zhaobeikou ritual association leads Releasing Lanterns ritual on Baiyangdian lake,

As to France, even I might hesitate to try out

As to France, even I might hesitate to try out

Not so much an impromptu pre-match party as

Not so much an impromptu pre-match party as

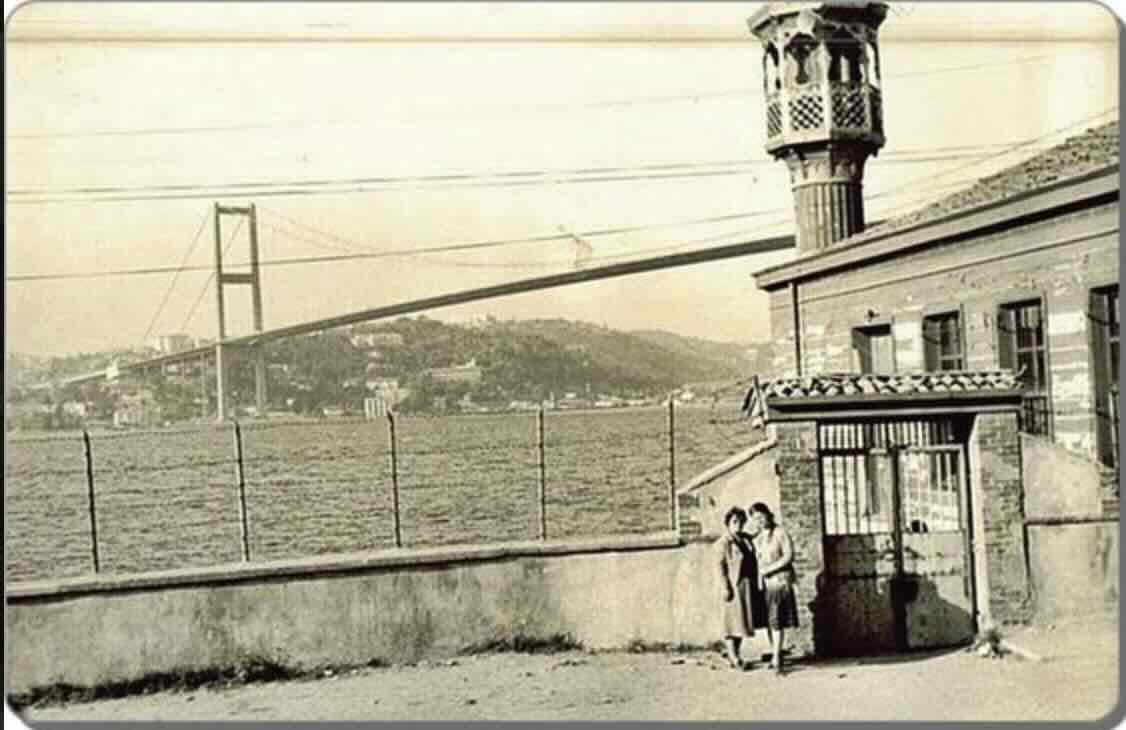

It’s taken me all this time to visit the bijou rectangular wooden mosque further up the coast towards the bridge—just below the mansion of Sultan Abdülhamid’s cultured confidant Cemil Molla (1864–1941), who sometimes served as imam there, and just past the yalı waterside residence of Sare Hanım (1914–2000), aunt of left-wing poet Nâzım Hikmet (see

It’s taken me all this time to visit the bijou rectangular wooden mosque further up the coast towards the bridge—just below the mansion of Sultan Abdülhamid’s cultured confidant Cemil Molla (1864–1941), who sometimes served as imam there, and just past the yalı waterside residence of Sare Hanım (1914–2000), aunt of left-wing poet Nâzım Hikmet (see

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

Nao and bo cymbals of the Tianxing dharma-drumming association,

Shifan band, 1930s.

Shifan band, 1930s. Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).

Jinmen baojia tu shuo (1846).