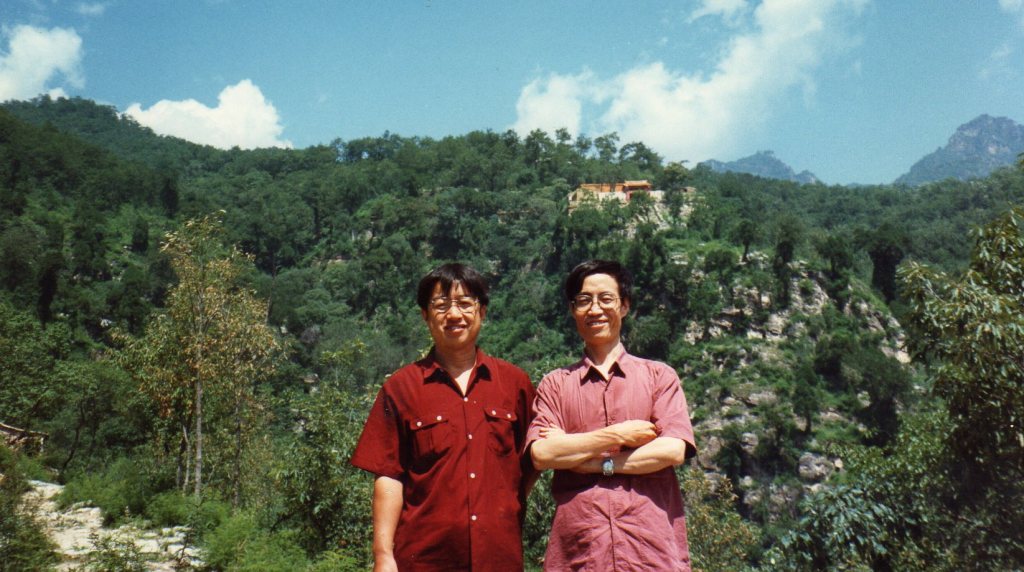

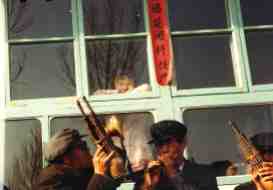

Shan Zhihe at home, 1998. In background, his older son Shan Ming.

My book Plucking the winds is a historical ethnography of Gaoluo village in Hebei just south of Beijing, focusing on its amateur ritual association. I’ve already posted several vignettes assembling material from the book (listed here); so here’s another one: the story of the venerable Shan Zhihe 单之和 (1919–2002).

By the time of our stay at Gaoluo in May 1996, while my fieldwork with Xue Yibing was going well, we still hoped to be able to visualize the earlier 20th century in greater detail. One evening, invited to supper with our urbane friends Shan Ming and Shan Ling, now among the leaders of the ritual association, we finally met their elderly father Shan Zhihe.

Like his own father, though never a practising member of the village ritual association, Shan Zhihe was a long-standing benefactor. Whereas most Gaoluo villagers had little or no experience of the world beyond a day’s walk, Shan Zhihe had travelled quite widely, and his father even further. Although he spent little time in Gaoluo between 1931 and 1951, some of our most personal information for the changing times under the Republican era, Japanese occupation, and Maoism derives from our sessions with him.

His own experiences through the complex events before and after the 1949 Liberation don’t fall comfortably into the pattern prescribed by official jargon. After his higher education was disrupted by the Japanese invasion in 1937, he found himself working “on the wrong side” in the 1940s. Though his family was then handicapped with the label of “rich peasant”, and he never held any official position in the village, he was a much-admired figure.

Shan Futian

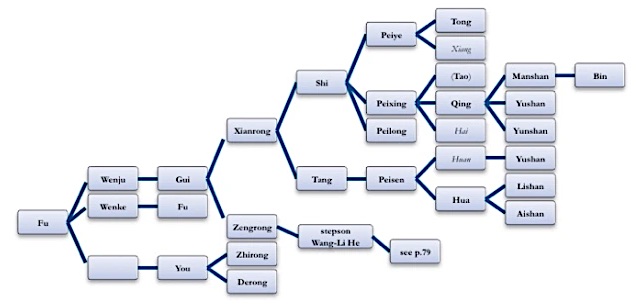

First Shan Zhihe narrated the remarkable story of his father Shan Futian, born into a very poor family in South Gaoluo in 1882. That very year his own father was beaten to death after being framed for the stealing of a donkey. The orphaned Shan Futian studied at the village private school for only three winters. He must have married not long after the 1900 Boxer uprising. His bride came from the Eastgate quarter of Dingxing town nearby. What with chaos of the Taiping uprising of the 1850s and the Boxers, villagers in the area, situated between the strategic centres of Beijing and Baoding, were constantly fearful for their unmarried daughters. So her family had sent her off to relatives in an isolated village just northwest of the Houshan mountains, centre of the cult to the goddess Houtu in whom locals still believe. As tradition demanded, the betrothed couple were not to meet until their wedding day. Shan Futian’s house, on the site of their present house, had only two bare rooms covered in thatch, empty apart from a clay vat to store millet.

But Shan Futian’s fortunes soon took a turn for the better. In about 1910 he found a job through relatives as tea-boy at an inn in Xiheyan in central Beijing, near the Forbidden City. There he earned the pittance of 12 dazir per month, equivalent to about 20 yuan today, according to Shan Zhihe; half of this he sent to his family back in Gaoluo. One day a general called Cai Chengxun came to the inn and noticed Shan Futian’s impressive build and honest demeanour. Cai was a platoon leader in the retinue of Yuan Shikai, who stepped in after the collapse of the Qing government and proclaimed himself emperor before his death in 1916.

Shan Futian now leapt at the invitation to become a bodyguard for Cai Chengxun: as a tea-boy he was bullied, and he couldn’t wait to move on. When Cai was promoted, he gave Shan Futian the post of banner-official in his cavalry. Shan was soon sent on duty to Baoding, where his oldest son Zhizhong was born in 1917, and then to relieve the garrison at Zhangjiakou further north, capital of Chahar; again, after some time his wife was able to join him there, and Shan Zhihe himself was born there in the 3rd moon of 1919.

Warlords were engaged in fierce fighting through the 1920s. The complexities of the political history of the time need not concern us here, but briefly, in 1922 Cai Chengxun, along with another warlord Sun Chuanfang, was sent by Cao Kun to reconquer the distant southern province of Jiangxi. Cai “bought” the governorship of the province, while Sun went on to control Fujian. Based at the Jiangxi capital Nanchang, Shan Futian now acted as cavalry commander.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

But without a patron Shan Futian found the work difficult, and in about 1927 he returned north, having made little money. After a brief reunion with his family in Gaoluo, he was introduced by a relative to do business back in Zhangjiakou. Before long he moved still further north to what is now Hohhot in Inner Mongolia, riding by camel. There he opened a leather business called Total Victory Leather Corporation; he also opened a public baths there in partnership with a relative from Dingxing. Different trades in Beijing were often monopolized by people from a particular area of the surrounding Hebei province; people from Dingxing and Laishui counties (the area of Gaoluo) used to work at public baths—this remained a traditional speciality of Gaoluo villagers right until the 1950s.

Shan Futian was one of several opium smokers in South Gaoluo, along with landlord Heng Demao and village bully He Jinhu. As Shan Zhihe observed, “It wasn’t just the rich who smoked: sick people and general reprobates also had recourse to it. I reckon no more than ten people in the village had the habit”. In 1935 Nationalist official Wang Zuozhou held a bonfire in the county-town as part of anti-opium campaigns throughout China. No-one heard of any such campaign reaching Gaoluo, but the habit—or perhaps rather the addicts themselves—must have died out soon after the Communist Liberation.

Early days of a scholar

Seated magisterially at his fine eight-immortals table, Shan Zhihe now began to relate his own story to us. Third of Shan Futian’s four children, he was born in 1919 at Zhangjiakou, where his father was then based. He and his older brother were given their “official names” Zhizhong and Zhihe after coming of age with the “lesser capping” ceremony. They were so named because their father’s public baths in Hohhot were called Zhonghe (Loyalty and Peace) baths; their names showed that the baths would one day belong to them.

Back in Gaoluo, the Juma river just east of the village had flooded in 1917. Though the flood was not serious and no-one died, it is still famous today in Gaoluo. The only other major flood in the village occurred in 1963. Gaoluo was fortunate, since throughout the whole area floods were frequent and devastating; indeed the village’s long-term immunity from natural disasters is still commonly attributed to the divine blessings brought by its ritual associations.

With his urban education, Shan Zhihe came to know the year of his birth, 1919, as the year of the May Fourth movement, a great urban intellectual ferment modernizing literature and social thinking. In fact, most villagers probably knew nothing of this movement: as amateur historian Shan Fuyi pointed out to us, the only big national historical event villagers definitely knew of was the Marco Polo Bridge incident on 7th July 1937, which unleashed the Japanese invasion. And if they do know such dates, they know them only in terms of the 8th or 26th years of the Republic, not by the official Western calendar.

Rather, most Gaoluo inhabitants know the 8th year of the Republic (1919) as the year of a serious epidemic in the village. In the heat of the 6th and 7th moons, “just as the melons were ripening”, villagers started to get stomach cramps and diarrhoea, death following quickly. Over sixty people died within a month. When one of the coffin-bearers died too, no-one dared observe proper funerals any more—the ritual associations too must have stayed away.

By now Shan Zhihe’s father was doing well in his business enterprises in Hohhot, and had bought up several dozen mu of land back in Gaoluo. In 1922, Shan Zhihe, still only 4, was sent back to South Gaoluo while his father went off to war in distant Jiangxi. Three years later he began attending private school in the village, studying along with forty or fifty other children. The school was at the home of his first teacher, Yan Zhan’ao. Seated before a portrait of Confucius hanging on the wall, the pupils learnt the standard Confucian curriculum, such as Surnames of the hundred families and Document of one thousand characters. Young Shan Zhihe studied there for five years. Since the older masters were less clear in their enunciation, pupils preferred younger teachers like Shan Hongru.

School tuition fees were 3 silver dollars per year. The teachers lived well; apart from tuition fees, pupils were also expected to present gifts three times a year: not only at New Year, but also on the Double Fifth (5th moon 5th) and Mid-Autumn (8th moon 15th) festivals—which have since lapsed in this area. The value of these gifts depended on family circumstances: better-off families might offer a pig or a sack of refined flour, but some poorer families were unable to give anything, and the teachers never blamed them.

The 1930s

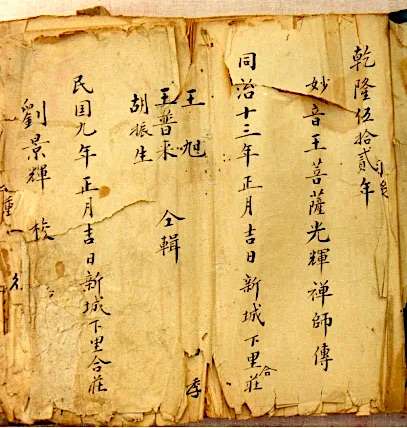

1930 donors’ list, South Gaoluo.

Shan Futian was among the five “managers” on the ritual association’s precious 1930 donors’ list.

My father always thought to give the most money to the association, as much as 5 silver dollars. That was a lot of money then—2 silver dollars bought a sack (44 jin) of refined flour in Beijing. Whenever donations were required, the leaders of the association would go round all the households in the village. Leading members of the Heng lineage always gave last, so that they could display their economic power by giving the most, a bit more even than my father, and “taking first place”.

More charitably, some said it was also so that they could make up for any shortfall in donations. Indeed, on the 1930 list Heng Jun and his son Deyong head the list, before Shan Futian.

On the 6th day of the 9th moon in 1931, just a month after the benediction of the Catholic church, our venerable mentor Shan Zhihe, now 13, left Gaoluo to join his father Shan Futian in distant Hohhot, where he joined in classes of the province’s 4th Primary Comprehensive. Shan Futian wanted his son to continue his education; as we have seen, his own father was a pauper beaten to death without the least pretext, and Shan Futian himself had been poor and uneducated; persistent Confucian values still allotted far higher prestige to the scholar than to merchants like him. Having had such a hard time, he now considered giving his children an education more valuable than any material inheritance he might leave them. I wonder how this decision seems now: many educated Chinese today feel effectively discriminated against for having an education, not only during the Cultural Revolution, but under the market reforms since.

Shan Zhihe recalled ritual life before the Japanese invasion. I cited his account of processions to pray for rain here. He also had insights on the Italian Catholic missionaries, led by Bishop Martina, and the building of the church in 1931.

On the 6th day of the 9th moon in 1931, just a month after the benediction of the Catholic church, our venerable mentor Shan Zhihe, now 13, left Gaoluo to join his father in distant Hohhot, where he joined in classes of the province’s 4th Primary Comprehensive. Shan Futian wanted his son to continue his education; as we have seen, his own father was a pauper beaten to death without the least pretext, and Shan Futian himself had been poor and uneducated; persistent Confucian values still allotted far higher prestige to the scholar than to merchants like him. Having had such a hard time, he now considered giving his children an education more valuable than any material inheritance he might leave them. I wonder how this decision seems now: many educated Chinese today feel effectively discriminated against for having an education—not only during the Cultural Revolution, but under the market reforms since.

Shan Zhihe takes a bride

The next time Shan Zhihe returned to Gaoluo was for his wedding in the spring of 1937. One fine morning during New Year 1998 he finally described it for us; he had omitted to mention it during our previous talks, for reasons which will soon become clear.

My Beijing companion Xue Yibing and I both relish his refined conversation. He too is always glad to see us, to chat with relatively educated outsiders about current affairs and history, reflecting on and trying to make sense of his own extraordinary life. With his father’s portrait overseeing us, we sit round his lovely table munching melon seeds in our overcoats (it’s still terribly cold), his children and grandchildren regularly refilling our teacups.

After graduating from primary school in Hohhot, young Shan Zhihe was sent to secondary school in the Xuanwu district of central Beijing. On the 26th day of the 2nd moon in 1937, aged 19, he took leave from his studies to make a special trip back to South Gaoluo for his wedding. The betrothed couple, naturally, had never met. His bride came from the Eastgate quarter of Dingxing town, just like his mother, whose family had arranged the match. She had bound feet and was uneducated; Shan Zhihe was full of modern thinking and had learnt to oppose “feudal customs”, but he had to obey his parents. His return to Gaoluo must have seemed like surrendering himself to the servitude from which his education was promising to free him.

This was to be one of the last lavish weddings in the “old society”, costing the astronomical sum of 300 silver dollars. His bride was carried in an expensive new sedan; Shan Zhihe himself rode a sedan borrowed from landlord Heng Demao. The procession to meet the bride at Dingxing, 5 km distant, started out in pitch darkness at 4am: to set off back home with the bride after midday was taboo, spelling ill-fortune for the match.

The amateur ritual associations perform only for the “white rituals” of funerals, not for the “red rituals” of weddings. For the latter it is common to hire a professional shawm-and-percussion band, known as “blowers-and-drummers”. Since Gaoluo itself had no such band, one was hired from Shiguzhuang village just north. On the procession to collect the bride, the shawm band played as they passed through each village, called “crossing the villages”, as firecrackers were released deafeningly. By tradition the route back to the groom’s home must be different: they passed through Xicheng village in the Northgate area of Dingxing to Nanhou, crossing the river again at Wucun. On arrival at Gaoluo there was a sumptuous feast. The five blowers-and-drummers were handsomely rewarded with half a silver dollar each.

Shan Zhihe spent a month in the village before returning to his studies in Beijing, leaving his new bride behind. Apart from taking part in the lineage observances for the Qingming festival, it was the time of the 3rd moon festival for the goddess Houtu, when many villagers went on pilgrimage to the Houshan mountains. It was also Easter, and Shan Zhihe recalls seeing Bishop Martina ministering to his flock in Gaoluo.

Even in a society in which gender equality was still not remotely on the agenda—we saw the dreadful isolation of Woman Zhang—Shan Zhihe and his wife were to make a particularly incongruous couple, as he recalled dispassionately for us in 1998. She was what he now calls a “housewife” (jiating funü, a term which reveals his own education), and hardly literate; she was five years older than him, and with her bound feet was barely mobile (that was the idea, of course); he was tall and commanding, a scholar with ample experience in the outside world. Couples simply weren’t seen in public. She used to nag him to take her to watch the local opera; one day he had to give in, but as he says they must have made quite a spectacle themselves, with him reluctantly trying to adjust his manly stride as she hobbled along trying to keep up. They never went out together again, and she never forgave him. As he recalled wistfully, they never exactly had any problems: “She didn’t curse me, and I didn’t beat her.” When she died, on the 13th of the 7th moon in 1983, the funeral was quite grand; the ritual association performed, and lavish paper artefacts were displayed and burned, though there was a continuous downpour.

Courteously accepting another cigarette, Shan Zhihe reflects: “My brother and I were both victims of the feudal system of marriage. You can’t blame my parents, they were products of the system themselves. My older brother married a couple of years before me, in 1935, but then went away to study in Baoding; in 1939 he got into the 29th Army, stationed in Hebei, and after going south with the army he stayed there. It was all just to get away from the wife! She stayed behind in Gaoluo the whole time—she was only able to remarry after they got a postal divorce in 1957.”

Incidentally, in 1998 there were still about forty or fifty women in the village with bound feet; of those above 70, only one had natural feet.

The devils invade

In the summer of 1937, back in Beijing after his wedding, Shan Zhihe was in the midst of his studies when the “7th July incident” (Qiqi shibian) occurred. This battle between Chinese and Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge, midway between Beijing and Gaoluo, marked the formal outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japan. It was a decisive moment in modern history for villagers, which they often call simply “the incident”. Of course, the preceding period too transpires to have been anything but rosy, but they often periodize cultural loss by this date, rather than by the Communist “Liberation” some ten years later—the Japanese invasion tacitly marking for them the increasing control of the Communists over their lives, as I eventually deduced.

With the whole Beijing area in chaos, Shan Zhihe eventually made his way back to Gaoluo on foot, by a long route avoiding the area of the Marco Polo Bridge, arriving back home late in July 1937. But what was he supposed to do now? His father had indeed blessed him with an education, and by now he didn’t relish the prospect of taking up as a peasant. The very fact of his education also made his situation precarious, for rival factions would seek to exploit his knowledge, and it would be difficult to choose his own path.

A month or so after his return to Gaoluo, it was clear that the Japanese advance along the main transport routes south could not be contained. Shan Zhihe’s older brother Zhizhong was part of the army which engaged the Japanese at Mentougou west of Beijing, but by the 7th moon they had to retire in defeat. Ordered to regroup at Zhengzhou, quite far south, they were constantly retreating through the area—Shan Zhihe’s mother was busy making bread for them. Zhizhong stopped off in Gaoluo for three days. After he resumed his journey, the brothers were not to meet again until after Liberation, over ten years later. Zhizhong later went off to work in Hubei province far to the south.

Their father Shan Futian was still in distant Hohhot. Shan Zhihe, though reluctant to abandon the family’s considerable property in Gaoluo, was responsible for his mother and sisters, and resolved to take them south out of danger. It was only when they heard the sound of heavy artillery that they decided they must go. But before they had even reached Baoding, they heard that the Japanese had already advanced as far as Shijiazhuang, still further south. Flight was impossible—they had no choice but to return to Gaoluo.

Japanese warplanes bombed Laishui county-town at 8am on 17th September (the 13th of the 8th moon) 1937, and that same day Japanese troops first entered Gaoluo. Coming from the direction of Wucun to the south, they were just passing through; they had about fifty tanks, and were covered by aircraft. The troops entered the village before Woman Zhang could take her children to the church to hide; they passed by her house. In order to dissuade them from murdering them all and setting fire to the village, the village leaders went out to welcome them. Before the Japanese even entered the village, they shot dead a villager who rashly stuck his neck out to look, but after entering Gaoluo they harmed no-one, just asking for fresh water, eggs, and meat. Shan Zhihe himself, along with Cai Ming (a sheng-player in the ritual association who worked as a pig-slaughterer), was responsible for looking after them and giving them water—the Japanese made them drink some first to be sure it wasn’t poisoned. Though they soon went on their way after a token search, Japanese cavalry and infantry passed through constantly for several days on their way to Baoding, and Gaoluo villagers had to look after them.

Seeing our evolving sketch-map of the village gave Shan Zhihe conflicting feelings:

Before the Japanese arrived they had prepared maps which they used when they first entered the village—they made me point out the way to Baoding. In the first party of Japanese troops were some savages [Ainu?] from Hokkaido. When they entered the village they caught some chickens and tore them to bits, eating them raw. When the troops discovered my hands weren’t calloused like those of a peasant they pointed their bayonets at me. I frantically tried to explain by gestures that I ran a baths, and they let me off.

The lawless conditions of the early 1930s had prompted many villagers to arm themselves. Soon after the Japanese invasion in 1937, some Gaoluo villagers sought to set up “Anti-Japanese brigades”. Villagers with guns were invited to join the new militia or at least to give their guns to the resistance effort. Within a couple of days some two hundred volunteers had assembled, including Catholics like Cai Chen and Cai Xing. The new militia called itself by the grandiose title of “The Rear Anti-Japanese self-protection troupe”, and even drew up a constitution. The house of North Gaoluo landlord Yan Shide served as command-post.

But educated Shan Zhihe soon found with dismay that most of the recruits were just village good-for-nothings. While a student in Beijing, he had taken part in patriotic demonstrations boycotting Japanese goods. Now finding himself back in his home village, taking his gun along and soon becoming one of the leaders of this motley crew, he was full of misgivings. Untrained, they were a menace to people outside their own village. “Ordinary people didn’t understand what this ‘anti-Japanese’ stuff was all about anyway, they thought the Japanese devils were just another bunch of bandits.”

The Japanese, learning that Gaoluo had organized a “Red Spears Association”, now sent a division of troops to “encircle and suppress” them. Shan Zhihe had a cousin called Wang Futong, whose family was quite well-off, owning over 100 mu of land. Wang was notorious as a wastrel who kept bad company. When an enemy of his spread a rumour that he was a militia leader, the Japanese came looking for him. Shan Zhihe had gone to Dingxing county-town that day to buy shoes for the militia, and by the time he got back the Japanese had gone, having failed to find Wang. But that was the end of the Gaoluo militia: some hid their guns or threw them down the wells, some went into hiding, while others joined militia groups in other villages, calling themselves anti-Japanese but actually plundering ordinary Chinese houses.

Cultured Shan Zhihe obviously had no future in such a militia. He handed in his gun and took no further part. Events now forced him to flee Gaoluo. Before long his profligate cousin Wang Futong was murdered by a drinking-buddy called Huo Zhongyi, leader of the militia in Xiazhuang just east of the river. Afraid that Shan Zhihe would seek revenge, Huo Zhongyi decided to “destroy root and branch”. He had Shan Zhihe summoned to the house of South Gaoluo landlord Heng Demao, but Shan suspected a trick and decided to flee. For a while he hid out at his grandmother’s house in the nearby town of Dingxing, and then set off to find his father again in distant Hohhot. The 10th moon of 1937 had still not arrived—an eventful start to his married life.

In occupied Hohhot

Shan Zhihe had already begun telling us his story in Gaoluo in 1996. We were back in Beijing for a few days between visits when we learned that he too had come there to stay with a family who needed his medical help. Back in the frenzy of ring-roads and fancy hotels, we missed Gaoluo already; glad of the opportunity to seek his guidance again, we asked him to continue his story for us.

Hohhot, 1930.

Source: https://www.xuehua.us/2018/07/23/罕见历史老照片,1930年蒙古人记忆中的呼和浩特!/

Shan Zhihe left for Hohhot in the 9th moon of 1937, where his father was still running a public baths. Shan Zhihe’s wife, as well as his mother, were able to join them in 1938; the sons Shan Ming and Shan Ling were born there in 1942 and 1948 (for naming customs, see here). But the war had made business enterprises highly subject to intimidation, as Shan Zhihe soon found out when he started working at the baths. Early in 1938 posters advertising for examinations for the police force seemed to offer him a better alternative. Shan Zhihe was a tall and well-educated young man; he passed the exam with no trouble. Only when he started the Japanese-style military training did he realize that what the poster had presented as a force for the protection of Hohhot was in fact a training for the collaborative “traitor army”. By the time he realized he had been conned, it was already too late, and Shan Zhihe was now subordinate to a Japanese police chief. If his story may sound disingenuous, it apparently didn’t seem so to later Communist investigators.

Shan Zhihe was first sent to work at the police station in Great South Street, the most affluent quarter of Hohhot; then after a month he was promoted to personnel management in the police department in the old town. Over the following years he gained promotion through the ranks of the Mongolian and Japanese armies. “I had contact with the Japanese all the time—I got to read the Japanese news, so I knew quite a bit about World War Two.” He was better informed than I about Dunkerque, which in itself was no great feat. He managed to save several Communist guerrillas: when the Japanese caught someone, friends got him to go and set things right, so they were set free.

In the 9th moon of 1942 Shan Zhihe at last got permission to return to Gaoluo for a visit. His military permit entitled him to carry firearms, and his first thought was to seek out Huo Zhongyi and “settle the debt” for the murder of his cousin. But he soon learnt that fate had done the job for him. Huo had gone over to the Japanese, and then, resentful of their cruelty, had resolved to rebel against them; but they had found out and executed him. Shan Zhihe spent only one night at home before setting off back towards Hohhot. On the way he spent a few days at the home of his older sister’s husband in Beijing, and applied for permanent leave from the Japanese army. This was granted, but after he returned to Hohhot he spent most of the next three years virtually unemployed, earning a bit from renting out rooms.

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Nationalist commander Fu Zuoyi had entered Hohhot and gradually “suppressed” the most evil of the Japanese collaborators. “Times were tough in Hohhot after the Japanese surrender”, recalled Shan Zhihe. “There was no coal, and no barley—we had to eat ‘secondary barley’, a mix of husked sorghum and husked barley. The Nationalists had heard that I was educated and had military training, and they offered me an official post in their army, but I refused. Still, I was only 26, in the prime of life. Frustrated, I could see no options for myself, and in 1946 I ended up as a medical orderly in a hospital at Hohhot. The hospital was of regimental rank, and orderlies were between 1st and 2nd lieutenants in rank.”

Under Maoism

Shan Zhihe worked as an orderly for the Nationalists in Hohhot through the civil war, witnessing different traumas from those taking place in Gaoluo. In 1948 he took some relatives to Beijing; a photo of him in military uniform shows his impressive stature.

Hohhot was “peacefully liberated” for the second time on 19th September 1949. For the time being the Shan family stayed on there; the family’s bath-house then had five rooms, two of which they rented out for use as a general store, selling off some of their furniture.

But eventually, as private enterprise under the Communists became untenable, the whole family had to return to Gaoluo. Shan Zhihe came back in 1951 with his wife, his daughter, and younger son Shan Ling—the first-born Shan Ming stayed behind with his grandparents, but he too came back with his grandmother in the 3rd moon of 1952.

The aged Shan Futian was last to return, in the following winter. By this time he was seriously ill. Ever filial, Shan Zhihe wanted to sell off the family’s property to help him buy medicine. The family had owned over 90 mu of good land before Liberation. Since they were absentee landlords, they had let villagers cultivate it; the villagers were liable to pay grain tax on it. But the Shans took only a nominal rent, and so upon land reform they were classified as “rich peasant” but were not made an “object of struggle”; they were allowed to keep over 40 mu of land, while the rest was parcelled out, but their property was not touched. Still, the family had been away from the village for the whole preceding period, and Shan Zhihe felt unhappy about his class label. Though the “hat” of landlord or rich peasant was not always brought into play (“neither hot nor cold”), it was a sword of Damocles.

As his father’s health declined, Shan Zhihe sold off 10 mu of the family’s remaining land in the hope of saving him, but Shan Futian wouldn’t let them dispose of more of their assets, and in the 6th moon of 1953 he died. Even in absentia he had been a longstanding benefactor of the ritual association, and his family used to give the association a banquet at New Year. Naturally the association played and performed the vocal liturgy for his funeral; Shan Laole played the drum, Chen Jianhe the guanzi. But the funeral was not especially grand, as Shan Futian had spent little time in the village. Since his son Shan Zhihe had done well since returning to the village by helping at the new village school, the teachers made a traditional offering of cloth.

Mindful of his dubious employment record serving Japanese and Nationalists, Shan Zhihe wrote a “self-examination” after returning to South Gaoluo in 1951. Investigators went to interview people in many places where he had been, but no “historical problems” were unearthed; everyone was full of praise for him. So, remarkably, he remained safe from assault—even through the Cultural Revolution.

Whatever his background, people like Shan Zhihe, the most educated man in the village with enviable modern learning, were much needed to consolidate the revolution in the countryside. He must have known he was skating on thin ice, and having to prove himself he now showed willing.

When I came back to Gaoluo they asked me to teach at the village school. I declined, but I did teach at the People’s School (the evening school) in the Sweep Away Illiteracy campaign of 1953. I was a leader of the West Yi’an district Sweep Away Illiteracy campaign then too. But I felt ashamed of my past, and threw myself into studying Marxism-Leninism, reading works like Das Kapital, On practice, and On contradictions. I read other revolutionary literature like How to make steel [an influential translation of a Soviet novel]. I taught the pupils about Marxism-Leninism, and won an award as a model teacher in the People’s School.

Opera

Apart from the four ritual associations of North and South Gaoluo—which managed to maintain activity through the first fifteen years after Liberation—both villages had an opera troupe, performing a local genre called bengbengr or laozi. In South Gaoluo in the early 1930s Shan Zhihe remembers his older brother Zhizhong getting money from his family to buy the troupe some costumes. But it had to disband after the Japanese invasion.

After Liberation the revamped South Gaoluo opera troupe acquired a great reputation locally. The troupe was to become a flagship for new official cultural policy, based at the village primary school. The reorganization of the troupe was strongly supported by the new Party Secretary Heng Futian, who thought it would be a good way of expanding the village’s influence.

The troupe now resolved to rehearse modern operas which had been created and performed in the revolutionary base of Yan’an in the 1940s: The White-haired girl (1945), as well as Liu Hulan (1948) and Wang Xiuluan. By performing these operas they identified directly with central official artistic policy on the modernization of traditional culture as canonized in Mao’s 1942 Talks at the Yan’an forum on literature and the arts—in stark contrast with the total impasse with the new political ideology which the ritual association continued to represent. Women now took part in the troupe for the first time.

Another main driving force for the opera troupe was Shan Zhihe. Though without formal dramatic training, he had gained experience of the arts while a student, and, despite his dubious work experience before Liberation, was respected as the most “cultured” person in the village. He now acted as director for The White-haired girl. He even brought out his father’s old clothes, hat, and pocket-watch to use as props for the part of the evil landlord Huang Shiren—a fine irony, since his own family had just been landed with the “hat” of rich peasant.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu.

Incidentally, as a sign of the times, when the Cultural Revolution ballet version of The White-haired Girl was revived in Beijing in 1996, some younger members of the audience missed the point spectacularly. The evil landlord is portrayed in the drama as shameless in his demands for repayment of debts from poor downtrodden peasants, and beats the heroine Xi’er’s father to death when he is unable to repay. At some early performances in the 1940s audience members had so hated the landlord that they virtually murdered the actor, and the plot had to be changed to reflect audiences’ hatred for him: in the revised version he is indeed sentenced to death rather than merely re-educated. But by 1996 his character attracted some sympathy: when interviewed, some said it was quite proper for the landlord to demand repayment! Official commentators understandably lamented the decline of morality: “Thanks to the introduction of a market economy, young Chinese are becoming business-oriented, and their comment reflects the philosophy of business.” Decades of socialist education had come to nought.

Like many Chinese, Shan Zhihe considered the social breakdown to have occurred only with the Cultural Revolution and the loss of integrity thereafter. As he reminded us, in the 1950s life was at last stable, and the Party was popular. Chairman Mao was revered: people said there had never been such a great figure in the whole of China’s long imperial history. The army served the people, fetching water and clearing the land for the villagers. Cadres abided by the “three main rules of discipline and the eight points for attention”, theme of a catchy new song. New Party Secretary Heng Futian was rushed off his feet for a whole month organizing the collection of grain taxes, and the village cadres just had a quick bowl of noodles before their meetings—there was not the least suggestion that they might be fleecing the people.

Shan Zhihe may have had reasons to thank the Party, but he voiced the feelings of many poorer villagers. People we met articulated no negative memories of the campaigns of the early 1950s, and I do not believe this was mere prudence. No-one found labour gangs at all sinister. Many of those who suffered, like the old bullies, were thought to deserve it. It was simply not in people’s vocabulary to sympathize with the plight of the Catholics. And as the landlords disappeared, people neither remembered them badly nor spared the sentiment to miss them. The political mood dictated from above was pervasive: people had no choice but to take part in the elaborate game of “snapping at each other”. People related to or erstwhile friends of those now classed as “elements” went through the motions. Sons of so-called rich peasants, such as young musician Shan Bingyuan, naturally had a tougher time than others from unassailable poor-peasant backgrounds. But even a cadre like Cai Fuxiang, with his impeccable revolutionary credentials, was traumatized by the violence of revolution.

As a former medical orderly, Shan Zhihe had later studied medicine under his older sister’s husband, and was now quite well qualified. He now started to treat patients for free in Gaoluo.

Despite their later nostalgia, many villagers must have been increasingly anxious as collectivization looked imminent. Some households certainly stood to gain from an efficiently-run system. By now the “rich peasant” family of venerable Shan Zhihe was poor: their labour force was weak and they had no experience of tilling the land, so they had no objections to joining the collective. Such families went along with the changes, but many already working efficiently with their own carts, tools, and draft animals saw communal agriculture as inefficient and alienating, and were reluctant to join. Though disgruntled, few were rash enough to articulate such thoughts: complaint was dangerous, and could instantly be interpreted as opposition to the sacrosanct state. The government had also just devised an unenviable class category of “new rich peasant”. Still, collectivization did arouse resistance and sabotage, and in many places (if not in Gaoluo) religious sects resurfaced to oppose it.

After the Great Leap Backward and the ensuing famine, a lull between extremist campaigns allowed a brief revival of the ritual association in the early 1960s. Among thirty new recruits in 1962 was Shan Zhihe’s son Shan Ling.

The Cultural Revolution, opera, and the reform era

Soon after the Four Cleanups campaign opened in 1964, Shan Zhihe wrote a letter to the authorities complaining of the unfairness of his “rich peasant” hat, but once the Cultural Revolution started he was unable to pursue it any further. He realized chaos would be unleashed as soon as he heard the ominous slogan “attack with culture, protect with force”, providing a pretext for violence. In Plucking the winds I describe the factional fighting that spread from the county-town to Gaoluo in 1966—including the remarkable rescue of the Houtu precious scroll. But despite his dubious past, Shan Zhihe remained immune from attack.

The village opera troupe had performed modern opera in the early 1950s, abandoning it in 1958 for the traditional bangzi style. By 1964, at the instigation of the county Bureau of Culture, themselves under orders as part of a huge national drive against the traditional “feudal superstitious” operas which had resurfaced widely, they started performing modern operas again. They then inevitably blew with the winds to serve as a Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team, performing the “revolutionary” model operas, as throughout China. By winter 1967 the troupe was performing revolutionary dramas like Shajiabang, Taking Tiger Mountain by strategy, as well as Stealing the seal (Duoyin 夺印, an opera about class struggle) and The commune-chief’s daughter (Shezhang de nü’er 社长的女儿). For most of our friends, erstwhile members of the utterly conservative, but now dormant, ritual association, the development of the opera troupe had an inevitability about it. Even ritual stalwart He Qing now relished playing the smugly virtuous revolutionary Li Yuhe in The tale of the red lantern.

But some other members were none too impressed. Shan Qing, then in his 20s, had learnt the bangzi style in 1962, and only wanted to perform the old operas; he didn’t approve of the model operas, so he withdrew. And despite having subscribed readily to the social goals of the 1950s, Shan Zhihe decided the Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team wasn’t his cup of Chinese tea.

But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the Boxer uprising (also the object of much fieldwork under Maoism), this was always a popular theme rallying the people against the evil foreign imperialists; following a 1959 film, by 1997 the story was taken up in a big way in a blockbuster film by veteran director Xie Jin, making propaganda for the handover of Hong Kong back to the Chinese. The county Bureau of Culture supported Shan Zhihe in his project, but it never came to fruition—too bad, as I joked with him, or I might have landed a part in the revival, though I’m not sure I’d be up to playing Queen Victoria.

But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the Boxer uprising (also the object of much fieldwork under Maoism), this was always a popular theme rallying the people against the evil foreign imperialists; following a 1959 film, by 1997 the story was taken up in a big way in a blockbuster film by veteran director Xie Jin, making propaganda for the handover of Hong Kong back to the Chinese. The county Bureau of Culture supported Shan Zhihe in his project, but it never came to fruition—too bad, as I joked with him, or I might have landed a part in the revival, though I’m not sure I’d be up to playing Queen Victoria.

For better and for worse, the economic liberalizations after 1978 effectively brought an end to over twenty years of Maoist policies. A new era now began. Class labels were finally abolished, as Shan Zhihe (who had suffered less than many for his bad label) reminded us, causing people to praise the national leader Deng Xiaoping as “Blue Sky Deng”.

In 1980, just as the commune system was being dismantled and the ritual association reviving, South Gaoluo villagers dipped their toes in the newly flowing waters of emergent capitalism as a group of enterprising friends tried organizing an “incense factory”, and soon (sorry, I can’t resist this) got their fingers burnt. The village brigade, led by Cai Yurun, back from the army and just appointed Party Secretary, as well as a keen new recruit to the reviving ritual association, took the lead. The incense factory was also an early experiment in business practices for Heng Yiyou, former “backstage” supporter of the United faction, soon to become a leading local entrepreneur. Even the otherwise sage Shan Zhihe, already in his 60s, took part. Also in 1980 he passed an exam at county level, promoted by the commune, and went on to open a private clinic in Dingxing in partnership with some colleagues.

In 1998 we paid him further delightful visits. Still supporting the association in his old age, by the standards of rural China in the 1990s he was comfortable, well looked after by his family.

Meanwhile a miraculous revival of the village opera troupe was under way. Political freedoms after the dismantling of Maoism then allowed them to restore the traditional style from 1979 to 1981, but economic pressures soon forced them to disband. They started rehearsing again in 1997. The newly formed group was an extension of the village’s new shawm band; thus several members of the ritual association were also taking part, including Shan Zhihe’s urbane sons Shan Ming and Shan Ling. The troupe’s repertoire now subsumed both traditional and modern styles. For New Year 1998 they were preparing classical bangzi excerpts as well as parts of their newer repertory such as Liu Qiaor and the teahouse scene from the Cultural Revolution “model opera” Shajiabang, still in bangzi style. But the revival exacerbated animosities within the ritual association.

Shajiabang, New Year 1998: Cai Tingwen as Nationalist general, Shan Rongqing on fiddle.

In contrast to the rather insular world of many peasants, the Shan family continued to be rather well acquainted with world events. Indeed, some other villagers too were interested in the Iraq crisis which was reported on Chinese TV—they questioned me about Britain’s role. But the Shan family’s curiosity was rather exceptional, going back to the early 20th century with Shan Futian’s experiences in Beijing, Hohhot, and south China, and continuing with Shan Zhihe’s own background of studying in Beijing and working for the Japanese and Nationalists in Hohhot.

Shan Zhihe, who over half a century earlier had learned of the Normandy invasion, had maintained his interest in world events: he mentioned the death of Princess Diana and the channel tunnel between England and France. So the whole family, including his urbane sons Shan Ming and Shan Ling, naturally had an interest in new culture from outside. They had good contacts in Beijing, where Shan Zhihe paid occasional visits; his daughter’s husband had retired early and become a taxi-driver, making a regular trip to and from Gaoluo—another link to the modern world of the Shan household.

* * *

For me, Shan Zhihe’s story encapsulates the complex transition from the old to the new society. I shared the villagers’ great respect for him. Of course he presented himself in a good light; nearly half a century after having to write “confessions”, Shan Zhihe doubtless found our visits a further opportunity to reflect on his experiences. Now he was writing his memoirs, only partly under the stimulus of our visits. As he reflected to me,

I’ve got a good memory, but my fate is no good. Otherwise after studying in Beijing I might have gone off to England to continue my education! The year the Japanese surrendered I was already 26, but by then it was too late. While I was working for the Japanese I managed to save several Communist guerrillas. But for having served the Japanese I was condemned to live and die in the village, a dismal life.

But things could have been far worse: he could so easily have been branded for life as a Japanese and Nationalist collaborator. By his own analysis, he had gone down the wrong road just once in his life. Having demonstrated against Japanese goods while still a student, he still couldn’t understand how he ended up as a policeman under their rule. Although he had done no wrong, it somehow seemed right that he should return home to reflect on his past and his future—not that he had much choice.

If many people with similar experiences were persecuted under the Communists, many also must have been well treated. It seems that the new leaders knew whom they needed, and that local loyalties also counted. But of course there were also innumerable senseless casualties in the Chinese Revolution; over the following years many Party members who suffered to help build the new society, and remained wholeheartedly loyal to it, were to be ruined. Shan Zhihe now had reason to be grateful to the Party. Psychologically his story is complex. He seemed sincere in parroting the Party-speak cliché of “I reformed my thought through labour and sweat”: layers of irony are hard to fathom.

But he had survived. “My father taught me two things: ‘If you make money, you mustn’t look down on people; if you become an official you mustn’t con people’—I’ve managed to live right down to today by those two mottos.” I believe him, too; his refined demeanour is a far cry from that of so many cadres and nouveaux riches under the reforms. By the 1990s, his family were living rather well; his children and grandchildren were bright. The family has survived—what more could they ask? Zhang Yimou’s moving film To Live (Huozhe, surely better translated as “Surviving”) gives an impression of this instinct. And many ordinary Chinese today still revere Mao, despite all the appalling gratuitous sufferings he inflicted on them, and are actually nostalgic for Maoism, admiring strong leaders; they are confused and alienated by the reforms since the 1980s. We must beware reading such alienation into the vicissitudes of the 1950s.

Do read Plucking the winds!

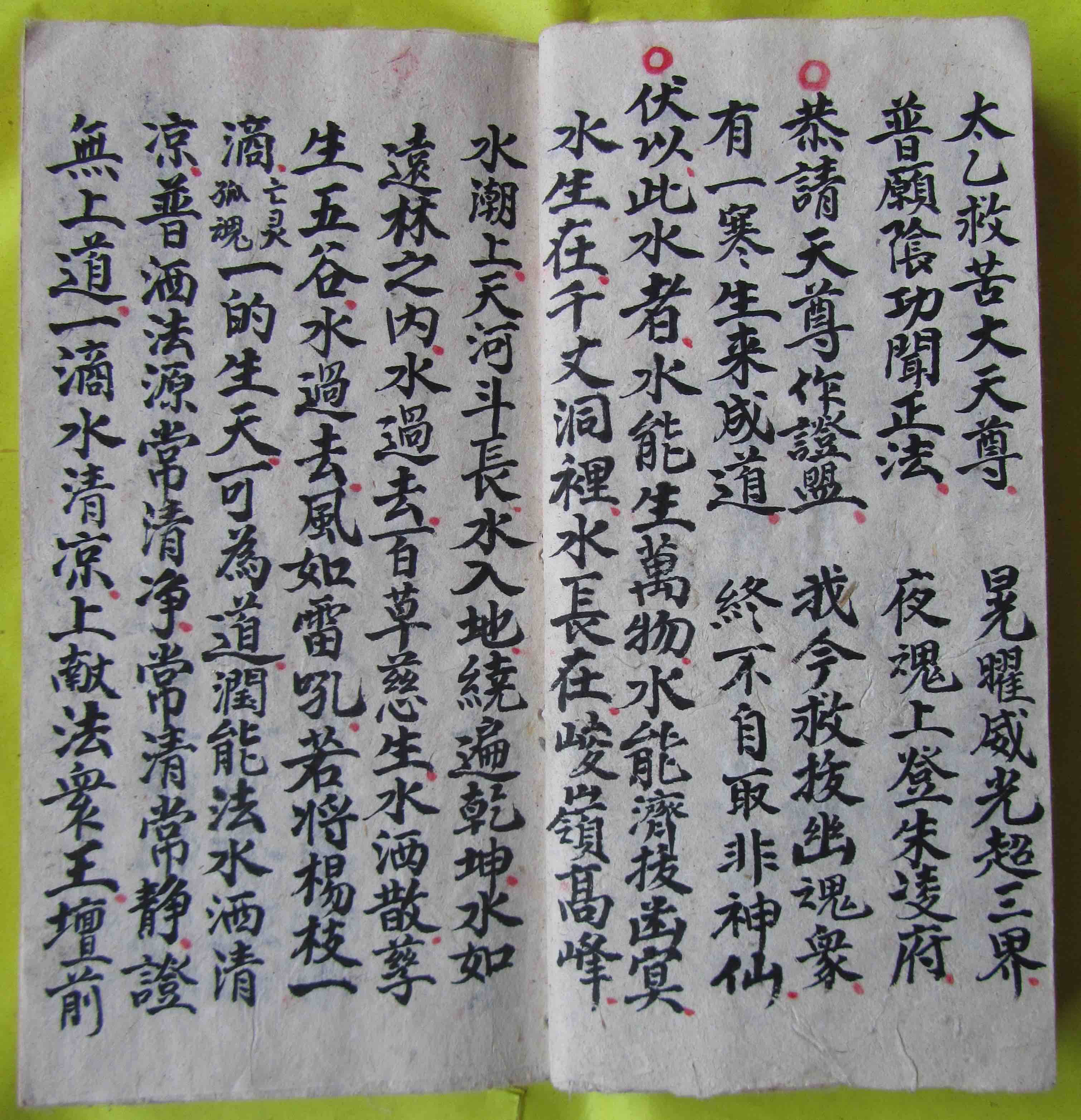

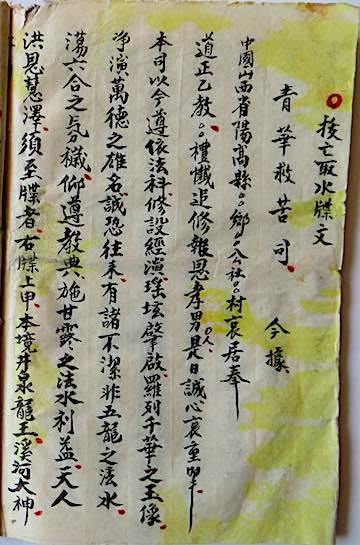

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual:

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual: The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

So I’m grateful to the exhibition for stimulating me to revisit some of my own material from the field. In this I’m always in awe of the incomparable erudition of

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions.

This reflects another common difficulty: we often seek to document history through major, exceptional events, whereas for peasants customary life is more routine. And apart from artefacts, much of the history of this (or any) period lies in oral tradition—which doesn’t lend itself so well to exhibitions. From

From

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

From Qing-dynasty Tianjin Tianhou gong xinghui tu 天津天后宫行會圖.

Mural (detail),

Mural (detail),

By this time

By this time

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

Cai Chengxun, victorious in battle, had now made his fortune. Returning north, he retired to his old home in Tianjin. “When the tree falls, the monkeys scatter”; Cai Chengxun’s retinue had now lost their patron. But Cai recognized Shan Futian’s honesty—Shan had never exploited his position in order to enrich himself—and before retiring he wanted to make Shan Futian mayor of De’an county, between Nanchang and Jiujiang, hoping Shan could use the opportunity to make a fortune for himself at last. Shan declined, afraid that his “lack of culture” would make the job difficult for him, although Cai offered him an adjutant. Instead he took the post of county police chief. The 1924 ceramic portrait of Shan Futian, which now had the place of honour overlooking the Shan family’s eight-immortals table, was fired at the famous kiln of Jingdezhen while he was serving in Jiangxi.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu.

The virtuous part of the heroine Xi’er’s father Yang Bailao was originally given to He Junyan, Party Secretary of the village Youth League. But he wasn’t up to it, and took the part of Huang Shiren instead, while Shan Zhihe himself took over the role of Yang Bailao—a quaint reversal of their allotted roles in the village. Secretary Heng Futian’s son, Deputy Secretary Heng Qi, took the part of the kindly servant Zhang Dashen. I wonder if the White-haired girl herself, mistaken for a spirit until it transpires that she is merely a common villager whose suffering had turned her hair white, would have reminded locals of their own goddess Houtu. But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the

But meanwhile he collected material in order to compose a libretto on the theme of Lin Zexu, hero of the Opium Wars. Like the