- Barbara Demick, Eat the Buddha: life, death, and resistance in a Tibetan town (2020).

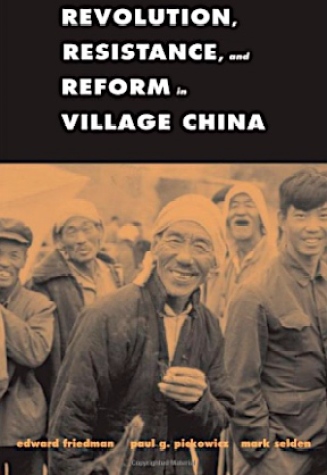

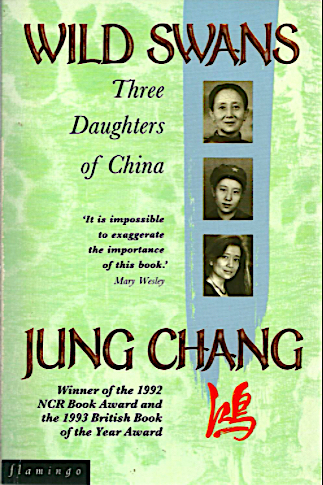

While academic studies of modern Tibetan history and culture have blossomed since the 1980s (see roundup here), the dense language of scholarly publications is often compounded by their prohibitive prices. So there is ample room for an accessible, affordable volume like this to reach a wider audience beyond academia. *

Demick researched her book Nothing to envy: real lives in North Korea (2010) while she was serving as Bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times in Seoul. Based on seven years of conversations, mostly with defectors to the south, as well as nine trips to North Korea from 2001 to 2008 and secretly-filmed video footage, the book is a rare window onto a closed society whose traumas and secrets remain hard to reveal.

By 2007 Demick was covering the PRC, where journalists also face ever greater challenges. From her base in Beijing, she began investigating the lives of Tibetans in the Ngaba region of north Sichuan, which was to become “the undisputed world capital of self-immolation”.

Besides the “Tibetan Autonomous Region” (TAR), the majority of Tibetan people within the PRC live in the extensive regions of Amdo and Kham to the north and east (comprising large areas of Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces), on which much recent scholarship has focused (see Recent posts on Tibet).

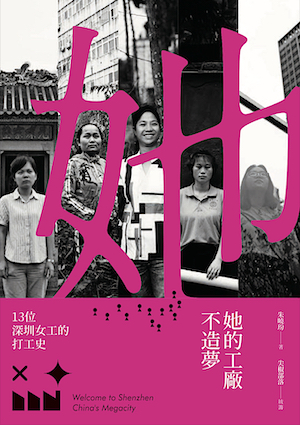

Source: Conflicting memories.

Ngaba is a prefecture in northwestern Sichuan, adjoining Golog prefecture, quite remote from Lhasa to the west. Demick puts in context the whole history leading up to the Chinese invasion and since, with vivid personal stories illustrating the successive cataclysms.

Part One begins with locals’ first traumatic encounter with Communist troops in the 1930s—the book’s title, referring to votive offerings eaten by famished Red Army troops on the early stages of the Long March, is borrowed from Li Jianglin and Matthew Akester (note When the iron bird flies). Demick goes on to outline the early years of the Chinese invasion after 1950, when the king of the Mei kingdom pragmatically accommodated with the new Communist overlords.

This is the back-story to the devastating assaults from 1958, told through the eyes of Gonpo (b.1950), the last Mei princess. After being evicted from their palace, she was relocated to the provincial capital Chengdu along with her mother and sister; her father, the former king, joined them after a year, traumatised after being held in solitary confinement. But the young Gonpo took readily to being sinicised, and was sent on to a prestigious high school in Beijing.

In the summer of 1966 she returned to Chengdu for a holiday with her family, but as the Cultural Revolution broke out she was soon summoned back to Beijing. Having shown willing in previous campaigns (indeed, she supported Chairman Mao avidly), Gonpo was now vulnerable. In 1967 she learned that her parents had died in suspicious circumstances. As she became a target of struggle sessions, a contingent of Red Guards from Ngaba demanded that she should be taken home for further punishment, but instead she was exiled to remote Xinjiang, labouring on a military-run complex in Qinggil (Qinghe) county near the Soviet border. Most of the population sent there were Han Chinese—including her kindly future husband Xiao Tu. They took part in the farm’s propaganda troupe, singing songs in praise of the Party’s “liberation” of Tibet. As higher education began to function again, Gonpo tried in vain to gain admission to colleges in Beijing and Shanghai.

When the couple got permission to take a holiday in 1975, Gonpo took Xiao Tu back to her old home in Ngaba, now unrecognisable; but despite her anxieties, the locals fêted her as a former princess. When they returned to Qinggil they held a simple wedding ceremony. On the death of Chairman Mao later in 1976, their main concern was that Xiao Tu would be able to avoid trouble by maintaining the dodgy loudspeakers broadcasting the funeral. As Demick notes, by the time she was writing Qinggil was the site of a “re-education camp”, inaccessible to outsiders.

We read the story of Delek (b.1949), who came from Meruma village just east of the prefectural capital, where people remained loyal to their former royal patrons. Since his family had suffered grievously as the Chinese enforced their power, he might seem an unlikely recruit to the Red Guards. Yet to many Tibetans the Cultural Revolution presented a welcome opportunity to challenge authority, and by 1968 Delek joined a branch of the Red Guards in Ngaba loyal to the Red City faction in Chengdu, supposing that they could now right the wrongs of the hated commune system and restore religious freedom. But as rebellion spread, the PLA were sent in.

Although this uprising was ultimately a failure, for six months the Tibetans had raised their own livestock, worshipped freely in the monasteries, chanted prayers, and conducted rituals. The monks had worn their robes. It had given Tibetans a taste of freedom, the memory of which could not so easily be extinguished.

In Part Two Demick describes the “interregnum” from the end of the Cultural Revolution to 1989.

By the time of Mao’s death in 1976, Ngaba was a ghost town, sullen and silent. A quarter century of Communist rule had destroyed far more than it had created. What remained consisted mainly of squat mud hovels in dun tones barely distinguishable from the ground underfoot. […] Dust and mud choked the streets. Gutters on either side served as open sewers and toilets.

With the monasteries demolished, there was little to alleviate the drabness or delight the eye. The market nurtured by the king that had made Ngaba worth a detour for traders was long gone.

Demick evokes the resurgence of market enterprise through the story of Norbu (b.1952), who was to become a leading entrepreneur in Ngaba. As a child he had been reduced to begging for the family by the Chinese “democratic reforms”, and later turned to the black market. By 1974 he was making regular trips by bus to Chengdu to buy goods that he could sell back in Ngaba. As the commune system crumbled, the range of merchandise increased. In partnership with his Chinese wife he opened a tea shop and a supermarket.

With the monasteries still closed, some monks also turned to business, with their higher level of literacy. The monasteries re-opened gradually from 1980. Of the roughly 1,700 monks at Ngaba’s main monastery Kirti, only around 300 were still alive; some were traumatised after years in prison. As in Chinese regions, many of those helping to rebuild the temples were former activists who had taken part in destroying them.

New buildings began appearing in the county town—dominated by the institutions of the Chinese state. Tibetans were keen to buy motorbikes, and the trade in caterpillar fungus made a lucrative boost to their income. Ngaba traders travelled not only to the booming southeastern Chinese cities but to Lhasa and the border with Nepal.

The Han Chinese population of Ngaba was growing too; as the Tibetan plateau became a promising place to make money, the state encouraged migration with Develop the West campaigns. Tibetans were soon outnumbered by Chinese in Amdo, and were disadvantaged in many spheres.

Still, Tibetan education was reviving (cf. the lama Mugé Samtan, whose initiative began in Ngaba as early as 1980—see Nicole Willock’s chapter in Conflicting memories, pp.501–502). Tsegyam (b.1964) was a young teacher at the Ngaba Middle School, which opened in 1983. He had been given a Tibetan education by (former) Kirti monks, and became fluent in Chinese, spending a period studying in Chengdu. During the wider cultural revival in the PRC he wrote poetry and essays for literary magazines. At the Middle School he cautiously added Tibetan culture into the curriculum.

Tsegyam’s eyes were opened by reading a copy of the Dalai Lama’s memoir My land and my people, brought back by a friend from a trip to India. As awareness of the Tibetan government in exile grew, major protests took place in Lhasa in 1987. Though there was a strong military presence in Ngaba, Tsegyam echoed the mood by pasting up posters in support of Free Tibet and the Dalai Lama. By 1989, as protests throughout the PRC gathered and were crushed, he was under interrogation; sentenced to another year in prison in 1990, on his release he was unemployed and unemployable.

We catch up with Gonpo. In 1981 she and her husband were permitted to leave Xinjiang with their two children, settling in Xiao Tu’s old home Nanjing. One of countless people whose past backgrounds were now forgotten, Gonpo did well as a primary school teacher. While she kept a small portrait of the Dalai Lama at home, she could pass for a Chinese—by now she could barely recall Tibetan.

Still, she received a visit from a high-ranking Tibetan official on a tour of Nanjing, who had her promoted to posts in the Party; though mainly ceremonial, her new status conferred benefits such as a comfortable apartment.

In 1984 Gonpo managed to arrange belated funeral rites for her parents at Kirti monastery. In Beijing she gained an audience with the Panchen Lama, also recently rehabilitated (see e.g. under Labrang 1); he encouraged her to study Tibetan culture in India, and with his help she set off there with her daughter in 1988 during a thaw in Sino-Indian relations. She intended to return to Nanjing in due course, but the crisis of 1989 ensured that she would now find herself living in exile in Dharamsala.

Part Three takes the story on to 2013, as tensions grew again. As urban China basked in McDonalds and Walmart, rural Tibetans still lacked basic amenities.

In Meruma, Dongtuk was born to a disabled single mother who overcame poverty. In her house was a shrine to her uncle, a tulku reincarnate lama.

What little that children knew about recent history was gleaned from their families.

To the extent that they were taught anything about Tibet in the 20th century, it was about how the Communist Party had liberated Tibet from serfdom. Their parents tended not to talk about it. Maybe they didn’t know about it themselves. Or they feared these stories of collective trauma might arouse anti-Chinese sentiments that could get the children in trouble later down the road. The surviving elders who knew firsthand—and who often carried the scars on their bodies—disgorged their memories only sparingly. If they hadn’t been half-starved and beaten, if they hadn’t languished in prison doing gruelling work, then they had done things of which they were now ashamed. You were either tormented or a tormentor. Nobody had escaped unscathed.

Dongtuk gladly accepted when his mother suggested that he become a monk at Kirti monastery, which was now expanding grandly. In the company of village friends there, he flourished at the monastery school. But a new policy was stamping down on monastic activism; a new “patriotic education” campaign was launched at Kirti in 1998, radicalising many monks. The school was closed in 2002.

Pema (b. c1965) was a supporter of the monastery. After the death of her husband she ran a market stall to support her children, two of whom were monks. She regularly took part in circumambulations at Kirti (cf. Charlene Makley for Labrang, ch.3). She took in a young girl called Dechen, who took to a Chinese education, as well as her niece Lhundup Tso, who was of a more enquiring mind. Pema herself was inclined to be grateful for the limited freedoms they now enjoyed. But she was concerned about a vast new construction project; while she felt more pity than hostility towards the Chinese, she didn’t want any more of them in her town. Infrastructure projects escalated in the buildup to the Olympics—along with surveillance.

Brought up in a nomadic community, Tsepay (b.1977) was not inclined towards dissent. His good looks gained him admission to an official song-and-dance troupe at the glossy resort of Jiuzhaigou, and at first he enjoyed the work. But he came to resent the condescending clichés intrinsic to such displays, and his comments got him into trouble. Leaving the troupe, he began travelling the plateau with cellphone and camera to document the transformation of the landscape.

Despite Chinese censorship, families and monasteries still commonly kept portraits of the Dalai Lama, although people were ready to conceal them if there was a raid. Tsepay listened to recordings of teachings by the Dalai Lama, and became aware of the conflict over the identification of the new Panchen Lama. In 2006, as the Chinese rhetoric against the Dalai Lama became more strident, Tsepay spent a year in prison for distributing Dalai Lama recordings, radicalising him further.

These stories come together in Demick’s account of the 2008 uprising. Serious protests broke out in Lhasa on 10th March on the anniversary of the 1959 uprising that led to the flight of the Dalai Lama. In Ngaba the military police were on full alert, but protests erupted there too on the 16th. Dechen normally found the troops rather dashing, but now the tension was clear. In the middle of a prayer festival at Kirti the young monk Dongtuk saw an older colleague holding up a photo of the Dalai Lama and yelling “Long live His Holiness the Dalai Lama!”. As other monks joined in, they swept out into the streets, confronting the riot police, who responded with tear gas and live ammunition. On their mobiles people began to learn of protests elsewhere in the region, in Labrang, Dzorge, and Rebgong.

Tsepay, on probation, couldn’t resist going into town. There he found the blood-stained body of a young Tibetan woman—probably Pema’s young niece Lhundup Tso. Pema, a curious onlooker, was horrified to learn that she was among those shot dead. Enraged, Tsepay entered the battle. Wounded, he escaped via Chengdu to Shenzhen, where he was pursued by police from Ngaba, but managed to escape again.

With Kirti monastery now under virtual siege, checkpoints, bunkers, and CCTV were installed. Nearly 600 monks were arrested, over a fifth of the monastery’s population. But the campaign to remove all traces of the Dalai Lama only increased the Tibetans’ reverence for him. At last Dongtuk could interpret the sufferings of his elders in terms of the current oppression. He began listening to illegal Amdo songs such as Tashi Dhondup’s 1958–2008 (see also here).

With Pema distraught over the death of her niece, and normal social life suspended, Dechen became the family’s go-between. Her education at Tibetan middle school had become more conventional; in response to campaigns against expressions of Tibetan nationalism, the students waged subtle protests.

Self-immolation

Life began returning to “normal” by the end of 2008, but the 2009 Monlam New Year festival prompted yet another crisis as a young Kirti monk set himself on fire on the main street. Though he survived, 156 Tibetans have since immolated themselves, of whom nearly a third came from Ngaba and nearby.

Dongtuk’s life at Kirti monastery had become tedious. He was a keen basketball fan, and loved watching movies. His mother eventually submitted to his repeated requests for her to muster the funds to allow him to study in India, but his efforts to leave were unsuccessful.

On 16th March 2011 another Kirti monk, a friend of Dongtuk, set himself on fire—this time fatally. Looking for scapegoats, police arrested monks, and locals rallied to protest. The monastery was barricaded again. But over the next months further self-immolations followed.

Ngaba was now sealed off and equipped with all the technology of riot control—with fire extinguishers now added to the police arsenal. When Demick visited the town in 2013 it reminded her of trips to war zones like Baghdad, Sarajevo, and the Gaza Strip.

As the self-immolations brought renewed international publicity to the Tibetan cause, the Dalai Lama and Tibet advocacy groups were in an awkward position.

Dechen, no longer so amenable to the Chinese, was now alienated by her education at school; Pema now began the complex procedures to help her reach India, as it became ever harder for Tibetan to gain travel permits. With Pema travelling as her chaperone, after a four-month journey they eventually made their way to Dham and crossed into Nepal.

Dongtuk too renewed his efforts to leave. He evaded attention by staying on his father’s nomadic pastures, getting to know his half-brother Rinzen Dorjee. And then, via Lhasa, Dham and Kathmandu, Dongtuk too managed to reach Dharamsala. As he resumed his studies at the branch of Kirti monastery there (founded in 1990), he learned of another self-immolation in Meruma—that of Rinjen Dorjee.

In Part Four Demick visits Ngaba refugees in Dharamsala, learning details hard to divulge in the intimidated atmosphere of Ngaba, and updating the story since 2014. (It is indeed possible for scholars to glean insights through extended stays among Tibetans within the PRC, as did Charlene Makley around Labrang, but in presenting their work they tend to be beset by academic concerns. For fine reflections on the differences between conducting research in Lhasa and Dharamsala, see Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy, “Easier in exile?“, cited in n.1 here).

The journey to India was always fraught with dangers. Following the initial exodus after 1959, another wave took place in the 1980s. We catch up with Gonpo, who had been in inadvertent exile in Dharamsala with her daughter since 1989. The Dalai Lama, whom she had met in 1956, received her warmly, giving her a post in the exile parliament. But as relations between the Chinese and the Dalai Lama deteriorated, Gonpo was unable to see her husband and her other daughter until 2005. As Demick observed after meeting her in 2014,

Not only does the rift between China and the Tibetans run straight through her family, it runs through her psyche. Gonpo loves China as well as Tibet. She still speaks better Chinese than Tibetan. More than most Han Chinese people I know, she absorbed the lessons of socialism. She eschewed conspicuous displays of wealth and was proud that she had shed her aristocratic roots and was, to use a Chinese Communist slogan, serving the people.

Goonpo was deeply disturbed by the self-immolations in her former home.

Demick also met the former Red Guard Delek, who had also managed to reach Dharamsala in 1989, becoming a historian as he documented the tribulations of Ngaba, while serving as caretaker at a school for young refugees.

The young teacher Tsegyam had sneaked across the border into India in 1992, eventually becoming private secretary to the Dalai Lama. And after fleeing Ngaba in 2008, Tsepay was on the run for four years, spending over a year in hiding on Wutaishan before reaching Dharamsala.

Dechen was enthusiastic about her studies at the boarding school run by the exile government; educating herself further by reading Woeser keenly, she was hoping to become a journalist. She took Demick to meet Pema, who despite her relief at escaping the appalling repressions in Ngaba, didn’t feel quite at ease, missing the material comforts of her former home.

Indeed, for many exiles the homeland remains ambivalent; with conditions in India less than ideal, they may be tempted to return to their homeland, despite the inevitable scrutiny to which they will be subjected. From a peak of 118,000 in the mid-1990s, the Tibetan population in India declined to 94,000 in 2009. The Chinese had plugged leaks to the borders, and Tibetans often move on to Western countries.

Demick considers the role of the Dalai Lama and current worries over the succession (for recent news, see e.g. here). The bar has lowered from independence to survival; but if the preservation of Tibetan culture sounds like a modest goal, even this can clearly not be taken for granted.

In her final chapter Demick ponders the limits of freedom. Some Tibetans even thought the Chinese had heeded the lessons of the self-immolations; they had cancelled an unpopular water diversion project, and shelved plans to house Chinese workers; aid projects were coming into effect. Photos of the Dalai Lama reappeared at Kirti. But Chinese migration continues, and Tibetans are still disadvantaged.

It should go without saying: The Tibetans are not some exotic isolated tribe trying to preserve an ancient civilisation against the advance of modernity. They want infrastructure, they want technology, they want higher education. But they also want to keep their language and their freedom of religion. […]

Time and again I heard the same story. Almost everybody was better off financially than they’d been a decade ago, like everybody in China. But Tibetans were still poor—even by the standards of rural China. And they could see that the Chinese newcomers in town had a higher standard of living.

Younger Tibetans might not be deeply religious; they might readily take to a Chinese education as a career path, and be seduced by the trappings of modern material goods. And yet they too have come to resent deeply their chronic submission to the Chinese, connecting it to the scars inherited from their elders, and they continue to fight to maintain their identity.

* * *

Eat the Buddha is based on three trips to Ngaba, as well as interviews with Ngaba people elsewhere, most fruitfully in Dharamsala.

With a few exceptions […], the people in this book left Tibet not for political reasons but to further their education or personal growth.

For the most part, they were regular people who hoped to live normal, happy lives in China’s Tibet without having to make impossible choices between their faith, family, and their country.

As she did for Nothing to envy, Demick provides a useful research guide in a section of endnotes, themed by chapter. Besides her own visits to Ngaba, Chengdu, Lhasa, and Dharamsala, she cites sources such as the War on Tibet site of Li Jianglin and Matthew Akester, the work of scholars such as Tsering Shakya, Robert Barnett, and Melvyn Goldstein (we can now add Conflicting memories, including Bianca Horlemann’s chapter 11 on Golog), as well as human rights groups (cf. my roundup of posts on Tibet). Tsering Woeser has written on self-immolation in Tibet on fire (2016), and in this article. Many of these issues are covered on the excellent High Peaks Pure Earth website.

While the Chinese Party-State’s repression of the Tibetans is taking a rather different form to its barbarity in Xinjiang (see this roundup of posts on Uyghur culture), it’s important to keep the Tibetan case in the public eye. Over seventy years of Chinese indoctrination and brute force have been ineffective; a way out of the impasse remains elusive. Engagingly told through personal stories, Eat the Buddha makes a microcosm of the travails of Tibetans in their sorry encounter with the modern Chinese state, serving for the non-specialist (that’s me) as a digestible introduction to complex issues.

* For some effective popular works on other areas, see Charles King (here and here), Undreamed shores, Watching the English, and The souls of China.

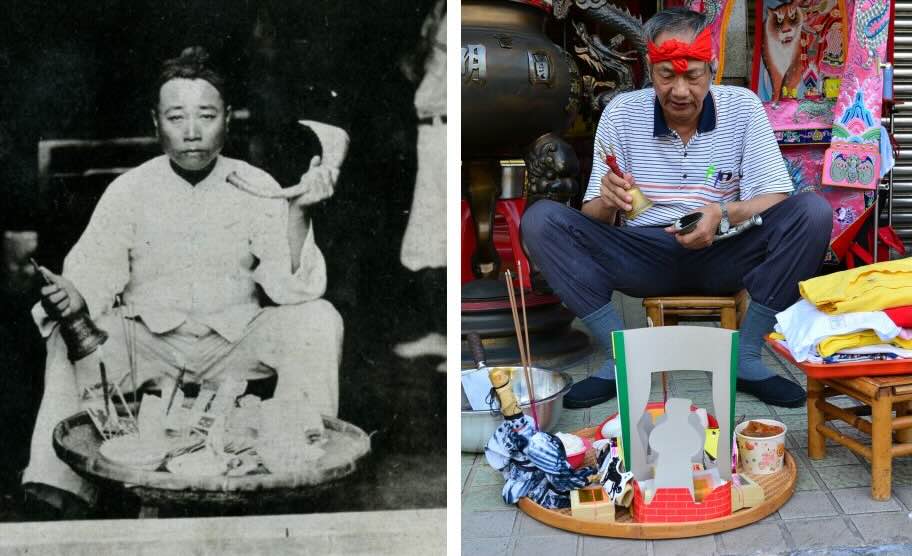

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual:

Scene from the Great Improvement of Luck ritual: The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

The Wei Yuan Altar 威遠壇 in suburban Taipei,

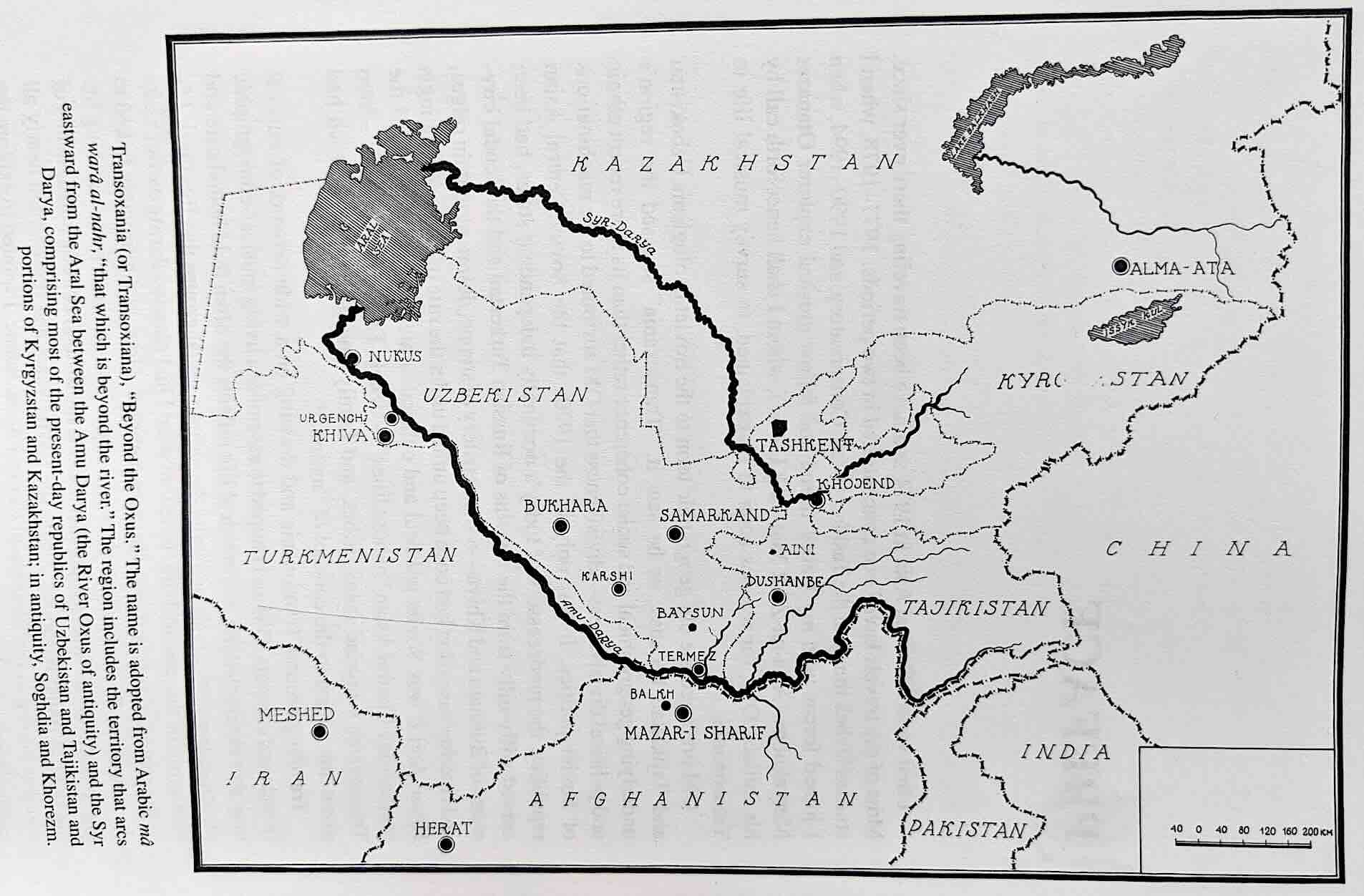

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

From The hundred thousand fools of God.

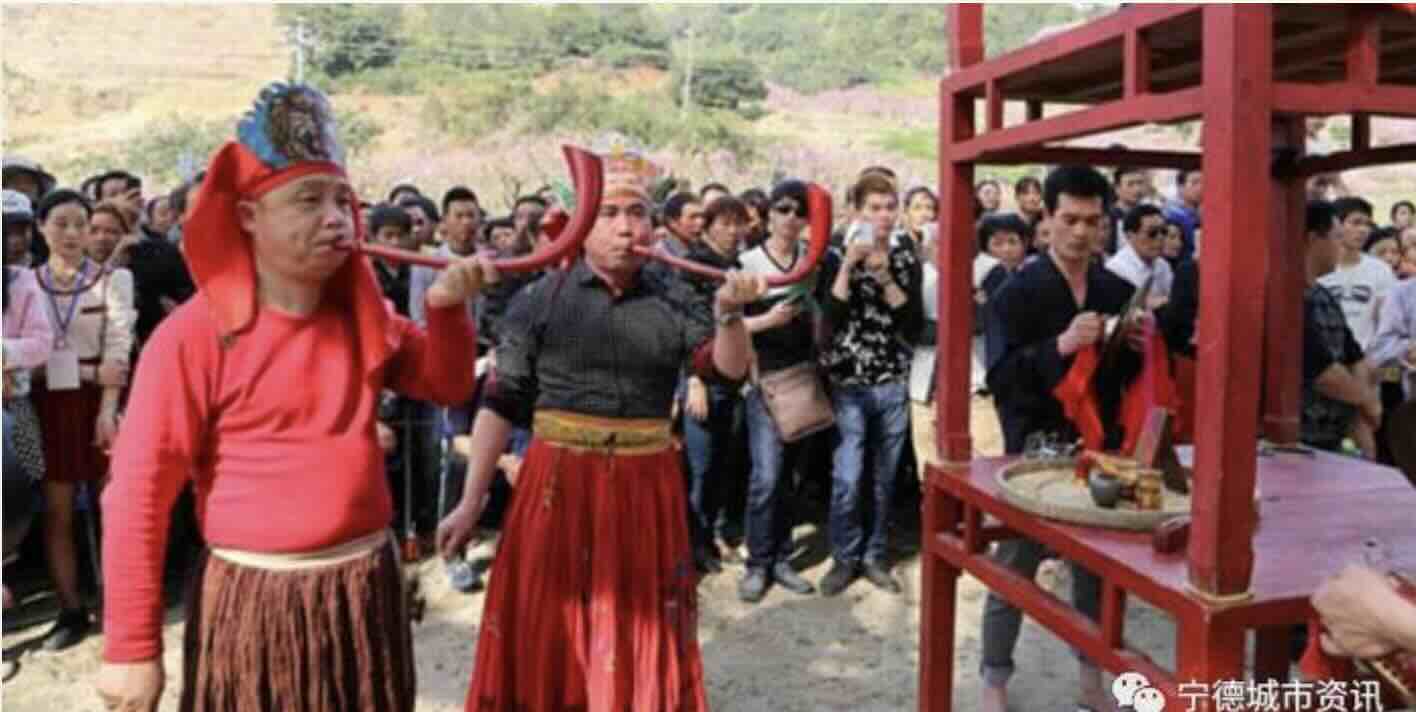

Biographies of Pingtan paizhi master Wang Shanglong and Chen Renzhen.

Biographies of Pingtan paizhi master Wang Shanglong and Chen Renzhen. The Qinghe guan society in Changtai.

The Qinghe guan society in Changtai.

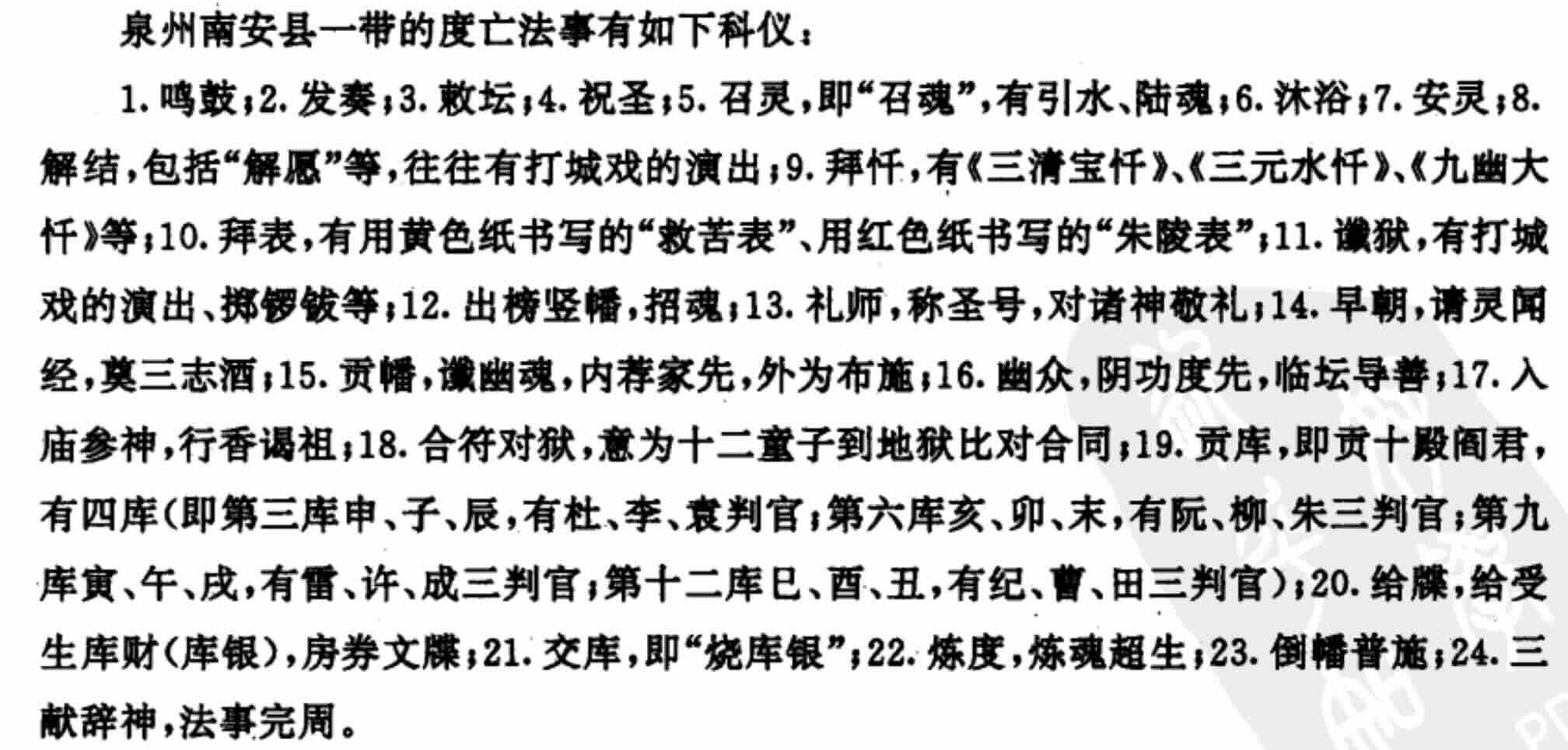

Household Daoist rituals, Putian.

Household Daoist rituals, Putian. Segments of mortuary rituals, Nan’an (again, cf.

Segments of mortuary rituals, Nan’an (again, cf.

Hofmann also remarks, rather too sweepingly, that

Hofmann also remarks, rather too sweepingly, that

From Blue kite (Tian Zhuangzhuang, 1993).

From Blue kite (Tian Zhuangzhuang, 1993).

Plan of Lhasa, 1904, by L.A. Waddell.

Plan of Lhasa, 1904, by L.A. Waddell.

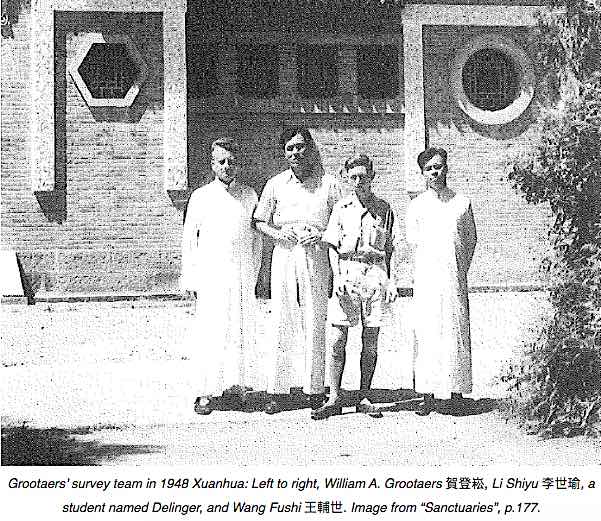

With the Mayor of Philadelphia.

With the Mayor of Philadelphia. Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Mother Divine signs her book for Li Shiyu.

Original caption (

Original caption (

The shop in Chalk Farm.

The shop in Chalk Farm.

Born in 1979 in the port of Durrës just west of Tirana, Lea was prudently brought up to revere Uncle Enver and Stalin—despite the complicated “biographies” of her family, which she only began to understand later.

Born in 1979 in the port of Durrës just west of Tirana, Lea was prudently brought up to revere Uncle Enver and Stalin—despite the complicated “biographies” of her family, which she only began to understand later.

Sola is one of three children of

Sola is one of three children of

After graduating, partly in rebellion against the establishment that contemporary Western Art Music seemed to represent, Sola chose to become a pop musician, giving concerts and composing for film soundtracks, TV, and theatre. At the same time she made a great impression with her 1985 novellas Ni biewu xuanze 你别无选择 (You have no choice), Lantian lühai 蓝天绿海 (Blue sky green sea), and Xunzhao gewang 寻找歌王 (In search of the king of singers). Her voice was

After graduating, partly in rebellion against the establishment that contemporary Western Art Music seemed to represent, Sola chose to become a pop musician, giving concerts and composing for film soundtracks, TV, and theatre. At the same time she made a great impression with her 1985 novellas Ni biewu xuanze 你别无选择 (You have no choice), Lantian lühai 蓝天绿海 (Blue sky green sea), and Xunzhao gewang 寻找歌王 (In search of the king of singers). Her voice was

From The afterlife of Li Jiantong.

From The afterlife of Li Jiantong.

The golden age of the MRI, 1954:

The golden age of the MRI, 1954:

Pu Xuezhai, early 1960s.

Pu Xuezhai, early 1960s.

Cecilia Lindqvist studying with Wang Di, 1961.

Cecilia Lindqvist studying with Wang Di, 1961.

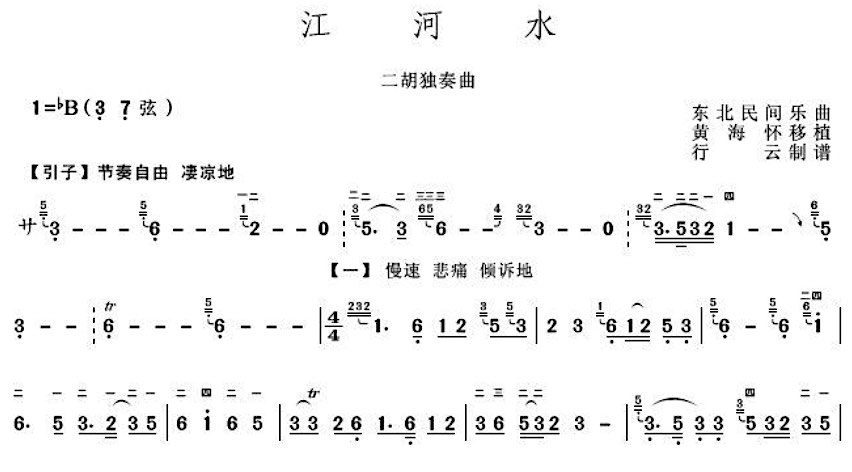

Opening of Guangling san:

Opening of Guangling san:

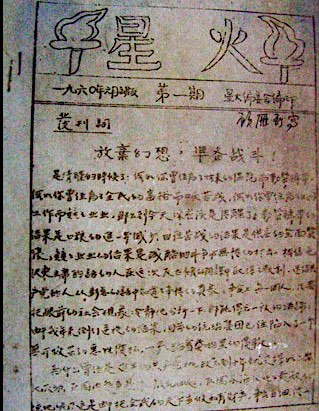

Even for the period since the 1980s’ reforms there is plenty of folk memory for the Party-State to repress (see e.g.

Even for the period since the 1980s’ reforms there is plenty of folk memory for the Party-State to repress (see e.g.