- Charles King, Midnight at the Pera Palace: the birth of modern Istanbul (2014)

is just as compelling as his book on the Boas circle of anthropologists.

For reviews, see e.g. here; and Pheroze Unwalla makes pertinent comments, opening with reflections on “popular history” and its deservedly growing popularity.

The Pera Palace hotel was established in 1892 to service clients arriving on the Orient Express in the capital of the Ottoman Empire, in what was then Istanbul’s most fashionable neighbourhood. King evokes

the Muslim foundation that first owned it, the Armenians who marked it out for development, the Belgian multinational firm that made it famous, the Greek businessman who bought and lost it, and the Arab-born Turkish Muslim who guided it, somewhat the worse for wear, through the Second World War.

But while the hotel is a recurring theme, he doesn’t belabour it as metaphor.

Istanbul was settling into a self-absorbed sense of hüzün, the hollowed-out melancholy that Turkish intellectuals said infused the crumbling walls, tumbledown mansions, and rotting seaside villas.

Among King’s inspirations was the photography of Selahattin Giz (1914–94) (some instances shown below); often he views the city through the prism of Western visitors.

Europeans who came to Istanbul understood the dark side of their own civilisation precisely because many of them were its victims. After the First World War, in the parallel universe created by the collapse of empires across Europe and the Near East, Westerners were sometimes the needy immigrants and Easterners their reluctant hosts. Wave after wave of Europeans landed in Istanbul in ways they could never have imagined—not as conquerors or bearers of enlightenment but as the displaced, impoverished, and desperate.

The city had long suffered regular earthquakes and fires; firemen commonly exacerbated the damage. Amidst a changing physical landscape, Istanbul constantly reinvented itself—as cities do.

Ethnic cleansing is a major theme. As the Ottoman empire crumbled, forced and “voluntary” migrations took place, with Muslim migrants seeking refuge from the warfare of southeast Europe. On the eve of World War One, the city was estimated to have around 977,000 dwellers, of whom 560,000 were Muslim, 206,000 Greek Orthodox, and 84,000 Armenian Christian; nearly 130,000 were foreign subjects, mostly non-Muslim.

Greeks, Armenians, and Jews had long been an intrinsic part of the city’s fabric. Istanbul had been something of a haven for the latter groups:

In this complicated world, an Armenian family might be Catholic, Protestant, or Apostolic Christian. They might profess deep loyalty to the sultan or work secretly on behalf of a national liberation movement, which in turn might lean in either the liberal direction or the socialist one. They might be subjects of the sultan or enjoy citizenship of another country, even if they had lived in the city for generations. Jews were likewise divided among the Sephardim, descendants of immigrants from Spain, and the Ashkenazim of eastern Europe, who moved into the city in increasing numbers in the 19th century. Each might in turn identify as Zionists, socialists, or liberals, and as either Ottoman subjects or foreigners.

After Greek troops occupied the coastal city of Smyrna/Izmir in 1919 Turkish forces brutally retook it in the “Catastrophe” of 1922. Meanwhile Mustafa Kemal was consolidating Turkish nationalist power before proclaiming the Republic in 1923.

In the Allied occupation following World War One and the Armenian genocide, British, French, and Italian troops oversaw zones of control. The commentator Ziya Bey evoked the post-war Pera Palace, under its Greek proprietor Bodosakis:

Foreign officers and business men are feted by unscrupulous Levantine adventurers and drink and dance with fallen Russian princesses or with Armenian girls whose morals are, to say the least, as light as their flimsy gowns.

Istanbul’s non-Muslim minorities fell from an estimated 56% in 1900 to 35% by the late 1920s. During the war the general population of the city shrunk, with many seeking refuge elsewhere. Still, it was now home to substantial populations of displaced Muslims, as well as Armenians who had fled the warfare in Anatolia.

And King goes on to describe the presence of “desperate and resourceful” Russian refugees fleeing the revolution there—again representing a variety of political persuasions and economic circumstances. Until they began moving on in the 1920s, to some observers Istanbul even seemed like a Russian city. The American Thomas Whittemore led relief work on behalf of these new refugees.

The new bureaucratic labels of “Greek” and “Turkish” were clumsy.

A Greek Orthodox family might speak Turkish and have roots in the same Anatolian village extending back many generations. A Greek- or Slavic-speaking Muslim in Greece might similarly have had little in common with the culture of the Turkish Republic. But in the exchange, the former was declared a Greek and the latter a Turk, with both shipped off to a foreign but allegedly co-ethnic home.

Even the city’s Armenian community could still survive, “especially if one avoided politics, spoke only Turkish in public, and embraced silence as a way of dealing with the past”.

And Istanbul’s nightlife continued to thrive. King describes the jazz age and the film industry. I think of Shanghai, subject of much research (such as Andrew Jones, Yellow music) and nostalgia.

Frederick Bruce Thomas. Source.

Whereas the traditional meyhane taverns had offered food and alcohol, the new clubs added modern entertainment (note Batu Aykol’s fine film on the history of jazz in Turkey). The “sultan of jazz” was Frederick Bruce Thomas, whose club Maksim’s enjoyed a brief heyday. Russian dancers trained a generation of Istanbullus; the Charleston was (ineffectually) banned, “not because it offended Muslim sensibilities, but because record numbers of people were being admitted to the hospital for sprains and bruises”.

The “black eunuchs” of the former imperial harem sought to alleviate their reduced circumstances by forming a mutual-assistance society and putting to use their antiquated, refined etiquette.

“Black eunuchs” at a meeting, late 1920s/1930s.

Passing swiftly over King’s rash claim that “there is no well-developed field of study called sonic history” (“I’m like, hello?”), we read of the changing soundscape of Istanbul, including motorcars, organ-grinders, and sirens. King notes karagöz shadow puppets, precursors of the movies. Foreign films were eventually supplemented by a Turkish industry; as elsewhere, film could serve as a vehicle for state propaganda.

As the recording industry took off, the phonograph was ever more common among middle-class families.

In the past, the fame of professional musicians had been limited by geography. Musicians might be highly regarded in a particular neighbourhood or sought out for a wedding or another celebration across town, but national or international acclaim was hard to imagine. Now an audience could love someone they had never met and cry at a song they had never heard performed live. […]

It was now possible to remember, even pine for, a specific and imagined world at the exact moment when it seemed to be slipping away into the irretrievable past. There was little specifically Ottoman about these memories, at least not in the sense of thinking wistfully about sultans, harems, and the recumbent life of pashas and beys…

If jazz, and clubs like Maxim, catered for the more well-to-do, the pulse of the demi-monde was a more gritty popular music (to which I devote a separate post). What were known in Greece as rebetika songs expressed both nostalgia and pain; narcotics were both a stimulant and a theme. Ethnic minorities and women were prominent on this scene. King provides vignettes on Roza Eskenazi, Hrant Kerkulian, and Seyyan—respectively Jewish, Armenian, and Muslim; “had it not been for the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, their lives might have been mapped out mainly within the confines of those religiously defined communities”. Such performers now achieved stardom through the new recording industry, bolstered by migration.

Roza Eskanazi’s family had moved from Istanbul to Salonica, and by the early 1920s she moved on to Athens, becoming an early star of rebetika. The blind oud-player Hrant Kerkulian, known as Udi Hrant, remained based in Istanbul. Seyyan Hanım was one among a new group of Muslim women (also including Safiye Ayla) who dared take to the stage, becoming famed for her renditions of tango.

King ends the chapter by introducing the two enterprising migrant families. The Zildjians, from an Armenian background, had long supplied cymbals to Ottoman military bands. Having fled the violence for the USA around 1915, they were back in Istanbul by the 1920s, still making cymbals—now largely for the export market, since the Ottoman bands were in decline. But they returned to the States, setting up a prosperous business in Massachusetts for the thriving jazz scene. And the Ertegün brothers, sons of a Turkish diplomat based in Washington DC, went on to launch Atlantic Records in 1947.

Meanwhile in Istanbul, the writer Fikret Adil linked the decline of the jazz scene to government restrictions on the sex trade in 1930.

By 1934 Mustafa Kemal was Atatürk, father of the nation, with its capital of Ankara. While he kept a tight rein on dissent, armed uprisings were common in east Anatolia. In a secular republic, religion was controlled, including Sufi groups like the Alevis. The ezan call to prayer was amplified from 1923. “Turkishness” was effectively propounded. While the Republic stressed modernity and progress, 97% of the country’s land area was in poor, sparsely-populated Anatolia. “The Turkish mind may have shifted west, but the Turkish state had shifted east”. The 1927 national census for greater Istanbul listed around 448,000 Muslims, 99,000 Orthodox Christians (mainly Greeks), 53,000 Armenians, and 47,000 Jews, making it the only place in the entire republic with a sizable minority presence.

An important chapter follows on the lives of women. “For Muslim women, the creation of the secular state was often said to have ushered in liberation from the double yoke of tradition and religion”. Legal rights were instituted in property inheritance, divorce, franchise, and the abolition of polygamy.

Women were by and large written into the new republic’s history but written out of it as individuals. When they did appear, it was usually as cardboard heroines, women who sacrificed themselves for the nationalist cause or took up patriotic professions in service to the republic. […]

Like much of Kemalism, however, the world did not change suddenly with the proclamation of the republic, nor did the gains achieved by women erase old social habits. […]

Turkish politicians sometimes claimed that women themselves were the main obstacles to female progress. Burdened by their own narrow horizons, they were simply failing to take up the new opportunities afforded them by changes in the civil code.

Portrait of Halide Edip by Alphonse Mucha, 1928. Source.

A prominent early Turkish feminist was Halide Edip (1884–1964). Working as an essayist from 1908, she went on to side with the nationalist agenda of Kemalism, but later took issue with its broken promises and increasing authoritarianism. In 1926 she went into self-imposed exile, only returning after Kemal’s death in 1938.

Another thorn in the side of the new regime was the author Nâzım Hikmet (1902–63), whose socialist leanings inclined him towards the Bolsheviks (see also here, and here).

Bolshevik Russia and Turkey did have certain things in common. Both stressed the role of the state as the engine of social and economic transformation. Both countries had forsaken the multiparty parliaments that the Romanovs and Ottomans, for all their faults, had managed to create in their final years. They eventually took for granted the view that statism—the government’s careful managing of the economy and society—worked best when societal transformation was handled by a single political party, the Communist Party in the Soviet Union and the Republican People’s Party in Turkey. […]

Turkey, however, was a country without a proletariat. Because of the loss of so many urban centres, from Salonica to Damascus, the new republic was even more rural than the Ottoman Empire. In Russia—itself overwhelmingly rural—Lenin and Trotsky had already shown that workers were not essential components of a workers’ revolution. All that was required was a small group of conspirators who could form a party, seize the state, defeat the backers of the old regime in a civil war, and then set about building, through industrialisation and radical land reform, the very proletariat that they claimed as the base of their support.

But the two revolutionary regimes were in conflict. Nâzım Hikmet’s flirtations with Moscow led to extended periods in prison, from where he continued writing. Returning to Moscow after his release, “his literary voice became that of the wizened ex-prisoners, not the firebrand poet of earlier years”.

“Perhaps the most reluctant visitor ever to arrive in Istanbul” was Leon Trotsky. Reaching the city in 1929 with his wife Natalya after a 3,000 mile train journey from Kazakhstan to Odessa, he was to be under close surveillance. Their home on the island of Büyükada always felt insecure, with a real threat of assassination. The radical American poet Max Eastman acted as Trotsky’s literary agent, finding him to be preoccupied with mundane financial concerns.

During Eastman’s visit, Trotsky spent most of their time together trying to convince Eastman to collaborate on a stage play about the American Civil War. Trotksy believed it would be a hit on Broadway, a work that would combine Eastman’s knowledge of American history with his own expertise on troop movements and tactics. Eastman considered the idea ridiculous.

Trotsky’s repeated applications for foreign visas were constantly rejected until he managed to gain asylum in south France in 1933, ending up in Mexico. Throughout the whole period Istanbul was a hotbed of espionage. Among the cadre of Soviet agents was Leonid Eitongon, who had served in Harbin in northeast China, then a kind of East Asian version of Istanbul (see under Robert van Gulik). In 1940 Eitongon pursued Trotsky to Mexico, grooming Ramón Caridad to murder him.

In 1929, just as Trotsky was arriving in Istanbul, Yunus Nadi, a former colleague of Halide Edip who became a leading publicist for the new regime, announced the nation’s first ever beauty contest, to “demonstrate the elevated qualities of the new republican woman to a global audience” (Discuss…). But three years of contests failed to produce an international winner—the 1930 Miss Europe title went to the entrant from Greece, a blow to Turkish national prestige.

Keriman Halis. Source.

With conservatives suspicious of loose morals, in 1932 Yunus Nadi sought out Keriman Halis, whose virtuous pedigree was beyond reproach. In a triumph for Turkish national prestige, she promptly won the Miss Universe contest, splendidly known as the International Pageant of Pulchritude (cf. the Judgment of Paris, under Pomodoro!). Her fame eclipsing that of Halide Edip, she became a symbol of Kemalist virtue, insisting that the contest had been an exhibition of female emancipation and Turkish modernity.

The rivalry with Greece introduces a chapter on the contested site of Hagia Sophia/Ayasofya. As a Christian cathedral it was a magnificent symbol of Byzantine Constantinople from the 6th century. Long before its conversion to a mosque upon the Muslim conquest of 1453, the 8th-century Iconoclast movement had defaced human images in such churches. When the Swiss Fossati brothers were invited to refurbish the site in the 1840s they briefly uncovered rich early layers.

We now meet the philanthropist Thomas Whittemore again; in his role as founder of the Byzantine Institute in the 1930s, he raised funds for a major new restoration project that entailed making the building into a museum, gaining official permission largely through Turkey’s new rapprochement with Greece. As the archaeological team uncovered old mosaics, the site was revealed as “colour-filled, majestic, and a hybrid of East and West in exactly the way that Mustafa Kemal’s republic was imagining itself”. While conservatives railed against reviving the mosque’s infidel past, others felt that “the artistic glories of the city were being freed from their religious veils and revealed to their secular custodians”. The restoration attracted great international publicity.

For centuries the most important building in the city had been a place of Islamic worship, accessible to the faithful but generally hidden from non-Muslims. Now it was open to everyone.

The long-running dispute, and the building’s use as a political pawn, continues today. Among a wealth of discussion, see e.g. this 2013 article by Robert G. Ousterhout. The re-conversion to a mosque in 2020 has been widely deplored, e.g. by the Italian Association of Byzantine Studies, and Ipek Kocaömer Yosmaoğlu.

In the spring of 1939 Joseph Goebbels was impressed by a visit to Hagia Sophia.

The last three chapters discuss Istanbul during World War Two, as Turkey strove to remain on the sidelines of the conflict between foreign powers. Following the death of Atatürk in 1938, Turkey was itself in a period of political turmoil. Espionage intensified, with the Turkish Emniyet secret police active alongside foreign agents.

In March 1941 several were killed when a suitcase bomb exploded at the Pera Palace.

Turkey was ever more vulnerable when the Wehrmacht launched its Balkan campaign in April–May 1941 and invaded the Soviet Union in June.

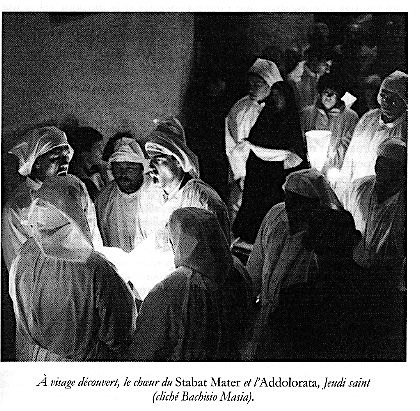

Jewish refugees, probably survivors of the doomed Mefküre convoy,

arrive at Sirkeci station from the Black Sea coast.

Efforts increased to rescue Jews from occupied Europe. In February 1942 nearly 800 Jewish families stranded aboard the Struma, anchored off the coast as they hoped to gain passage to Palestine, lost their lives in a massive explosion. By 1944 Ira Hirschmann, with US government support, was leading rescue efforts in Istanbul, working closely with the well-connected Chaim Barlas from his base at the Pera Palace to negotiate labyrinthine bureaucracy. Meanwhile the Turkish press printed antisemitic cartoons, and a wealth tax, though short-lived, squeezed minorities further. Despite the otherwise dubious wartime record of the Roman Catholic church, in 1944 Archchishop Roncalli (who became Pope John XXIII in 1958) played a major role in rescuing Hungarian Jewish refugees.

In the Epilogue King can only outline the later story. In 1950 the one-party system was dismantled with the Democratic victory over the Republican People’s Party that Atatürk had founded. In 1952 Turkey became a member of NATO; but in 1955 another pogrom against Greeks, Armenians, and Jews soured the mood—the last straw for Istanbul’s minorities. Military coups followed in 1960, 1971, and 1980.

King reflects on the tensions between the national and elegiac modes of writing modern European history:

Both are, in their way, fictions. National history asks that we take the impossibly large variety of human experience, stacked up like a deck of playing cards, and pull out only the national one—the rare moments in time when people raise a flag and misremember a collective past—as the most worthy of our attention. The elegiac asks that we end every story by fading to black, leaving off at a point when an old world is lost, with a set of ellipses pointing back toward what once had been.

His engaging style is a model of popular history—in the best sense.

This is the start of an ever-growing series of posts on Turkey, west and central Asia, rounded up here.

The roster of early American humorists commonly begins with

The roster of early American humorists commonly begins with