I much admired

- Frances Larson, Undreamed shores: the hidden heroines of British anthropology (2021).

It’s just as engaging as Charles King’s book on the Boas circle in the USA, bringing to life the struggles of the unsung early generations of enterprising women intrepidly setting forth from Oxford in the early 20th century.

Writing from her own self-confessed armchair there, Larson opens by noting that by our time anthropology has no longer been limited to the study of distant shores:

One of my contemporaries decided to study local church bell-ringers; another explored the world of online video-gaming communities from the comfort of the college computer room; and I travelled into the past.

That given, she shows a remarkable empathy for the five female explorers who are the subject of her book. For Turkey, see Following Miss Bell.

Oxford was far ahead of Cambridge or the LSE in training female anthropologists. Yet before World War One, women at the university

were almost entirely invisible, frequently disdained, and usually inconsequential to the men they studied alongside. […]

Fieldwork offered these women a temporary relief from the strictures of English society, or at least it offered a new context—a new place, a new culture—in which to negotiate their own identity. […]

They went from the periphery into the unknown, and I doubt that any of them felt fully at home in England again. Instead, on their return, they fought for recognition in a university system ruled by men, and their professional aspirations strained their personal relationships.

Larson highlights the gender imbalance in funding; by contrast with the hoops through which the women seeking support had to jump, their male counterparts

were simply given a cheque and sent off on their travels in eager anticipation of the treasures they would undoubtedly find. They enjoyed a far freer rein and did not have to concern themselves with any references, résumés, or research plans.

And unlike the women, the men could confidently look forward to a permanent university position as reward for their explorations in the field. For all that, Larson gives due credit to the male patrons who encouraged their students—just as the movement for female suffrage was taking hold.

Katherine Routledge and the Kikuyu

Larson begins with Katherine Routledge (1866–1935) and her 1906 journey to British East Africa. It was already a bold step for her to escape the “dreary domesticity” of an affluent provincial life in Darlington by applying to read History at Oxford university in her mid-twenties.

Educating women was considered radical, subversive, even dangerous, by the many in middle-class England who thought that it risked undermining women’s true calling as wives and mothers. An education, it was argued, would render them either unwilling or unfit for their domestic duties. It might damage their feminine constitutions, which were too frail and too too irrational for the rigours of academic study. […]

To get around these prejudices, the first women’s colleges at Oxford were presented as harmless finishing schools.

After university Routledge spent a few unhappy years teaching at Darlington Training College before moving to London, where she became involved with the South African Colonisation Society. In 1905, after a trip to South Africa, she met William Scoresby, a “colonial drifter”, in London. In British East Africa, at the frontier outpost of Nyeri (a six-day trek from Nairobi), he had already begun to document the Kikuyu people—who “matched the anthropologist’s ideal of a ‘primitive culture’ perfectly”. After marrying in 1906 they resolved to make their home there. Though they were untrained, it was still unusual for anthropologists to spend a year in the field.

But by the time they returned to London in 1908, their relationship was suffering. Their book on the Kikuyu was published in 1910, with their individual contributions carefully noted. As she observed, “there is work which, if it is to be done properly, must be done by a woman”. And in a similar vein to her counterparts in the USA, she “revelled in the opportunity to disrupt British middle-class assumptions” about gender relationships.

This led to an invitation for Katherine to enrol for Oxford’s recently-established diploma in anthropology, headed by Robert Marett. She was among four women and nine men who took the course in 1911. Women were less likely than men to be concerned about their future earning potential, and anthropology was an “intrinsically egalitarian subject”.

Maria Czaplicka

Among the new students was Maria Czaplicka (1884–1921). From a poor background, with Warsaw dominated by Russian culture, in order to gain a Polish education she had attended the Flying University, an illegal underground organisation. By 1910, in her late twenties, she won a scholarship from the Mianowski Fund to come to England.

She first attended seminars at the LSE, where Bronislaw Malinowski was her fellow student. With no family outside Poland, Czaplicka soon took to Oxford life, despite the considerable effort that went into making women invisible there: after the more relaxed social life of London, she found the “sex apartheid” strange. Vera Brittain, who arrived at Somerville in 1914, wrote that Oxford was “deeply attached to its standards of scholarship and totally indifferent to ugliness and dowdiness” (and do read her Testament of youth).

As well as taking tutorials with Marett, the new intake attended lectures by Henry Balfour, curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum, and Arthur Thompson, professor of human anatomy.

Barbara Freire-Marreco and New Mexico

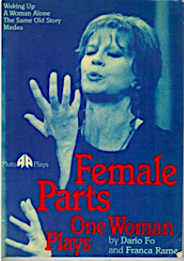

In 1911, for the first time, a woman gave a series of lectures for the anthropology students. Barbara Freire-Marreco (1879–1967) came from an affluent background in Woking; after studying Classics, she had taken the anthropology diploma in 1908. As she observed, there was a dangerous division of labour between “literary anthropologists” and amateur observers abroad: half the people had no first-hand experience and the other half had no training.

In 1910 Freire-Marreco had already spent eight months doing fieldwork in New Mexico, joining a camp run by the American School of Archaeology near the Rio Grande. At first she struggled

to find a suitably “savage” people to study: some were not savage enough, others were too savage, and none were particularly willing to talk.

As she learned the Tewa language, she made a base at the pueblo of Santa Clara. But

they were not about to open their hearts to an Englishwoman simply because she asked politely.

These settlements had long suffered from colonial intrusion, beset by the usurpation of their land, disease, the influx of settlers, the railroad, and assimilationist policies (see under Native American cultures).

Even as Native American culture was under assault, some settlers were engaging in a nostalgic search for the “old New Mexico”. The brief of team leader Edgar Hewett illustrated the irony:

His genuine academic interest and his desire to share information about pueblo culture also threatened to debase it. Pueblo people knew, from long and painful experience, that the only way to protect their beliefs was to keep them secret.

In leafy Woking, Freire-Marreco’s family had employed a cook, a parlourmaid, and a housemaid; in Santa Clara she now learned the pleasures of fending for herself. Still, she

did not expect her work to be so slow, or so circuitous, and she quickly experienced the fear that every anthropologists feels in the field: that she would have nothing to show for her time abroad. All the lofty theories that she had read at Oxford, about collective psychology and comparative religion and the history of political institutions, seemed reduced to nothing in this world of housework and preserving fruit. But she knew that doing things with people, and sharing their everyday lives, although slow as a research technique, was more reliable than simply asking people to describe themselves.

Noting the role of the paid “informant”, Larson describes the ambivalent help that Freire-Marreco received from Santiago Narenjo, a prominent local activist. He kept hidden from her the rituals that had gone underground under long-term Christian missionising; but then her casual mention of a green parrot to one of the villagers opened up a seam of enquiry. Parrot feathers were essential to the religious dances of Santa Clara, but in short supply. Freire-Marreco now sent a flurry of letters to her contacts in the USA and England requesting parrot feathers.

Describing English life to her hosts, she found herself the object of anthropological enquiry:

She knew that the limited understanding her new friends had of fox hunting, from her inadequate explanations and their unfamiliar reference points, was hardly more reliable than her understanding of their complex cultural traditions.

Much as she enjoyed the whole experience, it gave her a suitable diffidence.

Maria Czaplicka in Siberia

Larson now turns to Maria Czaplicka’s extraordinary Siberian expedition in 1914–15. Having written unsuccessfully to the Smithsonian for a job there, she was engaged by Marett on a project to work on the ethnography of Siberia, with financial help from Emily Penrose at Somerville. First, Czaplicka could interpret the plentiful Russian research on the topic; having published a preparatory survey of this literature, she was ready to gain first-hand experience.

After the usual lengthy search for further funding, she now chose to live among the nomadic reindeer herders of north-central Siberia, working with the American Henry Hall, who had also studied at the LSE; on the first leg of the journey they were also accompanied by ornithologist Maud Haviland and illustrator Dora Curtis. Via Moscow, they took a five-day trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway (completed in 1904) to Krasnoyarsk, and then embarked on a three-week voyage by steamboat north on the Yenisei river.

Travelling by sledge between chum family tents in this desolate landscape, they faced daunting hardships. The indigenous Evenks found Czaplicka most perplexing:

She carried so much paper around with her and yet she seemed to know so little about the workings of the world: she could not even get the marrow out of a reindeer bone to eat. Why did she ask so many questions and why did she travel in such dreadful weather, when all sensible people stayed safe inside their chum?

Again, she found herself the object of the locals’ anthropological enquiries.

In letters that reached them after several months, they learned of the imminent outbreak of war. Czaplicka was particularly anxious for her family in Poland. As she described in her book My Siberian year (1916), along the way she also met political exiles from Russia and Poland, including both professionals and “gamblers, drunkards, thieves, and degenerates”. She joked about her own “voluntary exile”. But

Siberia had a strange levelling effect on its population: gentlemen, savants, and criminals all became “peasants”.

By June 1915 they were back in the “relative metropolis” of Krasnoyarsk, collecting artefacts in the surrounding region. In July they set off for England by way of Moscow.

Katherine Routledge on Easter Island

Meanwhile Katherine Routledge and William Scoresby had embarked on a voyage to Easter Island in 1913; arriving more than a year later, they stayed until 1915. Routledge’s time there was far from the liberation that Czaplicka had experienced. The claustrophobic year-long voyage put their marriage under further strain; and they soon found that Easter Island (annexed by Chile in 1888) was no tropical paradise.

Greeted by Percy Edmunds, the English manager of the only farm Mataveri, they soon learned of the island’s troubled past: shipwrecks, persecution, uprisings, and disease.

The history of the island’s extraordinary giant stone statues had already been the subject of speculation. Routledge and Scoresby undertook a survey of the architectural heritage—while following in the tradition of plundering it. Routledge worked closely with Juan Tepano, a foreman at Mataveri, exploring oral accounts of the island’s culture.

But the population was still troubled, and discontent was brewing. As the female prophet Angata instigated raids on the farm, violence threatened to escalate. The explorers pinned their hopes on the arrival of the Chilean navy; but when they eventually reached the island, rather than punishing the locals they mollified them.

The crisis somehow averted, Katherine continued her survey over the following months—still wishing that the natives would be “better behaved” (cf. this comment on a young “living Buddha” in Qinghai). Leaving the island in August 1915, she reached Liverpool in February 1916.

Back in Oxford, Larson describes the city during the war. Somerville had now become a military hospital. With most able-bodied men having joined the military, women were running the city in unprecedented numbers, in shops, schools, banks, businesses, factories, agriculture, and relief work.

After her return from Siberia, Maria Czaplicka was given a full-time position as lecturer at the University Museum. She found time to provide for the War Trade Intelligence Department, and with Poland occupied by the Russians, she lectured in support of Polish nationalism. She took gladly to farm work.

Winifred Blackman and Egypt

Another woman who took the Oxford diploma was Winifred Blackman (1872–1950). Without formal education, and already in her forties, she studied while volunteering at the Pitt Rivers Museum. Her older brother was an Egyptologist, and she too gravitated towards the region.

Only in 1920, aged 48, did she take the opportunity to visit the country, but thereafter she spent at least six months living there every year for the next twenty years. Her interests soon evolved from archaeology to ethnography. As her Arabic improved, her informant Hideyb Abd el-Shafy began introducing her to the local customs of Upper Egypt, though in 1923 he was murdered by “young roughs” in a mysterious incident.

Egypt was volatile, with anti-British feeling running high, and blood-feuds common. But Winifred found herself in demand as a healer, and she felt more valued there than in England. Again, funding was a constant concern.

It was a far cry from sewing cushions for the church bazaar or attending lectures at the museum.

With All Due Respect, even now I find it hard to imagine an uneducated 48-year-old, female or male, embarking on a career as ethnographer of a remote society.

Larson now returns to Barbara Freire-Marreco, with her marriage at Woking in 1920—part of her gradual withdrawal from academic life. In 1912, declining an offer to do fieldwork on the Navajo, already a popular topic, she had preferred to deepen her studies of the Tewa, staying for four months with the Hano people on the plateau of the High Mesa in Arizona. Their culture varied in interesting ways from that of the people of Santa Clara whom she had studied in 1910. Again she found it hard to gain their trust, and again her relationship with her informant Leslie Agoyo prompted resentment. She paid a brief return visit to Santa Clara.

With the pull of her English family ties, she now declined an offer of a post at the American School of Archaeology for the third time. Her war work then put such thoughts aside. Another job offer from the USA came in 1919, but her marriage in 1920 spelled an end to her academic career.

The sad end of Maria Czaplicka

Maria Czaplicka had followed up her research on Siberia with a book on the Turks of Central Asia (1918). But after the war, funding was no longer available for her to keep her post at Oxford; she wrote unsuccessfully to Franz Boas at Columbia in search of work there. As she sought funding to make a return trip to Siberia, she made a three-month lecture tour of the States in 1919–20. Then, after a visit home to troubled Warsaw, she took up a post as lecturer at Bristol University. Though sad to leave Oxford, she seemed “cheerful and gay”. But in 1921, learning that her fieldwork application had been rejected, she committed suicide, still only 36 years old.

The following year her fellow-student Malinowski published his seminal (sic) Argonauts of the Western Pacific.

There are poignant parallels in the lives of Czaplicka and Malinowski. Both Polish, they arrived in England in the same year to study anthropology at the LSE, and both went on to spend the war working in the field. While Czaplicka was strapping herself into a sledge in the Arctic in late 1914, Malinowski was pitching his tent on a tropical island in the Pacific. After the war, as her research gradually faded from memory, Malinowski not only became synonymous with Pacific anthropology, he put Pacific anthropology at the very heart of the discipline.

As Larson observes, Malinowski was not alone in his study of the Pacific; Gerald Wheeler, Diamond Jenness, Gunnar Landtmann, and Arthur Hocart had all done substantial work there. By this time a trend was emerging in anthropology for accounts of a single location; and ethnography was gaining ground over the mere collection of artefacts for museums.

Beatrice Blackwood and New Guinea

Beatrice Blackwood (1889–1975) had studied English at Somerville before the war, and became a student of Maria Czaplicka, whose Siberian field notes she helped organise. After the war she continued to work in Oxford, and in 1924 she spent a period doing fieldwork in the States.

In 1929, aged 40, en route for the Solomon Islands, she stopped off in Sydney to meet the lively young anthropologists who were then in town, including Margaret Mead (whom she found arrogant and patronising), Reo Fortune, and Raymond Firth—all watched over by the senior Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown.

Reaching Rabaul in New Guinea, Blackwood consulted the government anthropologist Ernest Chinnery, who guided her search for a suitably safe field-site.

First she visited the American anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker in Lesu, a village of neighbouring New Ireland. She then moved on to Chinnery’s choice of Buka in the Solomon Islands.

Blackwood felt huge pressure to succeed in Melanesia, and often doubted herself. “Did he ever darn his stockings?” she once asked in good-humoured exasperation while pondering Malinowski’s masterpiece. Needles and thread did not make it into academic monographs, and neither did feelings of depression and inadequacy, or government officials and missionaries, or the myriad ways in which anthropologists, and the people they studied, depended on the colonial infrastructure. There was no truly untouched community where an anthropologist could safely work, nor was there a completely coherent, self-contained story to be told that revealed the timeless essence of a society.

Of course, such insights would later become an essential aspect of anthropology—among much discussion, see e.g. Barz and Cooley (eds.), Shadows in the field. And since the publication of Malinowski’s diary, his own methods have been much scrutinised.

Like Routledge on Easter Island, Blackwood soon saw through the idyllic appearance of the coral islet of Petats. The Methodist mission there seemed to have effectively destroyed local traditions. After two months there, resenting Chinnery’s choice, she moved on to the village of Kurtachi on Bouganville Island. There the Catholic mission teacher seemed “harmless”, and the locals were more forthcoming.

Chinnery was acting on deep-seated fears about women working alone in New Guinea, which were largely unfounded. The indigenous population was seen as innately inferior, and the menfolk were assumed to present a sexual threat to expatriate women. But Blackwood gave short shrift to such paranoia.

She began the long journey home in October 1930. Expressing another common sentiment of the fieldworker, she wrote to Arthur Thompson in Oxford,

You will ask my lots of questions I can’t answer and I shall wish I could go back again and find out.

After publishing her book Both sides of Buka passage in 1935, Blackwood returned to New Guinea the following year. Again overruling Chinnery’s counsel, she made a base among the Anga people in the mountainous jungle of the interior. They had indeed attacked several colonists in recent years, and inter-tribal warfare was common. The site she eventually settled on was something of a compromise. On reaching the village of Manki she was disappointed by the government and missionary presence: it seemed less “primitive” than she had hoped—yet another reminder that “it’s always too late”. Blackwood’s work

would always be limited by an insurmountable and eternally frustrating problem: forbidden from living in the uncontrolled areas, beyond the reach of the government administration, she was forced to work with people whose culture had been affected by contact with colonial settlers.

Of course, such acculturation was later to be a given, even a stimulus for research.

Blackwood found it hard to gain access to the deeper levels of their cultural life. In October she wrote

Nothing especially interesting has happened during the three months that I have been here.

A kitten called Sally, a gift at the aerodrome on her way to Manki, made a useful go-between.

In December she moved to Andarora, which more closely resembled the “Stone Age culture” she was seeking. But her presence caused tensions.

Anga aggression was the only aspect of their culture that outsiders experienced. They became known as violent, without anyone properly understanding the way violence was valued in their communities or how it shaped individuals’ identities.

They never fought while she was there, perhaps out of fear of government reprisals.

Blackwood left New Guinea in August 1937, returning to New Britain to collect artefacts for Balfour in Oxford. Though her enquiring spirit was undimmed, her constant struggles to gain permission to stay in forbidden areas sapped her energy.

She reached home early in 1938. Apart from the large collection of artefacts that she had dutifully collected for the museum, she also brought back reels of 16mm cine film. Some of this silent footage is here:

and here’s Part One of a 2011 documentary by Alison Kahn:

By 1938 Blackwood was almost fifty years old. The artefacts of the Pitt Rivers Museum where she resumed her work were in ever greater need of cataloguing. Having worked there through the war, many of her seniors died over the following years; but she re-established contact with Barbara Freire-Marecco, who was still engaged with anthropological news despite her comfortable domestic life in Hampshire. Blackwood’s work was recognised; she still dreamed of returning to New Guinea. Even after retiring in 1959, having already worked at the museum for four decades, she continued to come in there until shortly before her death in 1975.

The fate of Katherine Routledge

After returning from Easter Island to considerable acclaim in 1916, Katherine Routledge and William Scoresby took some time writing up their notes for a book. With the origins of the island’s culture still enigmatic, they were keen to visit other islands in the region for further clues. In 1920 they set off again, reaching Mangareva in the Gambler Islands in 1921, where they stayed for fourteen months.

In 1924, back in London, Katherine bought a large mansion in Hyde Park Gardens with her inherited wealth. Always abrasive, she became ever more unpredictable and delusional. In 1927 she threw her husband out of the house and changed the locks. They now became locked in a squalid battle over the house, and over her mental health.

Katherine dismissed her servants, boarded up the ground-floor windows and locked herself inside. She gave lucid interviews to journalists, bemoaning the disadvantaged legal status of women. In January 1929 she was taken away to Ticehurst House Hospital in Sussex, a private mental institution for the wealthy. Though relatively comfortable, it was a prison for her. She died there of a cerebral thrombosis in 1935.

The last days of Winifred Blackman

Winifred Blackman had continued scraping funds together for her annual stays in Upper Egypt. But after her 1927 book she only published two short papers. Even when funding finally dried up she managed to keep living in Cairo until the outbreak of World War Two. In 1940–41, in her late sixties, she endured the Liverpool Blitz. With the family home destroyed, along with the collections of Egyptian artefacts that she and her brother had collected, they moved to north Wales. But in 1950, soon after losing her sister Elsie, Winifred, suffering from dementia, was taken to the Denbigh Asylum, where she died in December.

* * *

In the final chapter Larson reminds us of the culture shock these women experienced on returning to the placid life of England. While fieldwork was extremely challenging, for the men it was more of an intellectual investment in a secure future; for the women, it offered elusive hopes of liberation from the constraints of their lives in England.

To become anthropologists, they had to resist powerful social forces that pressed domesticity on them at every turn; the parents who wished they would stay at home or marry; the friends who quietly disapproved of women earning their own living; the professionals who objected to female anthropologists because, as one senior colleague put it, “there are things a woman ought not to know”.

Freire-Marecco observed that her time in Santa Clara had given her “scope to live and be a real person”—part of which had to be abandoned on her return.

All this enterprise took its toll. Their mental health suffered. Czaplicka killed herself at the age of 36; Routledge and Blackman ended their lives in mental hospitals. Czaplicka, Blackman, and Blackwood never married; the price of Freire-Marreco’s genteel English life after marriage was to abandon her career.

And their pioneering work remained uncelebrated; as the multidisciplinary ethos of the early 20th century became outmoded, they were largely overlooked by the later generation of anthropologists. [1]

In her vivid narration of the stories of these admirable women, Frances Larson has a great gift for encapsulating many of the major issues in anthropology and gender.

[1] Among much discussion of various points about fieldwork highlighted here, Nigel Barley drôlely expresses the conflict between theory and field experience; the benefits of our own flounderings in the field for interpreting the reports of others; and he outlines “veranda anthropology” under the fine heading Honi soit qui Malinowski.

On a jocular note, among my roundup of posts on The English, home and abroad is Roni Ancona‘s wry take on intrepid female explorers.

The character of Chang also features in

The character of Chang also features in

and

and