Shiban ensemble, west Fujian 1962.

I’ve already introduced important early fieldwork projects after “Liberation” under the auspices of the Music Research Institute in Beijing, led by the great Yang Yinliu. Such work continued even after the chaos caused by the Great Leap Backward.

In late 1961, soon after the publication of Yang’s major survey for Hunan (and as the Morris dancing revival continued in England!) Li Quanmin 李佺民 (1924–83), who had already taken part in the 1953 survey of folk-song in northwest Shanxi, was dispatched to the far south on a trip to Fujian province, whose vibrant folk cultures were still quite unknown to Beijing scholars. [1]

- Fujian minjian yinyue: caifang baogao 福建民间音乐采: 访报告 [Folk music of Fujian: field report] (Zhongyang yinyuexueyuan Zhongguo yinyue yanjiusuo, 1963, mimeograph, 155 pp.)

Yang Yinliu’s 1956 work in Hunan had utilised both his own team from Beijing and regional cadres, considering a broad range of genres, pervaded by ritual. But Li Quanmin arrived alone in Fujian, and travelled only in the company of the young regional music scholars Liu Chunshu 刘春曙 and Wang Yaohua 王耀华 (who went on to become leading authorities on the musics of Fujian), so this project was less ambitious. In their survey from 12th November 1961 to 28th January 1962 they conducted both overviews for particular counties and interviews on specific genres. Their fieldnotes are reproduced more or less as they were taken at the time.

Even today, outsiders’ impressions of the musical cultures of Fujian may largely be based on the glorious nanyin chamber ensembles of Hokkien communities around Quanzhou and Xiamen, but the report was the first to provide a window on the huge variety of expressive cultures throughout the province. Indeed, while the history, music, language, and ethnography of nanyin alone are a topic for several lifetimes, the 1986 survey Fujian minjian yinyue jianlun can only spare 22 of its 611 pages for the topic!

The cultures of Fujian may profitably be studied alongside those of the diaspora (notably Taiwan); while these have preserved many traditional features that were under attack on the mainland, the resilience of tradition in the PRC is remarkable.

They began by meeting representatives of official state troupes in cultural offices, noting studies by local scholars, and going on to assemble performers to make recordings. They focused on vocal and instrumental chamber ensembles; while, as everywhere, such groups mainly served life-cycle and calendrical rituals, the social contexts receive limited attention. The team got glimpses of the riches of local opera, but merely noted the researches of regional scholars—who, indeed, had been busy collecting material ever since the 1949 Liberation.

Though ritual connections are constantly apparent, the report gives only brief mentions of temple and household ritual specialists. The activities of household Daoists are only mentioned in passing; only since the 1980s have detailed monographs shown what a major feature of life they are throughout the region—indeed, this was the first region that scholars began to study once they were able to expand their studies from Taiwan to the mainland across the strait.

I’ve already noted the need to oscillate between wider generic surveys for a whole province or region (“gazing at flowers from horseback” 走马观花) and more detailed reports on one county, village, or family (see also under Local ritual).

As yet more political campaigns unfolded after the brief lull following the disasters of the Leap, this was to be among one of the last fieldwork projects until work resumed in earnest from the late 1970s.

Part One of Li Quanmin’s report contains reports from the southeast coastal region of the province. In Xiamen they visited the great nanyin expert Ji Jingmou 纪经畝 (1899–1986, or 1901–87), [2] recording him leading the Jinfeng group 金風南樂團.

Just west in Zhangzhou, after gaining brief introductions to jin’ge 錦歌 and shiba yin 十八音 (cf. the shiyin bayue 十音八樂 of Putian), they give a rather more detailed account of nanci 南詞 and the related instrumental shiquan qiang 十全腔. The occupational groups performing nanci were known as tangban 堂班, performing items like The Heavenly Officer Bestows Blessings (Tianguan cifu 天官賜福) before a painting of Heavenly Master Zhang; the genre seems to have spread from Jiangxi.

For the wider Longxi region around Zhangzhou, Liu Chunshu gave them an overview of various genres, including Songs to Wash the Gods (xifo ge 洗佛歌), presented as a superstitious genre from “the past”, sung during the first five moons by itinerant duos, one with a god image on his back; [3] dragon-boat songs in praise of Qu Yuan, noting ritual connections; and musics deriving from Chaozhou just south.

In Quanzhou they gained a further outline of nanyin (on which there was already a substantial amount of local research), as well as briefer impressions of shiyin (for a photo from my 1990 trip see here); they mention the Assault on the Citadel ritual drama (dacheng xi 打城戲) [4] and itinerant sijin ban 四錦班 bands of blind female singers. They also studied the venerable “casket winds” (longchui) shawm bands (on which more below)—I’ve now added one of Li Quanmin’s 1961 recordings to the playlist in the sidebar (#15), with commentary here.

The longchui casket, Tianhou gong temple, Quanzhou 1990. My photo.

In Quanzhou they also talked with the Buddhist monk Miaolian 妙蓮 (see below), making notes on his master the renowned Hongyi 弘一 (Li Shutong李叔同, 1880–1942), an authority on ritual music, and visiting the Kaiyuan si temple.

In Putian and Xianyou—another highly distinctive cultural sub-region—they learned of shiyin bayue 十音八樂, related to the local opera—itself a rich ancient tradition most worthy of study. Folk-song genres included shan’ge 山歌, itinerant lige 俚歌, and “singing the nine lotuses” (jiulian chang 九蓮唱). Li Quanmin reproduces a local draft for the new Putian county gazetteer, which includes a section on “ritual music” (fashi yinyue), outlining Buddhist and Daoist groups.

A clue now led them to make a detour to the poor Badu region of Ningde, north of Fuzhou, to record the two-part folk-songs of the She 畲 minority there—just one of the regions where they dwell through Fujian and adjoining provinces. Li Quanmin lent his recordings of the songs to the provincial Broadcasting Station in Fuzhou for copying—who promptly lost them.

The whole of Part Two is dedicated to the largely Hakka cultures of southwest Fujian further inland. Even their studies around this region involved lengthy journeys. Incidentally, this is yet another region where household Daoists still have impressive traditions.

Here the team focused on the shiban 十班 (in some areas known as shifan 十番) and jingban 靜班 groups. They soon discovered the complexities of local terminology. Mostly amateur groups, with a core of stringed instruments, they are often based on local drama; but usually there is also a strong link with occupational shawm bands and percussion groups.

In the Longyan region the jingban were related to Raoping chui 饒平吹 shawm bands, named after the region further south in Guangdong. Moving west from the regional seat, in Shanghang they noted the effects of historical migrations. In Liancheng they learned from Luo Xuehong, head of the county song-and-dance opera troupe, an erstwhile accompanist of Buddhist and Daoist ritual specialists and marionette bands—reminding us that state troupes were then full of such experienced “old artists”.

They continued their studies of the jingban in Changting—where they also gain a tantalizing clue to the furen jiao 夫人教 (or “singing Haiqing” 唱海青) exorcistic ritual performed by household Daoists to protect children (cf. guoguan). In north China Haiqing 海青 is a common subject of ritual shengguan wind ensemble pieces, but it has been assumed to be a bird of prey; however, material from Fujian shows that he is a deity there: Thunder Haiqing (Lei Haiqing) is a manifestation of Tiandu yuanshuai 天都元帥.

Still in Changting, they gained further material on shiban groups, visiting Dapu 大浦commune to learn of the temple fair to the Great God of the Five Valleys (Wugu dashen 五谷大神). Returning to Longyan they continued to explore the relation between the jingban and shiban groups. Hearing of the lively scene in Kanshi town in Yongding, based on its temple fairs, they moved on there. Back in Longyan again, they ended their trip with a visit to a jingban group in Dongxiao commune.

Throughout the trip, in addition to occupational performers, they met amateurs— factory and manual workers, traders, and peasants—whose livelihoods had been in flux for several decades. But alas, what we can’t expect from such sources is discussion of the changing society (though see here, and for more revealing official sources, here). Fujian was far from immune from the famine, [5] with migrants fleeing in all directions—though the report discreetly refrains some such topics. A desultory sentence on the itinerant singers of lige claims:

Before Liberation most people weren’t keen on singing it [?!], but after the Great Leap Forward in 1958 the government esteemed it and [sic] used it for propaganda.

But in contrast to propaganda, this is just the kind of folk activity that was reviving among migrants in the desperation following the disasters of the Leap.

Since the 1980s

While Li Quanmin’s survey is less impressive than Yang Yinliu’s earlier report on Hunan, it laid a groundwork for later studies of Fujian. After the interruption through the Cultural Revolution, the liberalisations of the late 1970s allowed fieldwork to resume on a large scale, largely under the auspices of the national Anthology project—for whose fruits in documenting instrumental ensembles and “religious music”, click here.

Even before the publication of the Anthology, a single-volume survey appeared by two provincial scholars who had accompanied Li Quanmin in 1961–62:

- Liu Chunshu 刘春曙 and Wang Yaohua 王耀华, Fujian minjian yinyue jianlun 福建民间音乐简论 (1986).

Its 611 pages not only give more informed accounts of the genres introduced in the 1963 survey, but provide more extensive coverage of a wider range of regional genres, including the lesser-known north of the province. The volume adopts the overall classification that had been developed from the 1950s, now enshrined in the Anthology—and as ever, most of them are strongly interconnected:

- folk-song (with a wider coverage of the She minority, pp.199–229)

- narrative-singing (nanyin appears here, alongside genres such as jin’ge, nanci, and beiguan)

- opera, including Minju, Gezai xi, Pu–Xian xi, Liyuan xi, Gaojia xi, marionettes, and shadow puppets

- instrumental music: various shifan and shiban genres, longchui, and so on.

A helpful map of the transmission of shiban.

There is no separate section for “religious music” [sic], but some “religious songs” are briefly introduced (pp.144–63), and ritual genres pervade all the categories.

On a very different note, Wang and Liu end with an introduction to the Fujian tradition of the qin zither, which had also formed part of Zha Fuxi’s national survey in 1956.

Fieldtrips, 1986 and 1990

On my first stay in China in 1986, after exploratory trips to Wutaishan, Xi’an, and Shanghai, I visited Fujian, gaining a preliminary glimpse of nanguan and learning much from Ken Dean, then based in Xiamen. Ken was among the first scholars to cross the strait from Taiwan to the mainland to study local Daoist ritual traditions, and his detailed early field reports are most inspiring (see here; cf. Daoist ritual in north Taiwan):

- “Two Taoist jiao observed in Zhangzhou”, Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 2 (1986), pp.191–209

- “Funerals in Fujian”, Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 4 (1988), pp.19–78

- “Taoism in southern Fujian: field notes, fall, 1985”, in Tsao Ben-yeh and Daniel Law (eds.), Taoist rituals and music of today (1989), pp.74–87.

Ken’s fieldwork led to major monographs:

- Taoist ritual and popular cults of southeast China (1993)

- Ritual alliances of the Putian plain (2 volumes, 2009)

and most illuminating of all, his vivid 2010 film

- Bored in heaven, on ritual activity in Putian (for differences between his approach and more text-based Daoist scholarship, see here).

With Ken I attended a nocturnal ritual in a Quanzhou temple, with marionettes (on which, note Robin Ruizendaal’s wonderful 2006 book Marionette theatre in Quanzhou—with rare coverage of the fortunes of such groups under Maoism):

Marionettes for nocturnal ritual, Quanzhou 1986. Photos in this section are all by me.

And I visited the beautiful county of Hui’an on the coast:

Hui’an 1986: left, nuns; right, the distinctively-clothed women of Hui’an.

After my first serious survey of ritual associations on the Hebei plain in 1989 with my trusty colleague Xue Yibing, he accompanied me on my return to Fujian in early 1990, moving north from fieldwork around Guangdong on a reccy for what became chapters 14 and 15 of Folk music of China. Xue Yibing’s careful notes were as precious as ever. Like Li Quanmin, we often began by visiting local experts; but we also sought out local ritual practice, such as temple fairs—and by contrast with most regions of north China, such activity was ubiquitous despite all the traumas of the intervening twenty-eight years.

In Quanzhou city we spent wonderful time with nanyin groups, and learned more about longchui, still magnificent, with the versatile ritual accompanist Wang Wenqin 王文钦 (then 66 sui) and shawm master Huang Tiancong 黃天從 (67 sui, son of Huang Qingquan who led the 1961 recording) as our guides. In Puxi village nearby we found shiyin (see photo here), and in Hui’an we visited one of many groups performing beiguan—a major genre in Taiwan.

As always, folk ritual is the engine for expressive culture, and a variety of such groups assemble for a wealth of temple fairs. In many communities around Fujian the extraordinary ritual revival was stimulated by funding from the overseas diaspora.

At the Tianhou gong 天后宮 temple in Quanzhou city we attended a vibrant Dotting the Eyes (dianyan 點眼) inauguration ritual for the goddess Mazu—with pilgrim groups from all around the surrounding area as well as Taiwan (including palanquins holding god statuettes, shiyin bands and a Gezai xi drama group), a Daoist presiding, ritual marionettes inside and outside the temple, along with magnificent nanyin and longchui.

Above: (left) ritual marionettes; (right) a Daoist officiates.

Below: longchui led by Wang Wenqin on foot-drum and Zhuang Yongchang on shawm.

Later the longchui performers invited us to a gongde funeral at which they alternated with three household Daoists performing a Bloody Bowl (xuepen 血盆) ritual, as well as a lively Western brass band. And the distinguished marionette troupe performed moving excerpts from Mulian 目連 ritual drama for us: [6]

Having recently found the sheng-tuner Qi Youzhi in a town south of Beijing thanks to Yang Yinliu’s precious 1953 clue, we now visited the Buddhist monk Miaolian, whom Li Quanmin had visited in 1961. Now 78 sui, he was still at the Kaiyuan si temple; indeed, he had even remained there throughout the Cultural Revolution, when he was among a staff of over twenty resident monks.

Miaolian with Xue Yibing, 1990.

We ended our visit in Fuzhou, gaining further clues to the chanhe 禪和 (doutang 斗堂) style of folk ritual (see Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Fujian juan, pp.2086–2243).

As for Li Quanmin previously, the trip merely allowed us to gasp at the enormity of the expressive cultures of Fujian. As I began focusing on north China, I was increasingly aware that local ritual activity must be a major topic there too.

Meanwhile the anthropologist Wang Mingming was doing detailed work on the history and ethnography of the culture of the Quanzhou region.

The Anthology

And meanwhile the monumental Anthology was being compiled, with volumes for folk-song, narrative-singing, opera, instrumental music, and dance each weighing in at between one and two thousand pages—and as usual, the published material is only a small part of that collected. To be sure, much of this consists of transcriptions (which anyway are of limited use if we can’t hear the recordings), but even the textual introductions (as well as the vocal texts, often orally transmitted) offer valuable leads.

Coverage of nanyin, the subject of a vast wealth of separate research, is distributed through the volumes on narrative-singing, instrumental music, and indeed opera. The Fujian folk-song volumes are among the most impressive in that category; the songs of the She minority are covered at some length (pp.1240–1412).

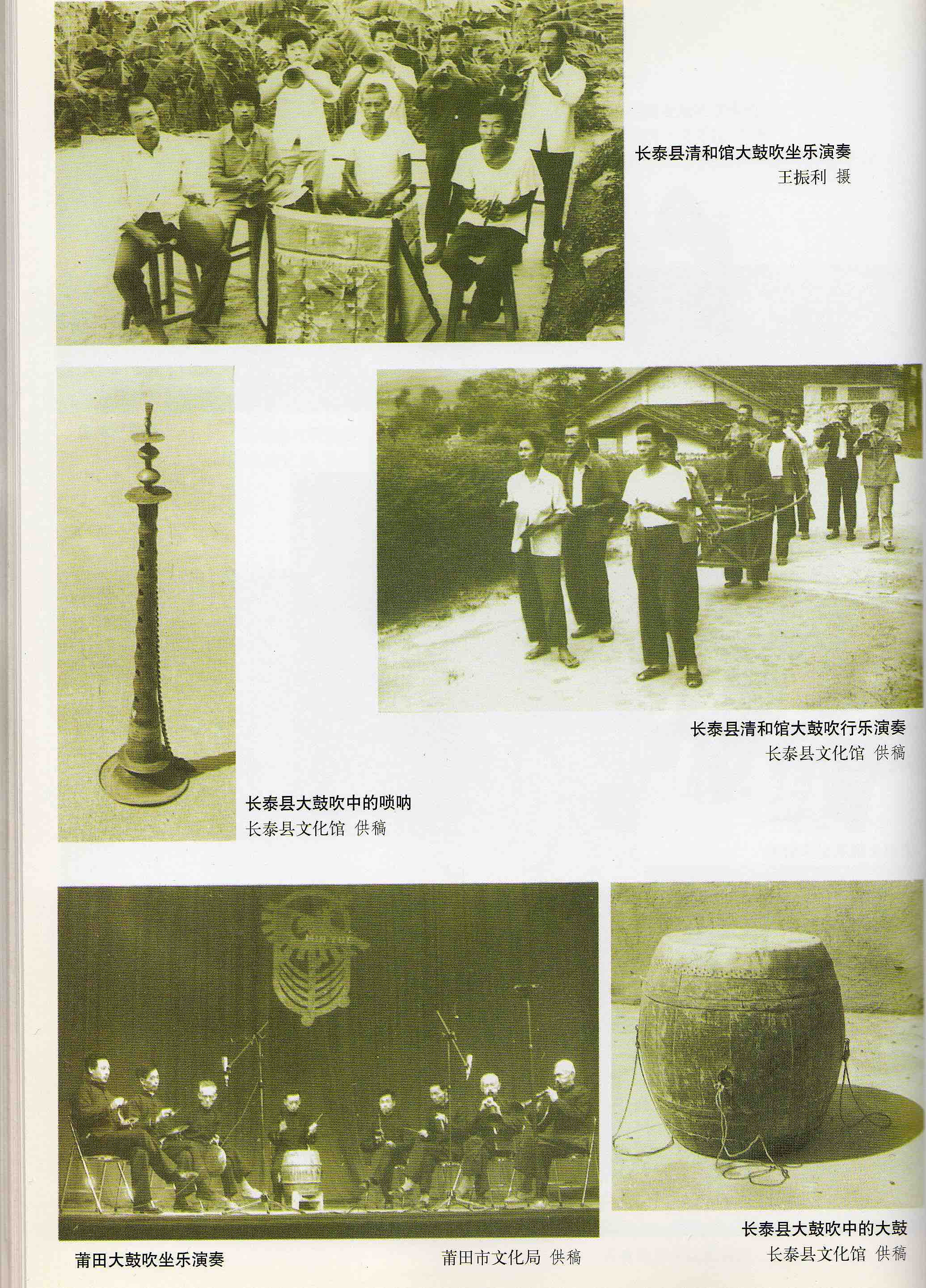

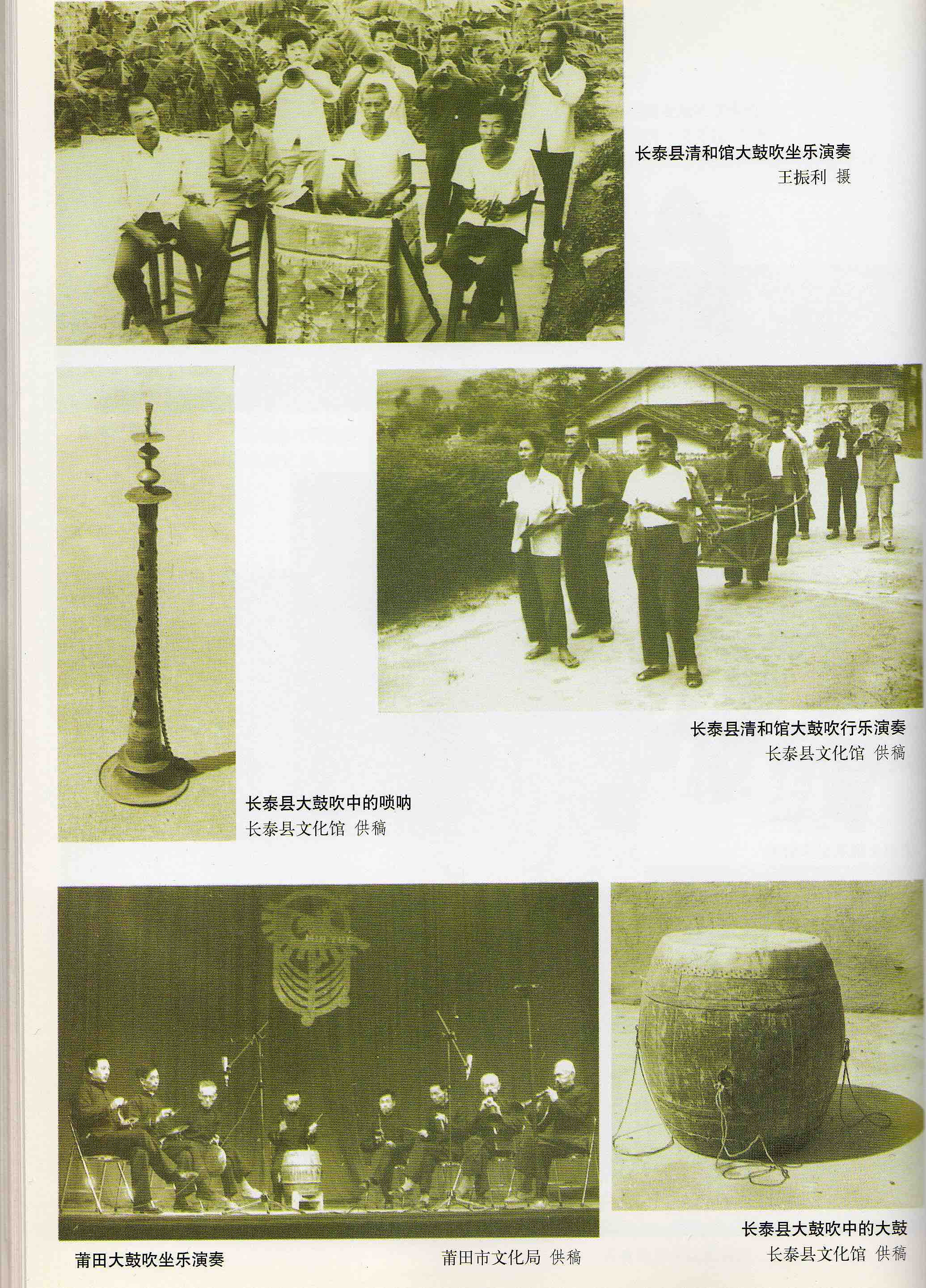

Shawm bands of Changtai county, and (lower left) of Putian county.

In the instrumental music volumes, besides the string ensembles much of the coverage yet again describes shawm and percussion bands. As ever, we find leads to genres that are still largely unknown outside their vicinity. And of course any single county has several hundred villages, all with their ritual and entertainment performance traditions. In 1986, for instance, at least 139 village nanguan societies were active in the single county of Nan’an.

Beiguan, Hui’an county.

While the coverage of “sacrificial” and “religious” musics (pp.1757–2683) has now been eclipsed by the detailed projects on household Daoists led by scholars based in Taiwan and Hong Kong, the Anthology offers some leads. After a very brief introduction, we find transcriptions of items from the rituals of household Daoists in Putian, Xianyou, and Nan’an counties (pp.1757–1836, 2448–2683). Also introduced are xianghua 香花 household Buddhists of Fuzhou and Putian (pp.2086–2423); and the She minority feature again (pp.1836–93).

For all its flaws, the Anthology is a remarkable and unprecedented achievement.

* * *

Although field research since the 1980s has taken the study of the diverse sub-cultures of Fujian to a new level, it’s important to note the energy of the years before the Cultural Revolution. Indeed, apart from the riches of its performance traditions, Fujian has long had a deep tradition of local scholarship.

Of course, in the context of the pre-Cultural Revolution period, brief visits inevitably focused on reified “genres” rather than on documenting social activity. And “hit-and-run” trips by fieldworkers from Beijing or London can never compare to the long-term immersion of local scholars, like Wu Shizhong for nanyin, or Ye Mingsheng for Daoist ritual. Ye’s account of one single ritual performed by one group of Lüshan Daoists (even while hardly addressing their lives or ritual vicissitudes since the 1940s) occupies a hefty 1,418 pages!

As always, expressive culture—based on ritual—makes an important prism on the changing social lives of local communities.

See also Religious life in 1930s’ Fujian.

[1] See my Folk music of China, ch.14, with extensive refs. up to the mid-1990s; to attempt an update would be a major task. I have fallen back on pinyin, rather than attempting to render terms in local languages.

[2] See Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Fujian juan 中国民族民间器乐曲集成,福建卷, pp.2703–4.

[3] Cf. Fujian minjian yinyue jianlun, pp.130–36.

[4] For some refs., see my Folk music of China, p.293 n.17.

[5] For the Quanzhou region, see e.g. Stephan Feuchtwang, After the event: the transmission of grievous loss in Germany, China and Taiwan (2011), ch.4.

[6] Among a wealth of research on Mulian drama, see David Johnson (ed.), Ritual opera, operatic ritual: “Mulian rescues his mother” in Chinese popular culture (1989).

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

The list of countries also evokes the Olympic medals table—with USA, China, and even the UK ranking high, pursued by France, Germany, Australia, Japan, and so on. Further down, Romania, Thailand, and Brazil put in plucky performances. I like some of the fortuitous juxtapositions that it produces daily (left).

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

To accompany my new post outlining diverse performance genres of

After

After