On modern Tibetan society, Jamyang Norbu has long been a stimulating voice (note his splendid website). Here I’ve already admired his remarks on Tibetan opera, and his article The Lhasa ripper. His novel

- The mandala of Sherlock Holmes: the missing years (alternative subtitle “the adventures of the great detective in India and Tibet), “edited by Jamyang Norbu” (1999)

is a Rattling Good Yarn, with a serious moral—like many of the best crime novels (Philip Kerr, Tony Hillerman, and so on), both gripping and educative.

Born in 1944 in Lhasa, Jamyang Norbu was sent to a Jesuit school in Darjeeling, where he relished Kipling and Conan Doyle. After an interlude with the Khampa guerrilla group “Four Rivers, Six Ranges” in Mustang to resist the Chinese invasion of Tibet (see e.g. Jamyang Norbu’s own recollections, and Tsering Shakya, The dragon in the land of snows, Chapter 6), he became a leading light in the educational and cultural scene at Dharamsala. Combining the fruits of his early education and his experience as a Tibetan in exile, he wrote The mandala of Sherlock Holmes there (the Epilogue is dated 1989) before making his base in the USA.

Only in the Preface and the Epilogue does Jamyang Norbu write in his own voice, observing the political context in which we now read the tale.

Tibet may lie crushed beneath the dead weight of Chinese tyranny, but the truth about Tibet cannot be so easily buried; and even such a strange fragment of history as this may contribute to nailing at least a few lies of the tyrants.

Still, he indulges poetic fancy by evoking the discovery of Hurree’s notes, and Holmes’s living incarnation in a monastery.

Given the wealth of later tributes to Sherlock Holmes, the Preface opens with a wry flourish:

Too many of Dr John Watson’s unpublished manuscripts (usually discovered in “a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch box” somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox and Company, at Charing Cross) have come to light in recent years, for a long-suffering reading public not to greet the discovery of yet another Sherlock Holmes story with suspicion, if not outright incredulity.

Holmes having faked his own death at the Reichenbach Falls in 1891, Conan Doyle had the sleuth explain in The adventure of the empty house (1903, set in 1894):

I travelled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhasa and spending some days with the head Lama. You may have read of the remarkable exploration of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend.

The story is narrated by Hurree Chunder Mookerjee, a Bengali scholar/spy from Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim (based on the real-life character of Sarat Chandra Das), who takes Watson’s place as Holmes’ trusted friend and confidant. As Jamyang Norbu explained, “The Sherlock Holmes stories worked because of Dr Watson. You need someone who is sweetly endearing but also slightly dim.”

With erudite footnotes (mostly in the persona of Hurree, on both Holmesiana and Tibetan studies at the time), the novel is a most accomplished pastiche, replete with vignettes—like the use of fingerprinting for identifying criminals, introduced in Bengal in 1896, before it was adopted by Scotland Yard in 1901, or the history of the Thug cult and worship of the goddess Kali.

Holmes arrives in Bombay incognito—or so he hopes—with only a Gladstone bag and a violin case:

This was, of course, suspicious in itself. No self-respecting sahib who travelled to India was without at least three streamer trunks, not to mention other sundry items of baggage like hat boxes, gun cases, bedding rolls, and a despatch box. Also, no English sahib, at least if he was pukka, played the violin. Music was the preserve of Frenchmen, Eurasians, and missionaries (though in the latter-most case the harmonium was a more favoured instrument).

Amidst the “Great Game”, Holmes’s arrival has come to the attention of the British Secret Service in India, and Hurree latches on to him. They soon learn that his life is still in danger.

I commend your energy, Strickland. But I fear that such a direct course of action would prove futile. Colonel Sebastian Moran is a most cunning and dangerous adversary. At the moment the only net we have is too frail to hold such a formidable prey.”

“But, dash it all!” cried Strickland. “The man is an honourable soldier. […] You expect me to believe that an English gentleman, a former member of Her Majesty’s Indian Army, the best heavy-game shot in India, a man with a still unrivalled bag of tigers, is a dangerous criminal. Why, I was with him just two nights ago at the Old Shikari Club. We played a rubber of whist together.”

All along their arduous journey via Bombay, Delhi, and Simla on to Lhasa, pursued by Moriarty’s well-trained, dastardly henchmen, “Sigerson” solves baffling cases. Even in Simla, “a delightful and sophisticated town”, he is not inclined to relax; as Hurree observes,

I was really at my wits’ end trying to make him enjoy himself. […] Knowing his liking for music, I thought it would not be improper to suggest a visit to the Gaiety Theatre, where at the time a comic operetta by Messrs Gilbert and Sullivan was being performed. It was only much later that I learned that his musical interests leaned towards violin concerts, symphonies, and the grand opera.

Holmes frequents the Antiquarian Bookshop run by Mr Lurgan—another character from Kim—and enlists Hurree to teach him Tibetan. Another period note:

But I will not burden my readers with any further digression into the subtleties of the Thibetan * language, for such a subject can only be of interest to a specialist. Nevertheless, for those readers who would like to know more about the Thibetan language I can recommend Thibetan for the beginner (Re 1) published by the Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, and the Grammar of colloquial Thibetan (Rs 2.4 annas), by the same publisher.

Colonel Creighton fills them in on the situation in Lhasa:

“This is a secret report I received from K.21 just a week ago. His monastery is, as you know, close to the main caravan route from Kashgar to Lhassa, and is therefore a good place to pick up news from the Thibetan capital. Evidently things are not as they should be in Lhassa. There are rumours that two senior ministers have been removed in disgrace from the cabinet, and a much respected abbot of the Drepung monastery jailed like a common criminal. K.21 feels that the Manchu Amban is behind these events, and it is probably an attempt to undermine the position of the Grand Lama and strengthen Chinese influence in Thibet. It seems that these particular ministers and the abbot wanted the young Grand Lama to be enthroned before his constitutional age. They were opposed to the Regency, which has acquired the reputation of being influenced by the Chinese representative, the Amban.”

So in late spring, once the passes are no longer snowbound, they set off, joining the Leh-Lhasa caravan near Mount Kailash.

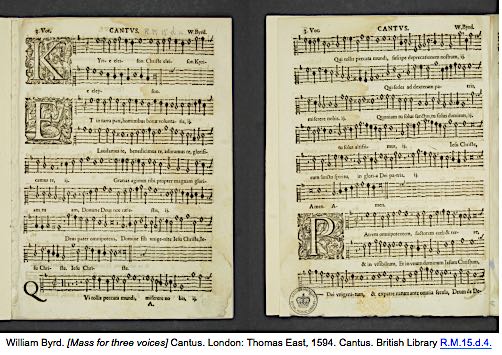

Sigerson’s passport into Tibet: da-yig arrow missive. **

Reaching the fortress of Tsaparang, Hurree tells Holmes the story of the Portuguese Jesuit community there, founded by Antonio de Andrade in 1624:

“Did the good father succeed in converting many of the natives?” asked Holmes, knocking the ash of his pipe against the side of a broken wall.

“Not very many, I would think. Thibetans are notorious in missionary circles for their obstinacy in clinging to their idols and superstitions.”

“They revel in their original sin, do they?” chuckled Mr Holmes. “Anyhow, there is a surfeit of religion in this country already. Why should the missionaries want to bring in another?”

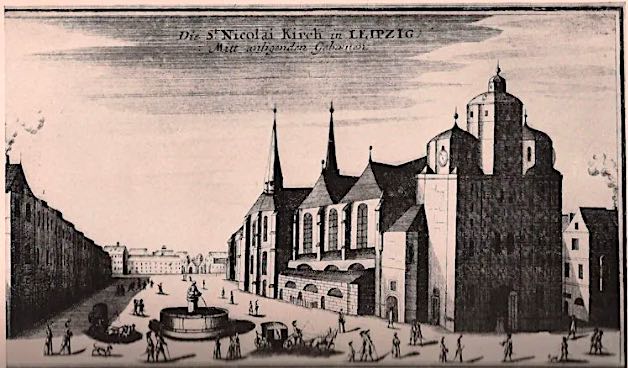

Lhasa, 1904. Source.

Eventually, with sherpas in tow (shades of The ascent of Rum Doodle?!), on 17th May 1892 they reach Lhasa. In another nice note Jamyang Norbu comments on Hurree’s text: “Only one white man, Thomas Manning, had ever set eyes on it before”:

Hurree is mistaken. John Grueber and Albert d’Orville visited Lhassa in 1661 and saw the Potala palace, although the construction was not fully completed until 1695.

For early Europeans in Tibet, see here.

As observed by Tibetscapes in this Twitter thread, the novel critiques the exoticisation of Tibet, bringing to focus Tibetan voices and perspectives. Lhasa is described not as the reified Buddhist utopia of Western imagination, but as a thriving metropolis:

Merchants from Turkestan, Bhootan, Nepaul, China, and Mongolia displayed in their stalls a ruch array of goods: tea, silk, fur, brocades, turquoise, amber, coral, wines, and dried fruits and even humble needles, thread, soap, calico, spices, and trinkets from the distant bazaars of India. Lhassa is a surprisingly cosmopolitan town, with merchants and travellers from not only the countries I have just mentioned, but also Armenians, Cashmiris, and Muscovites.

Holmes and Hurree are ushered into

a well-appointed chamber, decorated in the Thibetan fashion with religious paintings (thangka) and ritual objects, and the floor covered with rich carpets and divans. We were served tea and Huntley & Palmer’s [sic—apostrophe pedant] chocolate-cream biscuits.

Visiting the Norbulingka (“Jewel Park”) for an audience with the Dalai Lama’s Chief Secretary, they learn that Sigerson’s true identity has been revealed by the Grand Seer. As the Chief Secretary explains,

Thibet is small and peaceful country, and all that its inhabitants seek is to pass their lives in tranquillity and to practise the noble teachings of the Lord Buddha. But all around us are warlike nations, powerful and as resilient as titans. […] To the east is our greatest peril and curse, Black China—cunning, and hungry for land. Yet even in its greed it is patient and subtle. It knows that an outright military conquest of Thibet would only rouse the ire of the many Tartar tribes who are faithful to the Dalai Lama, and who are always a threat to China’s own security. Moreover, the Emperor of China is himself a Buddhist, as are all the Manchus, and he must, at least for the sake of propriety, maintain an appearance of friendly amicability with the Dalai Lama.

But what he cannot achieve directly, the Emperor attempts through intrigue…

So Holmes assumes the task of rescuing the young 13th Dalai Lama from the plots of the Chinese, in a climactic encounter with the arch-fiend himself. Finally the true numinous identity of Holmes himself is revealed. While Jamyang Norbu has long been a dispassionate critic of the Tibetan religious mindset, the dénouement indulges esoteric mysticism to the full, with the mandala of the Great Tantra of the Wheel of Time and mudra hand gestures playing a crucial role. Lhasa is free to celebrate the coronation of the young Dalai Lama.

Such intrigues can only remind the modern reader of the events leading up to the current Dalai Lama’s flight in 1959. His predecessor himself fled from the Chinese in 1910, returning from exile in 1913 (for more on the intrigues of the day, see e.g. this post by Woeser). In the Epilogue, Jamyang Norbu cites the 13th Dalai Lama’s last testament:

It may happen that here, in Tibet, religion and government will be attacked from without and within. Unless we can guard our country, it will happen that the Dalai and Panchen Lamas, the Father and the Son, and all the revered builders of the Faith, will disappear and become nameless. Monks and their monasteries will be destroyed. The rule of law will be weakened. The land and property of government officials will be seized. They themselves will be forced to serve their enemies or wander the country like beggars. All beings will be sunk in great hardship and overpowering fear; and the nights and days will drag on slowly in suffering.

Like Tintin in Tibet (1958–59, sic) and Twin Peaks, one hopes that such popular works will lead the casual reader to explore the troubled modern history of Tibet. Here’s a roundup of my posts on the topic—including Lhasa: streets with memories.

A couple of notes of my own [dated 1st April 2021] in homage:

* The aspirated initial might seem to suggest that Tibet was “discovered” by the Irish, the “h” disappearing from orthography as other Westerners heard them evoking the country. Cf. Denis Twitchett’s theory that Li Bai was an Irishman called Patrick O’Leary (n. here).

** Could it be that emissaries called out “da-yig!” to announce their arrival, a custom that eventually found its way to Venice via the Silk Road, becoming the gondolier’s cry of O-i? [No it couldn’t. Stop it.—Ed.]

In dhrupad renditions the nomtom syllables

In dhrupad renditions the nomtom syllables

Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP.

Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP.