Woman Zhang at 90 sui, 1998.

Chain-smoking cross-legged on the kang brick-bed with all the carefree abandon of the elderly, wielding her cigarettes with more relish than accuracy, Woman Zhang (Zhangshi nü 张氏女, b.1909) told us what she could about her life. As she said, entirely without feminist irony, “I had no [given] name until going to work [in 1958] in the Great Leap Forward—that’s when they gave me the name Yurong.”

Apart from the Li family Daoists (film, and book: also tag in sidebar), my other most in-depth ethnography concerns the ritual association of Gaoluo, just south of Beijing. On this blog I’ve written about two leading figures there, and the vocal liturgists, as well as their performance of “precious scrolls”—and also the village’s substantial minority of Catholics.

It may not have escaped the alert reader that much of my fieldwork is basically about the public activities of men. I made a partial attempt to redress the balance with three posts on Women of Yanggao (starting here). So here are some further notes on the status of women in rural China, setting forth from our chats with the characterful Woman Zhang in Gaoluo in 1998, and again based on vignettes from my book Plucking the winds (where you can find further detail).

Though 90 and illiterate, her mind is quite clear, and to my relief she speaks with a clear calm voice in a standard accent. Given her advanced age (she claims to remember the long pigtails still worn by men for a while after they ceased to be enforced with the fall of the Qing dynasty), our meeting should have been a fascinating glimpse into village history. But, in total contrast to the detailed day-by-day accounts of the cultured men Shan Zhihe and Shan Fuyi, I was taken aback by her ignorance of the momentous events which had convulsed the village. Of course, men can be muddled too; but this wasn’t muddle. We know a lot of men who are totally vague about dates, but at least they have participated in history, even when only trying to escape it or deplore it, and one can learn a lot. The problem was that she was not only uneducated and a woman, but had been widowed over fifty years earlier: she had simply played no part in the village’s public history. This itself was a salient lesson. We supplied the dates below: significantly, the only date she had ever heard of was 1960, the famine.

While nominally a Catholic, Woman Zhang “believes in everything”. Though she was only brought to Gaoluo from her home in a village in Dingxing just south in about 1930, she had heard stories about the famous Boxer massacre at Gaoluo in May 1900. Some of the Catholics took refuge in the Catholic stronghold of Anzhuang further south, while others fled to the Xishiku church in Beijing. Woman Zhang’s father-in-law Shan Zhong was the only survivor of his whole family from the Boxer massacre; two sons and a pregnant daughter had been slaughtered. Shan Zhong himself had gone to Dingxing town that day; on his way back he got as far as Wucun village just south of Gaoluo when he got wind of the massacre and fled, taking refuge in the Xishiku church in Beijing. After it became safe to return to Gaoluo, Shan Zhong remarried, taking a young wife.

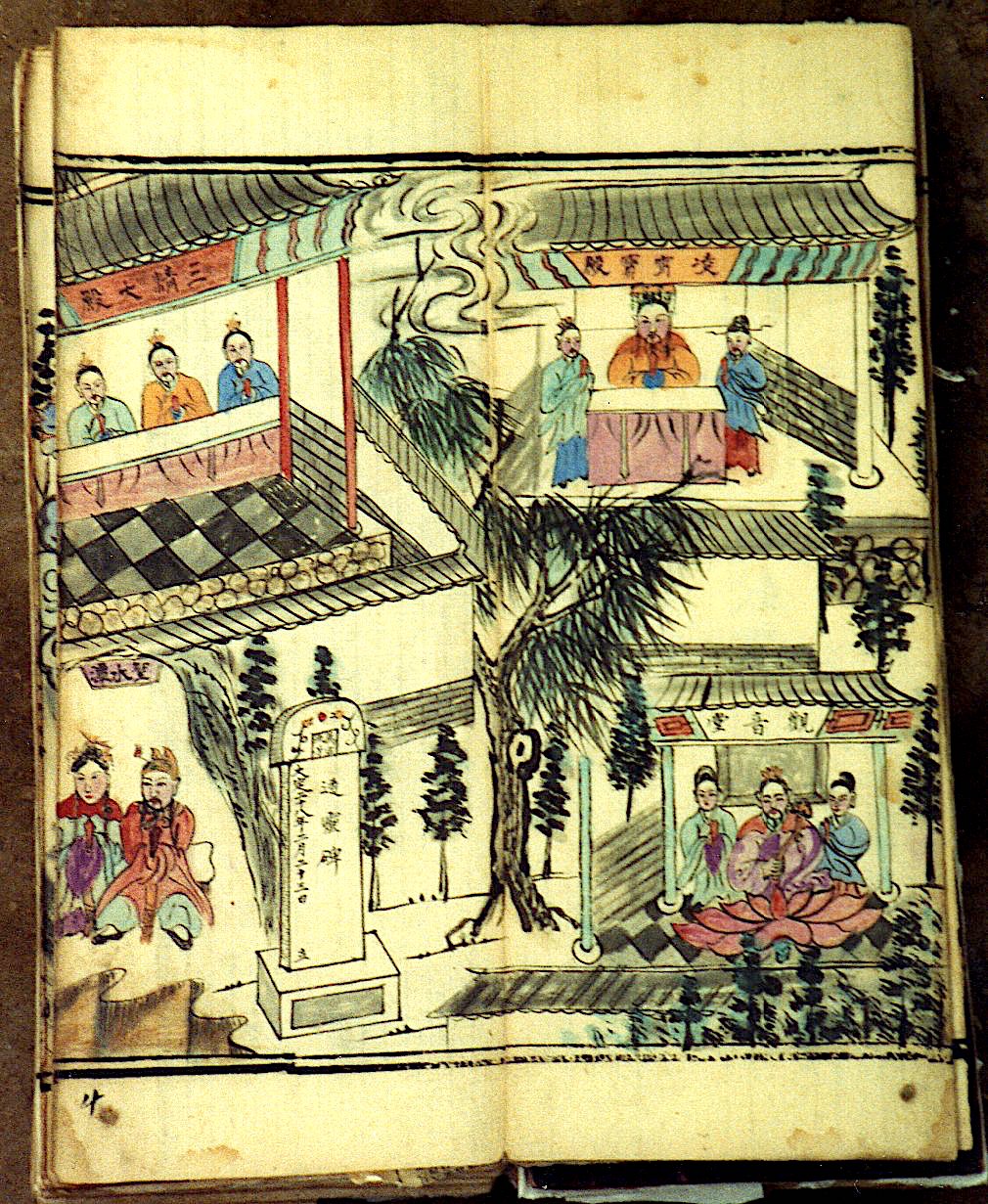

1930 donors’ list.

By 1930 the village ritual association, sensing a need to compete with the revival of Catholic power, commissioned a new set of ornamental hangings for the New Year rituals (see here, under Ritual rivalry). Shan Zhong was by now an established leader of the village Catholics—but impressively, he was one of the most generous contributors whose names (all male, as heads of households) appear on the rival association’s handsome donors’ list.

That same year Woman Zhang, then 22 sui, was brought to Gaoluo to marry Shan Zhong’s 14-sui-old son Wenli, the youngest of their three sons. Later the Italian missionaries became popular partly because like the local spirit mediums they could cure illness, and Shan Zhong also gained quite a reputation as a healer. But he died only a year after Woman Zhang’s son was born, quite soon after the building of the church.

Soon after I married here, the Catholics used to try and get me to come to church, but my mother-in-law wouldn’t let me—I couldn’t just please myself when I went out, she’d beat me. They talked it over with the other Catholic wives. They took me to church, and after the service was over they took me home, so the mother-in-law didn’t beat me.

Through the growing fug of cigarette smoke, as we tried impertinently to help Woman Zhang direct some of her ash in the general direction of the floor, she went on: “They taught me eight scriptures [jing: hymns, I think, as often in folk parlance]—I couldn’t read them, I just learnt them by heart. Dunno what the words mean, though!”

Japanese warplanes bombed Laishui county-town at 8am on 17th September (the 13th of the 8th moon) 1937, and that same day Japanese troops first entered Gaoluo. Coming from the direction of Wucun to the south, they were just passing through; they had about fifty tanks, and were covered by aircraft. The troops entered the village before Woman Zhang could take her children to the church to hide; they passed by her house. In order to dissuade them from murdering them all and setting fire to the village, the village leaders went out to welcome them. Before the Japanese even entered the village, they shot dead a villager who rashly stuck his neck out to look, but after entering Gaoluo they harmed no-one, just asking for fresh water, eggs, and meat. The venerable Shan Zhihe, along with Cai Ming (a sheng-player in the ritual association who worked as a pig-slaughterer), was responsible for looking after them and giving them water—the Japanese made them drink some first to be sure it was not poisoned. Though they soon went on their way after a token search, Japanese cavalry and infantry passed through constantly for several days on their way to Baoding, and Gaoluo villagers had to look after them.

Woman Zhang was widowed during the War against Japan. Her husband, Catholic Shan Wenli, hoping to join up with the guerrilla army, had gone out with a big stash of opium to use as a “sub” for travel expenses, but it was soon stolen. Though he eventually managed to join the army, he was wounded first in one eye and then in the body. He was brought home to die, still only in his 30s. Woman Zhang went to kowtow to Cai Yantian, who by this time had been ordained as a priest by Bishop Martina, to ask him to come and give her husband the last rites.

In our talk we fast-forwarded to 1958 and the infamous campaign for making steel—most frenetic, exhausting, and pointless campaign of the Great Leap Forward, in which many households were deprived of precious equipment, even including woks and door-latches. Woman Zhang was enlisted, and since this was virtually the first time she had been allowed out of the house, she was now given a personal name—at the age of 50 sui. She told us with an incredulous cackle: “They wanted me to make steel out of woks!” She didn’t have a clue what that was all about, and none of us could enlighten her.

1960 was the worst year: villagers agreed it was just unbearable. Though the famine is generally known as “the three years of difficulty” (sannian kunnan shiqi), it is colloquially identified simply as “1960” (liulingnian). Everyone was still expected to report for work, but only able-bodied people could survive; less sturdy villagers soon got ill and started dying. Malnutrition was as serious as at any time in the hated old society. Woman Zhang remembers having to eat yam leaves to avoid starving to death. The village cadres were in the same boat—at best, they might have been able to sneak into the canteens after work to snatch an extra mouthful of snake-melon.

She perked up when we went on to seek her opinions on the Red Guards:

Oh yeah—what were they on about? I couldn’t make it out. I know they used to parade through the streets…

But some of their victims were her fellow Catholics.

Our time with Woman Zhang was both funny and sad. She had lived through so much over the last nine decades, but had little clue what had been going on. Over the following weeks, as winter turned to spring, I often saw her sitting outside “taking the breeze” at her gateway in the bright sunshine, looking curiously at passers-by and giving me a somewhat formal nod. Life too had passed her by, which maybe was not altogether a bad thing. Pretty bad, though: she had lost her husband young, and with or without him had led a semi-existence.

Still, she reckons life is much better than in the old society, and this is no expedient courtesy to a foreign guest. Blissfully oblivious of the continuing persecution of the Catholics and the general convulsions the society was subjected to, she was genuinely grateful both for Liberation and the reforms: “Now you can get to eat barley and white flour—years could pass in the old days without that stuff.” On the other hand, when we asked her provocatively, indeed rather desperately, whether she preferred the old or the new village cadres, she had absorbed enough of the cynical climate to retort: “They’re all rubbish, they just bully people, what is there to prefer?!”

Woman Zhang perhaps typified the belief of the older generation of women. Though a Catholic since she was young, she finds Jesus rather remote: “Who of us has actually seen Jesus?” But as to “Mountain Granny” (shanli nainai, a popular term for the local goddess Houtu), “How can you help believing in her? The village women used to buy incense and go on pilgrimage to burn incense on Houshan, so I went along too. Catholics aren’t supposed to burn incense, but I went on the quiet, they didn’t know. Yes, I believe in Granny.” As we saw, she went to Catholic services, but she also enjoys visiting the association’s lantern tent at New Year, and likes both the shengguan wind music and the percussion; she remembers hearing Cai Fuxiang recite the Houtu scroll, and though she didn’t understand it, she liked to listen to that too. Cases like hers confound those “tick one box only” surveys of “religious faith” in China.

Rural sexism

Local literatteur Shan Fuyi, as ever, had a nice story. In 1990 the leaders of the association were seeking donations from villagers to refurbish their ritual building. As it happened, South Gaoluo’s nouveau-riche entrepreneur Heng Yiyou was working away from the village when they called at his house, and his wife only had a paltry couple of kuai to hand. When Shan Fuyi, who was to write the donors’ list, asked her whose name he should write, she exclaimed sharply, “Write Heng Yiyou’s name of course—do I count as a person?!”, hitting the sexist nail on the head. Shan Fuyi did as she said, but soon realized they couldn’t put Boss Heng down for such a meagre amount. When he tracked Heng down, Heng now gave a further 100 yuan, besides four long bamboo poles from which to attach the association’s pennants. Luckily the donor’s list had a blank space at the top where Shan Fuyi could write up the extra donation, giving Boss Heng appropriate recognition.

1990 donor’s list, by Shan Fuyi.

The trenchant remark of Boss Heng’s wife gives us a pretext to reflect on the status of women in village life. For the record, she’s called Li Shufen! As Shan Fuyi observes, people are not generally aware of women’s names unless they are close relatives.

In Gaoluo, although women are devout in taking part in the ritual activities which the ritual association serves, both spiritual and secular spheres continue to collude in excluding them from learning the ritual music. Their exclusion from the association reflects their exclusion from power and influence in village society as a whole, underlining the persistence of tradition and the limited scope of the revolution. Sexism, like irrational violence, is one aspect of tradition which one could understand the Communists hoping to overturn, but they were largely unsuccessful.

I must preface these comments by admitting that they are entirely impertinent: I have only added to the burdens of both women and men while in Gaoluo, feeling unable to offer any practical assistance, and never transcending my status as a guest. One of our most uncomfortable experiences in these villages is the helpless feeling of colluding in the macho tradition, all men in a group smoking and chatting while the women cook for us. At meal-times, they serve us while the men all sit around the table discussing the Important Things men talk about; the women then get to eat the cold left-overs, often outside in the courtyard, only after we vacate the table and they have served us with tea. Our entreaties for them to join us are laughed away. To be fair, this happens mainly when there are guests: normally the family eats together, though segregation is also sometimes observed.

Thinking of Shan Zhihe and his arranged marriage, or of Woman Zhang and Cai An’s mum with their bound feet, I can’t help observing that despite the continuing glaring inferiority of women’s social position today, there has been some progress—thanks to the enlightened Communist Party, as I joke with them. Young people at least choose their own partners now, and even if the women won’t share the meal they have prepared for the men, they all now have a certain amount in common, standing around making good-humoured jokes while the menfolk are chatting away over their booze and fags.

But progress has been painfully slow. After Liberation, obeying a central decree, the village Party branch dutifully elected a token female head of the new Women’s Association. Under the commune system, the vague idea was that she should implement gender equality and the female liberation campaign, but there was no specific programme, and the position was largely a sinecure. The only thing anyone could remember her organizing was International Woman’s Day on the 8th March, when the women were summoned to a meeting. After the birth-control policy began to be enforced strictly in the 1980s, that became her main duty, an onerous and invidious one, dependent largely on the orders of a male establishment.

While Party membership is the means to career progress, the Gaoluo Party branch, like most others, has made no efforts to “develop” bright young female applicants; as one cadre said, “It’s a waste of time, they’re going to leave the village sooner or later [to get married]”—exactly the reason given for denying women admission to the ritual association. Men join the Party with the prospect of becoming cadres. Women are caught in a neat Chinese Catch-22: they are not considered for Party membership because they are not going to become cadres, and because they are not going to become cadres, there’s no point in admitting them to the Party. As we saw, some girls began to attend school in the 1950s, but seldom progressed to higher grades.

Traditional morality has retained its stranglehold in many respects. There are simply no women in the village with any authority. Any woman seeking an active social role was, and is, likely to be cursed as a slut (“broken shoe”, poxie) by men and women alike. The only publicly active woman I heard of was the mother of formidable He Qing, a respected midwife. Until at least the 1960s, women were just not allowed out of the house, as Woman Zhang’s story reminded us. Women and men did not mix unless they were related. Even at the village opera in 1998, the audience consisted almost entirely of women and children; the few men who wanted to watch clambered onto the rooves or walls.

It’s clearly not that men don’t like opera. Perhaps they are embarrassed to be seen among women and children? Gender segregation is still mutually agreed upon.

Only the new karaoke bar, where separate gangs of teenage boys and girls eye each other up, posturing before the video-CD screen is overthrowing traditional morality, much to their relief and the chagrin of the elders; such bars in the nearby towns are indeed notoriously equivalent to brothels. Hence also the traditional disdain for female opera singers, who display themselves outside the house in the company of men. The female singers in the new village opera group have to watch their step—their reputation is at stake.

Returning to the association rituals, apart from women’s active participation in worship, some major female deities are worshipped, notably the Bodhisattva Guanyin and fertility goddesses like the goddess Houtu. Although the associations are invited to perform for the funerals of men and women alike, it is the eldest son who kowtows to the male leader of the male association to invite it. Donors’ lists for New Year or for special donations for new ritual manuals, god paintings or instruments list the male head of the household. In the secular sphere, government campaigns have long attempted to raise the prestige of female children in China, with wall slogans protesting feebly that “daughters are also descendants”.

Yet female infanticide remains common; under siege from the draconian birth control policy, women and men alike attend association rituals to pray to Houtu to be granted a healthy son.

The continuing exclusion of women from the ritual associations is all the more disturbing since there is a certain crisis in transmission—not so much as a result of political campaigns culminating in the Cultural Revolution, but rather since the 1980s, as young men desert the villages in search of work, at the same time espousing the modernity of pop music. Meanwhile the potentially gifted daughters of fine musicians remain in the home village, at least until marriage. Yet there is no prospect of adaptation. Girls are neither offered nor do they seek a role in public ritual.

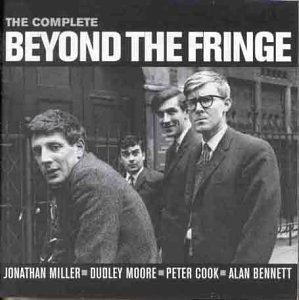

Niu Jinhua (left) with Yan Wenyu‘s widow (among several Gaoluo women with bound feet), 1996.

Since women are such a silent group in our studies, in 1996 we finally had a chat with Niu Jinhua (b.1920), mother of our host maestro Cai An—with great difficulty, I may add, since she is rather deaf; her brilliant granddaughter helped us get through, acting as interpreter. Though women are not allowed to perform the vocal liturgy or the ritual shengguan wind music, they benefit from listening to it as much as men. Asked if she likes the music, she replied enthusiastically, “Oh yes! I’ve heard it all my life, I like to listen, you can’t get tired of it (bufan).” One often hears villagers use this expression about shengguan music, but her matter-of-fact statement will remain with me, summing up its enduring impact; other women we’ve asked also express active enthusiasm. Niu Jinhua goes on, “My old home [Zhangcuitai village, just further north] has a ritual association, just the same as the one here, same pieces, they recite the Buddha too, and hang out the god paintings at New Year.” Cai An chips in: “Yes, I went there when I was young—it’s very like our association.”

As we all smile quizzically, my friend Xue Yibing then asks Cai An’s mother ingenuously,

“Were there ever any women who learnt the music?!”

“Oh no!”, she cackles.

“Why not, then?!”

“It was Old Feudalism in them days, wannit, how could women take part?!”

While I wondered if the fact that women still don’t learn meant that we are still stuck with “Old Feudalism”, her comments sparked off a group discussion (which, for men, was quite observant) on the position of women in village life.

The men, while doing nothing about it, rather like their British counterparts, readily admit that women have a much harder time than men. Their explanation of the male monopoly on ritual is feeble: “The ritual performance of the associations is a business for Buddhist and Daoist priests; what with setting up the altar and burning the petitions, everyone kowtowing, it wouldn’t be convenient if there were women there.” Though I recall that nuns used to perform rituals and even play the shengguan wind music, the point is at least that men and women should be segregated—yet even all-female performing groups are rare in rural China. But after all, women constitute the majority of those offering incense and making vows during these rituals.

The male musicians go on, just a bit more plausibly, “Anyway, women just don’t have the time to study the music; their life is much more harsh, in the old days grinding flour, making shoes, mending clothes, cooking, looking after the kids, they were so busy. Men have nothing much to do except tilling the fields; especially in winter, they have time to learn the music.”

Indeed, men (both in Gaoluo and Beijing) think women’s liberation has gone too far. A familiar male lament is heard: “Nowadays the women even get their husbands to do the household chores!” To be sure, women can have quite a temper, and men commonly deplore their fate with the nice, if sexist, pun “I’ve got tracheitis”, tracheitis (qiguanyan) being homophonous with “hen-pecked” (“wife controls strictly”). One otherwise bright young village boy, back for New Year from his studies at college in Tianjin, couldn’t see what I was on about, claiming rather wistfully that men and women in Gaoluo were entirely equal—overlooking little details like the total absence of women in positions of responsibility, their failure to go on to higher education, their relegation to eating the cold leftovers after the men have taken their fill, and the fact that several Gaoluo wives have been bought. Moreover, since able-bodied men now migrate to the towns to seek work, women are left behind on their own not only to run the house and look after the elderly and young but also to tend the fields. Apart from that, they have a great life…

Though all this doesn’t exactly get to the roots of sexism, I’ve given a couple of vignettes. That’s how things were in Chinese villages in the 1990s; so much for gender equality under Maoism or the reforms. The closest we came to influencing women’s status in Gaoluo was that Cai An’s mum finally got used to being included in a round of cigarettes—hardly a great coup in favour of the global women’s movement.

All this began to change towards the late 1990s when rural girls began to move from secondary education to college in the towns and cities—but that’s another episode in the story.