Fetching Water procession, 2011.

Much of the voluminous work on Daoist ritual focuses on recreating the glories of ancient China. While fieldwork since the 1980s has greatly enriched our understanding, the complexities of modern life rarely intrude even in descriptions of rituals observed; the search for “living fossils” dominates research, implying a timeless social cohesion of local communities.

My diachronic ethnography of the Li family Daoists in Yanggao county of north Shanxi is partly inspired by the classic studies of Geertz; and for China, Ken Dean paid attention to the tensions involved in the 1980s’ revival of ritual practice in Fujian. This post is based on Chapter 19 of my book Daoist priests of the Li family, and in my film you can observe the rituals described here.

* * *

Since my visits from 2003 the “old rules” (lao guiju 老规矩) of ritual practice have been declining rapidly. Nowadays Li Manshan’s band works for patrons, kin, and audiences who have less discrimination, and in some respects the band’s response to this lack of appreciation is to perform less scrupulously. The Daoists are deeply gloomy about the future. They love the exhilarating percussion finale of Transferring Offerings (my film, from 1.11.07) as much as I do, but “within ten years it won’t be heard any more.” They know such repertoire is precious but are helpless to protect it; they make the comment without anguish or sentimentality. Whereas Li Qing’s generation used to wear their thick black costumes underneath their red costumes even in the summer heat, now they merely wear the red costumes over their daily apparel. And for Fetching Water, Call Me Old-Fashioned, but a plastic Sprite bottle just doesn’t do the job (see Changing ritual artefacts).

Yet they still demand basic standards of themselves, maintaining many of the old rules against all the odds. They play on procession all the way out from the scripture hall to the altar, and all the way back. While singing at the altar they may sometimes seem lax (the occasional joke, even answering a mobile), but their basic solemnity shows their perceived need to maintain their reputation. Recently they tend to sing some of the hymns rather too fast in the Invitation (the Song in Praise of the Dipper, and the Mantra to the Three Generations at the gate on the return), but they still perform most of the hymns extremely slowly (notably those for Opening and Delivering the Scriptures), when surely they could go just a tad faster; nor do they abbreviate them. While singing a cappella they keep the large cymbals folded on their chests, maintaining great solemnity. There is still room for further decline.

Like his father Li Qing before him, Li Manshan worried about the stresses of being band boss and choosing suitable personnel—like band leaders in jazz, indeed. But he is far from hands-on; I would like to see this as an embodiment of Daoist wuwei “non-action.” He notes occasional blips in ensemble playing, but he rarely reprimands. The dep Guicheng tends to mime a silent beat between the slow beats on the gong, which is “not good to look at,” but Li Manshan only mildly mentions this to him when he realizes I have noticed it. Back in the scripture hall, by contrast with the way the Daoists fool around now, Li Qing and his colleagues used to “hold a meeting” about how the previous ritual had gone, always maintaining standards. Li Qing would certainly want to retain the “old rules” now, but given the hosts’ apathy he too would be helpless to do so. Even in the 1980s he presided over a radical revision of the temple fair sequence, and the Pardon ritual that he led at a 1991 funeral was very different from the manual (see Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.246–9). The decline has taken place gradually in waves over the last century or so.

When performed at all, some of the fashi public rituals have recently been radically simplified, such as Opening the Quarters, Communicating the Lanterns, and Judgment and Alms. Early one morning before a burial, Golden Noble gave me a perceptive summary of the current situation. The cycle goes from ritual (yishi) to form (xingshi) until the latter itself becomes a type of ritual; thus the ritual becomes a token, then the token becomes ossified. Let’s now discuss some instances of decline that I observed in 2011.

Ritual multi-tasking

The Li family has long prided itself on being able to split into several bands for rituals on the same day. But now the same band can even chase round more than one venue on the same day, cramming in a couple of ritual segments alternately. This is possible thanks to both improved modes of transport and the hosts’ lesser demands. Even on his own, Li Manshan can now zoom from smashing a bowl in one village to decorating a coffin in another.

One morning in 2011 while doing a burial at Houying they fitted in a half-day appearance at the new temple outside Lower Liangyuan. Li Manshan, Li Bin, and Wu Mei left at 7.30am to Open Scriptures there, hooking up with three other Daoists; then they hurried back to Houying for the burial procession before returning to Lower Liangyuan again, playing a long shengguan suite seated round a table outside. Later in a smoke-filled room to the side of the temple complex I found a large group of people, mainly women, clustering round a spirit medium who was curing illnesses. I now realized this must be the main reason why the temple was being rebuilt.

Fast food, Daoist style

In May 2011 I was roped in to take part in another perfunctory ritual.

The band is doing a funeral in Golden Noble’s village of Houying. After a fine Invitation ritual and a jovial supper, before the evening Transferring Offerings, they have agreed to cram in another quick Transferring Offerings at Wujiahe village, half an hour’s drive away along winding little roads. So we all cram cordially into Yang Ying’s car—Golden Noble stays behind to attend to the kin, so I dep for him on gongs.

This other funeral is a very minor affair, with paltry altar decorations, and no-one minds when we rush through the offerings at hectic pace—indeed, they expect us to do so. For the three sections we just sing brief excerpts from hymns, far from the long sequences prescribed. This is exceptional, actually, and the Daoists only agreed to do it because the host begged them.

I already hinted at a certain recent simplification of Transferring Offerings. As we pile back into the car back to Houying for our main course, I joke that this is like a ritual version of fast food, a drive-in take-out. Just further north, hosts are already more “careless”—there they no longer even request the Invitation. Even in our area, some patrons now request shorter hymns for Transferring Offerings; Li Bin recalls a funeral recently where the host didn’t want the ritual at all, considering it “too much hassle” (Pah!). Still, on our return to Houying they do a beautiful full sequence, with three long plaintive hymns.

A flawed funeral

During my stay in October 2011 I am looking forward to a three-day funeral in a nearby village; such funerals are no longer common, so I should be able to attend several rare rituals. When the day comes I am in high spirits; it is a beautiful sunny autumn morning, and it is a picturesque little village with a population of only two or three hundred.

Over the next couple of days my hopes are progressively deflated. First I discover that the Daoists now commonly simplify the three-day sequence. But in this village, as they realize the depth of their hosts’ ritual ignorance, they are even more casual. I begin to realize that a crucial factor in the maintenance of ritual is whether or not “the host is cooperative” (dongjia peihe 东家配合). The Daoists are used to having to guide the host family, but here they sense reluctance.

The deceased woman was 93 sui. Her third son had died seven years ago, aged 52 sui; his coffin was removed from the grave for the purpose of burying them jointly, and it now stands at the roadside under an awning. Li Manshan did the initial determining the date, decorating the new coffin on the third day, and Li Bin decorated the soul hall two days before the funeral. So they may have sensed a certain ignorance in the host family long before they turned up to do the rituals—but work is work.

The scripture hall—as usual at the other end of the village to allow for a suitably lengthy procession—is the house of an affable but poor 50-sui-old bachelor. It is still hot, and his house is full of flies. I gaze admiringly at the wall paintings around the kang brick-bed of our host; their dilapidated charm reminds me of Ming dynasty murals, and I am taken aback to learn that they were painted when the house was built in 1978!

After the first two morning visits to Deliver the Scriptures, Wu Mei nips into town on his motorbike to collect his new bank card while the others return to Pansi for the burial procession there (more multi-tasking). I give this a miss, chatting with our host as he busies himself sorting the corn harvest piled up in his courtyard. The Daoists return from the Pansi burial at 11.25am, so there is only time for three of the usual four Delivering the Scriptures this morning. The Opening the Quarters ritual, once prescribed at this stage of a three-day funeral, is no longer performed in Yanggao.

Lunch is followed by a siesta. With Li Manshan still busy writing ritual documents on the kang, there is only space for three of us to rest there; two more Daoists recline in Yang Ying’s car, while Wang Ding nods off perched precariously on a narrow trunk. Then a couple of Li Manshan’s mates from Houguantun turn up to chat with him.

At 3pm the Daoists set off on procession to the soul hall for the afternoon Opening Scriptures. This turns into another Failed Experiment, and this time it’s all my fault. At my request they sing Eternal Homage (see here, under 3rd moon 4th), a very slow hymn that I have never recorded. Only afterwards does it transpire that it is commonly accompanied by shengguan; this is the first time they have tried the a cappella version for over twenty years. On the gong Wang Ding, then still inexperienced, keeps going too fast, and it’s a mess. Back at the scripture hall they rehearse it diligently. At least this shows that the a cappella version can still be performed.

Then the Fetching Water ritual (my film, from 41.06). First to the soul hall to collect the kin, then to the rather distant “river,” and back to the soul hall, ending with a fine sequence of popular errentai melodies and clowning. Again, for this sequence the family is either unaware of the tradition of throwing extra money onto the table or too stingy, and I fail to persuade the Daoists to let me give them some.

After supper we admire the bright stars and rest a while in the scripture hall, watching TV, while Li Manshan writes yet more paper documents for tomorrow’s Hoisting the Pennant. When our bachelor host returns I ask him, “You been watching the opera?” He replies wistfully, “Yeah—watching the women.”

At 8.30pm to the soul hall for the long-awaited Communicating the Lanterns—so-called. Instead of the prescribed ritual, the Daoists merely light ten candles in a row on the altar table, sing the long a cappella hymn Mantra of the Wailing Ghosts, then play a quick shengguan sequence, and it’s all over! But the family is oblivious. The Daoists don’t give me any heads-up for this, nor—gratifyingly?!—does it occur to them to perform the proper ritual specially for my benefit. I now begin to realize they are disgruntled because the kin are not “accommodating” and have no understanding of the “rules.” But irrespective of relations with the host, this simplified version of Communicating the Lanterns has become standard in recent years.

So we finish early, before 10pm. The Daoists all live nearby, so we decide against enduring the modest hospitality of our bachelor host; the others zoom off on their motor-bikes while Li Bin drives Li Manshan and me back home to Upper Liangyuan.

Next morning Yuan Xuedong is depping for his cousin Yuan Gaoshan, and Yang Ying for Li Bin, who has gone off to lead another band for a funeral at Lower Liangyuan. In the scripture hall Li Manshan makes the little triangular paper flag to go at the top of the central pole for Hoisting the Pennant (my film, from 44.22), and prepares the goodies, wrapping them up carefully in the beautiful long pennant. After the first two sessions Delivering the Scriptures the Daoists prepare the arena, hanging up the paper squares, sticking the red “god place” inscriptions onto the poles, and raising the flag and pennant high on the central pole. The ritual itself they perform in full, with all the hymns at each of the poles, the kin following them around the arena and kowtowing and burning paper on cue. But for the final chase Golden Noble doesn’t bother to don the five-buddhas hat or wield the precious sword. They are going through the motions. Still, this was the first Hoisting the Pennant here for at least thirteen years. While filming I got hit twice by firecrackers, with magnificent symmetry first on my left shoulder and then not long afterwards on my right. No damage done—occupational hazard.

The Daoists then lead the kin back to the soul hall, where they sing a short a cappella version of the brief pseudo-Sanskrit coda that concludes hymns like Diverse and Nameless. Next, on a brief kitchen visit to Invite Offerings they sing the six-line hymn Songjing gongde. Returning to the scripture hall they do a brief “scriptures for well-being” session for our poor host, playing The Five Offerings on shengguan while he kneels and burns paper before the image of the City God of This Earth. Then back to the soul hall again for a perfunctory Presenting the Offerings ritual. Both Inviting and Presenting Offerings were formerly more lengthy, particularly for temple fairs. After lunch the others take a siesta, but Li Manshan has to keep writing away.

For the first Delivering the Scriptures of the afternoon they sing a cappella the long Mantra of the Skeleton. They give me permission to sit out the second Delivering the Scriptures—and sure enough, on their return they tease me that they sang Fanhun xiang, which I’ve never recorded!

Between (and occasionally even during) rituals the Daoists check their mobiles. To wonder if their Ming-dynasty forebears would have behaved like this is as pointless as the debate whether Mozart would have written jingles for TV ads; the kind of conditions that produce mobile phones are related to those that prompt people to check them during rituals.

Towards dusk they do the Invitation at the edge of the village. Li Qing’s prescription for a three-day funeral places the Invitation on the first day and Redeeming the Treasuries on the second day; but since they no longer do the Pardon or Crossing the Bridges on the second day, there is time to do the Invitation and Redeeming the Treasuries in sequence then.

After returning to the soul hall we immediately set off to the public arena for Judgment and Alms. Again, this ritual is now rarely performed, so this should be a rare chance for me. The paper squares hung up around the arena for Hoisting the Pennant are taken down and burned, then the red god inscriptions on the poles, and finally the central pole is pushed over. But again the ritual is a far cry from what it should be. As Wu Mei later confides, “It was a modernized Judgment and Alms!”

Then immediately back to the soul hall to fetch the treasuries for the Redeeming the Treasuries procession. After supper we enjoy the skit outside the gate, laughing along with the village audience, tearing ourselves away to take our places around the altar table for the first installment of Transferring Offerings. As soon as Wu Mei plays the plaintive preludial two notes of Diverse and Nameless, the tone is set for a deeply mournful long slow hymn; at once we are all deep in the groove, our concentration total. But the ritual is rather perfunctory, and Yang Ying drives us back to Upper Liangyuan by 11pm. Tired as we are, Li Manshan is keen to give me a session on how the Judgment and Alms should really go, our chat itself serving as a kind of exorcism.

On the final day, in bright sunshine, we return to the village for the burial. A list of gifts is pasted up at the gate, on red paper: gifts range from 800 down to 100 yuan, with most donors giving 200. Popular opinion is that these amounts are too mean. The preparations for the burial take ages, the kin faffing around endlessly, while Li Manshan mutters expletives under his breath. The burial procession is uneventful. The son’s coffin is to be reburied next to that of his mother. Li Manshan returns to the soul hall to stick up talismans in a brief exorcism. A protracted lunch—a wearisome day altogether. By now Li Manshan and Li Bin are really annoyed with the family. First Li Manshan has to haggle with them over the bill (never normally an issue), then Li Bin, whose gig at Lower Liangyuan ended at 3am last night, arrives to lend his support. While I wait discreetly in Li Bin’s car, a toothless ancient geezer talks at me non-stop and incomprehensibly for twenty minutes. Since I gather he was talking about the funeral, this might have been interesting, but I can only deduce the gist—that it was a crap funeral, and the family was stingy.

Then an impressively ugly peasant woman in a flimsy minidress walks by, grazing two donkeys. I seem to have stumbled onto a Fellini filmset. She takes pity on my verbal bombardment from the ancient codger, and after he wanders off she chats with me for a while in mercifully standard Chinese. She comes from Sichuan, and was sold to a man in this village twenty years ago; she recalls that it took her a couple of years to adapt to Yanggao dialect.

While Li Bin haggles with the family, quarrels and recriminations break out within the family, people red-faced from booze wandering around shouting at each other. It’s just like Christmas in England. After Li Bin drives us back home to Upper Liangyuan, Li Manshan and I recover, consulting the manuals again, clearing up a few more of my incessant queries, joking.

Cohesion and dislocation

In a modest contribution to the fine tradition of learning from failed rituals, let’s reflect on these notes.

The idea of a failed ritual tacitly accepts that the aim of the proceedings is to confirm and celebrate community solidarity—and indeed that there is such a thing. That Geertz and others don’t always find this may reflect on a supposed loss of such harmony under complex post-colonial (or whatever) social tensions; perhaps by contrast with an imagined earlier ideal age, a notion that we may obviously challenge too.

Funerals in China do indeed seem to me to represent something valuable, for both kin and community. But the family is subject to scrutiny; the event is an opportunity to confirm status within the family and community, but also a moment when underlying animosities may be entrenched. And this applies to other rituals too, like the vast territorial processions of southeast China. The conditions of the 20th century have doubtless created many dislocations in thinking; and we should recognize conflicts in imperial China, between classes and lineages, different aspirations, and so on—the very area that Lagerwey (China: a religious state, pp.153–170) seems to characterize as a kind of rural paradise is one where feuds between lineages, and between villages, have long been brutal.

Shi Shengbao with Li Manshan, Yangguantun 2018. Photo: Li Bin.

With his long experience of serving the villages in the area, Li Manshan has a network of guanxi contacts among senior men familiar with ritual proprieties—for instance, he is always happy to work in Pansi and Yangguantun, where the people are friendly and knowledgeable. At a fine funeral in Yangguantun in 2016, the gujiang shawm band was playing “greater opera” on their truck outside the gate, but stopped when we approached, as the “old rules” demand. The fine director Shi Shengbao, then a youthful 69 sui, took the job up in 1981 because he liked it. The family, and our scripture hall hosts, are cultured and respectful. Still, when you look closely, the village is still poor, with decrepit derelict boarded-up old houses. These villages are dying.

The main reason why the funeral described above was so unsatisfactory was because the Li band hadn’t performed there before, and none of the kin—or indeed the village’s ritual director or the plentiful men in their 50s to 70s—seemed to know the most basic “rules,” so Li Manshan had to explain even fundamental proprieties like kowtowing.

While the Daoists were disturbed by the whole ritual ignorance of the village, they and their rituals were not a crucial element in the failure of the event. It was through their irritation that I became aware of the conflicts within the village and the funeral family, which were going to come to a head anyway. The Daoists have routinely been simplifying the three-day sequence even for more discriminating clients; the titles of many ritual segments endure, but their content is diluted and homogenized.

Daoists still have to be invited, almost routinely; but by now they are used to not being appreciated. Since the 1990s no-one pays much attention when they arrive at the soul hall; only the kin reluctantly abandon their places watching the pop music outside the gate to go and kneel before the soul hall. It shows that a subtle degree of respect for the “rules,” from some quarter, is still expected. Sure, it is a small village, so they don’t get to put on so many funerals, but still, if they had so little clue about the proper procedures, and balked at the expense, then why did they bother requesting a three-day funeral in the first place—why not just book the Daoists for a minimal sequence? Li Manshan’s group is perfectly accustomed to doing this, and one might suppose that their irritation derived mainly from the final squabble over money. But the Daoists were already feeling disgruntled soon after arriving, long before the bill had to be settled.

The decision to hold a funeral over three days rather than two involves far more than merely the minor expense of asking the Daoists to perform a few more rituals. The pop band and the shawm band, as well as the cooks, have to be hired; the returning kin have to take extra time off their work in distant towns.

In sum, a lot depends on whether the host is “cooperative” or not. On tour in Germany in 2013 we observe that our hosts are all very cooperative—whereas we joke that Milan, scene of our most desultory European gig, should twin up with the village described above. Of course, what they expect of their hosts for domestic and foreign contexts are totally different. Abroad, the host merely has to find a good venue and provide decent hospitability; back home, the host family is expected to work closely with the Daoists in accordance with complex ritual organization.

In the Coda of my book, “Things ain’t what they used to be”, I round up the theme of ritual decline.

Note the recent diaries of Li Manshan and Li Bin. Funerals feature throughout my posts under Local ritual; see also e.g. Funerals in Hebei.

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).

Thomas Hart Benton, The sources of Country music (1975).

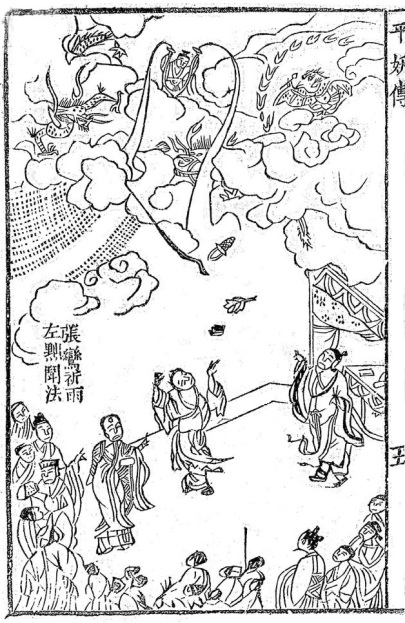

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图

《 映旭斋增订北宋三遂平妖全传》 第十七回插图