“The Bill Evans of jazz”—Robert Offergeld

The Miles Davis album Kind of blue (1959) is so iconic that every note has come to seem sacrosanct. But we need to remind ourselves that jazz is improvised; now that covers a lot of ground (as the ever-perceptive Bruno Nettl explains), but no two performances will sound the same—as when Bach and Mozart played, and as with almost any folk music you care to mention. More still than Messiaen’s Messe de la Pentecôte, or Gershwin’s Rhapsody in blue, fossilised by the exigencies of Western Art Music, jazz recordings are merely a snapshot capturing one moment in the life of an ever-changing organism.

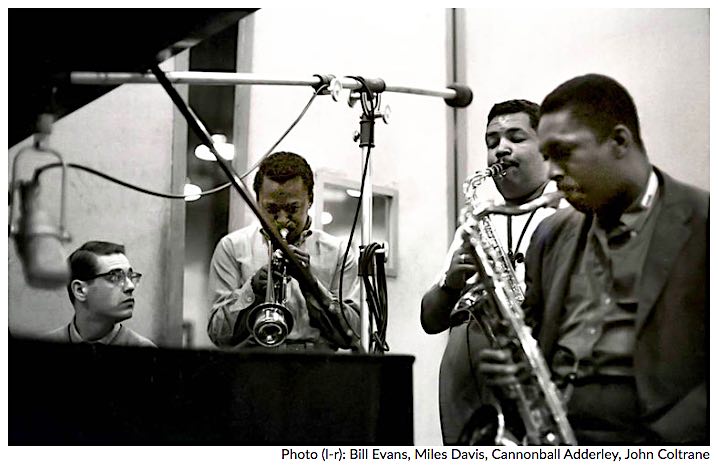

The sessions for Kind of blue were almost entirely unrehearsed—Evans opens his liner notes with a tribute to the spontaneity of Japanese painting. * I featured Blue in green, the album’s most meditative track, in my page on Ravel, whose harmonies it very much evokes—how I wish Ravel could have heard it! Its material seems to belong more to Bill Evans than to Miles (who claimed the royalties). Still, Miles appreciated him immensely:

Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on piano. The way he approached it, the sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall. I had to change the way the band sounded again for Bill’s style by playing different tunes, softer ones at first.

Anyway, to return to improvisation, we can gently rattle the cage we’ve entered of our own accord by tuning in to other versions of Blue in green, like the three 1960 takes featuring Evans’s “first” trio with Scott LaFaro on bass and Paul Motian on drums—starting with this:

Indeed, even before Kind of blue, a resemblance can be heard in Evans’ recording of Alone together with Chet Baker:

On this collaboration, Michael Quinn wrote:

While both were peerless masters of their instruments and shared a rich, evocatively lyrical playing style that bordered beguilingly on the introspective, Baker and Evans were polar opposites when it came to the discipline of performance.

Though both were heroin addicts, the musically-trained Evans never let it interfere with his meticulously precise flights of invention while the self-taught Baker became increasingly erratic and inconsistent.

* * *

You can’t have enough Bill Evans… As we bask in the archive on YouTube, it’s worth consulting Ted Gioia’s informed selection. Here’s Peace piece, 1958:

After his brief but formative time with Miles, he went on to form his “first” trio—here they are live at Birdland NYC in 1960:

And Gloria’s step, live at the Village Vanguard in 1961:

Grieving at the early death of Scott LaFaro, Evans formed a trio with Chuck Israels on bass and Larry Bunker on drums. Here’s their 1965 London appearance on Jazz 625 (ending with Waltz for Debby, cf. the a cappella version here):

Nardis also features in my post on the eponymous Istanbul jazz club—in this 1970 gig Evans plays it with Eddie Gómez on bass and Marty Morell on drums:

In 1966 he played a moving extended solo in memory of his father:

His solo album Alone again (1975):

His 1977 album Together again with Tony Bennett includes You must believe in spring! Do also listen to his versions of My favorite things and Night and day.

As one might surmise, not least from the physical similarity of their styles at the keyboard, Bill Evans seems to have been Glenn Gould’s favourite jazz pianist. Glenn O’Brien reports,

Glenn Gould said of Evans, “He’s the Scriabin of jazz”, to which the classical music critic Robert Offergeld said, “More to the point, Bill Evans was the Bill Evans of jazz. He could produce a broader tonal color in 32 measures than Glenn in his whole career.”

Discuss…

The intense meditation of his style is still evident in Reflections in D, live in Montreux, 1978:

See also Middle-period Miles, The spiritual path of John Coltrane (whom Evans, as well as Yusuf Lateef, turned on to the wisdom of Krishnamurti), Lives in jazz, and many posts in my jazz roundup.

* In interview Evans commented:

I was interested in Zen long before the big boom. I found out about it just after I got out of the army in 1954. A friend of mine had met Aldous Huxley while crossing from England, and Huxley told him that Zen was worth investigating. I’d been looking into philosophy generally so I decided to see what Zen had to say. But literature on it was almost impossible to find. Finally, I was able to locate some material at the Philosophical library in Manhattan. Now you can get the stuff in any drugstore.

But, like a Zen monk, he didn’t make a meal of it:

Actually, I’m not interested in Zen that much, as a philosophy, nor in joining any movements. I don’t pretend to understand it. I just find it comforting. And very similar to jazz. Like jazz, you can’t explain it to anyone without losing the experience.

For more on the Zen boom, see e.g. The magic of the Zen bookshop, Zen and haiku: R.H. Blyth, The great Gary Snyder, More East-West gurus, J.D. Salinger, and even The Celibidache mystique; cf. Daoism and standup.