Infatuated as I am with Mahler (series here), my posts on his symphonies inevitably include performances by Leonard Bernstein (see under The art of conducting). So I just had to watch Maestro (Bradley Cooper, 2023: in cinemas and on Netflix).

Movies about musicians are notoriously prone to faux pas (for some TV clichés, see e.g. Philharmonia, and Endeavour). Bernstein’s passion as a communicator brought an unprecedented popularity to WAM that it could never again achieve; Maestro is admirable for bringing him (if not his musical genius) to a wide modern audience.

Norman Lebrecht shrewdly observes Bernstein’s place in the roster of Great Conductors (The maestro myth pp.180–87, 192–5, and, confounding the myth that he rescued Mahler’s music from obscurity in Vienna, 198–205). Heart on sleeve, OTT, Lenny was an archetype for his era—by contrast with the austere Maestros of Yore, or indeed the benign, banal middle-managers and Early Music semi-conductors of later years.

As to Maestro, Alex Ross comments in the New Yorker:

Because Bernstein’s career unfolds in the background of his marriage, the film is relieved of the dreary trudge of the conventional bio-pic, which checks off famous moments, positions them against historical landmarks (the Cold War, the Beatles, the Kennedy assassinations). […]

By and large, Maestro benefits from what it leaves out. Some viewers have complained that such major achievements as On the Town, West Side Story, and the Young People’s Concerts are mentioned only in passing. But Bernstein’s life was so stuffed with incident that nodding to each one would have drained the movie of momentum. One omission, though, left me perplexed: the studious avoidance of Bernstein’s radical-tending politics.

The roles of Lenny (Bradley Cooper himself) and his wife Felicia (Carey Mulligan) are brilliantly played, with all the tortuous public/private psychologies of their relationship. But indeed, the film omits their considerable social activism through a period of change; Cooper had intended to include the notorious “radical chic” 1970 party, but (as he explains in this podcast) he found it would have detracted from his main theme. So the screenplay invariably chooses the personal over the political. And I agree with other reviews that lament the wider avoidance of social history (e.g. another New Yorker article; myscena.org; The critic)—a tasteful script wouldn’t have to make such scenes into a “dreary trudge” at all.

* * *

Moreover, as a Guardian review comments,

What there is very little of is music. We barely see him conduct, we hear only snatches of his own compositions, and there are frustratingly few glimpses of his passion for communicating—through performance and education—the wonders and riches of classical music.

Bernstein’s own music does play a considerable role, without quite engaging us. But the most regrettable casualty is Mahler. Despite a scene that I’ll discuss below, the movie never broaches Lenny’s deep passion for his fellow conductor-composer—he must have seen himself as a reincarnation. In Lebrecht’s words (The maestro myth, p.185; cf. Why Mahler?, pp.239–41 and passim), Mahler was

a visionary who fought against humanity’s rush to self-destruction. “Ours is a century of death and Mahler is its musical prophet” [see e.g. my fanciful programme for the 10th symphony], he proclaimed, seeking to find himself a similar role.

Apart from the moving evidence of his performances, Lenny missed no opportunity to promote Mahler’s vision, and irrespective of the movie, it’s well worth returning to his extraordinary lectures on the topic. * Without hijacking the film’s main theme, one longs for a mention of Mahler’s name, or an image—although I quite see the risks of composing a line like “Oh Felicia, what would I do without you and Mahler?”!

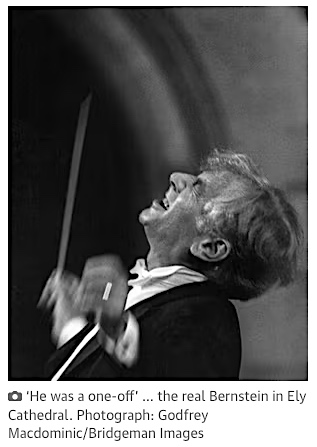

We get to hear some of the Adagietto, though it’s such a staple of movie soundtracks that for many viewers it may sound merely like generic film music rather than the work of Lenny’s alter ego. Then the long scene of the monumental ending of the 2nd symphony at Ely Cathedral in 1973 is the perfect choice, and it should be overwhelming. But if the uninitiated don’t know what it represents (for Lenny and, well, for Western civilisation!), then again one might just think it’s some random piece of dramatic romantic music; or if you love Mahler as deeply as Lenny did, then you’ll be shocked at how the lack of context largely deprives it of impact—the scene’s main point seems to be his reunion with Felicia in a make-up kiss as he comes off stage.

We get to hear some of the Adagietto, though it’s such a staple of movie soundtracks that for many viewers it may sound merely like generic film music rather than the work of Lenny’s alter ego. Then the long scene of the monumental ending of the 2nd symphony at Ely Cathedral in 1973 is the perfect choice, and it should be overwhelming. But if the uninitiated don’t know what it represents (for Lenny and, well, for Western civilisation!), then again one might just think it’s some random piece of dramatic romantic music; or if you love Mahler as deeply as Lenny did, then you’ll be shocked at how the lack of context largely deprives it of impact—the scene’s main point seems to be his reunion with Felicia in a make-up kiss as he comes off stage.

Cooper, having learned assiduously to impersonate Lenny’s conducting for the Ely Cathedral scene under the guidance of Yannick Nézet-Séguin, looks admirably impressive on the podium—but it’s also a salient lesson in how impossible it is to mimic the art of an experienced conductor. The Guardian review cited above has details of how the scene was filmed, with comments from members of the LSO:

Every detail of the 1973 performance was painstakingly reproduced, from where each player sat (“more squashed than we generally are today!”), to the mocked-up programmes, even though these were never in shot.

Players who wore glasses were asked to provide prescriptions so they could be given new ones in old-style frames—and they were all asked to let their hair grow. “Most of the guys had been asked to grow beards,” says Duckworth, “and those with very short hair had been asked not to cut it.”

And (WTAF) despite going to such lengths to achieve historical authenticity, the film used the players of today’s LSO, 45% of whom are women—whereas the 1973 LSO had only two women (the harpists) among 102 players. Is this, finally, PC gone mad?!

Despite these cavils, I admire the way Bradley Cooper has brought Bernstein’s personality to a wider audience. Perhaps it’s too much to hope that Maestro might also turn on a new generation to Mahler.

* After his 1960 talk at the televised Young People’s Concerts (wiki; complete list on YouTube here—weekly audiences for his broadcasts estimated at ten million!), more illuminating is “The unanswered question” in his 1973 lectures at Harvard:

Late in “The 20th century crisis”, from 1.37.58:

And a 1985 essay:

DO go back to Humphrey Burton’s wonderful films of Bernstein’s performances of the symphonies… Burton also filmed him rehearsing—and commenting on—the 5th, the 9th (“Four ways to say Farewell”), and Das Lied von Der Erde with the Vienna Phil (1971–72):