Thoughtful analysis of the legacy of empire is part of a productive academic trend—one which is being vehemently resisted in the corridors of entrenched power, fulminating against the “Guardian-reading, tofu-eating wokerati” (links e.g. here; cf. Fatima Manji, Hidden heritage, and sources there).

- Sathnam Sanghera, Empireland: how imperialism has shaped modern Britain (2021)

makes an engaging, accessible summary of research (among reviews, Guardian; LSE; and on the sequel Empireworld, LRB).

In the opening chapter Sanghera imagines a revival of Empire Day that would be more educational. As he notes,

It’s all very well highlighting empire awareness by talking about how our honours list still hands out Orders of the British Empire, how many of our common garden plants were originally imported into Britain by imperialists, or how Worcestershire sauce might originally have been an Indian recipe, reportedly brought back to Britain by an ex-governor of Bengal. But our imperial past has had a much more profound effect on modern Britain.

Empire explains why we have a diaspora of millions of Britons spread around the world. Empire explains the global pretensions of our Foreign and Defence secretaries. Empire explains the feeling that we are exceptional and can go it alone when it comes to dealing with everything from Brexit to dealing with global pandemics. Empire helped to establish the position of the City of London as one of the world’s major financial centres, and also ensures that the interests of finance trump the interests of so many other groups in the 21st century. Empire explains how some of our richest families and institutions became wealthy. Empire explains our particular brand of racism, it explains our distrust of cleverness, our propensity for jingoism. Let’s face it, imperialism is not something that can be erased with a few statues being torn down or a few institutions facing up to their dark pasts or a few accomplished individuals declining an OBE; it exists as a legacy in my very being and, more widely, explains nothing less than who we are as a nation.

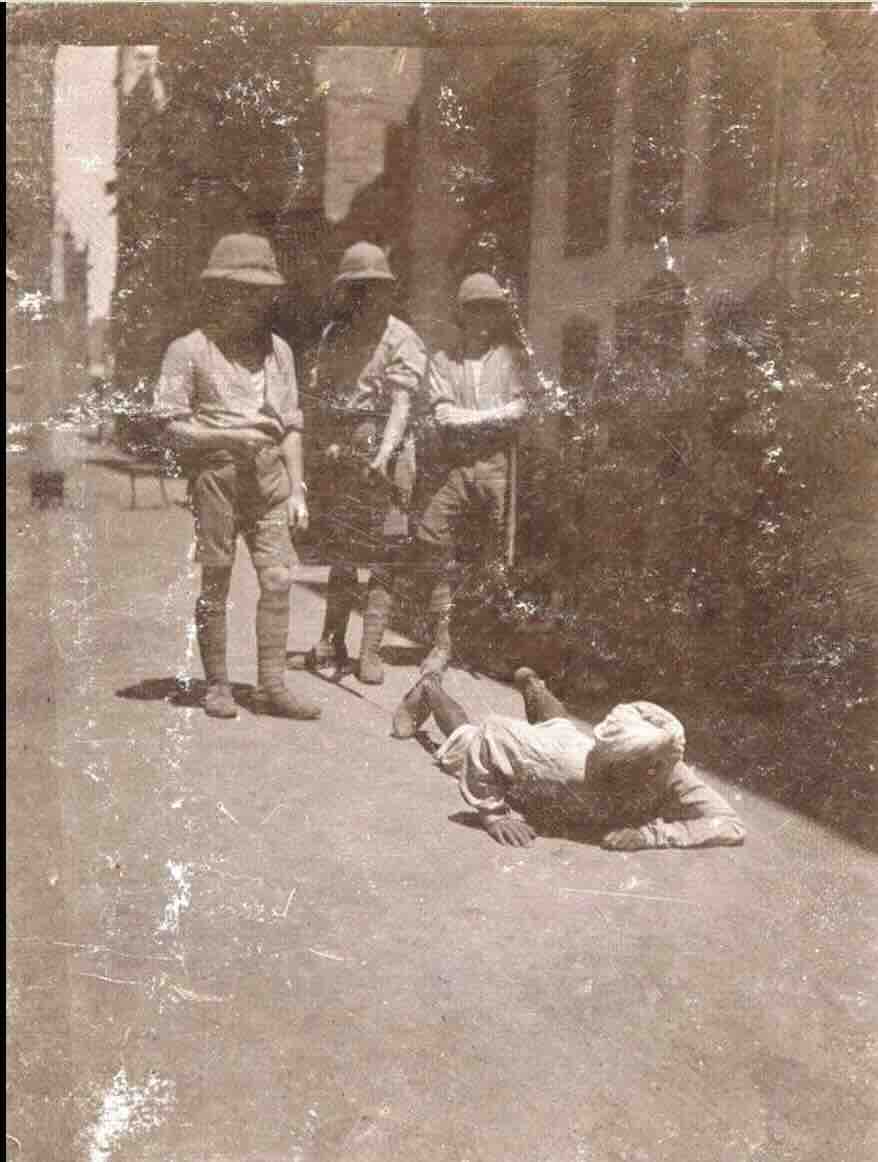

Prelude to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (Amritsar):

Prelude to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (Amritsar):

“All native men were forced to crawl the Kucha Kurrichhan on their hands and knees

as punishment, 1919″. Source: wiki.

He frankly explores his Punjabi Sikh background, and demolishes the “futile and misleading” balance sheet of “was the Empire good or bad?”. Chapter 4, “Emotional loot” gives an instructive take on the 1903 British invasion of Tibet (“the Younghusband expedition”), leading him to consider the massive stock of looted artefacts that adorns our museums and stately homes, and the bitter debate over restitution. Chapter 5, “We are here because you were there”, opens in Brighton with the story of Dean Mahomed (1759–1851) (also explored by Fatima Manji), leading to an outline of the early presence of black and brown people in Britain.

Sanghera reflects on nostalgia for the Raj, the persistent self-isolation of expat communities around the world, and their taste for British food and education; on the irony of the British search for adventure (“There is no shortage on Instagram of people who confuse travelling with having a personality”); on the lure of sexual opportunity, and prudery; and on the vanity of our claim to be “world-beating”. An intriguing insight on empire’s fetish for manliness:

It was not uncommon to find men with a stammer working in administrative roles in the Indian Civil Service—to have a position in empire instantly gave a man kudos, and a speech impediment might be overlooked for “empire served as proof for masculinity”.

Empireland is full of such instructive byways, such as the history of gin and tonic, “the cornerstone of the British Empire” (Spanish fly 1976):

Gin to fight the boredom of exile and quinine to fight malaria. How else do you think we could have carried the cross of responsibility for the life of millions without the friendly fortitude of gin and tonic?

Sanghera cites a Tweet by Helen Zaltzman:

Britain is hostile to people arriving in boats because Britain knows what happened when Britain arrived in other countries in boats.

Chapter 8, “Dirty money” continues to unearth the foundations of British wealth, while carefully identifying the complex issues. Just as balanced is Chapter 9, “The origins of our racism”:

To say Britain has a dark history of racism which influences contemporary psychology and culture […] does not preclude, for me, the fact that it simultaneously, if inadvertently, inspired anti-racism.

In Chapter 10, “Empire state of mind”, Sanghera returns to his own experience, pondering the public school system, analysing the warped psychology of Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg along with other recent Tory fatuities—but finding inspiration in the work of Edward Said. Chapter 11, “Selective amnesia”, pinpoints a major theme of troubled national histories around the world (see e.g. Memory, music, society), with a trenchant vignette on Britain’s obsession for India’s railways—citing Katherine Schofield’s hashtags #OccasionalMassacre and #ButTheRailways. He introduces James Walvin’s The trader, the owner, the slave as the single best book he has read on slavery—elsewhere he imagines putting Robert Winder, Bloody foreigners on the national curriculum.

Chapter 12, “Working off the past”, continues to explore the right-wing backlash against the convincing arguments of historians, but in conclusion he details several reasons to be optimistic. In 2023 he issued a children’s book, Stolen history: the .

Just as reasonable and constructive is his two-part documentary Empire state of mind for Channel 4 (2021). Perhaps you can also find his 2019 film The massacre that shook the Empire. Do consult his useful website.

I remain fond of this definition of patriotism from a Yugoslavian child in the 1990s, cited by Kapka Kassabova:

I love my country. Because it is small and I feel sorry for it.

* * *

Empireland makes a convenient survey of the major topics in imperialism explored by academics—and relieves bigots of the burden of reading them, allowing them to focus their fulminations on Sanghera. Despite his impartial considerations of the evidence, a counter-movement of denial soon surfaced—which he explores thoughtfully (see also here).

For what it’s worth, I am actually grateful for a great deal. […] For having had a free education at one of the best grammar schools in the country; for having attended (for free) one of the best colleges at one of the most successful universities in the world; for an NHS that cares for the people I love the most; for a welfare state that has saved my family from the most crushing consequences of poverty; for the chance to live in the greatest city on earth and work on two of the greatest newspapers in the world; for British pop music; for the glorious British countryside; for Pizza Express. But I resent being instructed to demonstrate my gratitude whenever I analyse any aspect of British life, when my white colleagues don’t get the same treatment. Yes, I have had a better life than I would probably have had in India, but I was born here, not India. I am British. I am as entitled to comment on my home nation as the next man and the endless insistence that I demonstrate my gratitude is rooted in racism. Racism which is, in itself, rooted in the fact that the children of imperial immigrants born here are not always seen as fully British.

Given that many white authors have reached precisely the same conclusions, the backlash against Sanghera and David Olusoga suggests just the kind of racism that this approach exposes, as William Dalrymple observes:

“Despite writing very similar stuff to Sathnam, I have never received a single letter like that. It is a direct result of his ethnicity and skin colour,” says Dalrymple, whose latest book The anarchy tackles the “relentless” rise of the East India Company. “You can’t really draw any distinction between what Sathnam’s writing and what I’ve written. And my books have got a free pass. There is a very serious distinction to be drawn between what he’s gone through writing what he has on empire, and me as a Caucasian writing the same thing.”

BTW, Sanghera, Olusoga, and Dalrymple are just the kind of scholars I would love to see elaborating on my speculations about the early-19th-century reversal of the black and white keys on fortepianos in the context of slavery and empire.