*Part of my strangely extensive jazz series!*

Such is my devotion to Billie Holiday that I’ve never quite been able to warm to Nina Simone (1933–2003). But my interest has been revived by listening with rapt admiration to Feeling good (1965). It opens with an all-too-brief free-tempo alap, brusquely interrupted by the incongruous sleazy riff: *

The title isn’t so ironic as it sounds. Written by (white) English composers Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse for the musical The roar of the greasepaint—the smell of the crowd, satirising the British class system, the UK premiere was given by Cy Grant in the role of “the Negro” singing the song as he “wins” the game; it was described as a “booming song of emancipation”. When the show transferred to New York the following year, the role was taken by Gilbert Price. Nina utterly transforms the song, but the optimism of its lyrics is remote from the activist songs that were becoming the core of her repertoire just at that time.

* * *

Within the milieu of the day, few musicians were angels. Jazz biographies from the, um, Golden Age tend to follow a depressingly familiar trajectory of self-destruction: pain, drugs, exploitation, disastrous choice of partners, violence, disillusion, and legal woes. Despite all these features, Miles’s autobiography is strangely inspiring, tough but never helpless (for a lengthy sample, see Miles meets Bird). White musos could be no less self-destructive—few more so than Chet Baker.

For Nina, besides wiki and ninasimone.com, I’ve been reading

- David Brun-Lambert, Nina Simone: the biography (2005).

Among documentaries is Nina Simone: the legend (Frank Lords, 1991), What happened, Miss Simone? (Liz Garbus, 2015; trailer), and The amazing Nina Simone (Jeff L. Lieberman, 2015; trailer).

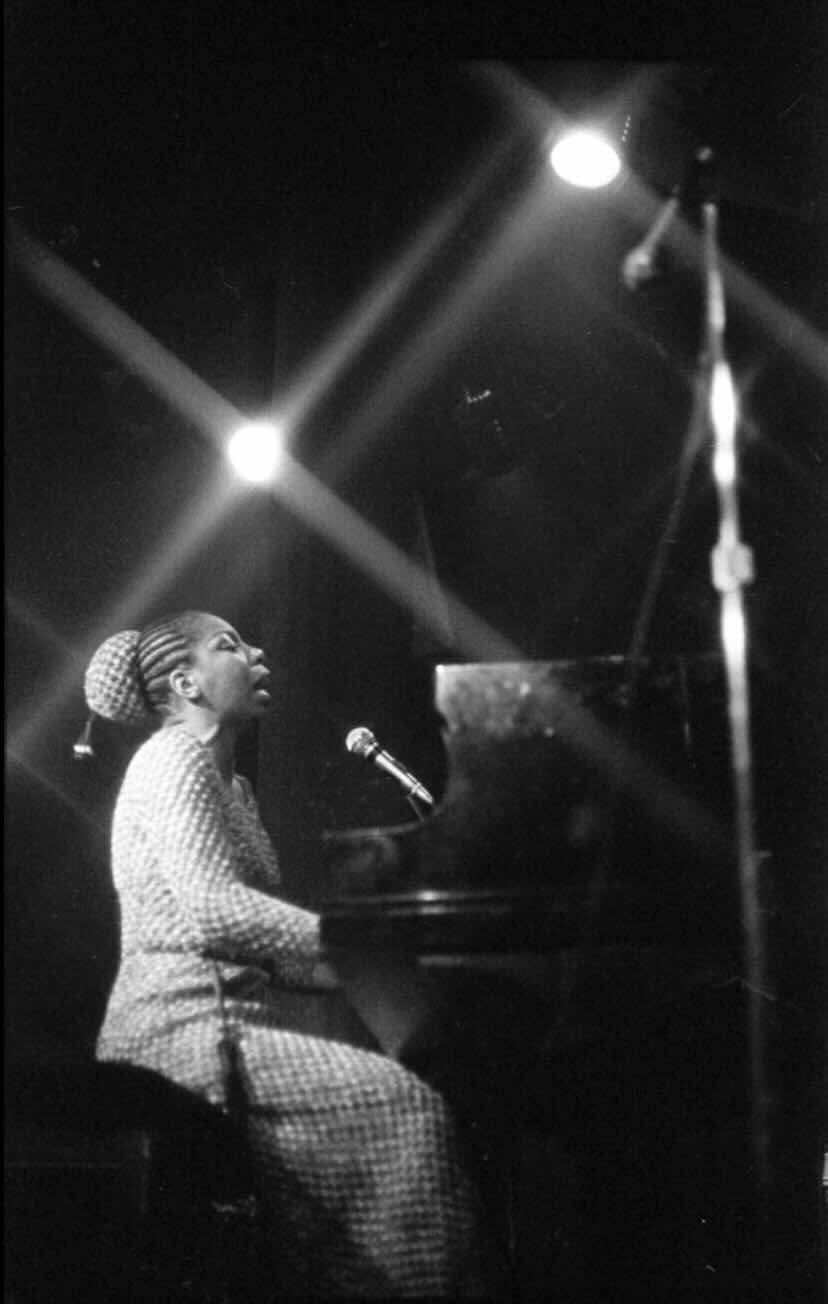

The sixth of eight children in a poor North Carolina family, Nina was a child prodigy at the piano; “Bach made me dedicate my life to music”. After graduating from high school in 1950, she seemed destined to become “the first black American concert pianist”. So the original, lasting, deep wound in her psyche was being refused admission to study at Curtis—which she attributed to racism. Thwarted in her classical ambitions, she continued to study privately with Curtis professor Vladimir Sokoloff for several years, funded with a regular gig at a nightclub in Atlantic City—only taking up singing because the job demanded it.

While Nina’s classical piano training would later give her a cachet among respectable white audiences, I seem to have reservations about singers accompanying themselves at the piano, like Ray Charles. Distinctive and original as her playing was (e.g. her “destabilising” 1969 album Nina Simone and piano), it was at a tangent from jazz: stark, based on melody, hardly admitting any harmonic interest—by contrast with her cohorts in the jazz scene like Monk, Herbie Hancock, or Bill Evans. But this musical simplicity threw greater focus on her political message.

By the late 50s, as her career was taking off, her dream of fame as a classical pianist had evaporated. The civil rights movement was growing. In Greenwich Village she began hanging out with James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, LeRoi Jones, and Lorraine Hansberry. Her 1961 visit to Lagos with Baldwin, Hughes, and others as part of a delegation of the American Society for African Culture was her first time in Africa.

Now married to a violent husband and manager, she gave birth to her daughter in 1962. Her entry into the civil rights struggle was embodied in her 1963 song Mississippi goddam. Nina’s activism, and the wider civil rights background, is extensively covered by Brun-Lambert, with detail on her involvement with Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, Miriam Makeba, the Black Panthers, riots, marches, and the whole ferment in black popular music through the 1960s.

By 1970, exhausted and disillusioned, Nina seemed to have reached the end of the road. In later life she largely avoided the USA for fear of legal battles; while still touring, she sought refuge in Barbados, Liberia, Switzerland, Holland, and France, lonely and estranged from her daughter, her relationships fraught and short-lived; among a succession of managers, some had better intentions than others. Her mood-swings and behaviour on and off stage had long been volatile, becoming ever more apparent; the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was belated. Brun-Lambert describes her as “leading a double artistic life, unable to find her own place anywhere”.

* * *

Turning to Nina’s songs—as ever, there’s a vast selection on YouTube, notably this channel—below I give a mere sample.

In her early years she sounds benign enough, like the New York Town Hall concert in September 1959, “still without trace of savagery or sexuality”, as Brun-Lambert puts it:

Still, her interpretations, such as Summertime, are distinctive. Billie Holiday had died in July that year; a couple of years earlier she had immortalised Fine and mellow in the most enthralling TV film ever. Nina sang it for her Town Hall finale.

“Her first song with explicitly black consciousness” was Flo Me La at the Newport festival in 1960 (from 20.52):

Among several appearances at Carnegie Hall, here’s her 1964 concert (as playlist):

The programme introduced activist songs such as Old Jim Crow, Go limp, and Mississippi goddam into the genteel surroundings. And she is just right for Brecht/Weill songs like Pirate Jenny!

Singing The house of the rising sun at the Village Gate in 1961, she sounds rather mellifluous:

By 1968, live at the Bitter End Café, her voice is harsher and more experimental:

The final number on her troubled 1965 album Pastel blues (here, as playlist) is Sinnerman, “about despair, disenchantment, disillusionment in the face of a situation that offers no alternatives but flight or prayer” (Brun-Lambert). Before that comes Strange fruit, just as visceral as Billie’s 1939 recording and 1959 performance. Nina’s concert in Antibes that year included some songs from the forthcoming album—opening with a disjointed intro that segues into Strange fruit:

And here’s Four women, live in 1965:

After the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968, she sang Why? (The king of love is dead)—here’s a full version live that year:

In 1967 she recorded I wish I knew how it would feel to be free—here’s her 1976 Montreux performance:

Again, I find some of these casual piano accompaniments, and even her voice, disconcerting—but maybe that’s the point.

That’s probably enough to outline the story of Nina’s heyday; in her later career she largely repeated such standards—after the original creative impetus had diluted, and as her mental troubles escalated. She had been touring in England since 1967—it’s worth hearing her live at Ronnie’s in 1985:

To encapsulate ecstasy and pain, for me it’s always going to be Billie… I may be romanticising the devotion of jazzers to their art (cf. the wonderful image of Donald Byrd practising on the subway), but I detect no inkling of any such devotion in Nina: any musical discipline that she practised seems to have been at the keyboard. She formed no bonds with her fellow musicians.

While one gets little impression that she honed her vocal skills, in early recordings like Black is the color of my true love’s hair and Wild is the wind (in the 1959 Town Hall concert) she sounds genuinely intimate, even sweet—far removed from her later image. Still, music is about society: Nina’s voice developed into a genuine expression of the troubled times, part of the necessarily strident style that emerged from the civil rights struggle.

Under A jazz medley, see e.g. Green book, Detroit 67 and Memphis 68, as well as A Hollywood roundtable, The Tulsa race massacre, and Black and white.

* Feeling good has been much covered—rather than featuring other versions, here’s Trane in 1965:

And although nothing can compare with the raw emotion of being black in those years, here’s Andrea Motis in 2012:

Not being pedantic or anything [Uh-oh—Ed.], the title seems to be cited more commonly as Feeling good than as Feelin’ good (zzzzz). Cf. I got a woman, note here.