Complementing updates by Frank Kouwenhoven in the new CHIME newsletter (subscribe here, under Newsletter) on silk-and-bamboo music, I also appreciate two further field reports from him, again written in his communicative style. First he writes on huar 花儿 song festivals in Gansu and Qinghai provinces of northwest China. [1]

Part of the wider phenomenon of shan’ge “mountain songs”, huar has long been a hot topic in Chinese folk-song studies. With his late lamented partner Antoinet Schimmelpenninck, Frank made fieldwork trips there from 1997 to 2009. Do read his substantial chapter

- “Love songs and temple festivals in northwest China” in Music, dance, and the art of seduction (2013, soon also to appear on his website), which he co-edited with James Kippen—altogether a fine volume, with a particular focus on India.

In a rapidly changing society, Frank has recently embarked on a restudy, which he outlines with engaging vignettes in the newsletter.

Though huar (an umbrella term) has long been commodified, with leading singers recruited to regional song-and-dance troupes to perform on stage, [2] Frank characterises its local folk basis as part of “the universal triangle of music, sex, and religion”. As often, the study of such festivals should be carried out not only by musicologists but by ethnographers and scholars of ritual. They should also be incorporated into the thriving field of Amdo studies, [3] addressing a complex ethnic mix—Han Chinese, Tibetans, Hui and other Muslim groups, Dongxiang, Bao’an, Salar, as well as various Monguor-speaking groups. Under the current censorship regime within China, and for a region long troubled by ethnic tensions and poverty, one can hardly expect frank coverage of religion or sex—or indeed politics.

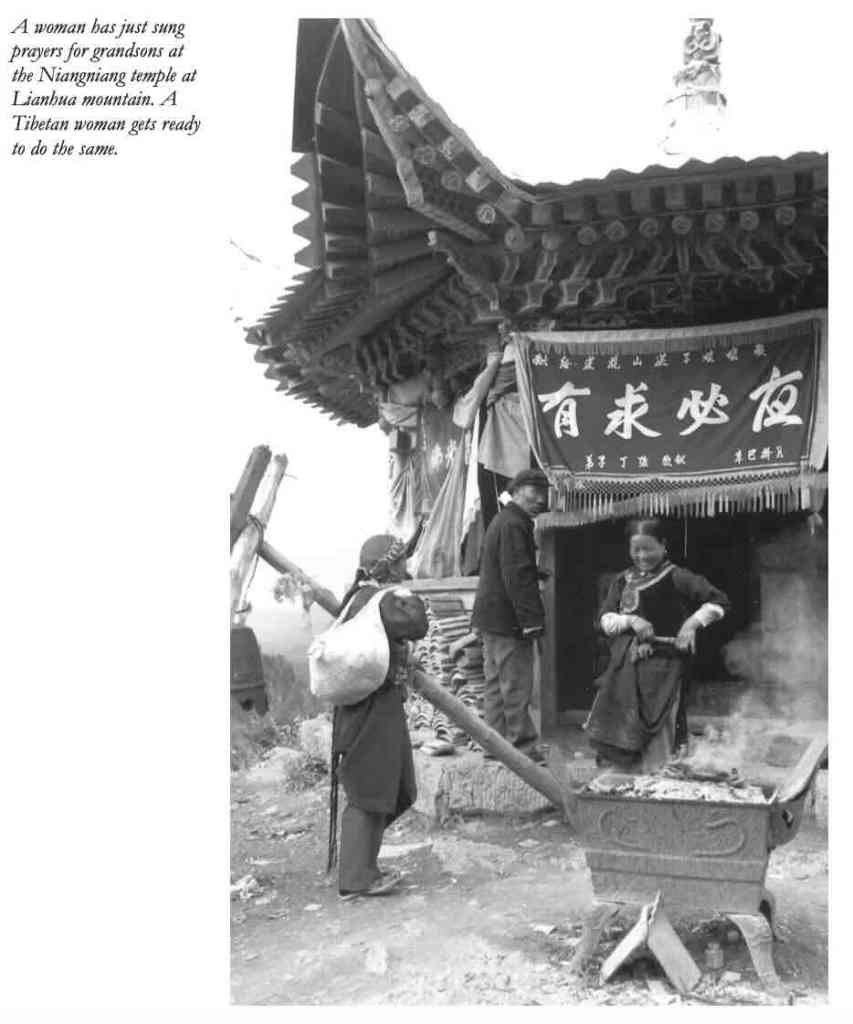

In 1993 Xi Huimin listed nearly one hundred festivals for Gansu and Qinghai (reproduced in Qiao Jianzhong, vol.1, pp.125–8); by 2013 Frank provided a map of 213 festivals in south Gansu alone (Music, dance, and the art of seduction, p.158). The largest and best-known festival is that of Lianhuashan. As he observes, the content of every festival is shaped by local needs and circumstances. Motives for attending include entertainment, contact with the gods, political affairs, and solving social problems, all closely intertwined.

Festivals are not merely places for pilgrimage, prayers, and chance encounters with strangers. They are major social events, combining markets, opera plays, disco dancing, kung fu movies, sooth-saying ceremonies, acrobatic shows, horse races, ritual processions of local gods, prayer sessions and a great deal more.

But the Chinese media

usually present these songs as a harmless form of musical entertainment, and often refer to the temple festivals in which they are sung as ‘hua’er festivals’, as if the songs are unrelated to the ritual settings, and void of religious connotations.

Still,

Some scholars who ignore or deny connections between hua’er and temple worship may do so not out of real conviction, but mainly in order to protect hua’er culture: religion is a politically sensitive topic in China, and in the past several local ritual traditions are known to have been forbidden by the authorities after details about them had been published in academic studies.

Frank also notes the Buddhist and folk-religious songs performed inside the temples, as at the Upper Bingling temple festival (pp.127–34).

As ever, it would be good to glean material on the maintenance of such local events through the Maoist decades (cf. Sparks). Even

during the Cultural Revolution, people went on singing at the risk of being arrested or attacked by Red Guards. Complete battles took place between hua’er singers and Red Army soldiers at Lianhuashan after the government had forbidden the festival there.

Frank’s chapter goes on to discuss courtship and sex, sacred singers in mythology, and fertility cults; power, authority and competition at temple festivals; and ethnicity.

Hornblowers at the head of the annual procession of the eighteen gods in Xincheng, 1997.

His recent fieldwork focuses on the festivals at Erlangshan (Minxian) and Xincheng. As in his earlier chapter, he notes how processions of the gods often result in violence. In Xincheng,

We recorded violence between three such groups at one spot near the south gate, resulting in bloodshed, chaos, people squeezing one another, and furious quarrels flaring up between individual men. A big police force had been kept on standby. It soon arrived on the scene, some twenty, thirty men including national guards, but they were unable to calm down the mob.

A bunch of daredevils had used their sedan chair as a weapon, pushing and chasing another sedan chair down the road. It was as if the gods themselves were taking up a fight. The dense crowd began to move, shouting, gesturing, and the assembled policemen were involuntarily pushed along.

Sedan bearers start a fight in Xincheng.

Running up the stairs of the temple with a sedan chair

(cf. mediums’ sedans in Shaanbei).

Among recent changes on Erlangshan, Frank notes that some singers themselves now favour amplification:

It made their singing much louder, but obviously undermined the option for most people to join in spontaneously with a phrase or a couplet, precisely the thing that had made the whole tradition so endearing: the free-flowing exchange of lyrics, an ever ongoing battle of wits… Now, the person in a crowd holding the microphone would decide whom to give it to for a reply, with all others essentially being excluded from the sung conversation.

Frank also documented devotional songs in nearby villages. While musicological analysis is always desirable, I’m keen to see more research on the ritual aspects of these cultures in changing society.

In Minxian he also attended a grand stage show, illustrating the secularisation and commodification of local culture—leading nicely to his next topic, which I introduce here.

[1] Frank’s 2013 chapter includes a useful bibliography of works on hua’er in Chinese and English. Among publications are several surveys by Qiao Jianzhong (in vol.1 of his works), as well as studies by Du Yaxiong and regional scholars such as the folklorist Ke Yang. One should also consult the Anthology folk-song volumes for Gansu and Qinghai. Rather than the conventional rendering hua’er, I favour the form huar. Links to further posts on Gansu here.

[2] Among such “stars” of huar was Zhu Zhonglu 朱仲禄 (1922–2007), subject of several CDs (and tracks on the archive set Tudi yu ge); this documentary, though straight-laced, is representative of the official image.

[3] Note the Amdo Research Network, and references here.