By way of reminding you of my series on the great Gustav Mahler, some brief comments on the three symphonies of his performed at this year’s Proms, while I consult Norman Lebrecht’s handy guide Why Mahler?, marvelling at Mahler’s busy conducting schedule amidst the tribulations of his personal life.

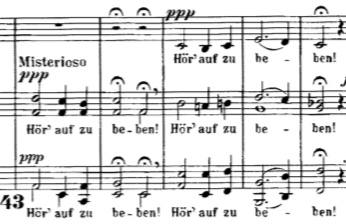

Nothing can be so overwhelming as the 2nd symphony, which I heard on what was once called the radio. I find it hard to imagine how Mahler could have written anything after this. As to the 3rd, after the middle movements (akin to those of the 7th), the radiant finale dominates one’s image of the piece.

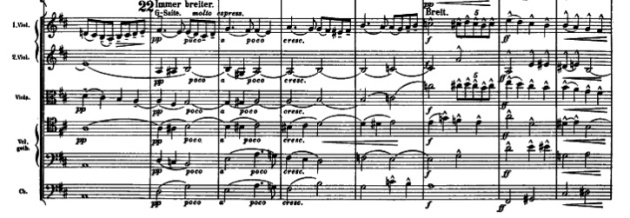

Hearing a live performance of the 5th is just as moving. The mellifluous Concertgebouw orchstra was conducted by Klaus Mäkelä (for the Concertgebouw’s Mahler 9 in 2022, click here)—it is televised on iPlayer.

I muse on the ravishing slow movements of this period in Mahler’s life: that of the 3rd as the culmination of the symphony, the Adagietto of the 5th all the more effective within the context of the whole; no less moving are those of the 4th and 6th (the latter, to my taste, still best placed third in the order of movements).

My Mahler series includes performances and recordings of his seminal works by some of the great interpreters. See also The art of conducting.