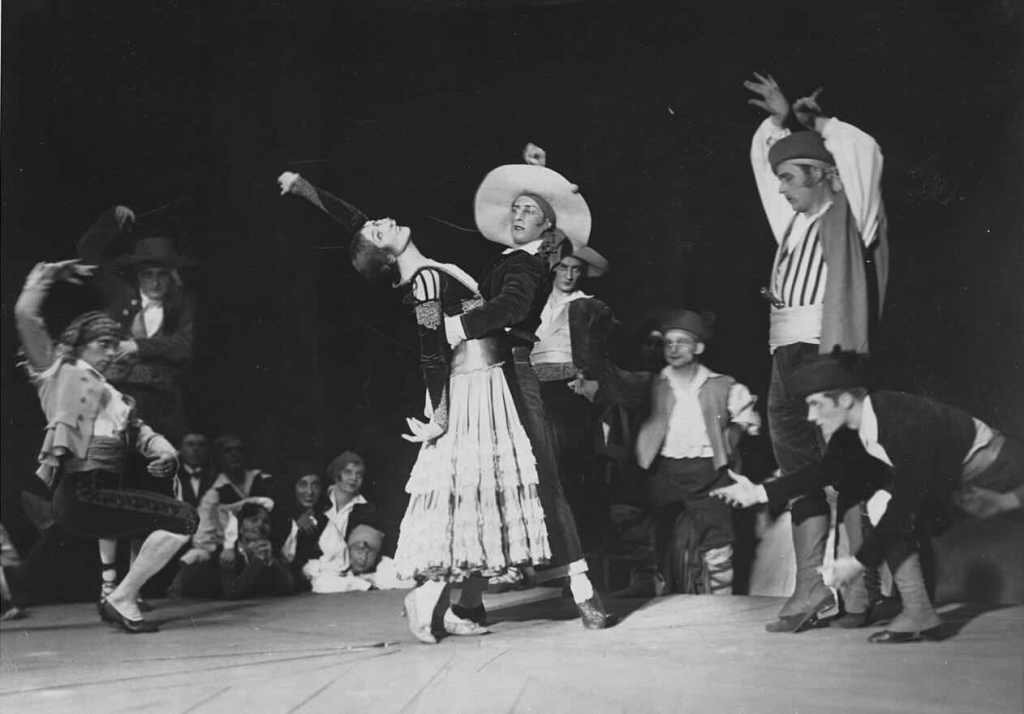

Ida Rubenstein leading the original 1928 production of Boléro. Source.

Ravel’s Boléro and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring have become concert “classics”, but they are challenging in very different ways. It was exhilarating to hear both in the same Prom the other day.

For The Rite, I refer you to various posts, starting with my own epiphany under Boulez in The shock of the new. By comparison, Boléro (also composed for a ballet) may merely seem like easy listening, but the concept is just as original, with our ears kept engaged by the rhythmic fluidity of both segments of the melody * over one long, relentless crescendo. I’m reminded of Roger Nichols’ characterisation, quoted in my page on Ravel:

the repetitive obsession that opens out on to notions of death, madness, destruction, and annihilation, as if the composer had had an apocalyptic vision of the end of the world.

Of course listeners will respond in different ways. Even if such a message is merely latent, Boléro can and should be a somewhat unsettling experience.

Again, note my Ravel page, along with posts under Ravel, Stravinsky, and Proms tags. See also Perfect Pitch, and posts on minimalism.

* Another party game: the two sections of the melody are deceptively simple, so one might suppose that after hearing so many repetitions, we would be able to reproduce it quite accurately from memory, even after a single hearing—and most of us have heard the piece many times. It becomes more achievable if we intentionally set out to memorise it (and for some it may help to consult notation), but even then it may still be a challenge—the first half of the opening section alone may prove surprisingly difficult to reproduce by heart. After Hašek, my usual prize of a small pocket aquarium…

Of course, it’s not to be compared with memorising a Brahms concerto, but its apparent simplicity, with virtually no harmonic props, make it all the more intriguing as an exercise. Cf. Conducting from memory, and On “learning the wrong music”.