The current floods in north China are severely affecting counties on the Hebei plain such as Zhuozhou, Laishui, Bazhou, Xiongxian, and Anxin, whose villages were our fieldbase through the 1990s (see Menu under Hebei).

While the climate crisis intensifies, faith in the protection of the gods has diminished under the assaults of Maoism and capitalism. Those villages relatively unaffected by natural disasters traditionally attributed such immunity to the divine blessings afforded by their ritual association—as in Gaoluo, where the floods of 1917 and 1963 are still part of popular memory. The 1963 flood came during a brief cultural restoration between famine and the Cultural Revolution (see Cai An’s story here).

But whether or not villages still have active ritual associations, the current flooding is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods. Political decisions made to protect key economic areas (e.g. here, here) have also led to protests.

* * *

Conversely, the main affliction of north China is drought—as Li Manshan observes at the start of our film, “nine droughts every ten years”. For this the folk recourse for villagers was to make collective processions to pray for rain. Hence the importance of the Dragon Kings and their temples (note images on the website of Hannibal Taubes), and related deities like Elder Hu in north Shanxi.

As in much of the third world, for the fieldworker it is a salutary reminder of the precarity of life to wash one’s hands and face over the day in a single shared enamel bowl of water fetched from the well.

Fetching Water, Zhuanlou village funeral, Yanggao 1991.

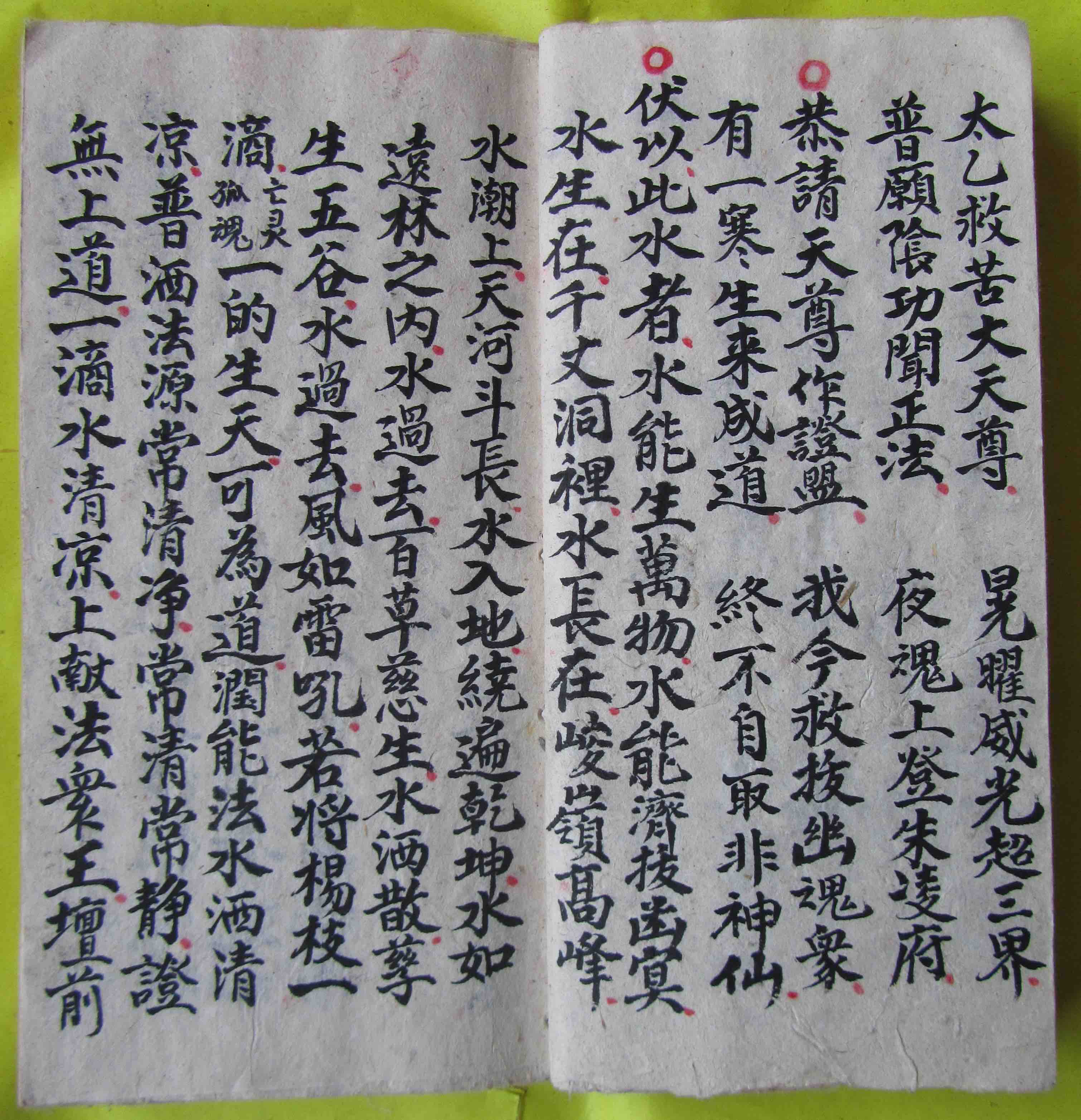

Shishi quanbu Bestowing Food manual, copied by Li Qing,

segment on water from line 5, to be recited.

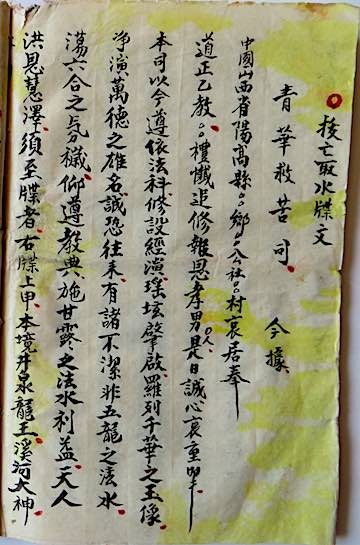

Template of memorial for Fetching Water to Release the Deceased, no longer displayed.

From Li Qing’s volume of miscellaneous ritual documents.

As to ritual, Fetching Water (qushui 取水) or Inviting Water (qingshui 請水) segments are common throughout China, for temple fairs, domestic blessings, and funerals, parading to a nearby well or stream. One might expect them to be especially meaningful in the drought-prone north. Inviting Water is common in temple ritual and in south China (e.g. Hunan), but I have hardly heard of it in northern folk ritual, where Fetching Water is standard (for Yanggao in Shanxi, see my film Li Manshan, from 41.06, and the DVD Doing Things; see also Daoist priests of the Li family, pp.67–8, 209–10).

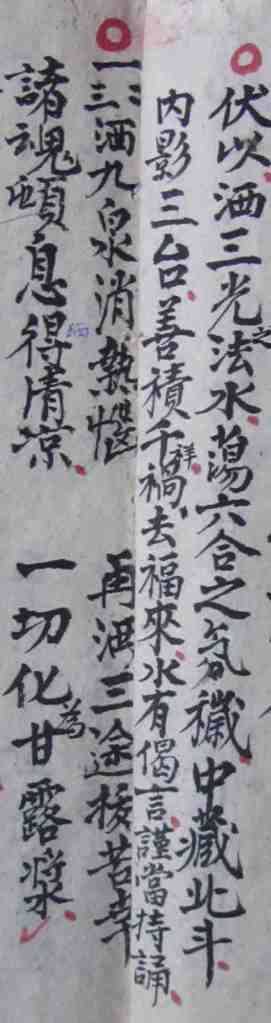

The text on the right (“I declare, sprinkling the ritual water of the three lumens”) is a shuowen introit preceding the Gātha to Water on return to the soul hall.

Though running water has gradually been reaching more villages since the 1980s, such rituals continue to be a significant component of the whole symbolic repertoire of ritual sequences, perpetuating historical memory.

For water, religion, and politics in barren Gansu, see The temple of memories.