Two new books

Among many stimulating articles on the site of the China Books Review, two caught my attention, on the lives of Chinese women.

It’s an important topic, much studied—when socialist revolutions always promise more for women than they deliver. [1] Both reviewers point out the increasing sensitivity of broaching such issues: as Irene Zhang observes, such works are all the more notable “in a Chinese media landscape increasingly hostile to feminists, and with state organs intent on stamping out grassroots activism”.

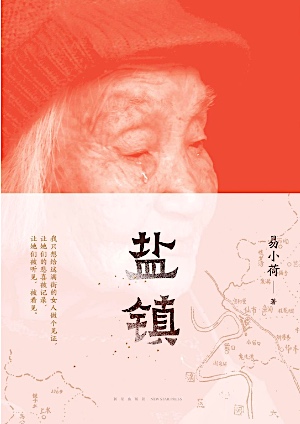

That comment comes from Zhang’s review of

- Yi Xiaohe 易小荷, Yanzhen 盐镇 [Salt town] (2023).

The book gives “profiles of ten women of different generations, occupations, and social statuses” in the small town [2] of Xianshi in Sichuan—“a former brothel madam, a cotton fluffer’s wife, a hotelier, a lesbian village cadre, a struggling mother, a butcher’s daughter, a beautician, a divorced university dropout, an orphaned migrant worker, and a 17-year-old prostitute.”

Zhang observes:

Interwoven through the ten profiles are themes that define rural womanhood: discrimination, domestic violence, family duty, and resilient entrepreneurship.

As Yi Xiaohe sums up,

Life in Salt Town is a series of tiny cuts and open wounds. Women are trying to stanch the bleeding, while men are adding salt to the wounds.

Zhang’s review makes some salient [sic] critical points, concluding:

Rural Chinese women live with deep intergenerational trauma from centuries of deprivation and state violence, with few guarantees of institutional protection. They still struggle to move upward in a stubbornly discriminatory society all too happy to exploit their labor. While tackling the topic is commendable, in Salt town the big-city writer looks at the small town the same way we look at this history today—from a safe distance. What hurts Xianshi’s women is still at large.

* * *

In the same issue is a review by Zheng Churan—one of the “Feminist Five”:

- Zhu Xiaobin 朱晓玢, Tade gongchang buzaomeng: shisanwei nügong dagong shi 她的工廠不造夢 ──十三位深圳女工的打工史 [Her factory makes no dreams: the working stories of thirteen Shenzhen female workers] (2022).

Whereas Salt town soon became a bestseller in the PRC, Zhu’s book, published in Taiwan, is banned in mainland China. It tells the stories of thirteen women—as Zheng observes, a more diverse sample than in Lesley T. Chang’s 2008 book Factory girls: from village to city in a changing China.

Her Factory Makes No Dreams tells the stories of individual rebellion by female workers: escaping from arranged marriages; choosing to live alone instead of in abusive domestic situations; going on strike against unfair working conditions; and defying patriarchal society by participating in feminist movements against sexual harassment.

The review goes on:

Reporting the stories of female factory workers inevitably touches upon sensitive topics that can provoke the ire of authorities: gender inequality; exploitation of workers; “stability maintenance” measures to crack down on protest; an unfair household registration system; and shocking wealth disparity.

In conclusion, Zheng writes:

Where once the voices of female workers were heard, now the Chinese state has dismantled these windows into their lives. This is lamentable for the Chinese people, not only because they no longer have the opportunity to hear the stories and demands of workers from different classes, but because a greater crisis lurks ahead. With declining employment rates in China, low birth rates and escalating social conflict—when stability maintenance policies can no longer quell the anger of those who face injustice—without these bridges to the public, will the people still be able to navigate their difficulties peacefully and without violence?

[1] Among many authors to read in in English are Elisabeth Croll, Gail Hershatter, Harriet Evans, and Leta Hong Fincher. For my paltry observations on the lives of women in China (mainly in the rural north) and elsewhere, click here; see also Chinese translations of Elena Ferrante and Sally Rooney.

[2] Small towns (zhen), or townships, between the county-towns and the villages, are an important nexus: see e.g. Dong Xiaoping here.