Reflecting on the popularity of Zen in the West, and my own youthful explorations, in my post More East–West gurus I gave a brief introduction to R.H. Blyth (1898–1964) (wiki, and useful sites here and here), but he deserves more.

The initials stand for Reginald Horace—both the given names and the initials being a sign of the times. Always of an alternative bent, a vegetarian and adherent of George Bernard Shaw, in 1916 he was imprisoned in Wormwood Scrubs as a conscientious objector. A musician, he was a devotee of Bach—I’m not aware that he ever encompassed noh and kabuki drama, or the shakuhachi, but it’s an intriguing idea.

“Fed up with the rigidity of Britain’s class system” * (Robert Aiken’s recollections are worth reading), in 1925 Blyth went to live in Korea, teaching English at Seoul University, learning Japanese and Chinese, and studying Zen. By 1940 he had moved to Japan, teaching English at Kanazawa University, but in 1941 he was interned again, now as a British enemy alien. After the war, “he worked diligently with the authorities, both Japanese and American, to ease the transition to peace”. In 1946 he became professor at Gakushuin University.

Like his mentor the great Zen master D.T. Suzuki, Blyth’s work influenced the post-war Beat generation like Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, and Allan Ginsberg. Besides Alan Watts, other devotees of Blyth’s work included Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller, and Christmas Humphreys (another challenging dinner party), all of whom I admired in turn. For Steinbeck’s and Salinger’s absorption in oriental mysticism, see here. Salinger wrote:

Blyth is sometimes perilous, naturally, since he’s a highhanded old poem himself, but he’s also sublime.

In my teens I was much taken by

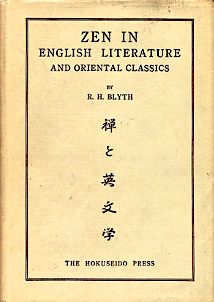

- Zen in English literature and Oriental classics (1942), written while he was interned in Japan (446 pages, full text here).

Blyth finds “expression of the Zen attitude towards life most consistently and purely in Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Dickens, and Stevenson, adding “numerous quotations from German, French, Italian, and Spanish literatures”. He devotes a whole chapter to Don Quixote, and four chapters to Non-attachment; further chapters cover Death, Children, Idiots and Old Men, Poverty, and Animals.

I was already far more amenable to the oriental classics (notably haiku, his main exhibit) than to all the Shakespeare and Wordsworth, but I got the point that enlightenment didn’t necessarily have to be sought in remote oriental mountain hermitages—as the Daoist and Zen masters indeed remind us.

The flaws in his ouevre are recognised. The most pervasive criticism, which leaps out from every page, is that, in the words of Patrick Heller, “Blyth’s work exhibits a fundamentally distorted Orientalist view of Japanese literature and religion”. And, according to wiki:

Some also noted that Blyth did not view haiku by Japanese women favourably, that he downplayed their contribution to the genre, especially during the Bashō era. In the chapter “Women Haiku Writers” Blyth writes:

Haiku for women, like Zen for women—this subject makes us once more think about what haiku are, and a woman is…Women are said to be intuitive, and as they cannot think, we may hope this is so, but intuition…is not enough… [it] is doubtful… whether women can write haiku.

Discuss (not). Oh well—that was then, this is now.

* * *

Besides Zen and Zen classics (five vols, 1960–70), Blyth went on to publish Haiku (four vols, 1949–52) and History of haiku (1964—five of eight planned volumes).

And a spinoff that is more significant than I realised is his work on senryū, ** the cousin of haiku penned from a more humorous, human angle (pdf of his 1949 book here).

Blyth’s immersion in Japanese culture was admirable, and he exerted a considerable influence on the post-war generation in search of the Wisdom of the Mystic East…

See also this roundup of posts on Japanese culture, including some largely jocular haiku in English—a later trend of which Blyth may or may not have approved.

* Blyth’s search for a less rigid class system would seem to be a case of “out of the frying pan into the fire”, but if the class system of his new home was just as rigid, at least it wasn’t British?!

** I’ve awarded italics to senryū, whereas haiku has surely become roman—cf. sarangi and sitar?!