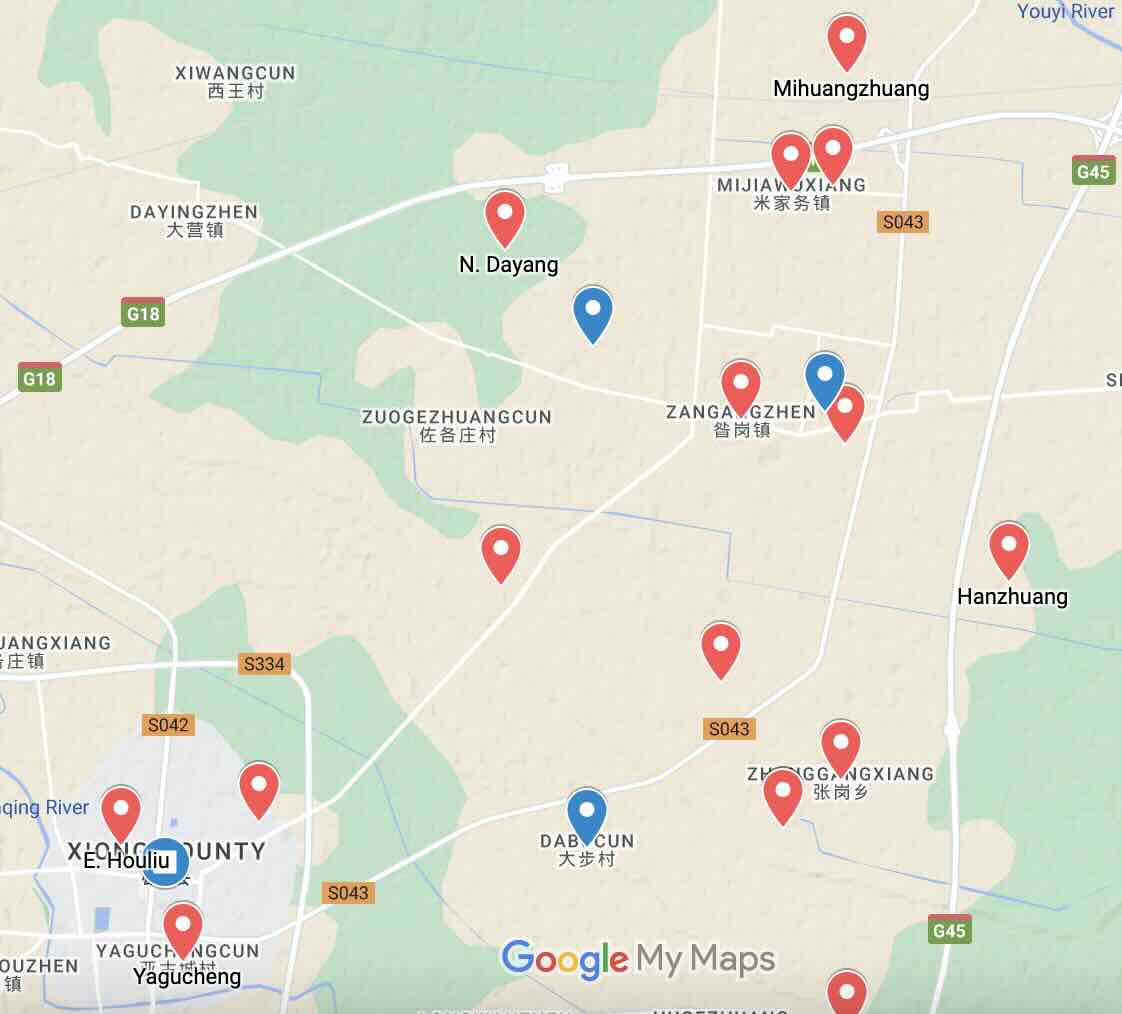

Our 1990s’ project on village ritual groups on the Hebei plain just south of Beijing (overview; fieldnotes listed here, under Hebei) revealed a wealth of evidence for sectarian activity. Our visits to Xiongxian county (click here, with map) focused on the ritual associations of Hanzhuang, Gegzhuang, and Kaikou villages, but on a “gazing at flowers from horseback” trip to the Mijiawu district in 1995 we could see that there was much to learn there too. I’m prompted to revisit our notes after reading a recent article in Sixth tone, subject of the second half of this post.

Of the five villages in Mijiawu, both East and West villages formerly had Great Temples (dasi 大寺). The Laofomen 老佛門 sectarians in North village had learned from the Buddhist monks of the Great North Temple in West village, who performed rituals among the folk. But the temple, and the monks’ instruments, were destroyed during the Japanese occupation.

At Mihuangzhuang the senior Cheng Wanxiang made an articulate guide to the history of the village ritual association (known by the confusing term yinyuehui 音樂會, “music association”—as well as my overview, note my comments on recent Chinese attention to my work on Gaoluo). The members were originally Laofomen sectarians. The repertoire of their shengguan wind ensemble music derives from three nearby villages: Mijiawu, Hanzhuang, and Bandong. After the end of the Cultural Revolution they restored around 1981, despite a lack of support from the village brigade and the disapproval of the county authorities. Cheng’s family were poor, but they forked out the money to buy sheng mouth-organs, so the others were moved to bring out their grain to buy a drum and other instruments. As he commented, “Village life is so monotonous—the association helps us handle (tiaojie 调节) life, but the brigade won’t support it. The association’s raison d’etre is to do good, and learn proper behaviour (xingshan 行善, xue guiju 学规矩).” Cheng Wanxiang himself went to invite his fellow villagers to study the music—ironic, as he notes, the teacher inviting the pupil! But still no-one cared to learn. Even so, in 1995 there were fifty or sixty households “in the association”.

Some association members.

Some association members.

Like Xie Yongxiang in Hanzhuang, Cheng Wanxiang made some fine distinctions. The temple fair over three days around 3rd moon 15th was known as Granny Assembly (Nainai hui 奶奶會) or Favourable Incense Assembly (Shunxiang hui 顺香會), made up of old women. A tent was set up, with paintings of Wusheng laomu and “Granny” (Houtu) (see The Houshan Daoists), and the association helped out. Again, the purpose of the Favourable Incense Assembly was to “do good” (a common theme, as villagers denied “superstitious” elements), but they stopped activity in 1937. The association hadn’t made the pilgrimage to Houshan, but some of the old women had.

The Laofomen sect was also distinct. They cured illness by using tea-leaves and qigong, not incense. They too “did good”, not accepting gifts; there was no charge—they even fed members. Their main scriptures were Dafa jing 大法經 (for Presenting Offerings, shanggong 上供), “precious scrolls” to the God of Earth and the Ten Kings (Tudi juan 土地卷, Shiwang juan 十王卷), as well as the ubiquitous Incantation to Pu’an (Pu’an zhou 普庵咒). Some were “recited scriptures” (nianjing 念經), some “wind-music scriptures” (chuijing 吹經). They kept performing them after the Japanese invasion, but less well. So the yinyuehui also served the Laofomen. After Liberation the Laofomen was suppressed, but its members continued curing illness. Their scriptures were burned at the start of the Cultural Revolution.

* * *

I’m reminded of these notes not only because since 2016, these villages are being swallowed up in the vast new XiongAn airport, but since Mibeizhuang is the subject of a recent article in Sixth tone about the village’s erstwhile thriving trade in funeral paraphernalia.

Welcome to the so-called “Wall Street of the underworld,” where businesses stock approximately 10,000 different types of goods, such as paper flowers, effigies, and elegiac couplets, for traditional Chinese funerals and memorial ceremonies.

In villages, towns, and cities around China, individual familes (such as household Daoist Li Bin with his wife in Yanggao, north Shanxi) often open funeral shops, and some run thriving businesses. In Mibeizhuang the local memorial supply industry didn’t begin to take shape until around 2003.

Elderly residents credit this transformation to Yang Wenyuan, who at the time was Party secretary of Xiong County, where the village is located. He oversaw development of the main street, attracted suppliers and buyers, and helped organize the local workforce, dividing labor between production and sales.

I’m incredulous to read that Mibeizhuang “accounts for 90% of China’s funeral supplies market, recording an annual output of about 1 billion yuan ($137.94 million)”.

Forty-something Li and his wife used to sell donkey meat burgers in downtown Baoding, but they decided to return to their native village in 2014, renting a 60-square-metre space to open a one-stop supermarket offering “almost anything one might need in the afterlife.” The shelves are stocked with all kinds of paper products: beverages, vegetables, cell phones, televisions, cooking gas cylinders, electric-powered farm tricycles, and passports. The store also receives orders for custom-made products, such as full-size replica camouflaged tanks; luxury goods including Lamborghinis, Porsches, Mercedes, and Harley-Davidson motorcycles; and even a scaled-down three-story villa with a butler, maids, and a courtyard.

However, recently there has been a downturn in the market,

stemming from two major factors: policy and progress. In recent years, local authorities across the country, including in Baoding, have introduced “civilized memorial” regulations targeting the manufacture or sale of “feudal and superstitious” goods such as spirit money and other paper offerings. […]

In late March, local vendors received a text notification about the Baoding Civilized Memorial Initiative on their cell phones. Like similar policies rolled out by cities in Jiangsu, Shandong, Guizhou, Hunan, Shaanxi, and other provinces, the initiative aimed to prohibit the production and selling of “feudal and superstitious” memorial supplies. The penalties for violating these new regulations include steep fines and the confiscation of goods.

While this directive is having an impact on business, “there are too many traders, so it’s difficult to tackle everyone,” and people are quick to find ways to bend the rules. I’ve discussed the influence of official directives on local ritual cultures in posts on Shandong and Shanxi.

In addition, the emergence of new technologies is providing people with cheaper and more sustainable options for funeral and memorial ceremonies.

Anyway, after our notes on the history of sectarian activity in Xiongxian, I was intrigued to find this further update on the constantly shifting ritual scene there.