The story of how European missionaries introduced Western Art Music to the Qing court in Beijing has been well documented. But there has been no scholarly consensus on how or when WAM was taken up by a wider pool of Chinese performers.

A recent book,

- David Francis Urrows, François Ravary SJ and a Sino-European musical culture in nineteenth-century Shanghai (2021),

is introduced in Sixth tone by Zhang Xiaoyi, librarian at Xuhui District where material has been discovered.

As she observes, some have traced the “first Chinese orchestra”

to the formation of the Shanghai Public Band (now the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra) in January 1879, which was headed by Jean Rémusat—“Europe’s premiere flautist”—and composed largely of Filipino musicians. Others argued that Sir Robert Hart’s brass band, founded in 1885, should be considered the earliest Western orchestra in China because its members were Chinese. And a few pointed instead to a music course taught by American missionaries at Shandong’s Tengchow College in 1876.

The French Jesuit missionary François Ravary (1823–91) arrived at the Collège St. Ignace in the Xujiahui (“Zikawei”) district of Shanghai in 1856 to direct the school choir. Now, thanks to Urrows, we know that he founded an orchestra there, using instruments shipped from Europe by Ravary’s friend Hippolyte Basuiau, a violinist-turned-Jesuit.

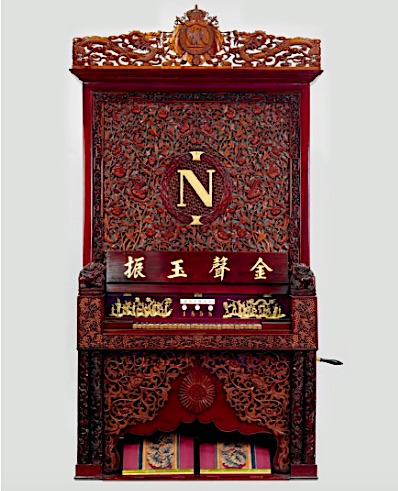

Together with fellow Jesuits Louis Hélot and Léopold Deleuze, Ravary also made his own instruments, setting up a workshop in what was then St Ignatius Church and recruiting four Chinese carpenters to help them build a pipe organ out of bamboo, modelled on the sheng mouth-organ.

Organ made by Léopold Deleuze and his team.

Deleuze and a team of Chinese craftsmen later built another organ, this time with three special stops to reproduce the sound of the Chinese xiao end-blown flute, di transverse flute, and sheng. Dedicated to the son of Napoléon III, then king of France, it is now preserved at the Musée de la Musique in Paris, though the pipes have rotted and can no longer produce sound.

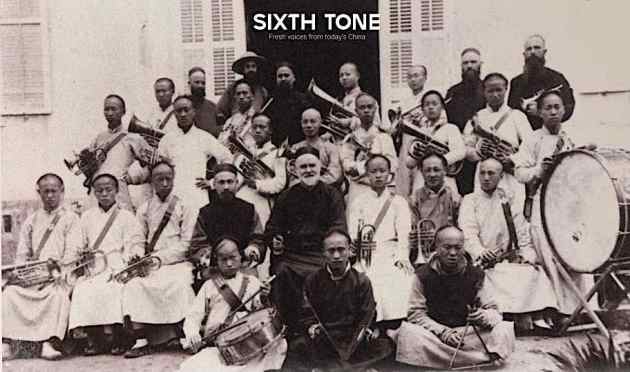

Once his instruments were ready, Ravary began recruiting Chinese students to take lessons in Western music. In 1864, when a group of orphans was moved near the school in advance of the opening of T’ou-Sè-Wè orphanage, he included them in his orchestra training as well.

After their first performance, Ravary wrote “It is fortunate that in this country, people’s ears are not as discerning as they are on the Champs-Élysées”. Once the performance ended, the nervous student-musicians gorged themselves on steamed buns.

By 1871 the orchestra was more assured: an Austrian baron enthused, “Haydn played in China by the Chinese! … We were all deeply moved.”

Still, regarding repertoire Urrows avoids getting carried away:

In my experiences in China studies, when it comes to music repertoire in the missions from the late 16th century onwards, most of what people write—and then perform—is 10% based on documentation, and 90% based on fantasy, resulting in a kind of musical chinoiserie of a New Age type. I don’t want to promote, much less add to this pile of pseudo-scholarly dreaming, pleasant as it is to listen to…

When Ravary was transferred from Xujiahui, the orchestra declined—until 1903, when the Shanghai-born Macanese Francisco Diniz and his friends organised a military band at the T’ou-Sè-wè orphanage known as the Fanfare de Saint Joseph. With Joseph Tsang, Diniz also co-edited Rudiments de musique, a textbook in question-and-answer format to teach students to play wind instruments like trumpets and tubas—apparently China’s earliest known textbook on Western instrumental music, and the earliest such book written in the Shanghai dialect.

In 1907, Louis Hermand, a Western music teacher who worked with the band, predicted that “In a few decades … we will see a Chinese child take their place among masters like Gounod and Wagner.”

All the while, of course, Shanghai was home to a wealth of musicking, including silk-and-bamboo clubs, Daoist ritual, shawm bands, local opera, narrative-singing, and puppetry. See also China’s hidden century.

I look forward to reading Prof Urrows’s book he is a fine historian. If you would like to read a broader history of the development of Western Bands in China please look at my book. “Sir Robert Hart the Musician” Pub Lulu.com 2020. It is clear that the Jesuits were the first to establish Brass Bands in China at Xujiahui.

LikeLiked by 1 person