Despite all its flaws, the vast Anthology of folk music of the Chinese peoples remains an essential starting point to survey the ritual life and soundscapes of regional folk cultures. For the province of Henan, I’ve written posts on bards and spirit mediums; now, while bearing in mind the volumes on folk-song, narrative-singing, opera, and dance, I’ve been skimming the Anthology volumes on instrumental music, where much of the material on ceremonial and ritual life appears (cf. my surveys for Fujian, Liaoning, and Tianjin, as well as Two local cultural workers):

- Zhongguo minzu minjian qiyuequ jicheng, Henan juan 中国民族民间器乐曲集成, 河南卷 (1997; 2 vols, 1,515 pages).

Though the great bulk of the volumes consists of musical transcriptions (never very helpful in the absence of available recordings), and the quality of the textual essays is even less satisfactory than in many of the other volumes, clues may be found in the terminology for regional genres and names of bands and musicians.

Henan municipalities. Source.

Henan municipalities. Source.

While the early history of musical cultures in Henan is reflected in a wealth of iconography and excavations (for which, see further Zhongguo yinyue wenwu daxi, Henan juan 中国音乐文物大系, 河南卷, 1996), the main material is based on fieldwork on living traditions. Major themes in the modern transmission of local cultures, always suppressed in PRC historiography, are poverty and the memory of trauma (cf. Memory, music, society, and Sparks). But the Anthology rarely offers glimpses of this submerged history; in the narrative-singing volumes for Hunan province I found some passages bearing on the famine around 1960 (here, and here), but Henan suffered even more grievously, and looms large in studies of the national catastrophe. *

Shawm bands

By now we are used to finding the Anthology‘s most substantial coverage devoted to “drumming and blowing” (guchui), referring to shawm bands serving life-cycle and calendrical ceremonies. After the general survey (pp.9–11), the introduction to these bands (pp.29–35) preceding the many transcriptions is brief and formulaic.

Xiangbanzi, Sanbi, Xinyang

Shawm band, Xunxian funeral

Shawm band, Linxian funeral

Bands are commonly known as xiangqiban 响器班, and the shawm as dadi ⼤笛, often supported by the related wind instruments xidi 锡笛 and menzi 闷⼦. Many bands have added the sheng mouth-organ since the 1930s.

The introduction confirms the lowly outcast status of the musicians in the “old society”. Locals distinguish those who only play shawm (qingshui 清水) and those who also work as barbers (hunshui 混水). In Zhoukou municipality alone, 300 bands were documented at the time of compilation.

In sections near the end of vol.2, following introductions to the Song family shawm band of Kaifeng (a kind of folk academy for the state troupes) and the shawm band of Shibukou in Lankao county (pp.1422–23), brief biographies (pp.1425–35) contain further clues. Many of these musicians came to the attention of collectors through being absorbed into the state troupes, but any of their lives would make an illuminating in-depth social study—incorporating the history of Maoism, the famine, and the 1980s’ reforms.

Guanzi player, Tianshan village, Longmen, Luoyang

Xun ocarina player, Puyang

Shang Yuanqing on shawm, Neixiang

Shengguan players, Xinzheng.

Female members of shawm-band families seem to have begun taking part earlier than further northwest (cf. Hubei: The Chinese shawm: changing rural and urban images).

Chuida in Neixiang county, and Bayin louzi of Zhoukou

Sixian luogu, Shangcheng county

Shipan, Yima municipality.

Also subsumed under the rubric of “drumming and blowing” are groups in central and northwestern Henan led by guanzi oboe or dizi flute: the shipan ⼗盘 of the Luoyang–Sanmenxia region (named after its ten-gong yunluo, and akin to ritual shengguan ensembles just north); the amateur bayin hui ⼋⾳会 around Jiaozuo (with a more diverse instrumentation) and bayin louzi ⼋⾳楼⼦ of Zhoukou municipality (named for their processional sedan), once patronised by Shanxi merchants.

Clues to the Shanxi origins of the Bayin louzi in Zhoukou.

String ensembles

By comparison with wind bands, string ensembles (“xiansuo”) are rather under-represented in modern Chinese folk cultures (see e.g. Amateur musicking in urban Shaanbei; Musicking at the Qing court 1: suite plucking). In Henan the main genre is bantou pieces 板头曲 (pp.724–894), along with their zheng zither repertoire, largely collected around Zhengzhou (cf. The zheng zither in Shandong)—the instrumental component of the dadiao vocal tradition, based on 68-beat variants of the folk melody Baban.

Cao Dongfu.

Despite biographies of the celebrated zheng masters Wang Shengwu (1904–68), Ren Qingzhi (b.1924), Cao Dongfu (1898–1970) and his daughter Cao Guifen (b.1938), one gains little impression of the recent maintenance of this tradition.

Blowing and beating

Without acquaintance of “blowing and beating” (chuida) pieces around the Funiushan and Dabieshan mountains, I’m unclear how they differ in style from the shawm bands discussed above. In Shangcheng county on the northern slopes of Dabieshan, mixed ensembles with strings and percussion (sixian luogu) are found. The famine around 1960 was particularly devastating in the Xinyang region; bands there, derived from shadow puppetry, are said to have “developed” greatly in the 1950s.

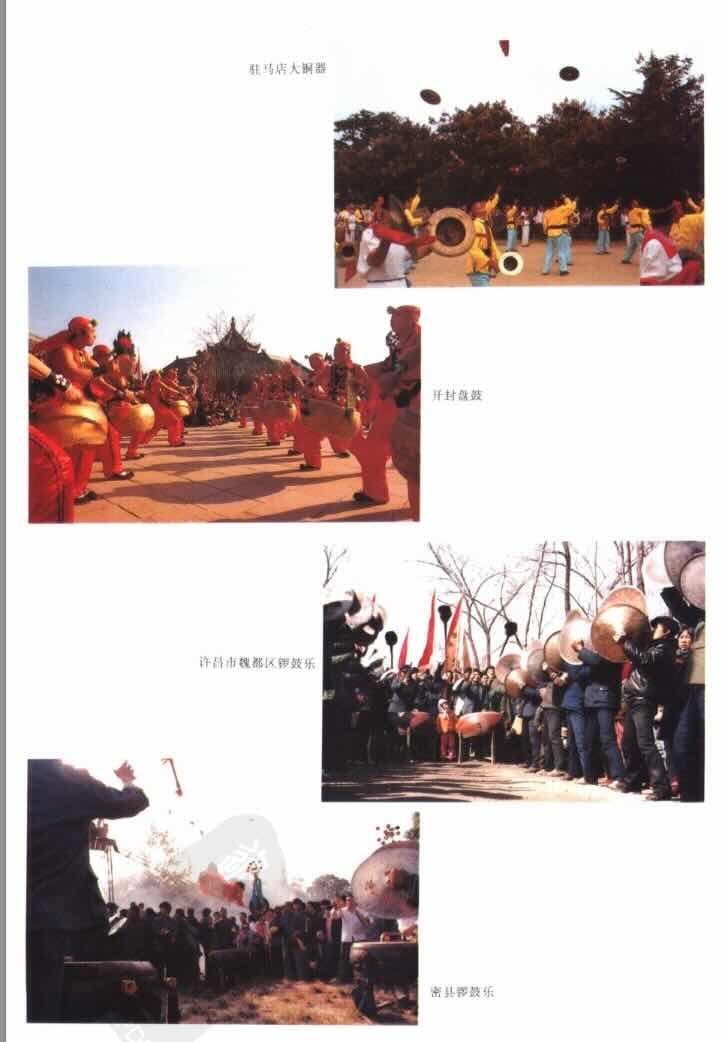

“Greater tongqi“, Zhumadian

Pangu, Kaifeng

Percussion ensemble, Weidu district, Xuchang

Percussion ensemble, Mixian county.

Festive percussion ensembles are introduced in a rather good article (pp.1061–66), including tongqi she 铜 器 社 societies (cf. Xi’an) originally serving temple fairs (with 87 groups active in Xuchang municipality alone at the time of compilation), and the funerary jiagu 架鼓 of Taiqian county, northeast Henan.

More solo pieces are identified than for most other provinces (pp.1197–1334), although most perhaps belong under ensemble and vocal categories: for dizi flute, regional types of bowed fiddles (zhuihu, zhuiqin, sihu, “soft-bow” jinghu), the rare bowed zither yazheng, zheng plucked zither (related to the bantou tradition), and sanxian plucked lute.

“Religious music”

Noting that the very concept of “religious music” is misleading, I often wish that local music collectors would engage with folk ritual practice—and scholars of religion with its soundscape. For regions such as Fujian, on whose local Daoist “altars” scholars have published detailed monographs, little can be learned from the sections on “religious music” in the Anthology; but for regions where serious scholarship is deficient, these sections at least promise some preliminary leads. Despite the long-term social impoverishment of communities in Henan, folk ritual practice there appears to maintain its vigour, yet the minimal Anthology fieldwork yielded disappointing results, and the topic still doesn’t seem to have attracted scholarly attention.

Transcriptions of Buddhist pieces, mostly instrumental, come from Yuanyang, Qixian, Minquan, Zhengyang, and Wuzhi counties, with only two vocal items (from Xinxiang municipality). This section strangely neglects the prominent Xiangguo si temple in Kaifeng, whose “music” was commodified even before the Intangible Cultural Heritage era, although the temple’s Republican-era gongche solfeggio score is reproduced in an Appendix (pp.1441–85). Daoist pieces are transcribed from Yanling, Xunxian, Pingyu, and Huaibin counties; the introduction (p.1378) also mentions a household Daoist group in Gegang district of Qixian county.

[Household?] Buddhist ritual specialists, Xinxiang municipality

Buddhist monks, Lingshan si temple, Luoshan county

Household Daoist presides over funeral, Tongbai county.

Hints of ritual life come in the guise of two brief biographies of wind players who were recognised at regional and provincial festivals in the 1950s:

- Zhang Fusheng 张福生 (Daoist name Yongjing 永净, b.1918) came from a hereditary family of Daoists; he fled the 1942 famine along with his father and seven Daoist priests to make his home at the Guangfu si temple in Yanling county (p.1428).

- Sun Hongde 孙洪德 (Buddhist name Longjiang 隆江, b.1927) came from a poor village in Minquan county; when he was young his mother gave him to the village’s Baiyun si temple, and later he moved with his master Canghai to the Tianxing si temple in Jiangang district of Shangqiu municipality (p.1430).

So far I have found few clues online to augment this paltry material, though a brief 2004 article on “Daoist music” in south Henan (where the officiants are commonly known as daoxian 道仙) is based on fieldwork with six “altars” (tan 坛) there. Further leads welcome!

* * *

A/V recordings of such folk traditions are hard to find online; some brief clips appear on douyin, e.g. “folk ritual from Xinyang” here. Perhaps still more than with local traditions of instrumental music further north and northwest, most of these genres are inseparable from folk-song, narrative-singing, and opera—as a reminder of the importance of vocal music, here’s a clip of “wailing for the soul” (kuling) for the third anniversary of the death:

In the Shaanbei revolutionary base area in the 1930s, cultural cadres struggled to valorise folk performing traditions that were so inextricable from the “feudal superstition” which the CCP was seeking to overthrow (see here). The long process of sanitising such traditions has now reached its nadir in the dumbing-down of the ICH. So, however unsatisfactory, the Anthology remains an essential starting point for fieldwork on local traditions of expressive culture in China, allowing us to adjust our perspective from the “national music” of the conservatoire style, through facile epithets (coined in the 1950s) standing for the music of a large region (Hebei chuige, Jiangnan sizhu, and so on), right down to grassroots fieldwork—town by town, village by village.

While the Henan volumes contain useful material on late imperial and Republican history, what we now need are detailed ethnographies for the whole period since the 1949 “Liberation”, as the social fabric of local communities served by such traditions struggled to survive political and economic assaults.

* For Henan, see e.g. Ralph Thaxton, Catastrophe and contention in rural China (2008), and Peter Seybolt, Throwing the emperor from his horse (1996). For more sources on the famine, see under Cultural revolutions.