NB Other relevant posts can be found in the main Menu

under Gaoluo and Hebei,

where the many fieldnotes (with maps, colour photos, and updates)

are a major addition to material previously published.

Through the 1990s I worked with a fine team of Beijing scholars in a fieldwork project documenting amateur ritual associations on the Hebei plain south of Beijing. This topic has become significant within Chinese musicology, but it belongs within studies of folk religion; our understanding of these organisations has been limited by the fact that they have mainly been cornered by musicologists. In particular, the confusing term yinyuehui (“music association”, see below) has partly disguised their ritual functions, throwing scholars of folk religion off the scent—yet it is they who should be offering insights into the changing ritual life of these villages over the past century.

The ritual association of Qujiaying village, first to be “discovered” in 1986, has been the subject of much publicity—see e.g. my obituary of Lin Zhongshu (and sequel), the village leader who single-handedly, and with extraordinary tenacity, brought Qujiaying to the attention of the outside world, effectively creating the whole topic of Hebei ritual associations. Considerably before the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) project, the Qujiaying association was commodified in a transformation from ritual function to “performances” for visiting bigwigs. But this process has failed to help such amateur ritual organisations weather the challenges of the new capitalism.

On the Hebei plain, most pervasive at village level are hui “associations”. The composite term huidaomen, despite its pejorative use by the CCP, is useful: hui, dao (“Way”), and men (“Gate”). Unlike smaller groups of occupational household ritual specialists elsewhere (such as the Li family Daoists in Shanxi), most such associations are amateur, devotional organisations, often village-wide and ascriptive. They might represent a particular area of the village (as in Gaoluo and Shenshizhuang, and as in towns); and in some villages ascriptive groups overlapped with intra-village, voluntary sectarian groups, as shown by Prasenjit Duara in his study of ritual associations around Beijing, based on Japanese studies from the 1940s—and by our later notes from counties such as Xushui and Xiongxian.

Meanwhile, Chinese musicologists have considered organisations under the headings hui 會, ban 班, and she 社. Ban “bands” are mostly occupational (notably shawm bands guyueban and opera companies xiban); she “societies” are often amateur (such as for narrative-singing), and sometimes religious. While in south China the term tan “altar” is standard for occupational groups of household Daoists, when found in the north it refers to devotional sects, such as the Jiren tan 積仁壇 in East Yuzhuang, Xushui; it also appears in the term kaitan Opening the Altar, and to denote the vocal liturgists (wentan or houtan) of an association.

A most surprising photo: the North Xinzhuang village ritual association posing with their master Daguang, former Buddhist monk , in 1959—of all times…

The Hebei plain was a breeding-ground for so-called “White Lotus” sectarian groups. Hence the reciting of “precious scrolls” (baojuan) in some areas (for a general survey, click here, and for the Yixian–Laishui region, here and here). State attempts to suppress “heterodox” popular religion have a long history. The Ming and Qing codes actually prohibited “associations” (hui); “the Qing code prohibited the formation of associations generally, and specifically banned religious activities involving processions of god images accompanied by music and percussion”. [1] But success in suppression has been chequered, in both imperial and modern times. The White Lotus connection is still evident in the practices and manuals of its ritual associations today, such as around Tianjin (Li Shiyu, Pu Wenqi, Thomas DuBois).

The plain is also a hotbed for underground Catholics, still active after decades of repression (for Gaoluo, see here). As throughout China, spirit mediums practising healing are active too.

Geographical scope

The geographical scope of the project is the Hebei plain south of Beijing nearly as far down to Baoding, in counties as far south as Renqiu, westwards to Yixian, and east to Tianjin and Jinghai—also including the largely rural areas of Beijing and Tianjin municipalities, which share similar same cultural traditions. In Beijing and Tianjin before 1949, ritual practice varied considerably, with élite and popular traditions overlapping. Fieldwork on the Hebei plain incidentally allows us to witness how some of the rituals of imperial Beijing and Tianjin would have been performed, since in urban areas such rituals have become rare.

Trying to define a southern boundary for this type of ritual organization and its attendant performance style, we found this largely amateur tradition of village ritual groups with vocal liturgy and shengguan ensemble, derived from former temple priests or monks. Further south in Hebei (before we reach the Xingtai–Handan regions, where occupational Daoists thrive), religious behaviour still involves many sects, lively temple fairs, mediums, and so on, but religious groups seem to have less connection with liturgy/ritual. Outside this area—north of Beijing, in the Shijiazhuang region and further south, and further west into Shanxi—occupational Daoists, sects, shawm bands, and amateur “performing arts associations” may be active, but we have not heard of amateur village-wide ritual associations. Still, much further fieldwork is needed.

Such devotional ritual groups (whether ascriptive or voluntary) are a significant but sporadic theme elsewhere in China. One thinks of ritual societies around Xi’an, sectarian groups in Jiangsu, dongjing associations in Yunnan, and perhaps the ethnically-mixed groups observing New Year’s rituals in Qinghai and Gansu. Our material doesn’t yet seem to allow us to explain the patchy distribution of such groups.

Ritual associations on the Hebei plain

On the Hebei plain most villages are, or were, represented by a ritual association, whose nominal membership was ascriptive, potentially involving the whole village. They were the most prestigious of local associations, often within the ritual catchment area of a “Great Temple” (dasi) that defined a “parish” (she)—hence the expression “where there is a Great Temple, there is a yinyuehui”. Though we find traces of the parish in many parts of north China, the term “Great Temple” was used most commonly in this part of central Hebei (see Plucking the winds, pp.33–5). On the donors’ lists of some associations we find the term shenshe “holy society”.

These associations are represented by a core group of amateur ritual specialists, who perform for calendrical rituals and funerals (never for weddings), mostly serving the home village. Villages with such an association were thought to be protected by the gods. They acquired their ritual (including vocal liturgy and instrumental ensemble) from Buddhist or Daoist clerics, or from other village associations that had done so, at various stages from the Ming dynasty right until the 1950s. Villagers are well aware of this transmission, referring to their traditions as either “Buddhist monk scriptures” (heshangjing), or “Daoist priest scriptures” (laodaojing); “Daoist transmitted” (daochuan, daomen) or “Buddhist transmitted” (sengchuan, sengmen). The ritual specialists are also sometimes known as laodao, generally a colloquial term in the area for local temple Daoists, as in old Beijing, [2] but here also meaning precisely these people—ordinary lay villagers who have learnt to perform the vocal liturgy and/or the shengguan music. Unlike occupational lay Daoists who have long hereditary traditions and manuals handed down in the family, in this area ritual knowledge is not the monopoly of a particular family, it is not a livelihood (quite the opposite—it detracts from livelihood), and they have little if any formal “Daoist” training apart from learning how to perform the rituals.

The associations are led by one or more huitou “association heads”, known as xiangtou or xiangshou “incense heads” until the 1950s. [3] Leadership and organisational duties are also performed by a small group of senior men called guanshi “organisers”. In imperial times, and even under Maoism, there was a close connection between the “association heads” and the village leadership, with religious and secular power overlapping. But whereas temple committees elsewhere in China are generally organisers rather than ritual specialists, here the core membership also consists of a group of ritual performers (usually around 5 to 10 liturgists and 10 to 30 instrumentalists). Beyond this, the whole village population might be considered to belong to the association by a token donation of tea or cigarettes at the New Year’s rituals. Until the 1950s the associations owned a minimal amount of land. Any male can train to perform the vocal liturgy or instrumental music, with membership not based on lineage, but hereditary transmission is common. They are ordinary peasants, mostly poor, although senior members have a certain prestige.

These associations often have, or had, large collections of ritual paintings such as pantheons and images of individual deities, displayed for rituals. Most common are paintings of the Ten Kings (Shiwang xiang), the Yama Kings of the Ten Palaces (Shidian Yanjun) of the Underworld—a rather close equivalent of European mediaeval depictions of the punishments of hell, and no less graphic. Colorful and stimulating, they make a splash of colour in otherwise drab villages, especially before the advent of TV and horror films. Related images are of Dizang Bodhisattva and the King of Ghosts (Guiwang). Some other main deities of the associations include the Bodhisattva Guanyin and Caishen god of wealth. By the way, the martial god Guandi, so prominent in the wartime material analysed by Duara, now barely features at all.

Pennants and cloth veils also adorn the ritual building. From the late 1980s, as ritual performing traditions atrophied and commercial instincts strengthened, such paintings and hangings, and indeed the scriptures, the soul of the village, were often being sold off to collectors. After all the confiscations and destructions of ritual artefacts over the previous decades, this is very sad, whatever the gains for Chinese black marketeers and foreign collectors. For the New Year rituals, cloth hangings known as beiwen, listing donors to the association, are also displayed at the ritual building—as well as more temporary paper lists (Zhang, Yinyuehui, pp.115–80).

The texts of the vocal liturgy (mainly for funerals) are contained in ritual manuals (jingjuan). We also found many old “precious scrolls” (baojuan), which should also lead us to follow luminaries like Li Shiyu into baojuan studies (note this page, with background here). As in Daoist studies, where the study of ritual manuals predominates over how they are performed, scholars have tended to treat baojuan as silent “books” rather than libretti for performance—but the key is always religious practice in local society.

The vocal liturgists of the association, accompanying themselves on ritual percussion, are known as “civil altar” (wentan; wutan or wuchang may refer either to the shengguan ensemble or to the percussion section). In the western part of the region, some groups consisting only of vocal liturgists were called foshihui “ritual association”.

The paraliturgical shengguan instrumental melodies are also considered “holy pieces” (shenqu) or even “scriptures” (jing).They are notated in scores of gongche solfeggio, containing the melodic outline. Like ritual manuals, gongche scores were handed down from temples. [4]

In sheer volume the Hebei gongche scores are comparable only with those of so-called Xi’an guyue; the latter too is a topic as much for folk religion as for music, but there, scholars collected mainly scores rather than ritual manuals.

On the theme of mobility (including ritual mobility), until younger villagers began boarding packed rickety buses to the towns in search of work in the 1980s, the world of peasants, even in this area near Beijing, was highly circumscribed. Peasants, and ritual specialists, travelled mostly by foot, within a radius of around 20 kilometres. In the 1990s transport problems were to be expected in Shanxi or Shaanxi, but even here, on the plain not far south of Beijing and Tianjin, transport was still far from ideal in the 1990s. Even in the dry northern climate, once we left the main roads, our jeep was often unable to reach villages connected only by narrow rutted tracks.

Terminology

Common terms include “association outing” (chuhui), referring to both calendrical worship and funerals. Whether or not vocal liturgy is performed, terms like “taking out the scriptures” (chujing), “delivering the scriptures” (songjing), or “inviting the scriptures” (qingjing) are often used. The associations perform “seated at the altar” (zuotan). Several terms refer to funeral practice, such as “sending off” (fasong), and (perhaps most frequently heard) “helping out” (laomang), a dialectal expression for the social duty to perform funerals for a bereaved family without any material reward.

Today these associations are commonly known as yinyuehui. Alas, I still regularly find myself having to clarify the specific meanings of the terms yinyue and yinyuehui.

In most villages, the organisation representing the inhabitants had titles like Tea Tent/Great Tent Association (chapenghui, dapenghui) or Lantern Association (denghui), or prefixed by sectarian names like Hunyuan or Hongyang. The Hebei plain was a breeding-ground for so-called “White Lotus” sectarian groups. Hence the reciting of “precious scrolls” (baojuan) in some areas (for a general survey, click here, and for the Yixian–Laishui region, here and here). State attempts to suppress “heterodox” popular religion have a long history. The Ming and Qing codes actually forbade “associations” (hui); “the Qing code prohibited the formation of associations generally, and specifically banned religious activities involving processions of god images accompanied by music and percussion”. [5] But success in suppression has been chequered, in both imperial and modern times. The White Lotus connection is still evident today in the practices and manuals of the ritual associations, such as around Tianjin.

Like ritual specialists throughout north China, most ritual associations in this area have, or should have, three main musical components, chui-da-nian: wind music, percussion music, and vocal liturgy, in reverse order of importance. The “civil altar” performing the vocal liturgy consists of between five and ten performers, accompanying their chanting and singing of the ritual manuals by patterns on ritual percussion instruments including woodblock, a pair of small bells or a small upturned bowl-shaped bell on a stick, a bowl, gong-in-frame, large barrel drum, and small cymbals. Rituals are also punctuated by majestic and solemn percussion patterns led by several pairs of two types of large and heavy cymbals (bo and nao) in dialogue.

The term yinyue denotes the associations’ instrumental “department”, appearing mainly in the title of their gongche scores. Some associations were indeed known as yinyuehui, but for the music scholars who “discovered” them since the 1980s, this has become the overarching term, soon gaining currency through scholarly and media publicity. Throughout north China, villagers use the term yinyue to refer not to any music, but specifically to the paraliturgical shengguan instrumental ensemble music performed as a ritual duty for gods’ days and funerals.

This usage dates back several centuries. The term yinyue is traditionally used thus in Beijing temple Buddhism, and is part of the title of the celebrated 1694 gongche score of the Zhihua temple. The extensive shengguan repertoire transmitted by Buddhist monk Miaoyin in villages of Xiongxian county in the late 18th century, still preserved in several village scores, was an important part of ritual performance there.

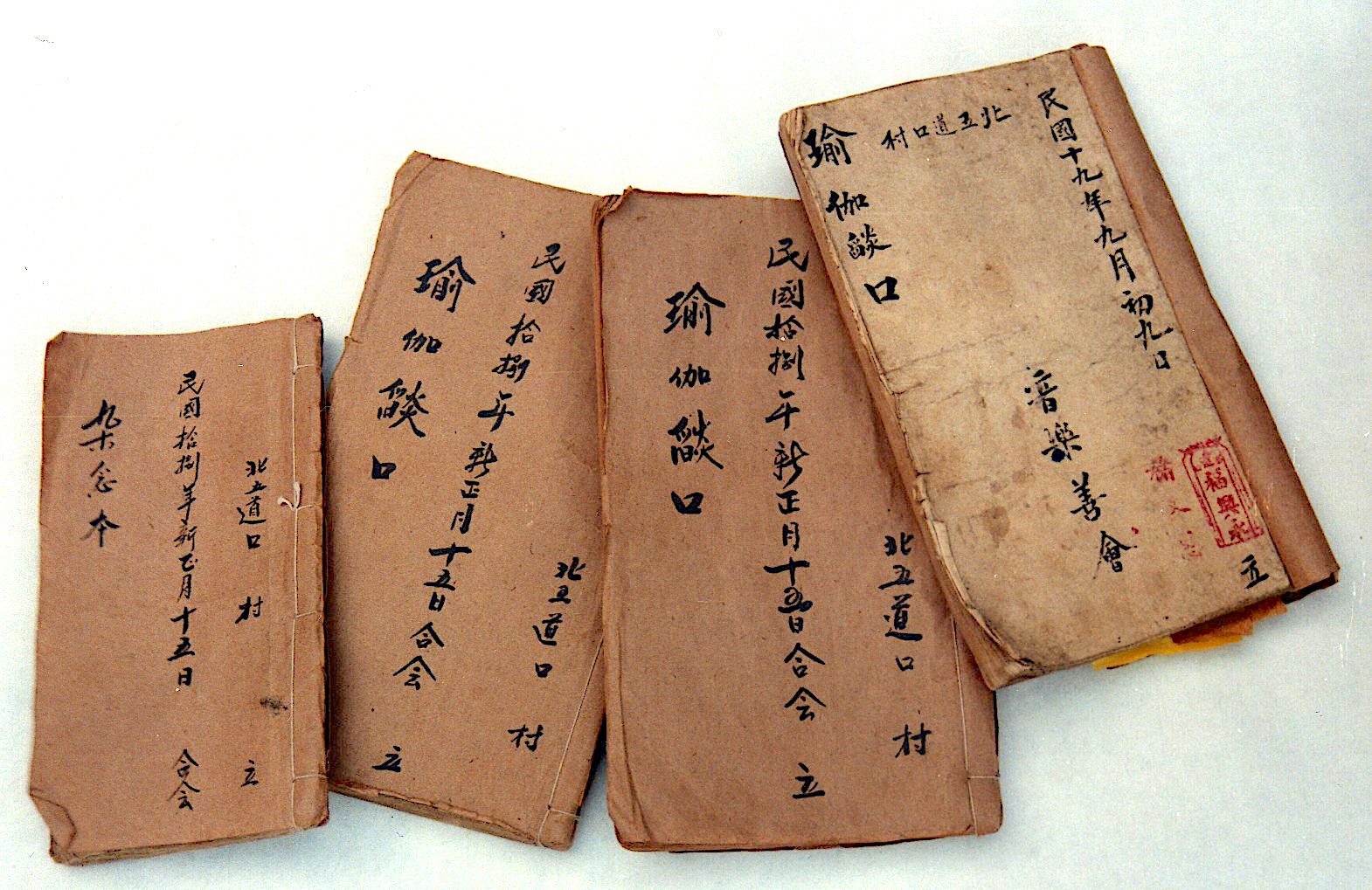

The term yinyuehui appears on pennants, donors’ lists, and the title page of gongche scores, both before and after the 1949 revolution, usually prefixed by the name of the village. such as the 1920 yankou manuals of North Wudaokou (above). More formal terms are yinyue shanhui (shan 善”charitable”, referring to ritual duty), since they exist to “practise good” (xingshan); and yinyue shenghui (sheng “holy” or “illustrious” 聖/盛). Of course, other types of association could also call themselves shanhui or shenghui, as the Miaofengshan material shows.

This technical sense of yinyue is shown in traditional terms like yinyue yankou (yankou with shengguan) and yinyue foshihui (ritual association with shengguan as well as vocal liturgy). Thus while the yinyuehui often subsumes vocal liturgists, the vocal liturgy itself is not properly called yinyue. Nor indeed are other genres of music—neither folk-song nor opera, nor the music of shawm bands. Ironically, of course, the term yinyuehui is the modern name for “concert”—itself a modern concept, one barely known to Hebei peasants until the advent of TV. Thus these are not just “musicians”, and the associations are no more “music societies” than Daoists reciting the scriptures are a book club.

The classic Beijing temple orchestration of the solemn paraliturgical shengguan ensemble music consists of pairs of the four types of melodic instruments (sheng-guan-di-luo); although in numbers village ritual groups tend to be much larger than occupational household groups of ritual specialists, often consisting of over twenty musicians, in their instrumentation they are more “classical” than those we found in Shanxi and further west, with the yunluo here always a frame of ten gongs, and without small suona shawm or bowed fiddle. This ensemble music (yinyue!) is as much a part of ritual observance as is vocal liturgy. It would be quite wrong to consider these associations as “musical”, with our baggage of secular modern meanings.

Even Gaoluo’s 1980 gongche score is entitled Nandeng hui (Southern Lantern Association), not yinyuehui! The common terms for the Gaoluo groups were Lantern association (denghui), Blue Banner Holy Association (Lanqi shenghui), and Guanyin Hall (Guanyin tang).

Ritual duties

The associations are responsible for leading the calendrical rituals of their home village—not, in this area, a very dense annual list, even before Communism. As elsewhere in north China, village temples went into a long decline from the beginning of the 20th century, intensifying under Maoism; temples staffed by resident priests have long been rare except in some larger cities. Though both the music and ritual of the associations were associated with Buddhist and Daoists clerics, in this area there have been few full-time priests since the 1950s, and even occupational groups of household Daoists are rare: thus the amateur practitioners of the ritual associations became the main public intermediaries with the divine world.

In this region, though most associations once served a village temple, fewer temples have been rebuilt since the 1980s’ reforms than in many parts of north and south China.Thus in many villages by the 1960s the only functioning public religious site was the building of the ritual association, called “public (or official) building” (guanfangzi—Zhang, Yinyuehui, pp.181–204), or a specially erected tent (peng, commonly “lantern tent” dengpeng), or even the brigade office, adorned with god paintings almost solely for the New Year rituals.

There are still a few major temple fairs, like those of Houshan and Maozhou, which attract visitors from a wide area, and thus involve significant accommodation with the local state; but the calendrical rituals of most vlllages are local and small-scale. The main event of the annual calendar is the New Year lantern rituals around 1st moon 15th, with the altar opened (kaitan) around the 12th, and the gods escorted away around the 17th. But enduring evidence of a more busy former festive life based on temples and worship can still be found in temple fairs such as those for Houtu (3rd moon) and the Medicine King (4th moon 18th, e.g. Kaikou in Xiongxian). The 7th-moon Ghost festival (Releasing the Lanterns fangdeng), notable around the Baiyangdian lake and around Langfang, does not revolve around a temple. Village associations sometimes pay respects at each other’s temple fairs, but such networks are not extensive or formal.

We can identify broad cult areas, like the Medicine King (Yaowang) cult around Maozhou in the south of our area, but associations identifying themselves as serving a particular deity were quite rare. Until the 1950s, many village associations in the Yixian–Laishui–Dingxing–Xushui area made pilgrimages to the Houshan mountain temple complex in the 3rd moon for the cult of the female deity Houtu, and many still observe the festival in their home village; some had Houtu paintings, and some recited the Houtu precious scroll, but even these groups didn’t formally identify themselves as Houtu associations. So the main activity is performing for funerals, and since they mainly serve within the village as a social duty, even this does not demand much of their time.

These ritual associations can’t be bracketed along with the “performing arts associations” (huahui). They too may perform for calendrical rituals, such as yangge dance troupes until the 1950s, but they are voluntary, less inclusive groups. Conversely, the ritual associations perform religious duties as intermediaries with the gods on behalf of the whole village, embracing both sacred and secular realms. However, the sectarian groups described by DuBois in the southeast of our area are very much part of the same phenomenon—ritual specialists performing as a charitable duty, often representing the whole village.

Ethnomusicology seeks to place soundscape in social context, but for this topic, apart from the writings of Zhang Zhentao, the results have been partial. An instance of a fruitful way of looking at the Hebei phenomenon is Prasenjit Duara, Culture, power, and the state: rural north China, 1900-1942 (1988; Chinese edition here, valuable material for my Chinese colleagues). He studies the “cultural nexus of power” in the Republican era, based on Japanese surveys during the occupation—a small but detailed sample of six villages from a rather wide area surrounding Beijing. Revealing the importance of popular religion, in Chapter 5 he defines four categories:

1 village-bound, voluntary

2 Super-village, voluntary

3 *Village-wide, ascriptive*

4 Combined: supra-village, yet involving the whole village (often for self-defence).

Most of the groups we studied seem best to fit Duara’s type 3—“religious organisations that were the only village-wide organisations, […] the agencies that responded to the collective needs of the village”, with their tutelary deities, pantheons, and gods of the underworld. Note again that while all villagers may nominally belong to the association, a core group of ritual specialists represents them in communicating with the gods. [7]

Duara shows that the intrusion of the state into local society dates back well before the Communist era:

The growth of the state transformed and delegitimised the traditional cultural nexus during the Republican era, particularly in the realm of village leadership and finances. Thus, the expansion of state power was ultimately and paradoxically responsible for the revolution in China as it eroded the foundations of village life, leaving nothing in its place.

For funerals, the ritual specialists of many village associations could stage a quite elaborate series of rituals for the salvation of the soul, that one associates with occupational ritual specialists—such as Crossing the Bridges (duqiao), Smashing the Hells (poyu), and yankou. Indeed, some groups dress in Buddhist or Daoist robes to perform the vocal liturgy. They sing hymns from memory, but recite the lengthy “precious scrolls” with the aid of the volume set before them.

Apart from their main duties within the home village, the association ritual specialists sometimes accept invitations to perform funerals in neighbouring villages, over a small radius of around 15 kilometres. At such times they are more like a group of voluntary amateur ritual specialists, but usually, when performing in their home village, they serve an ascriptive membership.

Within this large area, I suggest some local variations. Though our survey could never be adequate, it reminds us again of the need for detailed fieldwork. Just southeast of Beijing, the largely occupational groups have strong ritual traditions acquired from temple clerics only in the 1950s. Around Bazhou, traditions are amateur, often with clear links to Daoist priests. Around Yixian, the associations are again amateur, and early; the cult of Houtu is a major factor in ritual activity, and the area is distinguished partly by the additional occurrence of groups reciting vocal liturgy with percussion alone, including “precious scrolls” derived from White Lotus sects.

But the three main temple transmissions that I highlight in these areas were only part of ritual elements there, chosen because we happen to have rather detailed material. My point is not so much to show transmission from a particular temple, but to illustrate that the network of village ritual specialists who acquired their practices from Daoist and Buddhist clerics stretched back into imperial times.

Social and ritual change

Whereas smaller occupational groups of household Daoists learn the complete repertoire including both vocal liturgy and shengguan, in these larger amateur groups there is a clear division of labour between the small group of liturgists and the often large group of shengguan instrumentalists. Some associations that originally had only vocal liturgy decided they needed shengguan music too. Some that used to have both vocal liturgy and shengguan music now have only one of these elements—we may assume that most yinyuehui performed vocal liturgy before 1937, for instance.

In many associations the list of rituals has been abbreviated since the 1950s, as an indirect result of political pressures; the complex shengguan instrumental music has remained an intrinsic feature of these rituals even when vocal liturgy has fallen out of use. For the voluntary sectarian groups and the foshihui, vocal liturgy was primary. Most of the village-wide ascriptive associations used yinyue melodic instrumental ensemble music in addition to vocal liturgy—as did some voluntary sectarian groups like the Tiandimen in Jinghai. Some counties now have little vocal liturgy—like Xiongxian, with its fine shengguan groups and early gongche scores. Some counties didn’t have many groups at all, such as Gu’an and Zhuozhou.

However, by the mid-1990s, several associations that had survived barely since the 1950s by performing only their instrumental music for rituals were keen to relearn their vocal liturgy. The musically outstanding Gaoqiao village association started playing their shengguan music for rituals again in 1979, but only resumed scripture recitation in 1992.

Apart from the solemn and conservative ritual shengguan instrumental music (also known as beiyue “northern music”, or xiaoguan “small guanzi”), since early in the 20th century some village associations converted to a style called “southern music” (nanyue, or daguan “large guanzi”), led by a larger guanzi oboe and also using a small shawm and a bowed fiddle, playing more popular pieces related to folk-song and opera. This style was also transmitted by monks and priests before Liberation, like the monk Haibo around Laishui, and the priest Yang Yuanheng (1894–1959) from the Lüzu tang temple in Anping county; [8] and most groups remained amateur, serving the same types of rituals as the yinyuehui from which they evolved.

Village associations have loose personal and customary ties of cooperation, based on earlier transmission and geography. [9] Villagers are aware of other associations in their area; they can tell you which nearby villages have a yinyuehui, a nanyuehui, or a foshihui, and which are “Buddhist” or “Daoist” scriptures, or have “only” a martial-arts or a lion-dancing group. But such local knowledge does not, at least not any longer, amount to an active network of support, far from the fenxiang “division of incense” networks of the southeast.

Occupational groups like household Daoists appear to be weathering the new capitalist ethos quite well. So too do the more devotional amateur groups like sects and Catholics, with their frequent and inclusive rituals. But while many of the amateur associations also staged an impressive revival through the 1980s, migration, modern popular culture, and mercenary values took a toll (see my “Revival in crisis”). The associations have entered a new phase since being taken up by the ICH project, which has moulded them to secular official goals while giving some a new lease of life—yet the basic issues remain unresolved.

A note on sources

Our team consisted mainly of Xue Yibing, Zhang Zhentao, Qiao Jianzhong, and me. Attempting to survey a region comprising over a dozen counties, we collected data (fieldnotes, photos, copies of ritual manuals and gongche scores, audio and video recordings) on over a hundred villages. Since we could not always coincide with a ritual (which in this area are anyway quite sporadic), we sometimes had to fall back on requesting them to perform for us. (Contrast Yanggao in Shanxi, where no more than a couple of days ever seem to pass without the Daoists and shawm bands going out to do rituals!). As not all of the associations were currently active, some of our visits consisted of brief interviews.

Our main notes (mostly by Xue Yibing and Zhang Zhentao) are from 1993 to 1996 (as well as some by Wang Shenshen, Han Mei, and Du Yaxiong, to whom I am also grateful), but come also from our many fieldwork trips from 1986 through 2003. Early fieldwork in Hebei for the Anthology on “religious music” is disappointing (see In search of the folk Daoists, pp.128–9).

Undigested notes from fifty of the villages were printed in Zhongguo yinyue nianjian 中国音乐年鉴 1994–96. In English, I surveyed the groups in Chapter 11 of Folk music of China, and (with Xue Yibing) “The music associations of Hebei province, China: a preliminary report”, Ethnomusicology 35.1 (1991).

I reflected further on the associations in “Chinese ritual music under Mao and Deng”, British Journal of Ethnomusicology 8 (1999), but eventually focused on a historical ethnography of one village, Gaoluo (Plucking the Winds, 2004). See also my “Revival in crisis: amateur ritual associations in Hebei”, in Adam Chau ed., Religious revitalization and innovation in contemporary China (Routledge, 2010).

Among a proliferation of publications in Chinese, note two fine studies by Zhang Zhentao 張振涛,

- Yinyuehui: Jizhong xiangcun lisuzhongde guchuiyueshe 音乐会: 冀中乡村礼俗中的鼓吹乐社 (2002)

- Jizhong xue’an: yinyue feiwuzhi wenhua yichan wenji 冀中学案—音乐类非物质文化遗产文集 (2020, 2 vols).

A major recent project, led by Qi Yi 齐易, is revisiting many of these groups and finding yet more. You can find videos and fieldnotes on Qi Yi’s Wechat public account, as well as searching under 土地与歌 or specific place-names. Narrowly focused on “music, it suffers from the reifying approach of the ICH, with ia large team and formal approach. For music scholars (and indeed for villagers keen to learn the instrumental repertoire), most valuable sections of this project show the gongche solfeggio of the score while masters recite them, such as this from Hanzhuang, Xiongxian (cf. my Gaoluo film, from 5.43). The project also records other performing genres such as the huahui and local opera troupes.

A major recent project, led by Qi Yi 齐易, is revisiting many of these groups and finding yet more. You can find videos and fieldnotes on Qi Yi’s Wechat public account, as well as searching under 土地与歌 or specific place-names. Narrowly focused on “music, it suffers from the reifying approach of the ICH, with ia large team and formal approach. For music scholars (and indeed for villagers keen to learn the instrumental repertoire), most valuable sections of this project show the gongche solfeggio of the score while masters recite them, such as this from Hanzhuang, Xiongxian (cf. my Gaoluo film, from 5.43). The project also records other performing genres such as the huahui and local opera troupes.

For the broader sociological picture, see also the Japanese surveys from 1940 to 1942 cited by Duara, for a handful of villages just around the margin of this area; and Gamble 1954 and 1963 for Dingxian just south. In Chinese religious studies, there is much research on early textual evidence for groups considered part of “White Lotus” sectarian religion (Naquin, Overmyer, Ter Haar), but few first-hand studies apart from the outstanding fieldwork of Li Shiyu, Pu Wenqi, and Thomas DuBois. For the Baoding region, cf. Daniel L. Overmyer [Ou Danian] and Fan Lizhu (eds) (2006–7) Huabei nongcun minjian wenhua yanjiu congshu [Studies of the popular culture of north China villages] (4 vols, Tianjin guji chubanshe), consisting of articles on the Baoding region, Xianghe and Gu’an counties, as well as Handan region of south Hebei.

Once again, while soundscape is always important in ritual studies, I have to stress that this topic belongs to the wider realm of studies of folk religion, beyond the echelons of musicology.

This page is revised from the Introduction to Part Three of my 2010 book In search of the folk Daoists of north China; for full citations, see Bibliography there. Fieldnotes from several areas of the Hebei plain are featured in a series of posts in the main Menu under Hebei.

[1] Naquin 1992, pp.351–2; cf. Esherick, The origins of the Boxer uprising, pp.41–2.

[2] Goossaert, The Taoists of Peking, p.83, cf. Appendix 1 of In search of the folk Daoists.

[3] Note that this is the common meaning of xiangtou in this area—unlike in Cangzhou to the southeast (Dubois, The sacred village, pp.65–85), or around Beijing in the 1940s (Li Wei-tsu, “On the cult of the four sacred animals”, a classic source from 1948), where it denotes spirit mediums. However, the term “incense association” (xianghui) seems less common on the Hebei plain.

[4] On gongche scores, see Zhang Zhentao, Yinyuehui, pp.367–407, and the Hebei volumes of the major anthology Zhongguo gongchepu jicheng 中国工尺谱集成.

[5] Naquin, cited in Jones, In search of the folk Daoists, pp.125–7.

[7] Cf. Liu Tieliang, “Cunluo miaohuide chuantong jiqi tiaozheng”, pp.269–80, for temple fairs. Duara’s classification is sometimes ambiguous. In his first category he includes “lantern associations” denghui, which in Gaoluo indicates the ascriptive groups representing the ritual needs of the village (now known as yinyuehui).

[8] For Haibo, see Plucking the winds, p.71, cf. In search of the folk Daoists §9.7; for Yang Yuanheng, later professor of guanzi at the Central Conservatoire in Beijing, see my Folk music of China, p.197.

[9] Cf. Dubois, The sacred village, p.160.