In articles on this site I often stress how soundscape is basic to ritual performance. In north China ritual specialists identify three types of organized ritual sound, “blowing, beating, and reciting” (chuidanian): melodic instrumental music, percussion, and vocal liturgy—in reverse order of importance, with vocal liturgy primary. Some groups accompany their vocal liturgy only with percussion, but where melodic instrumental music is performed, it is an essential component of ritual: “holy pieces” (shenqu), transcending language. Whereas vocal liturgy is not notated—most ritual manuals document only the texts, not the melodies to which they are sung—the outline of the melodic (and indeed percussion) instrumental music that punctuates and accompanies it is recorded in scores of gongche solfeggio. [1]

When the Qujiaying village ritual association, south of Beijing, was “discovered” in 1986 we already knew about the shengguan ensemble and its gongche scores (notably those of the Zhihua temple in Beijing) thanks to the ground-breaking work on Yang Yinliu in the early 1950s, later comprehensively studied by Yuan Jingfang. In our project on the Hebei plain, we soon broadened our attention to ritual manuals, but the shengguan wind ensemble and the scores of village ritual associations were always among our major concerns.

In the fine tradition of anthologies that Chinese musicologists do so well, the major new compendium

- Zhongguo gongchepu jicheng 中国工尺谱集成 [1]

collects some of the most important scores of gongche solfeggio. It provides rich material on the continuity of early history with modern folk practice.

The anthology is based more on northern shengguan than on southern genres—the distinctive scores of nanyin in Fujian and Taiwan are already collected in many separate anthologies.

The compendium comprises ten volumes to date:

- General (a fine introduction to historical variants of notation and metrical markers)

- Beijing (2 vols)

- Hebei (3 vols)

- Shaanxi (2 vols, for the major repertoires of ritual groups around Xi’an)

- Jiangsu (including major early Daoist scores)

- Liaoning (including scores for both shengguan and the amazing shawm bands there)

The scores of Beijing temples, and those of the related village ritual associations on the Hebei plain just south, take pride of place. The detailed commentaries on the Hebei and Beijing material are the work of Zhang Zhentao, continuing the masterly chapter in his book Yinyuehui.

Most volumes further include useful tables of qupai labelled melodies.

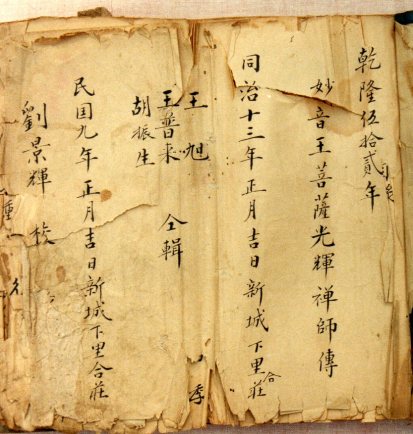

Such scores also often contain precious prefaces bearing dates of transmission, as we saw in Xiongxian.

* * *

Of course, like the Daoist Canon, and like the ritual manuals of living groups, scores are merely silent artefacts. They should be combined with recordings of their transmitters, who have long experience of bringing them to life—first by decorating the skeletal notes of the score by singing in unison, and then in ritual performance, taking the instruments up to play them in heterophony suitable to the different instrument types. While some musicians learn mainly by ear, the score is an important repository representing the tradition.

But just in case you think the silent score is somehow equivalent to “the music”, then don’t just consult my transcription of Hesi pai under West An’gezhuang here (§2), but listen to the shengguan tracks on the playlist in the sidebar (including tracks 9 and 10, showing the progressive decorations)!

I should also add that notation is not a criterion for excellence. Many musicians, and ritual specialists, in the great and small traditions of the world don’t need it at all, and for others it is merely an aide-memoire, as in this case.

Indeed, this isn’t just an issue for music. This is not the place to discuss wider issues of oral and literate cultures, but this radical comment from Plato, no less, is suggestive:

This discovery of yours [writing] will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things but will remember nothing; they will appear to be omniscient but will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.

As Paul Cooper comments,

I love that when Plato complains about the spread of the written word in 370 BC, he sounds like my granddad complaining about the internet.

Such issues are thoughtfully explored by ethnomusicologists—for leads, see the fine chapters of Ter Ellingson and Richard Widdess in Ethnomusicology: an introduction (The New Grove handbooks in music), and Bruno Nettl, The study of Ethnomusicology: thirty-three discussions, chs. 20 and 26. And for wise words on the history of notation in WAM, see here.

These gongche scores are a major aspect of the study of ritual. But that’s enough writing—wouldn’t want to offend Plato…

[1] See e.g. http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2017-09/06/c_129697492.htm,

http://3g.china.com/act/culture/11171062/20170906/31301663.html,

http://news.takungpao.com/mainland/topnews/2017-09/3491181.html.

[2] I gave an overview of gongche notation in my Folk music of China (ch.7); cf. my article “Source and stream: early music and living traditions in China”, Early Music August 1996, pp.375–88. As ever, Yang Yinliu gave a masterly survey in his Gongchepu qianshuo 工尺谱浅说 (1962).

Pingback: A tribute to Li Wenru | Stephen Jones: a blog

So will these volumes display Gongche notation as well as a realisation in either jianpu/western notation?

LikeLike

Ha, no, but good point. Just added a bit about decoration and sound. Transnotating the bare skeletal gongche would only be a start. More to the point would be to have more published recordings!

LikeLike

Pingback: At home with a master Daoist | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Zhihua temple group in London! | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Solfeggio | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Three baldies and a mouth-organ | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Indian singing at the BM | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Chet in Italy | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Musicking | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Yanggao personalities | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Recopying ritual manuals | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Musicking at the Qing court 1: suite plucking | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Amateur musicking in urban Shaanbei | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A tribute to Yang Yinliu | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Images from the Maoist era | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A Daoist ritual, Suzhou 1956 | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Buddhism under Mao: Wutaishan | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Unpacking “improvisation” | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Dream songs | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Transmission and change: Noh drama | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The genius of Abbey road | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Ritual artisans in 1950s’ Beijing | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Bruce Jackson on fieldwork | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Labrang 1: representing Tibetan ritual culture | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A Beatles roundup | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Killer sounds: cadential patterns in Chinese melody – Dinesh Chandra China Story