In my post on Frank Morgan I mentioned how he managed to keep active on sax while in San Quentin by playing along with fellow inmates.

That post set forth from LA detective Harry Bosch’s good taste in jazz, and again Michael Connelly’s novels have some pertinent comments on Art Pepper (1925–82), who was one of Morgan’s jazz colleagues in jail.

Pepper was no angel either. Like Chet Baker, he was a white West-coast junkie. In Connelly’s A darkness more than night (2000) he evokes the classic 1957 album Art Pepper meets the rhythm section:

He went into the house and got two more beers out of the refrigerator. This time McCaleb was standing in the living room when he came back from the kitchen. He handed Bosch his empty bottle and Bosch wondered for a moment if he had finished it or poured the beer over the side of the deck. He took the empty into the kitchen and when he came back McCaleb was standing at the stereo studying a CD case.

“This what’s playing?” he asked. Art Pepper meets the rhythm section?”

Bosch stepped over.

“Yeah. Art Pepper and Miles’s side men. Red Garland on piano, Pau Chambers on bass, Philly Joe Jones on drums. Recorded here in LA, January 19, 1957. One day. The cork in the neck of Pepper’s sax was supposedly cracked but it didn’t matter. He had one shot with those guys. He made the most of it. One day, one shot, one classic. That’s the way to do it.”

“These guys were in Miles Davis’s band?”

“At the time.”

McCaleb nodded. Bosch leaned close to look at the CD cover in McCaleb’s hands.

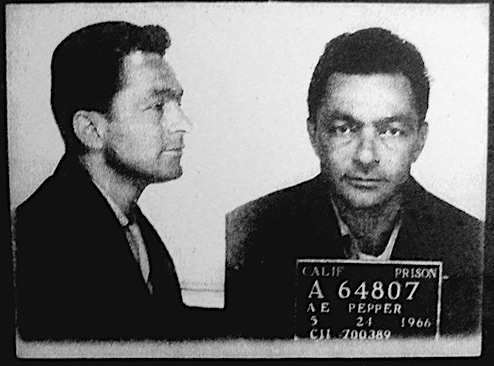

“Yeah, Art Pepper,” he said. “When I was growing up I never knew who my father was. My mother, she used to have a lot of this guy’s records. She hung out at some of the jazz clubs where he’d play. Handsome devil, Art was. For a hype. Just look at that picture. Too cool to fool. I made up this whole story about how he was my old man and he wasn’t around ’cause he was always on the road and making records. Almost got to the point I believed it. Later on—I mean years later—I read a book about him. It said he was junk sick when they took that picture. He puked as soon as it was over and went back to bed.”

McCaleb studied the photograph on the CD. A handsome man leaning against a tree, his sax cradled in his right arm.

“Well, he could play,” McCaleb said.

“Yeah, he could,” Bosch agreed. “Genius with a needle in his arm.”

Bosch stepped over and turned the volume up slightly. The song was Straight life, Pepper’s signature composition.

“Do you believe that?” McCaleb asked.

“What, that he was a genius? Yeah, he was with the sax.”

“No, I mean do you think that every genius—musician, artist, even a detective—has a fatal flaw like that? The needle in the arm.”

“I think everybody’s got a fatal flaw, whether they’re a genius or not.”

The full album seems to have disappeared from YouTube, so here’s Straight life:

The song Patricia features in The black box (2012):

Bosch had begun making his way through the Art Pepper recordings his daughter had given him for his birthday. He was on volume 3 and listening to a stunning version of Patricia recorded three decades earlier at a club in Croydon, England. It was during Pepper’s comeback period after the years of drug addiction and incarceration. On this night in 1981 he had everything working. On this one song, Bosch believed he was proving that no-one would ever play better. Harry wasn’t exactly sure what the word ethereal meant, but it was the word that came to mind. The song was perfect, the saxophone was perfect, the interplay and communication between Pepper and his three band mates was as perfect and orchestrated as the movement of four fingers on a hand. There were a lot of words used to describe jazz music. Bosch had read them over the years in the magazines and in the liner notes of records. He didn’t always understand them. He just knew what he liked, and this was it. Powerful and relentless, and sometimes sad.

He found it hard to concentrate on the computer screen as the song played, the band going on almost twenty minutes with it. He had Patricia on other records and CDs. It was one of Pepper’s signatures. But he had never heard it played with such sinewy passion. He looked at his daughter, who was lying on the couch reading a book. Another school assignment. This one was called The fault in our stars.

“This is about his daughter,” he said

Maddie looked over the book at him.

“What do you mean?”

“This song. Patricia. He wrote it for his daughter. He was away from her for long periods in her life, but he loved her and he missed her. You can hear that in it, right?”

She thought a moment and then nodded.

“I think. It almost sounds like the saxophone is crying.”

Like Frank Morgan, Art Pepper rebuilt his career after being freed from prison in 1965. Here’s a 1978 recording of Patricia:

Don McGlynn’s documentary Art Pepper: notes from a jazz survivor, filmed in 1982, his last year, also features his third wife Laurie (with Patricia discussed from 24.00):

In the LRB Terry Castle riffs brilliantly on Pepper’s 1979 autobiography Straight life.

Aside from “the music itself” (sic), while accounts of jazzers’ lives are vivid (e.g. Miles, Mingus, Chet…), it’s possible to tire of them: self-destruction is one thing, but the misogyny is hard to take. As with WAM composers, we may learn from their stories and the society in which they lived, but admiring the music doesn’t have to entail endorsing its creators. Men behaving badly yet again… (cf. Deviating from behavioural norms).