The elephant in the room

or

The ivory tower

Today we take for granted the colour scheme of the piano keys, with white “natural” notes and black “chromatics” . But the layout was only standardised after around 1810; on most early harpsichords, fortepianos, and organs, the colours are reversed. [1]

Left: harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers (Antwerp, 1646),

remodelled and expanded by Pascal Taskin (Paris, 1780).

Right: fortepiano by Johann Andreas Stein (Augsburg, 1775).

Source: wiki.

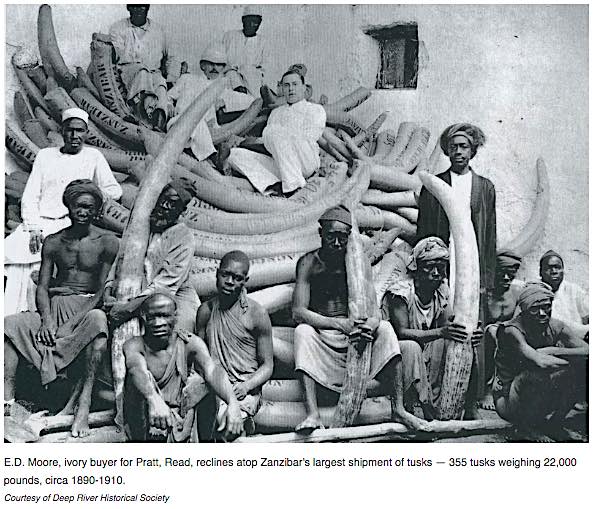

Historians are showing ever more clearly how the prosperity of Western imperial nations was built upon slavery (e.g. here; see also the note in Hidden heritage). And as ivory became a prized symbol of affluence,

with the establishment of the early-modern slave trades from East and West Africa, freshly captured slaves were used to carry the heavy tusks to the ports where both the tusks and their carriers were sold.

Meanwhile, worthy efforts are being made to write black composers and performers into the story of Western Art Music (WAM). However, such discussion as I’ve found of the reversal of the keyboard’s colours comes from within the rarefied echelons of musicology—still largely a bastion of “autonomous music” divorced from society (with some honourable exceptions, under Society and soundscape; note also recent initiatives such as this). So even those who take note of the colour reversal (e.g. here, and this) suggest innocent explanations, ignoring the elephant in the room. It’s not exactly a conspiracy of silence, just a scene dominated by white people in their ivory tower. While I can’t see the wider picture here, I’d be intrigued to see what historians of colonialism and the global slave trade might make of this.

Within WAM, some ingenuous commentators seek to explain the change by the practical reason of visual clarity: supposedly, when the adjacent (“natural”) keys were black, they were hard to distinguish since the space between them was also dark, so the new scheme made them easier to identify. Implausibly, this seems to suggest that master performers like Bach and Mozart just couldn’t help playing fistfuls of wrong notes, and that modern players of historical instruments rashly run the same risk.[2]

Mozart’s piano, by Anton Walter—played in our times by the brilliant Robert Levin

e.g. here. [3]

Surely such an explanation falls between the cracks. While keyboards with white naturals and black chromatics were quite common (such as those depicted by Vermeer), [4] the reverse system was well-established and long-lived—anything but a fleeting experiment before makers “got it right”. This more common early layout seems to make economic sense: the “natural” keys were larger, longer, and more numerous; black keys were made of ebony (promising article here) or rosewood, while white keys were covered with ivory, which was more scarce and more costly.

But after a couple of centuries of colour diversity, the scheme of white naturals and black chromatics became standardised from the early 19th century, and this coincided with several factors that I have yet to see spelled out. As importing ivory became more efficient (I surmise) it must have become rather less expensive (cf. fluctuating costs of ebony manufacture?); and as industrial production developed, the piano market surged—notably among the social classes making lucrative profits from slavery and the ivory trade. So we might want to find out how piano prices and incomes changed over the period, for German, French, Dutch, and English producers and consumers.

An article on one corner of American piano manufacture since the mid-19th century suggests the kind of approach I’m seeking.

It may be hard to find out how white supremacy came to be inlaid onto the piano keyboard within a couple of decades early in the 19th century. Doubtless both aesthetic and socio-economic factors played a role; but it’s an interesting coincidence that the change occurred just as profits from the trade in ivory and slaves were soaring. So I hope this post will read not so much as a Guardian-reading tofu-eating wokerati rant but as a plea for broader-based and informed research (cf. Empireland).

* * *

Returning to more purely aesthetic concerns, a friend also wonders if a predominantly white keyboard was considered more pleasing in salons and concert halls where musicians wore dark suits and audiences sat at a distance. Another, later story (that, mercifully, I won’t attempt to cover) is the overall contours of the instrument’s body: how the varied shades of elegantly decorated wood yielded to the modern concert grand—massive, impersonal, shiny, and black (white instruments appealing mainly to the tastes of such as R. Clayderman and D. Trump).

It’s hard to gauge if playing on one or the other keyboard had, or has, any effect on performers or audiences—for instance, if modern players who use both early and later models are influenced in some obscure way by playing on instruments of one or the other type.

As a relief from such meretricious speculation, let’s rejoice in one of the funkiest keyboard solos ever:

You will note that this colourised version of The chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (featured in my post on Susan McClary’s stimulating political analysis of the cadenza) shows Gustav Leonhardt apparently playing a harpsichord with white natural keys and black chromatics—as is a 1640 instrument by Johannes Ruckers in Antwerp played by Richard Egarr, seen and heard in the same post. Tickling the ivories was never an entirely black and white issue…

Let’s play out with Hazel Scott (in The heat is on, 1943)—the piano on the left presumably a novelty one-off, specially manufactured:

[1] Wiki articles on Harpsichord, Piano, Fortepiano, and Musical keyboard make useful introductions. BTW, in the Sachs-Hornbostel taxonomy of instruments the piano is classified as a subdivision of §31, alongside musical bows and zithers.

[2] What about blind players, one might ask? An even more dodgy claim is that “the custom of having the naturals a darker colour was said to have originated in France to show off the player’s hands to better advantage”.

[2] What about blind players, one might ask? An even more dodgy claim is that “the custom of having the naturals a darker colour was said to have originated in France to show off the player’s hands to better advantage”.

Left: Frances Cole (1937–83).

Another aside: although the old theory that Beethoven was black sometimes gets exhumed on social media (and is soon reburied), it can still lead to interesting conversations, like this.

[3] More Mozart pianos concertos here. For the different timbres of early pianos—even up to the 1950s—see my note here on Beethoven’s wondrous Op. 109 sonata. For a modern performance of Brahms on a piano of his time, click here. In my tribute to Fou Ts’ong I refer to Richard Kraus’s fine study of pianos and politics in China.

[4] So was this layout, which only achieved a monopoly considerably later, more common in the Netherlands—and if so, might that be because since the Dutch empire prospered earlier than its rivals, its keyboard makers had earlier access to ivory? Maybe someone can direct me to a large image database for early keyboards.

Simon Mills, erudite authority on Korean musical cultures, writes:

Thanks for this fascinating post, Steve! Like many other people, I haven’t properly considered before why that black/white switch around took place. Here are some of my own musings on the matter…

My first thought is that it was probably due to a combination of factors. I think the visibility-of-gaps-between-keys theory holds up very well as one of them. Yes, excellent players wouldn’t have needed that, but most players would not have been especially skilled, and perhaps the switching is partly indicative of the fact that playing was becoming less of a specialist pursuit?

Then material availability would have been another factor (as suggested) – with ivory becoming easier to obtain yet remaining somewhat special (so a gleaming display of it would have served well as minor ostentation). Material durability and workability may also have been factors: perhaps the craftsmen developed new skills and technology for working effectively with ivory, while considering it suitably durable and especially good-to-the-touch for players?

Then there’s the aesthetics of it: fashions change, also regarding colours, negatives and their combinations. Perhaps having more white “worked better” in relation to the other colours, shades and qualities of light favoured in rooms during that period? Maybe the white stood out more strongly in those environments – or possibly the reverse, if that’s what they were after?

Finally, I think there’s a kind of satisfying symbolic logic to the white/black system too: people might well have equated white with purity and simplicity (C major) and black with darkness and complexity (chromaticism) – though I guess that associations of white/black with skin hue would have played a minor role in the symbolic understanding because those were very different times regarding race demographics, relations, and consciousness.

Regarding that symbolic dimension, I’m reminded of some interviews that my partner and I conducted a few years ago. The first was with a Korean woman who had grown up in a very remote Korean village. At one point, she recalled the first time she saw a piano at the age of 15, and described the keyboard as “like a huge happy smile, with long rows of bright white gleaming keys spread out before me”. Another interview was with a man who had played the harmonium in his local church back in the 60s, in one of the most remote communities in the whole of Korea. He described how this amazingly precious instrument had had a cover over the keyboard which was usually locked, so every time he wanted to play it he had to wander over to the pastor’s house to borrow the key. Similarly, he described being deeply affected by seeing the row of keys shining brightly laid out before him, and, being a deeply religious man, he directly related the gleaming whiteness to the divine and to concepts like purity and hope. He also described how, as a struggling learner without a knowledgeable teacher, he had found the black keys (the “difficult keys”) particularly troubling! That kind of white/black symbolism is surely widespread across cultures…

So, in short, I suspect (though actually I’m only guessing because I haven’t done any research about those old keyboards) that the standardisation of the current white/black keyboard was due to matters of symbolism, fashion, a changing market for keyboard instruments, and material accessibility, cost, workability and durability. Very interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It comes to mind that whiteness seems to have been seen as something desirable, more aristocratic, “noble”—white skin and elegant lace, refined white sugar and flour, widely consumed in 18th-century Europe. The wiki article on sugar cites Peter Von Sivers et al., Patterns of world history with sources (2018):

“The charred animal bones added to the refining, for whitening the crystallizing sugar, were often supplemented by those of deceased enslaved people, thus contributing a particularly sinister element to the process.”

as well as Voltaire’s Candide:

“When we work at the sugar-canes, and the mill snatches hold of a finger, they cut off the hand; and when we attempt to run away, they cut off the leg; both cases have happened to me. This is the price at which you eat sugar in Europe.”

LikeLiked by 1 person