Lest anyone despair that my Chinese theme has recently been submerged

beneath football and tennis…

Having studied the qin zither obsessively for my first few years after coming to China in 1986, I then defected—feeling not exactly unworthy but just too immersed in the utterly different world of folk ritual life in the poor countryside (see Taking it on the qin). So my posts on this elite solo tradition (see qin tag) are partly an attempt to atone for jumping ship. The qin being a genuine ivory tower, we might try and see the wood for the trees (make up your own metaphors—though “Swirls before pine” is unbeatable!).

John Thompson has never wavered in his devotion to the qin. The documentary

- Music beyond sound: an American’s world of guqin (Lau Shing-hon, 2019)

(watch here; introduction here, with links)

makes a useful introduction to his lifelong work. Interspersed with lengthy sequences in which he plays his reconstructions of Ming pieces at scenic spots in Hong Kong and Hangzhou (in the mode of the literati of Yore), he reflects on his early life, his later path, and the state of the qin (biography here). Subtitles are in both English and Chinese. It’s something of an illustrated lecture, with testimonials.

From a background in Western Art Music (WAM), John was drawn to early music, as well as popular music and jazz. After graduating in 1967 he was confronted with the draft, serving in Military Intelligence in Vietnam (cf. Bosch) for eighteen months and making trips around East Asia. Already educating himself on Chinese culture, he returned to the USA to attend graduate school in Asian Studies, studying Chinese language and discovering “world music” through ethnomusicology, learning the Japanese shamisen. In those early days before the vast revival of traditional Chinese culture around 1980, he was understandably underwhelmed by the bland diet of conservatoire dizi and erhu solos. Instead, through reading the seminal work of Robert van Gulik, The lore of the Chinese lute, he became fascinated with the highly literate, prescribed microcosm of the qin. *

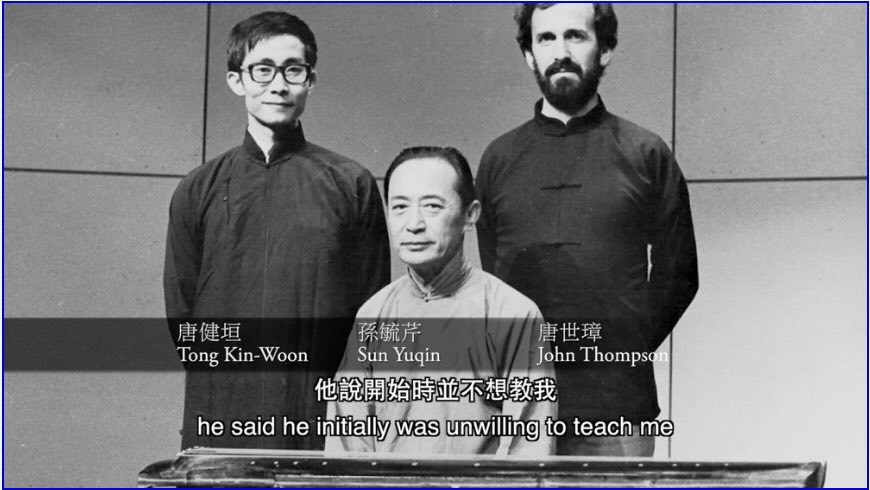

For this his best option was Taiwan, where from 1974 to 1976 he studied with Sun Yu-ch’in (1915–90); he then studied with Sun’s accomplished pupil Tong Kin-woon and the veteran Tsar Deh-yun (1905–2007) ** in Hong Kong, where he made his home. While learning from the qin renaissance in mainland China before and after the Cultural Revolution, he has forged his own path performing and researching early tablatures; setting forth from reconstructing the 64 pieces in the 1425 Shenqi mipu (6-CD compendium with 72-page booklet, 2000), he avidly sought out other early tablatures (CD Music beyond sound, 1998).

This may seem like a niche within a niche, and it’s an even more solitary pursuit, but the search for early pieces vastly expands the small repertoire handed down from master to pupil. All this work gave rise to his remarkable website.

In the PRC since the 1960s the traditional silk strings of the qin were largely replaced by metal, though they persisted in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and there are some advocates on the mainland. In keeping with his taste for historical recreation, John is a fervent advocate of silk strings (see this typically exhaustive essay).

In Hong Kong he also served as Programme Adviser for the Festival of Asian Arts from 1980 to 1998. In 2001 he married Suzanne Smith and they moved to New Jersey. Alongside his ongoing research he continues to engage with the qin scene in mainland China, where his work is respected. In 2010 he was among fourteen masters invited to take part in a festival at the Zhejiang Museum to play qin zithers from the Tang dynasty (!!!) (click here; for a 2019 festival, here). Like other wise qin players, confronted by the performance ethos of the conservatoire and the Intangible Cultural Heritage, he valiantly proclaims the literati aesthetic of self-cultivation.

* * *

While silkqin.com contains a vast range of material, John remains devoted to recreating Ming tablatures (still, I find it refreshing to hear him explaining that in such an oral tradition, there was no need for tablature!). The site contains ample material on the changing modern practice of the qin, but the social context before, during, and since Maoism (suggested in my series on the qin zither under Maoism) is not his main theme. Clearly the quietism the film evokes (cf. the spiritual quest of Bill Porter) is remote from the “red and fiery” atmosphere of the folk festivities that I frequent, but the social bond of PRC qin gatherings is also largely absent.

In the Chinese media the dominance of elite imperial culture is stark; online there is a wealth of information on the qin, whereas material for far more common traditions (such as the rituals of spirit mediums) is elusive. While John’s comments on the differences between early WAM and “Chinese music” are thoughtful, the vast variety of the latter cannot be represented by the qin; his dedicated study of one aspect of an elite tradition hardly allows room to absorb the wider context.

Bruno Nettl has wise words on “you [foreigners] will never understand our music” (The study of ethnomusicology: thirty-three discussions, ch.11). Conversely, I’m tired of the old clichés “Why should a foreigner study Chinese culture?” and “The monk from outside knows how to recite the scriptures“. Within China there are plenty of “monks to recite the scriptures”; no-one there would ever suggest that the qin is only understood by foreigners. John is indeed exceptional in his long-term in-depth study, but further afield this kind of thing is common—as is clear from the careers of other foreign scholar-performers such as Ric Emmert for Japanese noh drama, Veronica Doubleday for Afghan singing, or Nicolas Magriel for the sarangi in India. ***

In the sinosphere, whereas scholars rarely engage in participant observation for folk music, for the qin performing and scholarship tend to go hand in hand. So alongside the majority of qin players who have been content to transmit the repertoire that they learned from their teachers are some distinguished masters who unearth and recreate early historical sources—such as Zha Fuxi, Yao Bingyan, Tong Kin-woon, Bell Yung, Dai XIaolian, and Lin Chen. John’s work as performer and scholar is a particularly intense instance of this historical focus, a niche in the wider movement of Historically Informed Performance (HIP: see e.g. Richard Taruskin, John Butt).

Qin fraternities are now thriving in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and around the world. Senior figures on the Hong Kong scene include Tsar Teh-yun, Tong Kin-woon, Lau Chor-wah, and Bell Yung. Note also the work of Georges Goormaghtigh. The qin has long been a popular choice for foreign students to study in the PRC.

My usual point: given its tiny coterie of players, the qin is vastly over-represented in studies of Chinese music! But however niche, the qin is an essential aspect of literati culture through the imperial era, along with poetry, painting and calligraphy; and John Thompson’s work is an essential resource.

* For my own Long March to Chinese music around this time, see Revolution and laowai, and under Ray Man.

** See Bell Yung, The Last of China’s literati (2008), and the 2-CD set The art of qin music (ROI 2000 / AIMP 2014).

*** Note the contrasts between these four cultures, and approaches to them: Emmert working within the “isolated preservation” (Nettl) of noh, Doubleday as participant observer of an Afghan folk tradition soon to be decimated by warfare and fundamentalism, Magriel immersed in the changing social context of sarangi, and Thompson focusing on his own historical recreations of qin music.