with asides on religion and the alliance with China

In a curious spinoff from Euro 24, I came across the intriguing

- Phil Harrison, Inside the hermit kingdom: football stories from Stalinist Albania (2024) (extract here).

I trust you understand why I just had to read it. The modern history of Albania holds a grim fascination for outsiders. For a book clearly aimed at a popular market, Harrison’s obsession with football through the period seems to me on a par with that of scholars who document early Daoist ritual—or does his dogged optimism resemble mine in supposing I can make the modern travails of household Daoists palatable?!

Inside the hermit kingdom was “written by accident”, with major input from Irvin, an Albanian expat whose own story remains opaque. * While Harrison is aware of the dangers of portraits of Albania that “instil a sense of Western, capitalist superiority”, he inevitably paints a bleak picture, sometimes reminiscent of the spoof travel guide Molvania. The account is punctuated with “Iconic games” and vignettes on the careers of some of the major stars. There may not be such a thing as a casual reader here, but fair-weather fans may find it somewhat excessive to plough through some of the detailed reports of the most obscure matches ever.

The book opens in 1905 with the arrival of Christian missionaries in the “tribal backwaters” of mountainous Shkodër, beset by banditry, a Maltese priest founding the first club in 1912. The craze soon spread (cf. Futbol in Turkey, then and now).

Harrison soon plunges us into the vernacular of Albanian football terminology: positions on the pitch, organisations, and slang (humbje hapësire “a waste of space”).

He describes early internationals and the Zog-Mussolini axis. In April 1939 Mussolini’s forces invaded Albania, forcing King Zog into exile. We learn the stoies of two outstanding players among the Albanians recruited to Serie A, and of the Balkan Cup, held from 1946.

Clubs were now controlled by the army and police. Dinamo Tirana was founded in 1950—its stadium (above, via Fussball Geekz) built in 1956 by political prisoners supervised by armed militia, with many of the conscripts dying from exhaustion and injuries. In 1958 Partizani took part in the Spartakiad tournament in the GDR between army-affiliated clubs from the communist countries of the world.

“Long live the eternal and unbreakable friendship in battle between

the peoples of China and Albania!” Source.

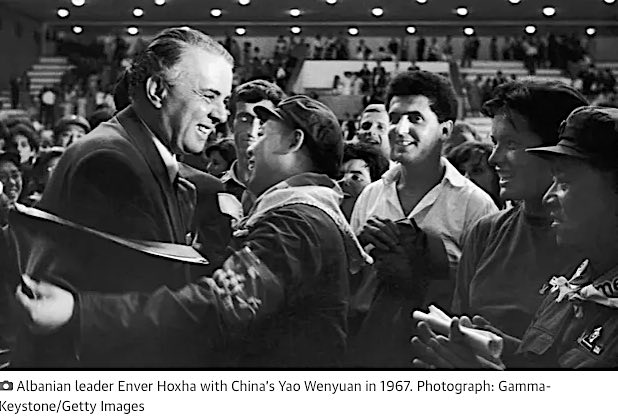

After the death of Stalin in 1953 Enver Hoxha’s relationship with the Soviet Union eroded, deteriorating further in 1956, until the rupture of 1961 which led to Albania’s solitary alliance with Maoist China. In 1957, the wave of Albanianization was evident in the political renaming of many football clubs. Harrison shows how the “golden goal” dates back to 1961 Albania.

Quite the most remarkable image I know:

former Buddhist monk with village disciples, suburban Beijing 1959.

With religion suppressed under Hoxha, it was replaced by the ritual and passion of Sunday-afternoon football, a “communal protest against oppression and servility”. Asking “How did football make Albanians feel?”, Harrison describes wages, bicycles, cigarettes (with an aside on their manufacture), alcohol, transistor radios, and racing pigeons. In Tirana from the 1960s, Gimi’s tiny kiosk was a hub of activity, not only selling newspapers and magazines but serving as ticket office for the Albanian Football Federation. At the stadium one stand, the Tribuna, was reserved for army, police, and Party members. The only refreshments available were fara grilled sunflower seeds, wrapped in paper cones sold from tezga usherette trays. For away matches, with train links rudimentary, diehard supporters would undertake a three- or four-hour bike ride, or hitch a lift on an army truck. Attempting access to foreign matches via satellite TV was fraught with danger.

Political anxieties were pervasive, with society surveilled by the Sigurimi secret police (eight of whose nine directors were themselves imprisoned and executed between 1943 and 1991), and the spectre of labour camps. In 1967 star player Skënder Halili was caught selling two wristwatches and sentenced to hard labour in the mines of Bulqiza, eventually cause of his death in 1982—attendance at his funeral marking a small-scale protest against the regime.

“Truth over religion”, screenshots.

In 1966–67, just as the Summer of Love was under way in the West, Hoxha, emulating Mao’s Cultural Revolution, clamped down still more harshly on religion and Western influence. He sponsored the making of the 1967 propaganda film E vërteta mbi fenë [Truth over religion] (do watch here). Among the casualties were Catholic priests, imams, and leaders of the Bektashi order (cf. Turkey; for another niche topic, see Shamans in the two Koreas). This was among several waves of violent religious persecution throughout the Soviet bloc since the 1920s. I’m keen to learn more of the underground maintenance of religious traditions, one of my main themes for China; in Skopje, for instance, just northeast from Albania, a remarkable 1951 film shows self-mortification rituals of the Rufai order.

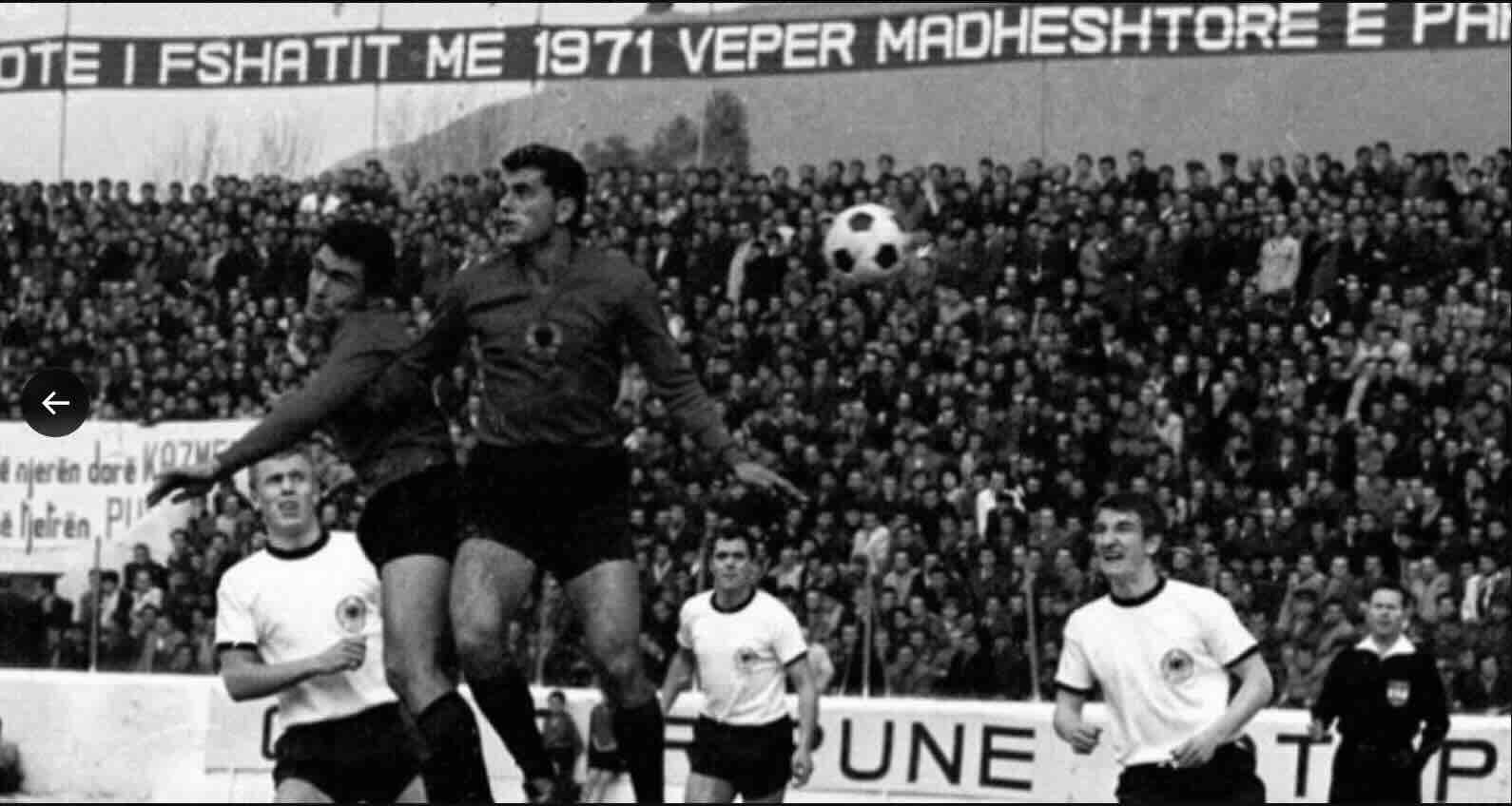

Back with the football, the 1966–67 “Championship of Coals” was subject to murky political interference. And in typical detail, Harrison describes the plucky goalless draw with West Germany in 1967 (above), watched from the Tribuna by Party stalwarts and Chinese dignitaries. I wonder about the lives of those visiting diplomats, who had somehow survived the Anti-Rightist purge, the Great Leap Backward and famine—now to find themselves exchanging cautious platitudes at a football match in a remote third-world country just as chaotic violence was being unleashed back home at the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution.

As purges continued, Albania became even more isolated. Harrison now devotes a substantial chapter to Fatmir Shima (with the catchy subtitle “the man from Xhomlliku”), father of his guide Irvin, who played in a lower division from 1969 to 1975 (cf. ordinary tennis players, Daoists, musicians, and so on), a temporary diversion from his career in agronomy. The chapter ends with another iconic game, between Tirona and Ajax, with predictable cultural clashes. Meanwhile Italian clubs were still scouting for Albanian players.

Under Hoxha the Gheg city of Shkodër was penalised, but its Vllaznia team rose to win the Kampionati Kombetar league in 1971–72, first of several successes over the following years—as the culture of Tirana at last no longer seemed so impregnable, people began to sense new possibilities.

Harrison continues to excel in arcane nerdiness with his account of the Dinamo club, which enjoyed success through the 1950s but then languished until the 1970s. Again he ends with an iconic game, between Partizani and Celtic for the 1979 European Cup—hair once again making a potential flashpoint. The game was “a sell-out, with ticket prices ranging from 7p to 21p”.

One of the great ironies of the piece is that Celtic’s players—upon their visit to Tirana during the dire, ramshackle days of the late 1970s—were privy to observing a failing city that was grim, penurious, and devoid of hope; a place of limited prospects.

In an act verging on satire, Vata—the first Albanian footballer to ever play in Scotland—made the reverse journey to his Celt predecessors 13 years later, keen to see what the world outside of Albanian borders had to offer. He now continues, by choice, to live in Hamilton.

By the 1970s, the Sino-Albanian collaboration suffered from Hoxha’s disillusion with China’s new rapprochement with the USA. Entirely isolated from 1978 once Chinese funding was discontinued, Albania was in an even more desperate plight. As audiences for the major games declined, people turned to futboll lagjesh “neighbourhood football”, a version of Italian calcetto. Harrison praises the creative improvisation of this five-a-side street style, “an inclusive, democratic idea set against an autocratic backdrop; an arcane act of defiance hiding within plain sight”, with vivid vignettes of the architecture of suburban east Tirana. But “with increased popularity came increased scrutiny”. “Enacting a class war”, a team from privileged Blloku ended up playing a rancorous game against a local Roma team, ending in a brawl and the sending of the Roma to labour camp.

By the early 80s, the regime was on its knees. As Hoxha lay dying, links were being forged with Italy, Greece, and Turkey. Within Albania, funding for football dwindled further. But apart from the long dominance of Tirana and Shkodër, KS Labinoti (in Elbasan county in central Albania) emerged as a contender. And the national team was making progress, at first through Shyqyri Rreli’s leadership of the under-21 team, and then in the 1984 World Cup qualifiers—with another blow-by-blow account of Albania’s magnificent 2-0 win over Belgium in Tirana. Albania narrowly failed to qualify for the Mexico 1986 World Cup, but the seed had been sown.

No nation has endured a more ill-tempered relationship with Europe’s footballing community than Albania. […] The Party remained unswervingly peevish in its interactions with the outside world, and this innate narrow-mindedness transposed itself on to sport.

Harrison documents the troubled domestic league, and encounters between Albanian and foreign clubs, over the whole period from the death throes of the regime from the late 1980s to the final collapse in 1992—whereupon Albania entered a period of anarchy and crushed dreams, prompting a mass exodus.

But somehow in football, clubs “trundled on”. The final chapter, “The other side of the abyss”, describes how clubs reverted to pre-Hoxha names, resentment emerged in on-pitch petulance and crowd violence, corporate sponsorship gave rise to a new kind of corruption, and criminal gangs flourished. While the domestic game has suffered, since 2014 the national side has been reborn—with the great majority of the squad playing outside Albania.

The new, great Albanian players ply their trade elsewhere and are rewarded with huge remuneration and lavish lifestyles, connected to their native people only by ethnicity, not locality or reality.

Memory remains strong:

The only thing people who lived through Albanian Stalinism still celebrate, or seem to agree on, is the football [… —] a football that unified fans and provided a balm during fifty years of horrific suffering.

One has to applaud Harrison’s boundless enthusiasm for such a niche project. Of course, football was not the only source of communal celebration; musical gatherings were an important part of social life at the domestic level (see under Musical cultures of east Europe, and Bernard Lortat-Jacob at 80). For other Albanian icons, see the unlikely bedfellows of Norman Wisdom and Mother Teresa. Note also posts under Life behind the Iron Curtain; more on football under A sporting medley: ritual and gender.

* With more detail on football than on social history, Harrison’s scant citations include Margo Rejmer’s collection and the title Albania—who cares? is suggestive. He would doubtless like to add Lea Ypi’s perceptive 2021 memoir Free: coming of age at the end of history, which I reviewed here.