A companion to Indian and world fiddles.

Image: Paul Childs/Reuters. Source.

Image: Paul Childs/Reuters. Source.

This summer, after yet another victory, Novak Djokovic paid homage to his daughter’s early steps learning the violin (video here!). This inspired me to survey the multiple ways of playing “our” Western violin, in Europe and around the world.

There are several issues in posture. How the instrument is positioned—roughly horizontally (on the shoulder or chest) or roughly vertically (on the thigh); and the bow hold. All of these are variable.

For over a century, the violin, along with the symphony orchestra, has been firmly established in urban middle-class milieus around the world (cf. Bach from Japan, and A Shanghai Prom). The Djokovices were more likely to choose the violin for their daughter, I concede, than the Serbian one-string gusle (featured here under “Bards”). But neither the violin that we now find in orchestras nor the way it’s played there is timeless; both are something of an anomaly, in both time and space.

Leaving aside the many other kinds of bowed fiddle (such as kemence and lira, or Indian sarangi, all commonly played on the leg), ways of playing the “Western violin” vary by period and region, class and context.

Leaving aside the many other kinds of bowed fiddle (such as kemence and lira, or Indian sarangi, all commonly played on the leg), ways of playing the “Western violin” vary by period and region, class and context.

How musicians engage with their instrument depends largely on genre and style—the kind of music they play for what kind of activity. A technique that evolves within an oral tradition—among friends, blending in ensemble, or for social dancing—is likely to differ from formal conservatoire training with a view to “performing” on the concert stage. Musicians find ways of playing that seem conducive to the sound-ideal they seek, coming to feel at one with the instrument so that it becomes part of the body.

Detail from Hans Memling, Musician angels, c1480.

In Europe, following medieval bowed fiddles like rebec and vielle (amply represented in iconography), precursors of the “modern violin” began to emerge in the early baroque, a period of great flux in Western Art Music. Treatises by leading player-pedagogues of the day reveal a range of views whether the instrument should be positioned on the chest or collar-bone, or under the chin. Among a wealth of discussion in the wake of David Boyden’s 1965 classic The history of violin playing from its origins to 1761, this article by Richard Gwilt makes a thoughtful introduction, with a second part here. The Essential Vermeer site also has a useful overview.

Left, Michel Corrette, L’Ecole d’Orphée, 1738

Right, Leopold Mozart, Violinschule, 1756.

Change continued through the 19th century, with research taking a lead from Robin Stowell. As composers and venues kept posing greater challenges on players, the instrument and its technique kept changing, adding more apparatus—chin-rest, shoulder-rest, elongated fingerboard, and so on. The bow evolved, and eventually metal strings replaced gut and silk. *

* * *

In folk traditions, ways of playing the violin have changed less than in Western Art Music. In many parts of the world, living folk styles may adapt techniques from early indigenous fiddles, or preserve those of the period when the violin was first introduced, often via colonialism. Here’s a little selection of many regional variants (note Peter Cooke, “The violin—instrument of four continents”, in The Cambridge companion to the violin, 1992, and for both WAM and folk traditions, The New Grove dictionary of musical instruments).

String trio with cimbalom at the Meta táncház, Budapest 1993. My photo.

String trio with cimbalom at the Meta táncház, Budapest 1993. My photo.

Besides the fiddle, note the supporting kontra.

Folk styles have been resilient in Transylvania (see under Musical cultures of east Europe). Do watch this amazing clip (from Bernard Lortat-Jacob, Jacques Bouët and Speranţa Rădulescu, A tue-tête: chant et violon au pays de l’Oach, Roumanie). And allow me to remind you of this splendid way of sounding the strings:

Still in Transylvania, this clip from Gyimes also features the gardon—a most distinctive way of playing the cello!

String bands are also at the heart of Polish folk traditions:

Józef Bębenek. Image from the excellent Muzyka Odnaleziona site; listen e.g. here.

Irish fiddlers use some fine bow holds—my personal award going to Mairead Ni Mhaonaigh (above).

Taranta: Luigi Stifani healing with violin in the heel of Italy.

I gave a little introduction to folk fiddlers of the Dauphiné in my playlist for Euro 24!

Folk fiddling traditions are common throughout north and south America.

“Unidentified fiddler” in the southern States. Source: Alan Lomax Archive.

“Unidentified fiddler” in the southern States. Source: Alan Lomax Archive.

See America over the water, and under Country.

In India (mainly in the southern Carnatic tradition) the violin is most exquisite both in posture and effect, players dispensing with the chair (cf. the qin zither) and seated on the floor, with the scroll resting on the right foot:

Sisters M. Lalitha and M. Nandini.

Peter Cooke comments on Bruno Nettl’s taxonomy of musical change:

The violin’s rapid adoption in Iran along with Western solistic tendencies suggest to him a basic compatibility with Western music, whereas in India the violin was only slowly absorbed into a strong, viable musical tradition—a case of modernisation of instrumentation rather than westernisation of style.

In north Africa, such as Morocco (listen here), and west Asia, such as rural Turkey (listen here), the violin is often played on the leg, like their indigenous fiddles—and like some early European fiddles, as well as members of the viol family (intriguing explorations by Fretwork here).

Uyghur musicians, complementing the ghijak and satar, also sometimes play violin on the leg, though more commonly they play it on (or off) the shoulder:

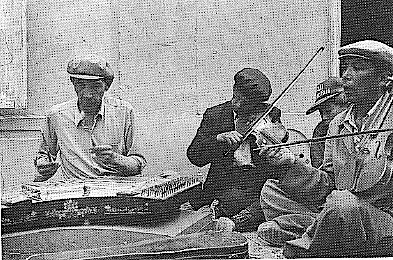

Wedding band, Kashgar 1988.

From booklet with 2-CD set Turkestan chinois/Xinjiang: musiques Ouïghoures.

See under From the holy mountain.

In my original roundup I featured some fine Uyghur violin playing in this recording of Raq muqam:

The players’ sound-ideal will be the major factor, whatever instrument they choose.

* * *

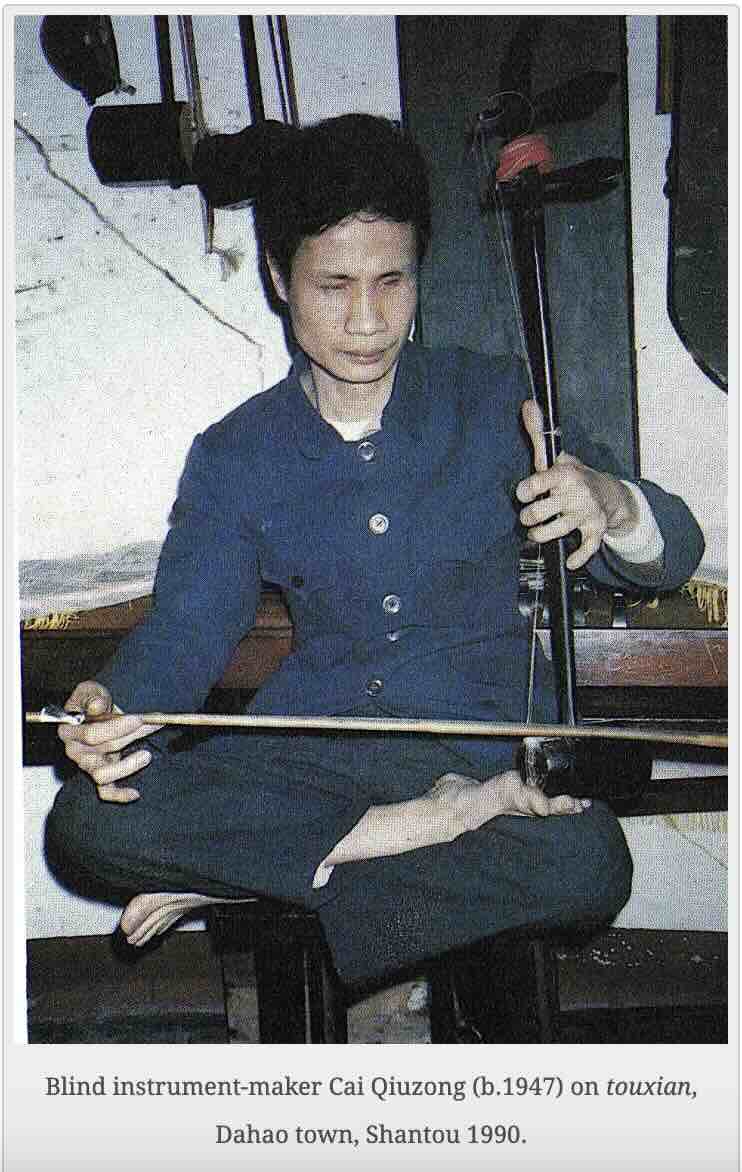

At a tangent, ways of playing Chinese fiddles have not always been so standardised as with the erhu of the modern conservatoires.

There’s a multitude of posts under the fiddles tag—on a lighter (yet instructive) note, try The Mary Celeste, and Muso speak: excuses and bravado (“It was in tune when I bought it”) .

Cf. Frozen brass.

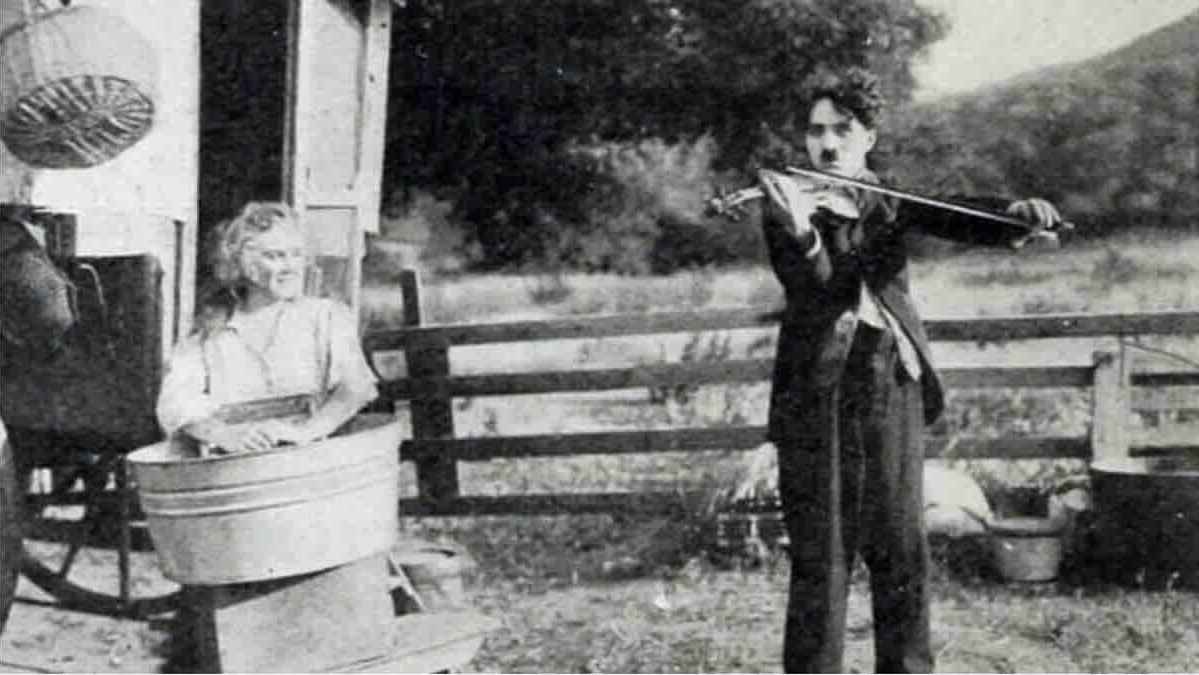

* We take it for granted that the left hand stops the strings while the bow is held in the right hand. Charlie Chaplin was one of rather few left-handed violinists:

A still from Chaplin’s 1916 film The Vagabond. Source.