As a card-carrying stammerer, I’m always on the lookout for fellow-sufferers—not least in China.*

I’ve already described my encounter with a stammering shawm player in Shaanbei (here, under “Status and disability”), and suggested a motto for the Chinese Stammerers’ Association, as well as noting an entertainingly crap Chinese therapy. I’ve noted how the public nature of Chinese life may force the stammerer to confront the issue.

Now (thanks to NBL on languagelog) I learn of the illustrious stammerer Deng Ai 鄧艾 (197–264 CE), a military general in the Romance of the three kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi 三國演義).**

On further study, this clue leads to a whole world of Sanguo nerds, largely through the medium of video gaming…

Chapter 107 of the Romance of the three kingdoms reads:

The other man is presently a lower official. His name is Deng Ai […]. He lost his father when he was young, but he always harbored great ambitions. Whenever he saw mountains or valleys, he would instinctively point out the best places to station troops, store grain, or stage an ambush. Everyone else laughed at him, but Sima Yi appreciated his talent and came to include him when discussing military strategy. Deng Ai has a speech defect. He always stutters when he’s trying to speak, so that whenever he had to make a report he couldn’t help saying ‘Ai Ai…’.*** Sima Yi once teased him about it, asking him, “You’re always saying ‘Ai Ai’. How many Ai’s are there?”

But Deng Ai immediately replied, “They say O Phoenix, O Phoenix, when there’s only one phoenix.” From this, you can see that he has a quick and alert mind. You must watch out for these two people.

姓鄧,名艾,字士載。幼年失父,素有大志。但見高山大澤,輒窺度指畫,何處可以屯兵,何處可以積糧,何處可以埋伏。人皆笑之,獨司馬懿奇其才,遂令參贊軍機。艾爲人口吃,每奏事必稱『艾,艾』。懿戲謂曰:『卿稱艾艾,當有幾艾?』

艾應聲曰:『鳳兮鳳兮,故是一鳳。』其資性敏捷,大抵如此。二人深可畏也。

Putting down a heckler with a quote from the Analects of Confucius—now that’s niche! Beat that, Stewart Lee. Later, as Deng Ai rose to power, he mastered his stammer, addressing his troops—another tough gig.

Here’s a typically cute Chinese video!

Actually, this illustrates how a certain insider knowledge on a seemingly technical topic may illuminate our studies—such as geographical and topographic features in early literature, or the availability of materials for painting or sculpture; or for Daoist ritual, how participant observation, an understanding of vocal, percussive, and instrumental melody in performance, should be a basic aspect of research. “Yeah?”

* * *

Some useful Chinese sites (like this) list many other illustrious Chinese stammerers, ancient and modern. Starting with the early legalist philosopher Han Feizi 韓非子, and the poet Sima Xiangru 司馬相如, there’s a g-glut [measure word] from the pre-Tang era. For the aficionado of Tang poetry we have Meng Jiao 孟郊, writing (and stammering) in the aftermath of the cataclysmic An Lushan rebellion. (In a post on stammering songs I speculate whether there’s a link between fluency and social trauma.)

Celebrated 20th-century stammerers (putting aside Wang Guowei, who seems to belong in Confucius’s “deliberate” category) include the philosopher Feng Youlan 馮友蘭, influential both within and beyond China.

Gu Jiegang and his family, 1954.

Most notable for my tastes is the folklorist Gu Jiegang 顾颉刚 (1893–1980), to whose 1925 fieldwork on Miaofengshan one often refers [Innit though—Ed.]. He might have made a drôle companion to interpret my own questions in the field. Lu Xun abruptly goes right down in my estimation as I learn that in their literary feud he uncharitably took the piss out of Gu’s impediment (B-b-bastard).

* * *

But my favourite reference to early Chinese stammering has to be a passage from Sima Qian’s Records of the grand historian (Shiji), to which the erudite Hannibal Taubes, always alert to niches that might attract me, alerted me. It appears in the biography of Chancellor Zhang 張丞相列傳, referring to the stammering minister Zhou Chang:

及帝欲廢太子,而立戚姬子如意為太子,大臣固爭之,莫能得;上以留侯策即止。而周昌廷爭之彊,上問其說,昌為人吃,又盛怒,曰:臣口不能言,然臣期期知其不可。陛下雖欲廢太子,臣期期不奉詔。上欣然而笑。既罷,呂后側耳於東箱聽,見周昌,為跪謝曰:微君,太子幾廢。

In Nienhauser’s 2008 translation (p.213):

When the Emperor wanted to depose the heir and install Ju-yi, the son of Beauty Ch’i, as the heir, the great ministers firmly challenged this, but none was able to win him over. The Emperor [eventually] because of the Marquis of Liu’s strategy desisted. But Chou Ch’ang having been mighty in the court disputes, the Sovereign asked him for his arguments. Ch’ang was a man with a stutter and furthermore was filled with anger. He said, “My mouth cannot speak, but surely I kn-kn-know this is not permissible! Even if Your Majesty wants to depose the Heir, your subject surely will n-n-not accept the decree!” The sovereign laughed delightedly. After [court] had been dismissed, Empress Lü, who had been eavesdropping from the chambers on the eastern side, saw Chou Ch’ang, knelt down to him, and thanked him.“Without you, Sir, the Heir would certainly have been deposed.”

More um, fluently, Joseph Needham and Christoph Harbsmeier (Science and civilisation in China, volume 7: the social background, part 1, pp. 43–4) translate the relevant passage thus:

“I cannot get the words out of my mouth.” he replied. “But I know it will n-n-n-ever do! Although Your Majesty wishes to remove the heir apparent, I shall n-n-n-ever obey such an order.”

Indeed, even for those who are otherwise fluent, having to speak truth to power before a capricious amoral emperor might bring on a speech impediment. One inevitably thinks of the current wranglings around the White House—for my Hollywood screenplay I have Michael Palin lined up as Zhou Chang, with a bit part for Stormy Daniels as Concubine Ji.

While the great Han scholar Michael Loewe was introducing me to the riches of the Shiji all those decades ago, he somehow omitted to draw my attention to this—out of tact, perhaps?!

This topos is sometimes combined with an allusion to the Deng Ai story in the phrase qiqi aiai 期期艾艾.

Hannibal has further supplemented my list of illustrious Chinese stammerers with a biographical sketch of the muralist Dong Yu 董羽. As described in Song[/sheng]chao minghua ping 宋[/聖]朝名畫評 by the Song-dynasty author Liu Daochun 劉道醇, Dong Yu was an attendant to Li Yu 李煜 (Li Houzhu), last emperor of the short-lived southern Tang in the Five Dynasties period. A native of Piling in Jiangsu, Dong excelled at depicting dragons, fishes, and seas. The sketch opens with the comment “with his stammer, he couldn’t get his words out, so he was known as The Mute”.

Hannibal has further supplemented my list of illustrious Chinese stammerers with a biographical sketch of the muralist Dong Yu 董羽. As described in Song[/sheng]chao minghua ping 宋[/聖]朝名畫評 by the Song-dynasty author Liu Daochun 劉道醇, Dong Yu was an attendant to Li Yu 李煜 (Li Houzhu), last emperor of the short-lived southern Tang in the Five Dynasties period. A native of Piling in Jiangsu, Dong excelled at depicting dragons, fishes, and seas. The sketch opens with the comment “with his stammer, he couldn’t get his words out, so he was known as The Mute”.

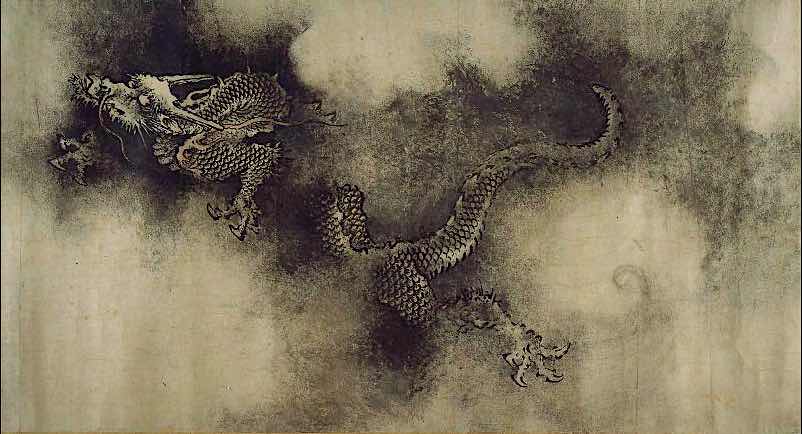

None of Dong Yu’s ouevre seems to survive, so here’s a detail from the Nine dragons handscroll by Chen Rong, from 1244:

Gratuitously, here’s a dragon-shaped cloud above the Sea of Marmara this summer:

For a wealth of images from Dragon Kings temples in north China, note Hannibal Taubes’s website.

Note also the fine songs about Coronavirus by the stammerer Zhang Gasong.

So we can add such luminaries to the list of historical stammerers like Moses and Demosthenes, and later Marilyn Monroe and Ed Balls—one of those niche pub-quiz topics, like left-handed calligraphers, or Norman Wisdom and Albania.

But what about the suffering workers, eh?!

* BTW, more colloquial than the standard kouchi 口吃 is jieba 结巴 (jiejiebaba!), but still more common in north China is jieka 结卡.

** See, I Have No Kulture (paltry excuse: I’ve been busy with Tang poetry, and Daoist ritual under Maoism).

*** Call me a pedant, but while it’s perfectly possible to stammer on a vowel (and a diphthong), written Chinese doesn’t capture the likely nature of the impediment here. Repeating whole syllables or words is less common than repeating initial c-c-consonants.

Pingback: Confucius he say—slowly | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: We have ways of making you talk | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Temple fairs: Miaofengshan and Houshan | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A Confucius mélange | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: More stammering songs | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Chinese stammerers: an update! | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A 2019 retrospective | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A Tang mélange | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Coronavirus 2: songs from Gansu, and blind bards | Stephen Jones: a blog