At last I’ve got round to reading

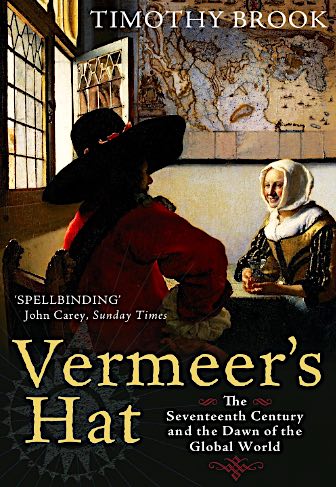

- Timothy Brook, Vermeer’s hat: the seventeenth century and the dawn of the global world (2009).

The author, a specialist in Ming China, sets out to write a “global history of the intercultural transformations of 17th-century life”, using Vermeer’s paintings to “open doors” onto the social history of the day (cf. Music in the time of Vermeer). Such an approach has evidently become a tradition in art history—from my very limited experience, it somewhat recalls the style of Michael Baxandall and Michael Jacobs (see On visual culture), on the far broader canvas of the whole globe.

As Kathryn Hughes comments in her splendidly-titled review “Where did you get that hat?”,

while most of the figures in the paintings of the Dutch golden age look as if they have never strayed more than a day or two from Delft, the material world through which they move is stuffed with hats, pots, wine, slaves and carpets that have been gusted around the world by the twin demands of trade and war. […]

Behind the serene chinaware and glinting silver coinage that furnish Vermeer’s burnished interiors lay real-life narratives of roiling seas, summary justice, and years of involuntary exile. […]

What Brook wants us to understand is that these domains, the local and the transnational, were intimately connected centuries before anyone came up with the world wide web.

(More reviews e.g. here, here, here, here).

The 17th century was an age of “second contacts”:

First encounters were becoming sustained engagements; fortuitous exchanges were being systematised into regular trade; the language of gesture was being supplanted by pidgin dialects and genuine communication.

Things, and people, were moving around on a global scale.

Chapter 1, “View of Delft”, introduces the Dutch East India Company (VOC); the narrative soon expands from Delft and Amsterdam, with Spain and Portugal also trading in southeast Asia.

Chapter 2, “Vermeer’s hat”, sets forth from Officer and laughing girl, with a fine discourse on hats in the artist’s time, leading seamlessly to Samuel Champlain’s encounter with the Mohawks at the Great Lakes in 1609, the crucial role of the new technology of weaponry, and the beaver hat. Brook always makes connections:

I spend my summers on Christian Island, which is now an Ojibwa reserve, and I cannot walk the dappled path that angles past the place where the children are buried without thinking back to the starvation winter of 1649–50, marvelling at the vast web of history that ties this hidden spot to the vast networks of trade and conquest that came into being in the 17th century. The children are lost links in that history, forgotten victims of the desperate European desire to find a way to China and a way to pay for it, tiny actors in the drama that placed Vermeer’s hat on the officers’ head.

Indeed, “the lure of China’s wealth haunted the 17th-century world“—and the lure of china, theme of Chapter 3, “A dish of fruit”, based on Vermeer’s Young woman reading a letter at an open window. The British East India Company enters the fray, with their battles in St Helena. We learn of the spread of blue-and-white, in Persia, India, Mexico; exploits in the South China Sea, Macao, and Zhengzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian; and in Suzhou, Wen Zhenheng’s A treatise on superfluous things (cf. another inspired book by Craig Clunas). Brook addresses class and aesthetics. He contrasts European taste for foreign objects (“stirring no contempt or anxiety”) with Chinese mistrust of the wider world, “a source of threat, not of promise or wealth, and still less of delight or inspiration”.

In Chapter 4, “Geography lessons” based on Vermeer’s The geographer, Brook addresses the way that “the great minds of Vermeer’s generation were learning to see the world in fresh ways”. By way of the Delft draper, surveyor, and polymath Antonie van Leeuwenhoek we are taken again to the South China Sea—Manila and Macau, and coastal China, where besides Red Hairs (Dutch), Dwarf Pirates (Japanese), and Macanese Foreigners, African slaves (servants of the Portuguese) as well as Muslim merchants, were also seen. Jesuits such as Paolo Xu and Matteo Ricci play a significant role.

Chapter 5, “School for smoking”, is another fascinating exploration, covering the diffusion of the new habit around the world; “every culture learns to smoke in a slightly different way”. From images in Dutch painting and porcelain, Brook moves again to China, exploring the three routes by which tobacco entered the country. Writing in 1643, Yang Shicong noted the new taste in Beijing, whither it had spread rapidly from the southeast coast. In 1639 the Chongzhen emperor decreed that anyone caught selling tobacco in the capital would be decapitated. The colloquial term “eat smoke” (chiyan), still heard in rural China, was already in use. In the New World (documented from 1505), tobacco was used to “move between the natural and supernatural worlds and to communicate with the spirits”—a function which it still serves in Chinese ritual today. It was thought to have both spiritual and medicinal properties. Moreover,

In daily life, tobacco was an important medium of sociability that, like healing, was something that benefitted from the spirits’ kind support. Managing social relations on a personal or communal level required thoughtfulness and care, and could best be accomplished when the spirits were on one’s side. Burning or smoking tobacco was a way of propitiating the spirits if they were in an ugly mood—as they so often were—and inducing them to bless your enterprise.Sharing a smoke at a tabagie was done in the presence of the spirits, and it helped the smokers find consensus when differences arose.

In China this is another important aspect of social and ritual life that tends to get neglected in our focus on ritual texts. In 1924 Berthold Laufer praised smoking in an egregious misapprehension with grains of insight:

Of all the gifts of nature, tobacco has been the most potent social factor, the most efficient peacemaker and benefactor to mankind. It has made the whole world akin and united it into a common bond. Of all luxuries it is the most democratic and the most universal; it has contributed a large share towards democratising the world.

Brook offers perceptive asides on witchcraft in Europe, class, gender, a tobacco ballet in 1650 Turin—and slavery. And he notes how the habit of smoking morphed into opium dependency in the 19th century—another tragic story of the ravages of trade.

Chapter 6 departs from Vermeer’s Woman holding a balance to discuss the role of silver, crucial to the world economy of the day, travelling from Potosi in the Andes to Europe and Asia—with erudite discussions of coinage and morality.

Chapter 7, “Journeys”, interrogates a painting by Hendrik van Der Burch showing an African servant boy (cf. Jessie Burton’s novel The miniaturist, evoking the changing world of 17th century Amsterdam). Brook goes on to describe five journeys to distant shores: Natal, Java, a Korean island, Fujian, and Madagascar. He ponders pictorial representations of Biblical scenes (cf. Balthasar).

In the final Chapter 8, “Endings: no man is an island”, Brook ties the themes together, with discussions of translators, the role of the state, and the concept of a common humanity.

If we can see that the history of any one place links us to all places, and ultimately to the history of the whole world, then there is no part of the past—no holocaust and no achievement—that is not our collective heritage.

Yet as Brook shows throughout, all this came at vast human cost: warfare, shipwrecks, ruined lives. He appends a useful list of Recommended reading and sources.

Vermeer’s hat is a virtuosic, stimulating piece of writing.