Shawm-and-percussion bands occupy a lowly but vital position in folk cultures around the world. Throughout rural China they are the major performers for life-cycle and calendrical rituals, as is clear from the monumental Anthology of folk music of the Chinese peoples. *

For folk expressive cultures, our evidence for change before the early 20th century is limited to the inspection of historical documents and iconography; for the whole modern period since the Republican era, our sources are hugely enriched by fieldwork. Continuity with the imperial heritage tended to be obscured by the political interventions of the Maoist era, but was revealed again by the massive revival of local traditions in the early reform period of the 1980s—documented in the Anthology and coinciding with my own fieldwork.

In two books (with DVDs) I introduced shawm bands of north Shanxi (2007) and Shaanbei (2009)—see under Other publications. In my survey Walking Shrill I outlined their lowly milieu: however indispensible,

shawm bands were always at the bottom of the social pile. Virtual outcasts, they were often illiterate, bachelors, opium smokers, begging in the slack season, associated with theft and violence.

For the period before and after the 1949 Liberation, some players were visually impaired, as shown in the rich material of the Anthology; while I still came across senior blind musicians during my own fieldwork in north Shanxi and Shaanbei through the 1990s, fewer remained active (similarly, sighted bards were encroaching on the livelihood of blind performers). But most sighted players still had a somewhat unsavoury reputation, partial to alcohol and amphetamines.

Coinciding with the revival, the Anthology fieldwork came at the most opportune time to document local traditions. But today’s society is already very different from that of the 1990s, with pervasive changes escalating . So I’m curious to learn how widely the outcast status of shawm bands still applies. We certainly can’t draw conclusions about the broad picture on the basis of the ideology of the urban troupes and conservatoires—the mere tip of a vast iceberg. Much of my work documents underlying rural customs that resist or circumvent such values—as they did even during the Maoist era. A different mode of state intrusion (or shall we say “presence”—e.g. Guo Yuhua ed., Yishi yu shehui bianqian) may now apply, but it’s never the whole story.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

Chang Wenzhou’s big band at village funeral, Mizhi 2001.

I was not entirely oblivious to recent change. I described how shawm bands were turning to pop music, incorporating the “big band”, adding trumpet, sax, and drum-kit, in north Shanxi (2007, pp.30–38) and Shaanbei (2009, pp.149–53); and for the latter region I gave a vignette on the image presented by an urban troupe (pp.210–12, recast here). I have noted how the new wave of pop culture since the 1980s promised to be more successful in erasing tradition than political campaigns during the decades of Maoism.

* * *

Detailed ethnographic updates are scarce. At SOAS, Feng Jun has just completed a fine PhD thesis on paiziluo shawm bands in southeast Hubei—an instrumentation which, perhaps exceptionally, dispenses with drum in favour of gongs.

Left, paiziluo after dinner at funeral.

Right, two paiziluo bands performing simultaneously in the ancestral temple.

Images courtesy of Feng Jun.

Feng Jun discusses the role of these bands in funerals and ancestral ceremonies, which still require a largely traditional repertoire—whose modal variations she analyses in detail. But she also highlights weddings, which have long featured more innovative popular pieces (cf. my Shaanbei book, pp.188–9, and DVD §D2). Performers now “selectively appropriate diverse musical spectacles, particularly through the national Spring Festival Gala, and project their own re-imagining of these spectacles in the ceremonial spaces of village rituals.”

Left, brass band performing for village wedding.

Right, dancing to the song Rela nüren (“Hot and spicy women”).

The increasing participation of women is another trend that I haven’t kept up with. I noted how shawm-playing men might encourage their daughters to take part in the family band, at least before marriage, since the 1980s; but in Hubei, with men often absent as migrant labourers in distant towns, married women now not only take part in paiziluo groups but form their own brass bands—another radical innovation. Feng Jun goes on to unpack the practical impact of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH), now an unavoidable topic—where a plethora of detached academic analysis detailing its negative effects never manages to convey just how damaging it is.

In Hubei Feng Jun found no such prejudice against shawm-band musicians as has been documented in north China—which she explains by the greater lineage cohesion of southern society. This makes me wonder if their exclusion from mainstream society is less widespread than my material suggests. So we might consider two caveats referring to space and time: differing long-term regional customs, and recent social change. For the former, we might go back to other provincial volumes of the Anthology for more clues. As always, there will be regional variations, depending partly on the poverty and insularity of a locale. For the mid-20th century, I suspect my impression still holds good for the north and northwest, and for the Shandong–Henan region; perhaps less so as one goes further south.

And even in more backward areas, as the country has become more affluent and villages further depopulated by migration to the cities, peasants seek upward mobility through education while the influence of national trends expands greatly through social media. For some shawm families, other more reliable and salubrious livelihoods beckon; but those younger generations who still take up the trade of their elders tend to spruce up their former lowly image.

Musical change is perhaps more evident in public events (including temple fairs), that can be exploited by cultural authorities, than in domestic rituals such as funerals or the activities of spirit mediums. Household Daoists are also invited for funerals in southeast Hubei—their rituals doubtless also changing, if less obviously than those of the shawm bands.

All this is probably a question of emphasis: pop music was already part of the rural scene by the time the Anthology was being compiled, but was mentioned there only in passing. Innovations that I still considered minor only twenty years ago would now be a significant part of our description.

* * *

In Walking Shrill I outlined the minor presence of the suona in the conservatoire (cf. jazz, which has also gained admission to the academy since the Golden Age). Indeed, while the term suona is used in historical sources, it now belongs to the conservatoire, folk musicians preferring a variety of local terms; where they do adopt the word, it is itself a badge of modernity.

Though the shawm lacks the suave image of erhu, zheng, or pipa, it has long had a foot in the conservatoire door. Under Maoism since the 1950s, state-funded Arts Work Troupes featured suona solos by celebrated “folk artists” such as Ren Tongxiang (heard e.g. on the archive CD Xianguan chuanqi). After the 1949 Liberation, some shawm players from hereditary traditions became conservatoire teachers, training younger generations from similar backgrounds—like Liu Ying, who found his way from rural Anhui to join the Shanghai Conservatoire soon after the downfall of the Gang of Four in 1976. And far more than other instrumentalists in the conservatoire, Liu Ying’s pupils tended to come from a poor rural background, the Shandong–Henan region (see here, and here) remaining the heartland for such recruitment.

Even if rural musicians won’t necessarily make a lot more money in this new environment than they would back home (cf. Ivo Papazov—see here, under “Bulgaria, Macedonia”), they will naturally leap at any prospect of upward mobility. The troupes and conservatoires make a promising route to urban registration, an escape from a tough life (cf. The life of the household Daoist); still, they will never be able to absorb more than a minor intake.

As to the shawm band musicians who remain in the poor countryside serving life-cycle and calendrical ceremonies, their lives and livelihoods are changing. But thanks to the internet, the polished style of the conservatoire virtuosi is one strand among a range of new images to emulate.

Chinese scholars write academic theses on regional shawm-band traditions—although they are surely at a disadvantage under a system that still discourages the participant observation that is routine in Western ethnomusicology. So I suppose the idea of a PhD in suona studies, combining performance and writing, shouldn’t seem so comical to me. “China’s first suona Ph.D. is ready for her solo” is perhaps only a clickbait headline for the likes of me (cf. this more detailed article in Chinese).

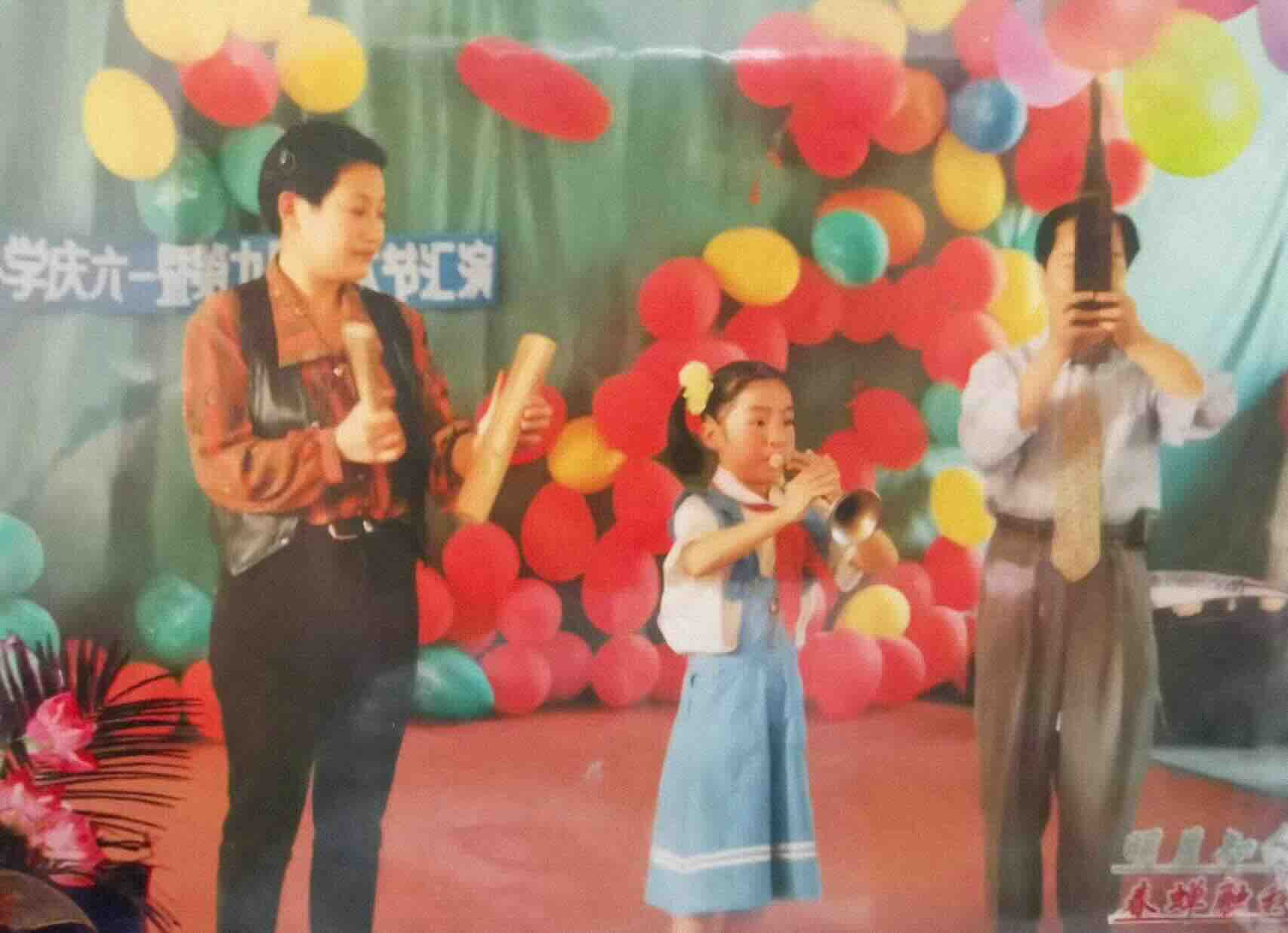

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents. Source.

A young Liu Wenwen performs with her parents. Source.

At the Shanghai Conservatoire, Liu Ying’s pupil Liu Wenwen (b.1990—no relation!) recently gained China’s first PhD in suona, for which she had to perform three solo recitals and write an original dissertation. Her father Liu Baobin is descended from a shawm lineage from southwest Shandong, and is said (here) to be a pupil of Ren Tongxiang; her mother Liu Hongmei comes from a long line of shawm players in Xuzhou in northwest Jiangsu. Unlike in the northwest, in the Shandong–Henan region the custom of absorbing female players into family bands appears to date back several decades. Practising from childhood under her parents’ guidance, Liu Wenwen began making journeys to Shanghai for lessons with Liu Ying, and by the age of 15 she enrolled at the conservatoire to study formally with him.

As household Daoist Li Qing found in north Shanxi when he escaped the worst of the famine by taking a job in the regional Arts Work Troupe, the conservatoire style consists largely of quaint “little pieces”, often using kaxi techniques to mimic bird-song. This repertoire never approaches the complex grandeur of traditional shawm suites (note Dissolving boundaries); and even when “little pieces” are a significant component of rural practice, they are performed (and creatively varied) within the context and rules of lengthy life-cycle and calendrical ceremonies.

In the troupes and conservatoires we also find change through different eras—not least in the spin put on the rural background. Under Maoism the suona soloists of the Arts Work Troupes fostered the image of peasants nobly toiling for the common cause, whereas publicity for today’s suave virtuosi deflects the political spin for a more glamorous image, with aspirational hype about “ascending to the hall of great elegance” (deng daya zhi tang) on the concert stage, trumpeting the success of modernisation. In both images the actual conditions of the countryside are irrelevant.

Left, village band performing for funeral, Shaanbei 1999.

Right, Liu Wenwen accompanied by Tan Dun. Source.

In the case of Liu Wenwen, gender again plays a role in innovation. On the international stage, her playing has made another bandwagon for composer Tan Dun. The differing contexts entail adaptations in costume; the headscarf of the male peasant, emblem of the revolution, is now only paraded for kitsch staged performances and the ICH. **

It’s worryingly easy for the conservatoire tip of the iceberg—and the ICH—to obscure both local traditions and the pervasive changes taking place in the countryside, revealed in fieldwork like that of Feng Jun.

See also The folk–conservatoire gulf, and Different values.

* Besides the Anthology‘s introductions to regional traditions, the volumes conclude with useful sketches of groups, and biographies; for some instances, see e.g. Liaoning, Tianjin, Henan, Fujian, Ningxia. See also Two local cultural workers.

** I wrestled with this issue in presenting the Hua family shawm band on stage; after teething issues in Washington DC in 2002, I was able to opt for suits without ties, a cool look that doesn’t conflict too much with their casual local attire. The band may have been gratified by their brief residency at SOAS in 2005, but, free of pressure to glamorize their image or simplify their repertoire, it was very different to the long-term cultural shift embodied by players like Liu Ying and Liu Wenwen.

BTW, when visited by academics, peasants may initially appear impressed; once they discover that we’re totally hopeless at any useful, practical task, their respect may turn to consternation as our credentials prompt envy at our mystifying ability to cadge an “iron food-bowl”. This is an element in the Li family’s magnificent Joke, which follows the final credits of our film!