In the recent CHIME newsletter (subscribe here, under Newsletter), by contrast with Frank Kouwenhoven’s renewed project on temple festivals in Gansu, he reports on the CHIME “travelling fieldwork conference” last November under the aegis of the Zhejiang Conservatory of Music in Hangzhou.

Such a project may sound attractive, changing the focus from dry lectures to engagement with local performers. But despite the best intentions of the regional organisers, the event turned out to be at the mercy of Heritage kitsch. As Frank recalls, things were a good deal more relaxed and more open-minded in 2006, when CHIME held a similar conference in Yulin, Shaanbei. However, I suspect such brief “hit-and-run” missions with large organised gatherings of foreigners and outsiders are inevitably flawed—as Frank comments, “beset with problems, unwanted side-effects, and distortions of local culture”.

In rural China, soundscapes are based in local ritual. But

sadly, participants were mainly taken to tourist villages, which featured many sanitised and commercialised versions of local traditions. […] Perhaps the higher echelons of the conservatory leadership, who picked these targets, were keen to project first and foremost a “modern”, more glamorous image of China’s rural musical cultures. But was the idea that we, the participants, would view the tourist shows as authentic stuff? Many of us happen to be seasoned music scholars, we have already done quite a bit of field research on local genres, perhaps in other parts of China, and sometimes for years or decades on end. But the rest of us, those mainly engaged in educational work or research outside China, would clearly be just as aware that villages in China do not normally require visitors to buy entrance tickets, nor harbour folk singers who dress up in fancy costumes and make ballet-like movements while they sing.

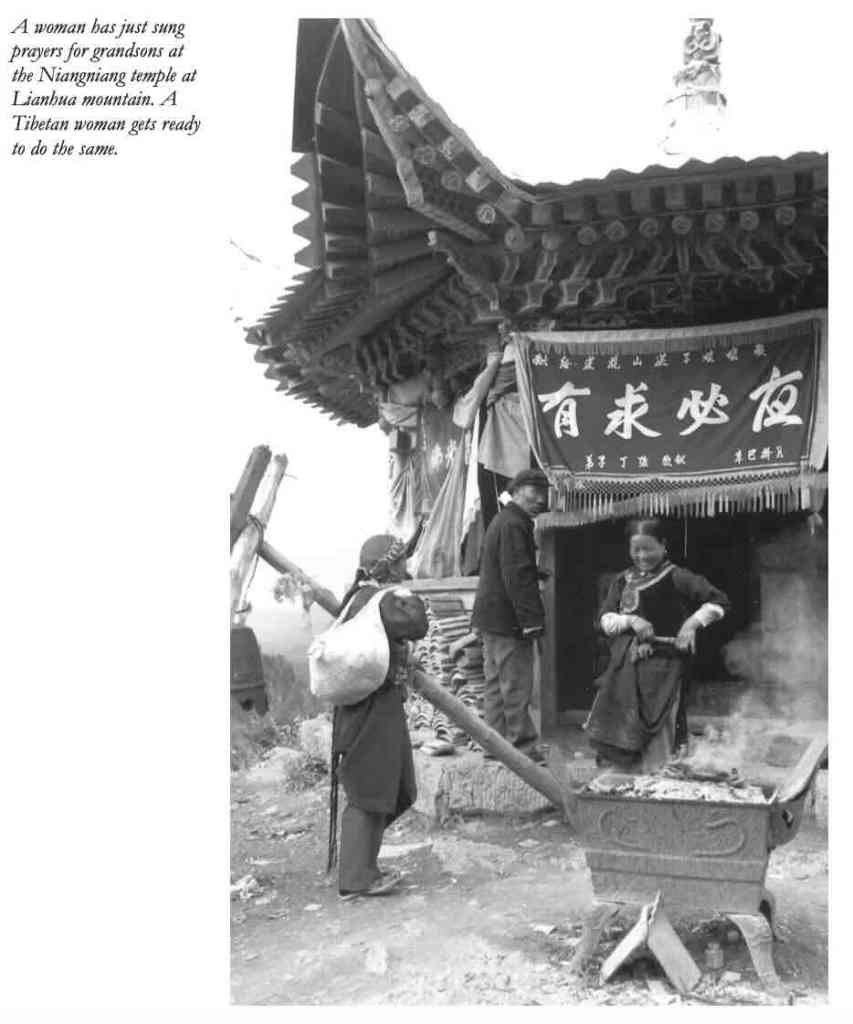

Why not visit a Daoist temple instead, with priests performing ritual opera, a fascinating genre definitely available in Zhejiang […]? Or why not schedule one trip to a local temple fair, where one might come across a whole range of local folk rituals and ceremonies, not tampered with by professional “stage directors”, village heads, or tourist managers?

At Shengzhou the trip sampled Yueju 越剧 opera (now associated primarily with female performers, also in male roles), comparing the student performances at the professional opera school with an amateur group performing at a nearby temple.

The school students behaved rather nervously, as if they were doing auditions, whereas the amateurs seemed more relaxed. As one might expect, the amateurs sounded more folksy and flexible, more rough also in their use of dialect, their tunes were more angular, less polished, mellifluous or spun-out than the “academic” ones. The amateurs were playing mainly for their own enjoyment, or for us and a small in-crowd of connoisseurs, in contrast to the more official shows which teachers and students of the Yueju school may present at commercial stages for paying audiences. […]

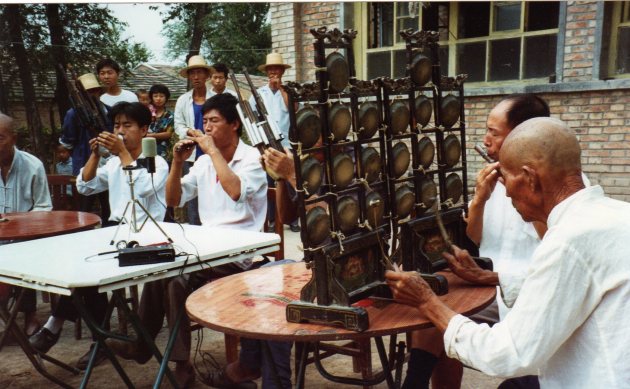

Wuju instrumentalists playing long trumpets.

In Jiangshan they also sampled Wuju 婺剧 (aka Jinhua opera). They found that dividing lines between “professional” and “amateur”, between state-funded and private enterprises, not always predictable or clearly defined.

Perhaps the most inspiring group they encountered was a group of string puppet players, again in Jiangshan.

They turned up once every two weeks at the tourist village to do some shows, which is also where we encountered them, but most of the time they’d perform puppet shows in the framework of local temple festivals.

Frank reflects ruefully:

Whether it is wise to undertake another conference on a basis of “traveling fieldwork” in China remains a question. It may well be that the country, in its current very politicised phase, is not sufficiently open to the full potential of rural musical traditions (especially religiously inspired ones).

* * *

In Hannover and Hildesheim the previous month, CHIME held a more conventional academic conference exploring such issues, with the theme of Sustainability and Chinese music.

The splendid Xiao Mei gave a keynote speech showing how ethnic minority performers have adapted admirably to changing times, with few concessions to the traditional character of their music. Frank summarises:

Mobile phones and modern means of transport have come to play crucial roles in the organising of traditional gatherings, and in the transmission of songs and tunes. It means that the traditional spaces designated for meeting one another and joining musical rituals (e.g. temples, sacred sites, mountain tops etc) have greatly expanded: singers may now also join events online, from a remote distance.

In another fine keynote, Huib Schippers pointed out that China is currently spending more money on Intangible Cultural Heritage than any other country in the world. As he pointed out, local people frequently feel disempowered when dealing with authorities. “Only rarely do we hear stories from anywhere in the world where [members of] communities have a real sense of agency in preserving their music”.

And things may become still more difficult in China because of the strong weight attached there in state propaganda to “progress” and “modernisation”. Schippers quoted Gao Shu, a scholar who states that “when traditional musicians in various regions know they will be visited by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, they change their performance to match what they think is expected of them, rather than playing the music they and their communities value most, in the way it is valued by them”.

What would this amount to in practice? The description might easily evoke cartoonesque images of local village heads, quickly taking action to dress up their local performers in fancy costumes and push musicians onto a stage, while adding all sorts of “extras”, synthesisers, guitars, amplification, light shows, anything that might enhance the chance of their genre being elected as ICH. After all, it could trigger financial support. One can easily also imagine the musicians themselves taking such steps. Unfortunately, this is not comic fantasy, but a plain reality. Fieldworkers in China have reported many instances of overnight transformations of traditional genres. At times they offer a rather bleak panorama of local ICH projects. Such projects, though intended to support and reinforce centuries-old local heritages, may actually distort or destroy them.

For instance, Frank summarises Gao Inga’s discussion of a group of local puppeteers in Huayin, Shaanxi:

The local authorities told them to do away with their shadow screens and shadow puppets, which the officials presumably thought of as old-fashioned or dull. Instead, the players (who had been a “sitting’”band as shadow puppeteers) were now requested to dance to music on stage, initially music from their own repertoire, but soon new music was added, infused with bass, keyboard and other pop instruments. All of these alterations were decided and directed by a local official, who was not part of the original crew.

It’s fine if local performers take autonomous decisions to modernize their own shows, but if government officials apply the ICH label to justify a complete facelift of a rural genre, as happened in Huayin, it becomes questionable. Even if the performers in this case seemed to be happy in their new roles, and with the regular incomes now allotted to them, one cannot help but judge this as a form of destruction. The case was in no way unique. Several of us have come across similar incidences of local shadow theatre cultures being destroyed by local authorities on the pretext of “developing” and “sustaining” them.