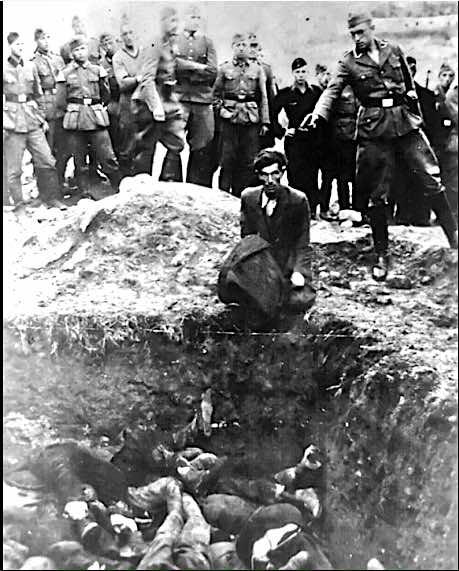

Leaders at the front of the march. Source.

Following the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on 28th August 1963, the United States Information Agency (USIA) broadcast a “Hollywood roundtable” (useful summary here), with Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston [hmm], * Sidney Poitier, Joseph Mankiewicz, James Baldwin, and moderator David Schoenbrun:

As a commentary observes:

The Hollywood Roundtable did not portray the United States as a perfect nation. Instead, the USIA used honesty and humility in an attempt to relate to foreign audiences. Throughout the film, the celebrities emphasised the nation’s faults while still promoting American values. Writer and director Joseph Mankiewicz perhaps put this best: “This is the only country in the Western world where this [the march] is possible, but also the only country where this is necessary.” (11.45)

The emphasis on hope and potential is another theme meant to lure foreign viewers to the American way of life. James Baldwin states, “No matter how bitter I become I always believed in the potential of this country. For the first time in our history, the nation has shown signs of dealing with this central problem.” (18.58)

When word spread that the government was broadcasting images of domestic inequality to foreign nations, many Americans were not pleased with USIA officials. Shortly after, Edward R. Murrow stepped down as USIA president and was replaced by Carl Rowan. At the time, this made Rowan the highest ranked African American in public office.

That such an articulate, enlightened debate was aired at the time seems all the more impressive today, with the media perilously dumbed down and Republicans renewing their energies in assaulting the rights of minorities and women. The March was a predecessor of later demonstrations leading up to those for George Floyd and for womens’ rights. Here’s a film of the March itself:

As Michael Thelwell of SNCC commented:

So it happened that Negro students from the South, some of whom still had unhealed bruises from the electric cattle prods which Southern police used to break up demonstrations, were recorded for the screens of the world portraying “American Democracy at Work”.

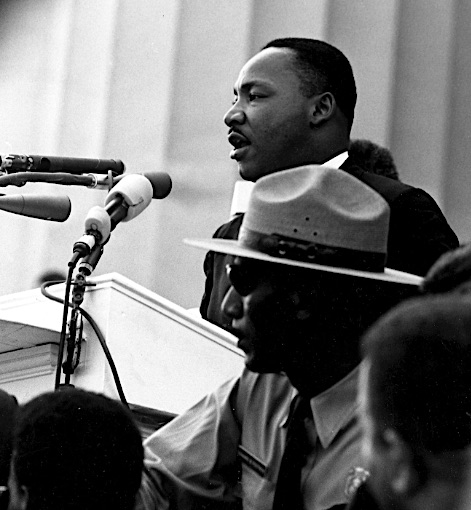

As in the Roundtable, women were conspicuously absent as speakers at the March. Gloria Richardson, Rosa Parks, and Lena Horne were escorted away from the podium before Martin Luther King’s speech. Women who were allowed to sing included Marian Anderson and Joan Baez; and here’s Mahalia Jackson singing How I got over and I’ve been buked and I’ve been scorned:

Martin Luther King delivering his I Have a Dream speech at the March.

For the tragic end of Martin Luther King, see Memphis 1968.

* The wiki article on Heston (under “Political views”) has a summary of his later conversion to racism and the NRA, ranting against Political Correctness.

I may relish the anguish (aka “posturing, self-pitying machismo”) of the slower

I may relish the anguish (aka “posturing, self-pitying machismo”) of the slower