This is an extraordinary book:

- Tsering Woeser, Forbidden memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution (2020).

It’s a thoughtfully-revised version of the Chinese edition, first published in Taiwan in 2006 (Weise 唯色, Shajie 杀劫). The English text results from the effective team work of Woeser, editor Robert Barnett, and translator Susan T. Chen.

Forbidden memory contains some three hundred images, mostly photos taken by Woeser’s father Tsering Dorje at the height of the Cultural Revolution from 1966–68, complemented by her own illuminating comments and detailed essays. While the focus is on the first two years of extreme violence, the book is not merely the record of a brief aberration: it contains rich detail both on the previous period and the situation since the end of the Cultural Revolution, as Woeser pursues the story right through to the 21st century. Using her father’s old camera, she went on take photos of the same locations in Lhasa in 2012. Some of the material also appears on the High Peaks Pure Earth website (links here and here).

Tsering Dorje (1937–91) was born in Kham to a Chinese father and a Tibetan mother. In 1950, aged 13, he was recruited to the PLA on their push towards Lhasa. By the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution he was a mid-ranking PLA officer, working in a military propaganda unit as a photographer. [1] In 1970 he was purged, transferred to a post in the People’s Armed Forces Department in Tawu county in his native Kham, 600 miles east of Lhasa. He returned to Lhasa in 1990, serving as a deputy commander of the Lhasa Military Subdistrict under the Tibet Military District, but died there the following year, still only in his mid-fifties.

His daughter Woeser was born in Lhasa in 1966; while her first language as a child was Tibetan, she received a Chinese education, and writes in Chinese. Having graduated from university in Chengdu, she worked as a reporter and editor while writing poetry. Through the 1990s she became increasingly sensitive to the plight of the Tibetan people, and though working under severe limitations, she has managed to keep publishing. [2] As the book’s Introduction comments, while she is openly critical of China’s policies in Tibet,

many of the issues that she raises, at least in this book, are criticisms of China’s cultural policies in Tibet rather than its claim to sovereignty.

Most of the book’s images come from Lhasa—which, of course, doesn’t represent the wider fate of Tibetans in the “Tibetan Autonomous Region” (TAR), Amdo, and Kham (covering large areas of the Chinese provinces of Gansu and Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan respectively), all deeply scarred by the Chinese takeover.

Introduction

After a Foreword by Wang Lixiong, Robert Barnett, most lucid and forensic of scholars on modern Tibet, provides a substantial introduction.

The “grotesque forms of humiliation and violence” presented in the book are a forbidden memory indeed. Explaining the importance of the images in the book, Barnett notes that most of the information previously available was based on the accounts of “new arrivals” into exile since the 1980s, some of whom published accounts of their experiences during the Cultural Revolution—

Yet most of these writers had been in prison throughout the Cultural Revolution years and so had seen little of what took place on streets or in homes beyond the prison walls, events which in certain ways were worse outside the prison than in. And no one outside Tibet had seen photographs of revolutionary violence and destruction there.

For China as for Tibet, several scholars note that it’s misleading to take the Cultural Revolution as a shorthand for the whole troubled three decades of Maoism—as if those years of extreme violence were a momentary aberration in an otherwise tranquil period. Barnett gives a useful historical summary of China’s involvement with Tibet—before the 1950 invasion, succinctly exposing the flaws in the Chinese claim for sovereignty since ancient times; the relatively benign early 1950s, and the escalating destruction from the late 50s, culminating in the 1959 escape of the Dalai Lama; widespread hardship, and the 1966 Cultural Revolution; the liberal reforms since the early 1980s, and recurrent outbreaks of unrest since. [3]

Tsering Dorje’s photos

stand as artworks in their own right and as exceptional sources or provocateurs of knowledge. That is, they tell us not only information about the images they contain, but, like any work of art, point to moral and philosophical questions that go to the heart of the Chinese socialist attempt to construct or reconstruct Tibetan history and modernity. Woeser points to many of these issues in her comments—Which of these pictures were posed for the photographer? What were the participants really thinking but could not show? And, necessarily of special urgency for her, what did her father really feel about the often brutal and unprecedented events he was capturing with his camera?

So why did Woeser’s father take these photos? She wonders if it was to resist forgetting. It was clearly not to expose abuses; nor merely because he was a keen photographer. Barnett is always attuned to visual images and their messages (and we should all learn from his former courses at Columbia, here and here; see also §§11 and 12 of Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy’s fine bibliography on the performing arts in Tibet). He points to two images (figs.9 and 21) where we see individuals who appear disengaged from the central action.

The aesthetic precision of these photographs itself provokes the question as to what is outside the borders of the image. For example, where are the Chinese? […] Were they just outside the frame, did they inform and shape those actions in some way from afar, had Tibetan activists by that time learnt to initiate and run these actions without them, or had Tibetan culture changed so as to incorporate and naturalize such actions? […]

All of Tsering Dorje’s photographs have this bivocal quality, telling two stories at the same time, and leaving Woeser unable to resolve her fundamental question about how her father viewed the events that he turned into lyrical images of socialist achievement. [4]

Barnett makes another important point:

She is clearly an engaged and committed writer, but, read carefully, she appears to be arguing almost the opposite of the conventional advocate for Tibet or the typical opponent of the socialist project. Clearly, she is appalled at what was done in the name of that creed, both to the individuals involved and to the nation and the culture that were its targets. But she is unusually careful to avoid saying that Tibetans had no responsibility for the atrocities that occurred. She does not remove the moral burden from their new rulers or avoid the unstated but obvious implication that Chinese rule involved unusually oppressive domination. But neither does she lift the moral burden from Tibetan participants or depict them, as is done in much of the writing on this topic by foreigners and exiles, as victims only: they are participants in the events that she describes, involved in very complex situations, which might or might not be in some way of their own making. Indeed, at least twice she makes the point that in certain issues during this period (such as adherence to one or other faction) ethnicity was not a factor. This already distances her from more simplistic polemics on this topic.

But she goes further than that: she also declines to say that Tibetans shown as happy in these photographs were always faking that emotion. She has no reluctance in stating that in many cases, particularly at the outset of the Chinese arrival in Tibet, ordinary Tibetans welcomed reforms and social changes at that time. As far as one can tell, she is not criticizing socialism as such, or even land reform and radical social redistribution. Her criticism is of the barbarities—cultural, historic, and cognitive as well as physical—that occurred as the socialist project in Tibet progressed. She presents a strongly critical perspective toward China’s record in Tibet and its social experimentation there, but much of her effort is not so much the chronicling of abuse as an attempt to understand what led people to become involved in their perpetration. “Why,” Woeser asks of the unknown woman hacking golden finials on the roof of the Jokhang temple, “did she seemingly believe that turning the past to ruins would give birth to a bright new world?”. The question remains unanswered, but, like so many of these photographs and their captions, it challenges us to try to understand the ideological constructions of the time that made such actions seem natural and even necessary to so many participants, both the rulers and the ruled.

These distinctions, undeclared though they are, are important ones, because we can imagine that they could have offered some common ground between her and her father, the search for which is clearly the underlying project of Forbidden Memory. In that sense, Woeser’s work is not just about exploring through the criticism of excess the possibilities for reconciliation between herself and her father, but also about searching for a shared space between herself, a person brought up as Chinese, and China, a nation that has chosen to forget much of what was excessive and abusive in its past and its treatment of Tibetans. As such, Woeser’s appeal to remember a painful history can also be seen as an unstated suggestion that the acknowledgement of previous abuse and suffering could offer a route toward potential reconciliation between the Tibetan people and the state of which they are now a part. Her father’s photographs cannot in themselves change political history or reshape the future, but, her work seems to suggest, they can open up a discussion and perhaps even a healing of the underlying wounds and pain that have marked Tibet’s calamitous encounter with China since the 1950s.

The galleries

The images are presented in eleven galleries under five headings. In describing the scenes, Woeser’s own illuminating comments amount to a detailed chronicle of the whole period. Far from an impersonal panorama of suffering, she attempts to identify the people shown in the photos, both victims and their tormentors, often seeking them out many years later. And she refers to the succession of incidents since the reform era.

The first group of galleries is headed “Smash the old Tibet! The Cultural Revolution arrives”. The first photos are from 1964, five years after the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. In these images

traditional ways of life are still evident—we see monks, former aristocrats, and religious ceremonies that appear to be functioning normally. Their focus, however, is on the excitement of socialist construction.

- Gallery 1, “On the eve of the storm”

Fig.6: A debating session during the Monlam Chenmo festival, 1964.

- Gallery 2, “The sacking of the Jokhang”. Wondering “Who is to be blamed?”, Woeser later interviewed several participants and eyewitnesses, going on to pursue the later history of the Jokhang..

According to one source, over 2,700 monasteries were active in TAR [NB] before 1959, 550 by 1966; by 1976 only eight were still standing.

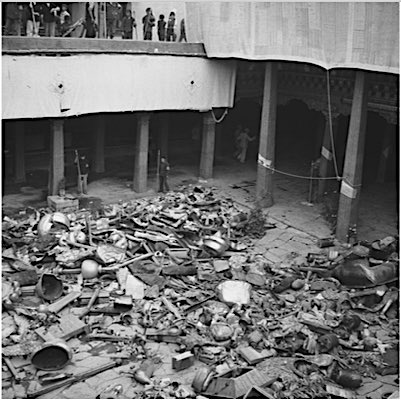

Fig.35: The Great Courtyard in the Jokhang immediately after the “revolutionary action” of August 24, 1966.

Woeser’s text:

The courtyard had traditionally been used for monks attending the annual Monlam Chenmo. Those from Drepung Monastery would sit in the middle while those from other monasteries would sit in the cloisters and in the gallery. The Dalai Lama would come down from the Sun Chamber, the viewing chamber that looked down on the courtyard from the upper floor, to take part in the prayer gathering, seated on a golden throne on the left side of the courtyard.

It was in this courtyard that armed police beat and arrested scores of monks during the Monlam Chenmo of 1988. Long queues still form there during religious festivals when pilgrims come to the temple from all over Tibet, but increasing restrictions by the authorities mean the privately sponsored ceremonies once held there now rarely if ever occur.

- Gallery 3 “Denouncing the ox-demon-snake-spirits”. We now move on to the human targets of the destruction. As Woeser comments:

Some were religious figures, statesmen, or military officers of the Tibetan government prior to the 1950s; others were merchants, landlords who owned rural estates, or managers working for those landlords. They were denounced and humiliated in mass assemblies, struggle parades, and smaller struggle sessions organized by various Neighborhood Committees. […]

The outcomes for some of those in these photographs were insanity, illness, or death. Some of them died back then, others passed away in the years after the Cultural Revolution was over. Not many of them are still around. Among the survivors, some have gone abroad, while those who have stayed put have been awarded new roles: they became “United Front personages,” with paid positions in the TAR Political Consultative Conference, the People’s Congress, or the local branch of the Buddhist Association. Once appointed, for the sake of self-protection, they all have to serve as décor for the state and as mouthpieces for its policies.

As ever, Woeser goes to great lengths to identify the people in the photos.

Fig.58: the Tenth Demo Rinpoche paraded with his wife. From a major lineage of reincarnated lamas, he was also the first photographer in Tibet—the camera slung around his neck was meant as “criminal evidence” of his foreign connections and his nature as a reactionary element.

In fig.66, a former aristocrat-official has been made to carry a case of gleaming knives and forks, probably to show “that he was a member of the exploiting class, living a life of luxury and corruption”, and perhaps that the family was close to Westerners—evidence of treason.

A series of images (figs.67–75) show the parading of Dorje Phagmo, best-known of the female trulku reincarnate lamas in Tibet.

Fig.68: Dorje Phagmo, flanked by her parents.

She had been hailed across China as a “patriot,” having returned to Tibet soon after following the Dalai Lama into exile in 1959; she had even been received by Mao in Beijing, and back in Lhasa was granted high official positions. And after the end of the Cultural Revolution she was again given government posts, often appearing in TV reports of official meetings.

In Fig.85 the involvement of Woeser’s father in the events becomes even more disturbing:

The photograph captures a moment when Pelshi Po-la, staring without expression at the camera lens, must have momentarily exchanged eye contact with the PLA official behind the view finder of the camera: my father.

The reflections prompted by such images almost recall representations of the Crucifixion.

This gallery concludes with fine essays on “ox-demons-snake-spirits”; the diversification of activists as they manufactured “class struggle”:

a considerable number of activists pivoted dramatically to religion after the Cultural Revolution was over. […] It was often said that these people’s passion in embracing religion was as intense as the zeal they had previously displayed in destroying it.

and “Rule by intimidation: life under the neighbourhood committees”.

- Gallery 4, “Changing names”—streets, stores, villages, people. As Woeser’s mother explained to her:

Back then [in my work unit], we were all required to change our names, we were told that our Tibetan names were tainted by feudal superstition and were therefore signs of the Four Olds. So we were to change both our given names and our family names. For me and my coworkers in the [school of the] TAR Public Security Bureau, when we handed in our applications for our names to be changed, they were all processed within the Bureau. You could choose which name you wanted to change to, but it had to be approved by the Bureau’s Political Affairs Office. Usually everyone chose Mao or Lin as their new family name. Or some chose to be named Gao Yuanhong, which meant “Red Plateau.” My first choice was Mao Weihua, meaning “one from a Mao family who protects China,” but that name had already been taken by someone else in the Bureau. So then I thought that since Yudrön sounds similar to the Chinese name Yuzhen, maybe I could be called Lin Yuzhen, and that would mean I could have the same family name as Marshal Lin.

We were all told to use our new names. But except for those times when representatives from the Military Region did the head count before each military drill session held in the Bureau, no one actually used these names. Many people forgot their Chinese names. One of my colleagues, Little Dawa, was also Gao Yuanhong. But every time the name Gao Yuanhong was called during the head count, she missed it. We had to poke her—“Dawa-la, they’re calling you”—and then she’d shout out, “I’m here, I’m here, I’m here!” in a rush. Now when I think of it, it was really funny.

The second group of galleries has the theme “Civil War among the Rebels: ‘whom to trust—the faction decides!’ ”

- Gallery 5. Here the theme is the violent civil war broke out between the two main rebel factions Gyenlog and Nyamdrel in 1967, with the military playing a disturbing role. “Although the two groups were bitterly opposed to each other, their aims and methods were almost indistinguishable.”

Violence continued into 1969 throughout most of the TAR—including the Nyemo uprising, on which Woeser provides further material.

The following galleries move away from Lhasa. The third group is headed “The dragon takes charge: the People’s Liberation Army in Tibet”:

- Gallery 6: the PLA in Tibet

Woeser’s father was a deputy regimental officer in the Tibet Military Region during the early phase of the Cultural Revolution; after the Tibet Military Control Commission was established, he was assigned to its propaganda team. As Woeser’s mother explains, he was a firm supporter of the Nyamdrel faction. He was purged in 1970, transferred to a post in Tawu county in Kham. - Gallery 7: the Tibetan militia.

In Tawu, Woeser’s father was responsible for training the militia. As Woeser notes, his photos were now staged rather than shots of action taken in real time, lacking the immediacy and authenticity of his earlier Lhasa photographs. By now the images come more often from other sources.

The fourth group, “Mao’s new Tibet”, includes

- Gallery 8: the Revolutionary committees from 1968. As ever, Woeser gives detailed accounts. Violence and destruction continued, including the destruction of Ganden monastery. But religious activities resumed from 1972, gradually and discreetly.

- Gallery 9, “The people’s communes”. Here Woeser describes the adverse effects of the establishment of people’s communes with yet another fine essay. The communes were only set up in TAR from 1965, much later than in mainland China. Woeser notes again that her father’s photos did not capture the heavy repercussions of communalisation in many of the farming and nomadic areas of Tibet.

After he had witnessed and documented those terrible scenes of monasteries being wrecked, statues of the Buddha being destroyed, and Buddhist texts being burned in their thousands, did he really believe in the new era of Tibetan rural happiness that he tried to capture with his camera? I still struggle with this question.

- Gallery 10, “Installing a new god”, Chairman Mao—again mainly illustrated with sanitised propaganda images.

The final group, “Coda: the wheel turns”:

- Gallery 11: the karmic cycle. This brief section on the reform era is based on the experiences of Jampa Rinchen (see below).

Those who had been ox-demon-snake-spirits in the previous cycle were now wheeled out once again into the political arena, this time in their function as “political flower vases” […] Ordinary Tibetans picked up their rosaries and prayer wheels and reentered the shells of ruined and half-restored temples to resume the worship of the Buddha.

Postscript

46 years later, Woeser used her father’s old camera in 2012–13 to revisit some of the scenes in his photos, now mostly using colour film. At yet another sensitive moment, following the 2008 protests and as self-immolations spread to TAR, she was under surveillance.

Trying to retrace his footsteps in Lhasa so many years later was anyway confusing and difficult. There was almost nothing that I could see in front of me that was shown in the photographs he had taken. It was as if that which should be remembered had all been removed.

Chinese tourists have replaced Red Guards, but security cameras, metal detectors, and police booths are now very much in evidence—as well as new propaganda. In the book Woeser sometimes contrasts old and new images. Still, she managed to find many traces of the past.

I tried to adopt the same camera angles, focal length, and exposure that my father had used, and to imagine what he might have felt, but the attempt to make his camera work again taught me what the more advanced technology could not replace: the immediate realities his camera captured, the changes that have happened since then, and the complexities rooted in human intention. […]

An Appendix reproduces from Tibet remembers the testimony of Jampa Rinchen, whose recollections have featured in various episodes of the book. A former monk at Drepung Monastery, he had become a Red Guard, and then a member of the militia and the Gyenlog faction. In 1986 he volunteered to serve as a cleaner at the Jokhang temple (right: helping monks at the Jokhang fashion sculptures out of tsampa and butter to be offered to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas). As he reflected sadly to Woeser in 2003,

An Appendix reproduces from Tibet remembers the testimony of Jampa Rinchen, whose recollections have featured in various episodes of the book. A former monk at Drepung Monastery, he had become a Red Guard, and then a member of the militia and the Gyenlog faction. In 1986 he volunteered to serve as a cleaner at the Jokhang temple (right: helping monks at the Jokhang fashion sculptures out of tsampa and butter to be offered to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas). As he reflected sadly to Woeser in 2003,

I destroyed a stupa. It’s no longer proper for me to wear monks’ robes.

But on the night he died,

all the monks from the Jokhang chanted for him. They prayed for him again in the evening when his body was sent for sky burial. These can be said to be the best arrangements that could have been made for him. Yet he had been unable to wear the robes again that had meant so much to him, that had symbolized for him the purity of monastic life, and that had marked the greatest loss in his life.

* * *

Again, it’s worth reminding ourselves that Lhasa and TAR don’t represent the whole story for Tibetan peoples; our studies should also include Amdo and Kham. Amdo in particular has been the focus of several fine recent works by scholars such as Charlene Makley and Benno Weiner. Alongside the recent escalation in the repression of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, we should never forget the Tibetans. And meanwhile in China, academic freedom is increasingly constricted.

Less melodramatic than many Chinese memoirs of the Cultural Revolution, this distressing, nuanced book makes a template not just for Tibet, and China, but (as Yu Jie observes in this review) for many regions of the world where victims and persecutors have to come to terms with a traumatic past.

Note also Tibet: conflicting memories, and Lhasa: streets with memories.

[1] Tsering Dorje had been sent to take photos during the Sino-Indian War in 1962; and as early as 1956, to document the Lhoba people, perhaps the smallest of the many ethnic minorities in the region—images I’d love to see. En passant, you can hear some audio recordings of Lhoba folk-songs on CD 6 of Mao Jizeng’s anthology Xizang yinyue jishi 西藏音樂紀實 (Wind records, 1994).

[2] For Ian Johnson’s 2014 interviews with Woeser and Wang Lixiong, see here and here; cf. Woeser on the recent wave of self-immolations (also the main theme of Eat the Buddha).

[3] Tsering Shakya, The dragon in the land of snows (1999) is a masterly, balanced single-volume history of modern Tibet, besides the ongoing multi-volume work of Melvyn Goldstein.

[4] Within the much larger image database for the Cultural Revolution in China, note Li Zhensheng’s photos from Heilongjiang, Red-color news soldier: a Chinese photographer’s odyssey through the Cultural Revolution (2003).

Pingback: The Cultural Revolution in Tibet | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Cultural revolutions | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Cheremis, Chuvash—and Tibetans | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Labrang 1: representing Tibetan ritual culture | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Labrang 2: the violence of liberation | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: How *not* to describe 1950s’ Tibet | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Women in Tibetan expressive culture | Stephen Jones: a blog