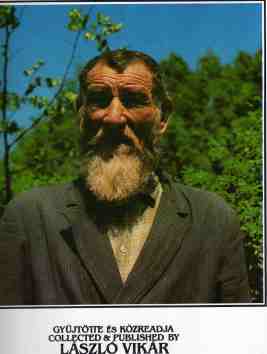

Photo: Cheremis “pagan” ritual singer H.H. Musztafa (then 69), June 1975.

Along with from the many Hungaroton LP box-sets of the musics of east Europe, another impressive 3-disc set that I brought back from Budapest is

collected and published by László Vikár (1929–2017) and linguist Gábor Bereczki. The set documents musical traditions of peoples in the “autonomous” republics around the eastern perimeter of the European part of the USSR, the central Volga and Urals—peoples about whom I know nothing, but feel we should know:

Mordvinians, Votyaks (Udmurt), Cheremis (Mari), and the Turkic-speaking Chuvash, Tatars, and Bashkirs.

Source: reddit.com.

Between 1958 and 1979 Vikár and Bereczki made four long summer fieldtrips to some 286 villages, accompanied by local scholars. With sound engineer Pál Sztanó they recorded life-cycle and calendrical items, both vocal and instrumental, including bridal dirges, funeral laments, dance tunes, and historical epics.

The recordings on this box set are part of a much larger archive. Some tracks appear on YouTube, such as

Note also this channel.

The 43-page booklet contains detailed notes, as well as maps, translations, photos, and some transcriptions.

A page from the booklet, on Mari singing.

Bartók, Kodály, and Bence Szabolcsi had already shown an interest in these groups, mainly as part of their comparative musical paleography, classifying melodic types; Vikár was building on this tradition. [2]

Such early recordings were made on request, not—as ethnographers later also sought—while documenting the social events of which they are the core. So we meet the typical issue that often crops up in Chinese collections: were they performing items then still in use, or recalling them from an earlier social practice?

And of course these projects could barely hint at the painful recent histories of such peoples (cf. The whisperers). Music is never autonomous, but gives us a window into the study of changing local societies.

Indeed, it’s worth recalling what else was happening in those years. Notwithstanding the interest of early east European music scholars in “archaic layers”, these are not timeless idyllic communities; though by the 1970s they had weathered the worst of the years of repression under Stalin, they had been constantly starved, deported, subject to political whims, suffering under collectivization and the Great Purge (cf. Blind minstrels of Ukraine, under “Other minorities”). This too is a rich field of research—see e.g.

- Andrej Kotljarchuk and Olle Sundström (eds.), Ethnic and religious minorities in Stalin’s Soviet Union: new dimensions of research (2017), in particular

ch.6 by Eva Toulouze, “A long great ethnic terror in the Volga region: a war before the war”.

See also The Kazakh famine, and (still earlier) Hašek’s adventures in Soviet Tatarstan.

The task of modern ethnographers—just as for China—is to integrate socio-political histories with expressive cultures. In 1975 the moment had still not come to record the memoirs of “pagan” Mr Musztafa—and now it’s too late.

In addition to the Garland encyclopedia of world music, for more on early collecting, see under

- Margarita Mazo, “Russia, the USSR and the Baltic states”, in Ethnomusicology: historical and regional studies (The New Grove handbooks in music, 1993), pp.197–211,

and in the same volume,

- Theodore Levin, “Western central Asia and the Caucasus”, pp.300–305.

In the early years after the crushing of the 1956 Budapest uprising, one might wonder how smooth was the collaboration between Hungarian and Soviet scholars—only of course both would have suffered under the policies of their regimes.

* * *

Left to right: Yang Yinliu, Bence Szabolcsi, Li Yuanqing, Beijing 1955.

Meanwhile in China, scholars were also documenting local traditions, for both the Han majority and the many ethnic groups—under testing conditions, and with a similar caution in broaching socio-political issues. By the 1950s, with a growing interest in early connections between Hungarian and Chinese musics, China was open to Hungarian musicology; Bence Szabolcsi visited the great Yang Yinliu in Beijing in 1955, on the eve of the Budapest uprising. And Yang Yinliu visited the USSR in 1957, just after his remarkable fieldtrip to Hunan—just before the Anti-Rightist campaign and Great Leap Backward led to untold suffering.

Yang Yinliu (seated, right) on a visit to the USSR, 1957.

For Czech–Chinese exchanges over the period, see here.

Kodály’s Folk music of Hungary, dating from 1935, was published in 1964 in a Chinese translation from the 1956 German edition—just as a brief lull after the Leap was destroyed by the Four Cleanups and Cultural Revolution.

In east Europe, the USSR, and Maoist China, the enthusiasm of ethnographic collectors of the day is admirable—even as their leaders were imprisoning them and manipulating the peoples they were studying. As William Noll observes, such studies need both to be intepreted in their historical framework and updated constantly, both by augmenting the earlier material and by documenting more recent change. Also in that post, note Noll’s comment that ethnographers of one cultural heritage commonly conduct fieldwork among peoples of a different cultural heritage—even if both groups live within the political boundaries of one state.

Left: Tibetan monks lay down their arms, 1959 (AFP/Getty.).

Right: Norbulingka, Lhasa 1966 (from Forbidden memory—essential reading).

A flagrant instance of circumspection is fieldwork by Chinese musicologists in Tibet in the 1950s, rosily portraying the region (like Xinjiang) as a happy land of singing and dancing—even in 1956 Lhasa, just as mass rebellions were breaking out all over Tibet against Chinese occupation. Two of the most distinguished, and well-meaning, Chinese scholars resumed their fieldwork upon the 1980s’ reforms, encouraging their Tibetan pupils; but the whole social-political backdrop remained taboo (see Labrang 1). See also Recent posts on Tibet.

Expressive culture is an illuminating window on society. How little we know about the world…

[1] The term Finno-Ugric seems somewhat dated, but see here for a more extensive list of peoples.

[2] An early curiosity among the ouevre of the great Bruno Nettl is his slim tome Cheremis musical styles (1960), part of a Cheremis project at Indiana. The Preface by Thomas Sebeok has a useful summary of interest among Hungarian and other scholars. But written from a distance, the monograph could still only be narrowly musical—free of ethnomusicology’s later concern for society and culture, in which Nettl has played such a major role; and the material that he assembles consists largely of transcriptions rather than recordings.

For Chuvash and Mordvins, note also the 1996 Auvidis CD Chants de la Volga: musique traditionnelle de Tchouvachie et Mordovie.

Pingback: Musical cultures of east Europe | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: New tag: Iron Curtain | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Another everyday story of country folk | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Guide to another year’s blogging | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The soundscape of Nordic noir | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A Czech couple in 1950s’ Tianqiao | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Alexei Sayle | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The shock of the new | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Hequ 1953: collecting folk-song | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Lives in Stalin’s Russia | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Life behind the Iron Curtain: a roundup | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The Kazakh famine | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Famine: Ukraine and China | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Chinese-Russian Muslims: the Dungan people | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Sister drum | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: How *not* to describe 1950s’ Tibet | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: The genius of Sergei Parajanov | Stephen Jones: a blog