“There is singing everywhere in Tibet”

Discuss…

Tibetan monks laying down their arms, 1959. AFP/Getty.

Tibetan monks laying down their arms, 1959. AFP/Getty.

In my first post on Labrang, recalling the debate over how to represent Tibetan music in the New Grove dictionary, I mentioned a succinct, nay flimsy, article by

- Mao Jizeng 毛繼增, “Xizang wuchu bushi ge: minzu yinyue caifang zhaji” 西藏無处不是歌——民族音乐採訪札記 [There is singing everywhere in Tibet: fieldnotes on national music], Renmin yinyue 1959.5, pp.8–11 (!).

—a strong candidate for the award of Most Ironic Title Ever. [1]

* * *

Mao Jizeng’s brief article resulted from a ten-month stay in Lhasa that he made from 1956 to early 1957. He was part of a team chosen to do a field survey in Tibet, led by the distinguished Tibetologist Li Youyi 李有义 (1912–2015); Mao Jizeng (b.1932) had just been assigned to the Music Research Institute (MRI) in Beijing after graduating from Chengdu.

The team clearly set out from Beijing with the intention of covering a wide area of central Tibet (then just in the process of becoming the “Tibetan Autonomous Region”, TAR). Unrest was already common in Amdo and Kham, and the political situation there would soon deteriorate severely in the TAR; but even in 1956, as Mao Jizeng recalled in a 2007 interview, Tibetan–Chinese relations were so tense that they had to remain in Lhasa, unable to get out into the countryside. One member of the team was so scared that he soon returned to Beijing; Mao Jizeng, being young, “didn’t know what fear was”—but he still got hold of a revolver for protection, which doesn’t suggest total faith in the warm welcome of Tibetans for their Chinese friends.

Anyway, for Mao Jizeng, “everywhere” in Tibet could only mean Lhasa. However, I learn here that Li Youyi did manage to travel farther afield with a separate team of Tibetan and Chinese fieldworkers (perhaps with military back-up?); and despite incurring political criticism in the summer of 1957, he continued doing field studies in TAR and Kham right until 1961, though not on music.

At the time, Chinese music scholars knew virtually nothing of Tibetan musical cultures—or even of Han-Chinese regional traditions of such as those of Fujian. That was the point of these 1950s’ field surveys, which would later blossom with the Anthology. But even as a musical ethnography of 1956 Lhasa, Mao Jizeng’s article is seriously flawed; it could only provide a few preliminary clues.

Those field surveys among the Han Chinese were given useful clues by the local Bureaus of Culture. But although Li Youyi was bringing an official team from Beijing, it’s not clear if there was any cultural work-unit to host them in Lhasa. Such cultural initiatives as there were in Tibetan areas at the time took place under the auspices of the military Arts-work Troupes—hardly a promising start. So Mao Jizeng may have been left to his own devices. Indeed, while in my early days of fieldwork I learned a lot from home-grown cultural workers, as time went by their successors were more interested in platitudinous banquets than in local culture, and it was preferable to bypass them in favour of grassroots sources. Still, Mao Jizeng would doubtless have been quite happy working within the state system.

The MRI had entrusted him with one of their three Japanese-imported recording machines, but batteries were an intractable problem. Billeted in the Communications Office, he could hardly engage meaningfully with Lhasa folk.

Now, I’m full of admiration for all the brave efforts of music fieldworkers in Maoist China to convey useful material on traditional culture despite political pressure—but this is not one of them. In a mere four pages Mao Jizeng managed to pen a tragicomic classic in the annals of the dutiful mouthing of propaganda, obediently parroting the whole gamut of Chinese music clichés. We might regard it under the Chinese rubric of “negative teaching material” (fanmian jiaocai 反面教材).

At the same time, I try not to judge his article too harshly: we should put ourselves in his shoes (cf. feature films like The blue kite, and indeed Neil MacGregor’s question “What would we have done?”).

Han Chinese scholars, not to mention peasants, were already quite familiar with the effects of escalating collectivisation upon their own society; there too, fewer people had the time or energy to sing or observe traditional ritual proprieties. But conditions in Lhasa must have alarmed the team that arrived there in 1956. Worthy as fieldwork projects were, they could only gloss over the social upheavals of the time.

At the head of the Music Research Institute in Beijing, Yang Yinliu, his distinguished reputation based on seniority and massive erudition, had earned a certain latitude for his studies of traditional music. While paying lip-service to the political ideology of the day—elevating the music of the working masses at the expense of the exploiting classes, and purporting to decry “feudal superstition”—he somehow managed to devote just as much attention to “literati” and “religious” culture as to more popular, secular genres.

After all, ethnomusicology was only in its infancy even in the West; and despite some fine fieldwork by Chinese folklorists before the 1949 revolution, the concepts of anthropology were still barely known—still less as it might apply to musicking. David McAllester’s pioneering 1954 monograph on the Navajo makes an interesting comparison, free of glib defences of the policies of his compatriots who had usurped their land.

Of course, in reading any scholarship, one always has to bear in mind the conditions of the time—particularly when we consult documents from Maoist China (as we must). They often provide revealing details, as I’ve noted for the history of collectivisation and famine in the Yanggao county gazetteer and sources for Hunan. We have to learn to “read between the lines” (cf. my Anthology review).

The main audience for such articles was urban, educated Han Chinese, who would know no better, and were willing or constrained to go along with the pretence. Their perspectives grate only with modern readers, certainly those outside China who are equipped with more information about conditions in the PRC under Maoism than was then available. [2]

The political background

Here, while consulting Robbie Barnett’s course on modern Tibet, we should turn to the masterly, balanced

- Tsering Sakya, The dragon in the land of snows: a history of modern Tibet since 1947 (1999), chapters 5–7. [3]

In a nutshell, from 1956 the lives of Tibetans deteriorated through to the major 1959 rebellion and the Dalai Lama’s escape into exile; then by 1961 a brief respite led to still more appalling calamities after 1964.

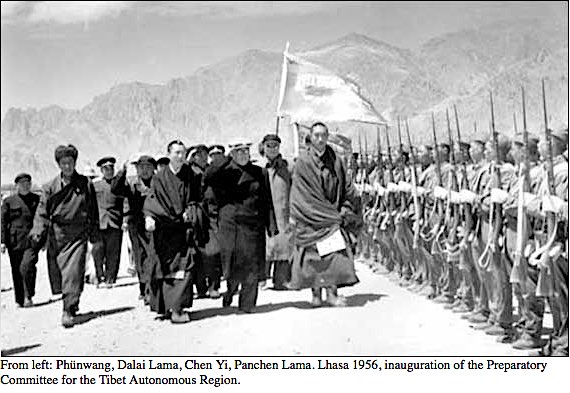

Source here.

For the first few years after the 1950 Chinese occupation, traditional life remained relatively intact. But the forming of the Preparatory Committee for the Autonomous Region of Tibet (PCART) in 1955 made Tibetans anxious that the noose was to be pulled more tightly. For central Tibet, Chairman Mao was adopting a more gradualist policy than with the Han Chinese, proceeding more cautiously with collectivisation. But in 1955 “democratic reforms”, land reform, and mutual aid groups began to be implemented in Kham and Amdo, and armed uprisings soon erupted there, prelude to the major rebellion of 1959. The Chinese responded by bombing monasteries.

Even as refugees were arriving in Lhasa from Kham and Amdo with tales of Chinese violence and assaults on religion, the city also saw an influx of Chinese labourers, troops, and cadres; anti-Chinese feeling grew. But both Tibetan and Chinese officials strove to isolate central Tibet from the unrest, and Khampa refugees found themselves unwelcome in Lhasa.

Still, opposition to Chinese rule grew in central Tibet. During the Monlam New Year’s rituals of 1956, wall posters appeared in Lhasa denouncing the Chinese and saying that they should return to China. By the end of March 1956—when Mao Jizeng must have been in Lhasa—the atmosphere there was tense.

In November, as the Western press were equating the revolts in Kham with the Budapest uprising, the Dalai Lama managed to visit India. Amidst complex diplomatic considerations (which Shakya explains with typical clarity), he eventually agreed to return to Lhasa in March 1957. There, despite the Chinese promise to postpone radical reform, he learned that the situation in Tibet had deteriorated further.

In mainland China, large-scale public rituals had already become virtually unfeasible. But in July 1957 a sumptuous Golden Throne ritual was held in Lhasa for the long life of the Dalai Lama—providing a focus for the pan-Tibetan resistance movement. And from summer 1958 to February 1959—even as monastic life was being purged in Amdo and Kham—the Dalai Lama “graduated” in Buddhist philosophy with his lengthy geshe examinations, in an opulent succession of ceremonies and processions apparently unmarred by Chinese presence:

The Khampa resistance continued, with little support from Lhasa. But events culminated at the Monlam rituals in March 1959. Amidst popular fears that the Dalai Lama (then 25) would be abducted by the Chinese, he fled to India—where he still remains in exile. Meanwhile further revolts occurred in Lhasa and further afield. Their suppression was the end of both active resistance within Tibet and the attempt to forge a co-existence between “Buddhist Tibet and Communist China”.

In 1962 the 10th Panchen Lama presented his “70,000 character petition” to Zhou Enlai. It was a major document exposing the devastation of Tibetan life wrought by Chinese rule—and the reason why he was then imprisoned for the next fifteen years. For more on Amdo and the Panchen Lamas, see here.

With whatever degree of preparation, ethnographers always walk into complex societies. Such was the maelstrom into which Mao Jizeng unwittingly plunged in search of happy Tibetan singing and dancing. While one can hardly expect to find it reflected in his work, it makes essential context for our studies.

The 1959 article

Whereas monastic Buddhism has long dominated Western research on Tibet, Mao Jizeng passed swiftly over the soundscape of the monasteries. Unrest was brewing, particularly in Kham (see e.g. here), but rituals were still held in the populous monasteries in and around Lhasa, with the revered Dalai Lama still in residence; indeed, even after his escape into exile amidst the 1959 rebellion, the monasteries were still busy in 1964, as we see in Gallery 1 of Woeser’s Forbidden memory. Despite the sensitive status of “religious music”, Yang Yinliu would have been keen to study this major aspect of the culture. But while Mao Jizeng mentions elsewhere that he attended a “large-scale” ritual at the Jokhang in 1957, the monasteries seem to have been largely outside his scope.

Dutifully praising the long history of fraternal bonds between Tibetans and Chinese, Mao Jizeng toes the Party line in his brief historical outlines of various genres. He inevitably alludes to the marriage alliance with Tang-dynasty Princess Wencheng, exhibit no.1 in China’s flimsy historical claim to sovereignty over Tibet, citing the lha-mo opera telling her story, Gyasa Balsa. But while lha-mo remained popular in Lhasa until 1959—and it’s always an enchanting spectacle—that’s his only brief reference to it; he doesn’t mention attending any performances or meeting any of the musicians. [4]

Lhamo opera at the Norbulingka. 1950s. Source: Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy (ed.), The singing mask (2001).

And these happy smiling ethnic minorities, they just can’t stop singing and dancing, eh! [5] Mao Jizeng tells how he often witnessed street gatherings with young and old singing and dancing together. And he was told a story about a Tibetan work team conscripted to build a new Lhasa airport in 1954, getting together every evening after work to sing and dance till late at night. In order “to look after their health and make sure they got enough sleep” [Yeah, right], the Chinese foremen stepped in to forbid such parties, whereupon the labourers’ mood, and their work, deteriorated; their overlords had no choice but to give way. [6]

How one would like to hear the Tibetan side of the story. Indeed, Tsering Sakya (The dragon in the land of snows, p. 136) gives a vignette from the same period:

In an attempt to reduce their expenditure, the Chinese began to ask people working on road construction to take a reduction in their pay. The Tibetan workers were urged that they should give their labour free as a contribution to the “construction of the Motherland”. Barshi, a Tibetan government official, remembered that when the people refused to accept a cut in their wages, the Chinese started to lecture them, saying that in the new Tibet everything was owned by the people, and that the wealth of the state was inseparable from the wealth of the people.

One intriguing genre that Mao Jizeng might have found suitable to record was khrom-‘gyu-r’gzhas, satirical songs lampooning prominent officials in the Old Society; but alas he doesn’t mention them. I don’t dare surmise that such songs might have been adapted to satirise their new Chinese masters. [7]

Tsering Shakya cites a more blunt street song popular in Lhasa after the Dalai Lama’s return from India in 1957:

We would rather have the Dalai Lama than Mao Tse-tung

We would rather have the Kashag than the PCART

We would rather have Buddhism than Communism

We would rather have Ten sung Mag mu [the Tibetan army] than the PLA

We would rather use our own wooden bowls than Chinese mugs.

Nangma–töshe

What Mao Jizeng did manage to study was the popular instrumental, song, and dance forms nangma and töshe, for festive entertainment—then still largely associated with elite patronage, and in decline but still not purged. Around the 1920s, in addition to the “art music” style of nangma, Lhasa musicians began adapting töshe (stod-gzhas) from dance-songs of western Tibet (“Western songs”, as Geoffrey Samuel calls them).

Open-air performance of nangma, 1956.

Though Mao Jizeng might appear to have been largely engaging in “salvage” work, the photo above shows that he also witnessed some social activity. Among the performers of nangma-töshe were Tibetan Hui Muslims—including the senior master “Amaire” 阿麦惹 (Amir?), whom Mao describes as recalling the largest repertoire of nangma pieces. But he doesn’t mention meeting Zholkhang Sonam Dargye (1922–2007), who having taken part in the Nangma’i skyid sdug association, the most renowned of such groups, went on to write authoritatively on nangma-töshe from 1980. In an instructive 2004 interview (in Chinese) Zholkhang recalls senior musicians in the group—including the leader, celebrated blind performer Ajo Namgyel (1894–1942). [8]

Left: nangma, 1940s. Right: Ajo Namgyel. Source here.

Zholkhang provides some brief details for Amir. His grandfather had been a sedan-bearer in Tibet for a Chinese official from Sichuan, and Amir himself had a Chinese name, Ma Baoshan 馬寶山. A farrier by trade, he was an accomplished instrumentalist, and had served as organiser for the Nangma’i skyid sdug association.

But rather than instructing Mao Jizeng himself, Amir introduced him to the distinguished aristocrat and litterateur Horkhang Sonam Palbar 霍康·索朗边巴 (1919–95), a patron of nangma-töshe who was to be his main informant for the genre. As Mao describes in a tribute to Horkhang, for over three months he regularly visited him at his house near the Barkhor, studying with him in the mornings before taking lunch with his family. Even in the 1990s, some Chinese collectors still clung to the dubious habit of interviewing and recording folk musicians by summoning them to cultural offices (cf. my 1987 trip to Chengde), but that probably wasn’t practicable over an extended period.

And here (inspired by the likes of Mao Jizeng to bring “class consciousness” into the discussion!) I’m pretty sure we can read between the lines again; considerations of “face” must have come into play on both sides. Amir would have made an ideal informant on nangma-töshe; but he was a common “folk artist”, perhaps living in a humble dwelling in a poor quarter—unsuitable, even dangerous, for a Chinese scholar to frequent. Whether or not he considered himself unsuitable to represent Tibetan culture to a Chinese visitor, the annual round of festivities that had long kept the musicians busy must have shrunk after 1950, and their livelihood was doubtless suffering. Like others in that milieu, Amir may have been finding it hard to adapt to the new regime, perhaps worried about the consequences of regular contact with a Chinese scholar, or simply reluctant. For Mao Jizeng to have spent more time in the folk milieu would only have exposed him to inconvenient truths that he couldn’t, and wouldn’t, document.

Conversely, Horkhang was prestigious, despite his aristocratic background. Elsewhere I learn that as a prominent official under the old Tibetan administration, he had studied English with the Tibet-based diplomat Hugh Richardson (for whose photos of the old society, see under Tibet album). Horkhang was captured by the PLA in 1950 during the battle of Chamdo (or as Mao Jizeng puts it, “the Liberation of Chamdo”). After the occupation he accommodated to Chinese rule, “turning over a new leaf” by necessity; like many former aristocrats whose status under the new regime was vulnerable, he was soon given high-sounding official titles in Lhasa, through which the Chinese sought to mask their own domination.

Horkhang’s house would have been comfortable; he still had servants. Moreover, he didn’t drink, whereas the nangma-töshe musicians had a taste for the chang beer that was supplied at parties where they performed. And it would be easier for Mao Jizeng to communicate with Horkhang than with a semi-literate folk musician. While Mao must have had help with interpreting, perhaps Horkhang had already picked up some Chinese in the course of his official duties; anyway, Mao claims that his own spoken Tibetan improved over the course of these sessions.

So in all, while Horkhang was a patron rather than a musician (cf. the mehfil aficionados of Indian raga, and narrative-singing in old Beijing), he seemed a more suitable informant for the Chinese guest. While we should indeed document the perspectives of patrons and aficionados, it should only be a supplement to working with musicians themselves. But the ideology of “becoming at one with the masses” only went so far. Given the obligatory stress on the music of the labouring classes, it may seem ironic that Mao Jizeng’s main topic was a genre patronised by the old aristocrats, and that he chose to study it with one of them rather than with a lowly “folk artist”. He justifies his studies by observing his mentor’s warm relations with the common folk. He doesn’t say, but perhaps Amir and other musicians also took part in some sessions at Horkhang’s house—in which case it would have made an ideal setting.

By contrast with the distinctive soundscapes of the monasteries and lha-mo opera, nangma’s heterophony of flute, plucked and bowed strings, and hammer dulcimer, however “authentic”, often sounds disconcertingly like Chinese silk-and-bamboo, as you can hear in this playlist— sadly not annotated, but apparently containing tracks both from exile and within the PRC:

Indeed, as with the dodar ceremonial ensemble of Amdo monasteries, the Chinese influence goes back to the 18th century. This doubtless enhanced its appeal for Mao Jizeng; and like silk-and-bamboo, it was to make nangma–töshe a suitable basis for the state song-and-dance troupes. Woeser gives short shrift to modern incarnations of nangma in her wonderful story Garpon-la’s offerings (n.9 below).

So Horkhang Sonam Palbar was Mao Jizeng’s main source for the two slim volumes that he also published in 1959,

- Xizang gudian gewu: nangma 西藏古典歌舞——囊玛 [Tibetan classical song and dance: nangma]

- Xizang minjian gewu: duixie 西藏民间歌舞——堆谢 [Tibetan folk song and dance: töshe].

Even the enlightened Music Research Institute was anxious about publishing Mao’s afterword acknowledging a Tibetan aristocrat.

According to Mao Jizeng’s 2007 tribute, Horkhang told him that he survived the Cultural Revolution relatively unscathed. This fiction may result both from people’s general reluctance to remember trauma and from the limitations of their relationship—we learn a very different story from Woeser’s Forbidden memory.

Horkhang Sonam Palbar (centre) paraded with his wife and father-in-law at a thamzing struggle-session, August 1966. Forbidden memory, fig.80.

Horkhang Sonam Palbar (centre) paraded with his wife and father-in-law at a thamzing struggle-session, August 1966. Forbidden memory, fig.80.

As Woeser explains, the Red Guards dressed him in a fur coat and hat that they found in his home, to denote his official rank in the former Tibetan government and his “dream of restoring the feudal serf system”.

Woeser goes on to describe how among the “crimes” of which Horkhang was accused was his friendship with the famous writer and scholar Gendun Chöphel (1903–51). Horkhang had helped him through times of adversity, and before Gendun Chöphel died he entrusted many of his manuscripts to Horkhang; these were now confiscated and destroyed by the activists. Still, after the end of the Cultural Revolution, Horkhang assembled what he could find of Gendun Chöphel’s work, eventually publishing a three-volume set of his writings that became an authoritative work.

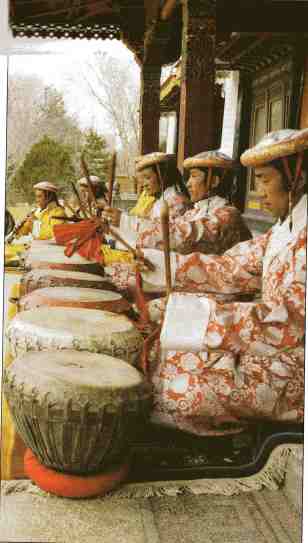

“Palace music”

By contrast with the entertainment music of nangma-töshe, in his 1959 article Mao Jizeng also gives a brief introduction to gar, the ceremonial “palace music” of the Dalai Lama. Indeed, having worked on the genre “in some depth” in the winter of 1956–57, he compiled a third monograph on it, but realised it was too sensitive a topic for publication, and it was lost during the Cultural Revolution.

Gar seems to have been in decline even before the Chinese occupation, though details on its life through the 1940s and 50s are elusive. The little section in Mao Jizeng’s article is characteristically headed “The dark system is a stumbling block to the development of music”; his main purpose here is to decry the former feudal society’s cruel exploitation of the teenage boys who served as dancers—actually an interesting angle, however tendentious Mao’s approach.

Mao Jizeng, liner notes for CD 5 of Xizang yinyue jishi (n.9 below).

Right, gar dancers, 1950s, provenance unclear.

The main instrumental ensemble for gar consisted of loud shawms and kettle-drums, of Ladakhi origin (cf. related bands in Xinjiang, Iran, and India)—formerly, at least, with the halo of a mkhar-rnga bcu-pa frame of ten pitched gongs (cf. Chinese yunluo). [9] A brief scene (from 5.50) of this silent footage from 1945 shows the gong frame on procession with two shawms:

But a subsidiary chamber instrumentation, closer to that of nangma, included the rgyud-mang dulcimer—and as a gift from the MRI, Mao Jizeng presented the musicians with a Chinese yangqin, which must have made an unwieldy part of Mao Jizeng’s luggage on the arduous journey.

He doesn’t cite a source for this section, so it’s unclear who the musicians he consulted were; the Dalai Lama, whom they served, was still in Lhasa, and by 1956 the performers were still at liberty. But following the 1959 rebellion, when the Dalai Lama had to flee, they were deported en masse to the Gormo “reform through labour” camp at Golmud in Qinghai, over a thousand kilometres distant—part of a network of such camps in the vast, desolate region (cf. China: commemorating trauma). There they were to spend over twenty years; conscripted to work on constructing the new railway and highway, singing and dancing can hardly have been part of their regime.

Mao Jizeng ends his 1959 article with a brief section on “New developments since the Peaceful Liberation [sic] of Tibet”—the formation of professional troupes, and the creation of new folk-songs in praise of Chairman Mao; also, of course, themes worthy of study. Encapsulating the fatuity of Chinese propaganda, his final formulaic paragraph is just the kind of flapdoodle we have to wade through:

With the defeat of the former local Tibetan government and the reactionary upper-class elements, traitors to their country, the great mountain weighing down on the hearts of the Tibetan people was overturned, providing more profitable conditions for the development of their ethnic music. The way ahead for Tibetan music is limitlessly broad. It will shine radiantly forth in the ranks of the music of the Chinese nationalities.

To paraphrase the immortal words of Mandy Rice-Davies only a few years later, “He would say that, wouldn’t he?”. Selflessly, I have read Mao Jizeng’s article so that you won’t have to.

Back in Beijing, and the reform era

Mao Jizeng may have largely ignored the fraught social conditions of the time, but one has to admire his persistence in remaining in Lhasa for ten months. Even by the 1990s, Chinese fieldworkers, and most foreign scholars, still tended to find brief “hit-and-run” missions more practicable, albeit over an extended period (cf. here).

Between 1956, when Mao Jizeng set off for Tibet, and the publication of his report in 1959, the political climate deteriorated severely in Beijing too. From 1957, music scholars were among countless intellectuals and cadres demoted or imprisoned during the Anti-Rightist campaign, not to be rehabilitated until the late 1970s; and the 1958 Great Leap Backward soon led to severe famine and destruction. Chinese people had to deal with their own devastating sufferings, without worrying about distant Tibet.

Even so, in 1960 Yang Yinliu managed to publish the Hunan survey that he had led, also in 1956; its 618 pages (as well as a separate study on the Confucian ritual!) make a stark contrast with the paltry material resulting from the hampered Tibetan expedition. * I wonder if his original fieldnotes have survived.

Disturbingly, the misleading clichés of Mao Jizeng’s article still continue to recur in more recent PRC scholarship. There, forty years since liberalisation, no frank reflections on the conditions of fieldwork among minority peoples in the 1950s seem to have been published—and amidst ever-tighter limits on academic freedom, such work is becoming even less likely.

Nonetheless, along with the widespread revival of tradition in the 1980s, more extensive study developed. For the major Anthology project Tibetan and Chinese cultural workers were no longer so cautious about documenting elite and religious genres. They now collected much material—with hefty volumes for TAR, Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan on folk-song, opera, narrative-singing, instrumental music, and dance. For the historian, the monographs on opera and narrative-singing (xiqu zhi 戏曲志, quyi zhi 曲艺志) are particularly useful. As with Han Chinese traditions, much of this research focused on the cultures that had been impoverished under Maoism, rather than the process of impoverishment.

From early in the 1980s, in both Dharamsala and Lhasa, gar court music was recreated under the guidance of Pa-sangs Don-grub (1918–98), the last gar-dpon master to have served under a ruling Dalai Lama in Tibet (and like Horkhang, a pupil of Gendun Chöphel), as well as the former gar-pa dancer Rigdzin Dorje. In Dharamsala it began to serve the ceremonies of the Dalai Lama again, whereas in Lhasa it was performed only in concert.

The gar-dpon, 1980s. Photo: Willie Robson.

Though we don’t know how many inmates of the Gormo camp survived, Pa-sangs Don-grub was at last able to return to Lhasa by 1982, literally scarred by two decades of hard labour. The precise timeline seems unclear, but in Woeser’s plausible interpretation, he only overcame his reluctance to accept the Chinese request for him to lead a revival of the genre when, in a brief rapprochement, he was given the opportunity to pay homage to his revered former master the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala through training performers at TIPA—and only on the Dalai Lama’s advice did he return to Lhasa to teach it there too.

The 1980s’ revival of gar. Photos: Willie Robson.

In July 1987, while I was still seeking folk ritual bands in China, the enterprising Willie Robson (with whom I later worked to bring a Buddhist group from Wutaishan to the UK) put together the Music from the Royal Courts festival at the South Bank for BBC Radio 3—a grand enterprise the like of which would hardly be possible to organise today. It included groups from Africa and India, Ottoman and Thai music, the Heike biwa epic from Japan, nanguan from Taiwan, Uyghur muqam, the Chinese qin zither—and, remarkably, a combined group from Lhasa, performing both gar and nangma-töshe.

Pa-sangs Don-grub, early 1980s; from the Chinese version of Woeser’s story.

Moved by Pa-sangs Don-grub’s 1985 book in her father’s collection, Woeser encapsulates our task in reading PRC documents:

Even a short introduction in a book can reveal a lot of information. This was the case with Songs and dances for offerings, with its brief introduction to the 14th Dalai Lama’s eleven-member dance troupe. After a few pages, only bits of information about the troupe emerged, such as the number of members and their ages. There wasn’t a lot, but at the time it probably wasn’t safe to write much more. The introduction seemed to be quite ordinary, even mediocre. Nevertheless, much information was hidden between the lines. These nuances could only be understood by another Tibetan, who would discern from just a glance what was really being said, what happened when and where. Many Tibetan readers experienced the hardship and torment the troupe endured before they had at last survived the disasters in their lives. Anyone who hasn’t experienced similar torments will find it hard to read between the lines of the writing and know what the men went through. That’s why a narrator like me is needed, who is at some distance from the incidents but is sympathetic to their reality and able to retell the story.

Also in the 1980s, Mao Jizeng’s former mentor Horkhang Sonam Palbar, having endured his own tribulations in the Cultural Revolution, was once again showered with high-ranking official titles in the Chinese apparatus—in a common pattern, serving as “décor for the state and as mouthpieces for its policies”, as Woeser observes in Forbidden memory.

Meanwhile, from 1983 Mao Jizeng was finally able to visit regions of the TAR that were out of bounds to him in 1956; and after the convulsive events of the 60s and 70s, on his trips to Lhasa he was able to meet up again with Horkhang.

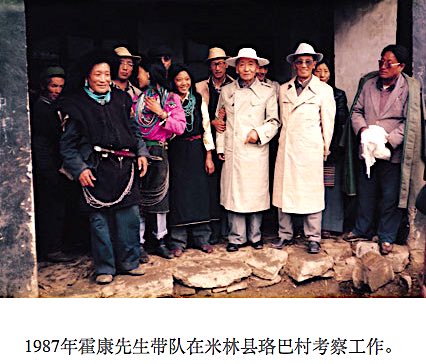

Horkhang Sonam Palbar leading a study team to a village of the Lhoba minority people,

Horkhang Sonam Palbar leading a study team to a village of the Lhoba minority people,

Mainling county, southeast TAR 1987 (cf. here, n.1).

Blissfully oblivious to all the evidence, Mao Jizeng still constantly parroted the cliché of the warm fraternal feelings between Han Chinese and Tibetans, and his own rapport with the latter, including Horkhang (for more subtle views on rapport, see the excellent Bruce Jackson; and here I develop Nigel Barley’s characterisation of the fieldworker as “harmless idiot” into “harmful idiot”).

In his 2003 tribute to Horkhang, Mao tells a story that inadvertently suggests a less rosy picture—revealing both Tibetan resentment and the insidious hierarchical power dynamics among Tibetans in their dealings with the Chinese:

In Lhasa in 1988—during yet another period of serious unrest, by the way—Mao Jizeng was having problems mustering the recalcitrant Shöl Tibetan Opera Troupe to perform Sukyi Nima for him to record. Rather shooting himself in the foot, he even lists some of their excuses: some actors hadn’t showed up, the troupe was out of money, they couldn’t find the drum… * It was only when the illustrious Horkhang stepped in to cajole them that they finally had to play ball.

And widespread unrest has continued in Tibetan areas. In 2009 the popular Amdo singer Tashi Dondhup was sentenced to fifteen months’ imprisonment after distributing songs critical of the occupation—notably 1958–2008, evoking two terrifying periods. Many other Tibetan singers have been imprisoned since 2012. [10]

* * *

As William Noll observes, the whole history of ethnomusicology abounds with scholars who come from a society that oppresses the culture in question; and around the world there are plenty of accounts of fieldwork projects that fell short of their ambition. The limitations of Mao Jizeng’s ten-month sojourn in the tense, turbulent Lhasa of 1956, and even his inability to reflect on the issues involved, may not be such an exceptional case.

As another kind of outsider, only able to read Chinese and English but not Tibetan sources, such are the slender clues that I can offer. Note also Tibet: conflicting memories, Forbidden memory, and Lhasa: streets with memories.

So much for “There is singing everywhere in Tibet”. Meretricious (and a Happy New Monlam).

With thanks to Robbie Barnett

[1] Since the present or past tense is not necessarily specified in Chinese, one might almost be tempted to read it as “There was singing everywhere in Tibet [until we barged in and broke it all up]”—or perhaps as an optative, like “Britannia rule the waves”?!).

[2] By the way, “singing” is a very broad, um, church. Both singing and dancing on stage are only the tip of the iceberg; they lead us to folk festivities, notably calendrical and life-cycle rituals. Though “revolutionary songs” were an obligatory component of Chinese collecting throughout the PRC (if anyone remembers songs of resistance sung by the Tibetan rebels from 1956, people certainly weren’t going to sing them for Chinese fieldworkers—who anyway wouldn’t want, or dare, to listen), their main interest was the traditional soundscape (cf. Bards of Shaanbei, under “Research and images”). Tibetan and Chinese pop music only came to play a major part in the Tibetan soundscape after the 1980s’ reforms.

Even today in a (Chinese) region like Shaanbei, famed for its folk-songs, it would be misleading to claim that singing is everywhere, harking back to the romantic image of Yellow earth. Sure, folk-songs are still heard quite often there, but often in rowdy restaurants rather than by shepherds on picturesque hillsides (cf. One belt, one road).

[3] For yet more detail, see Melvyn Goldstein’s multi-volume A history of modern Tibet—for this period, vol.3: The storm clouds descend, 1955–1957 and vol.4: In the eye of the storm, 1957–1959. There’s also extensive research unpacking the representation of ethnic minorities in the PRC, from Dru Gladney and Stevan Harrell and onwards. For the changing physical and mental landscape of Lhasa, note Robert Barnett’s sophisticated book Lhasa: streets with memory (2006).

[4] Naturally, Mao Jizeng rendered Tibetan terms in Chinese characters, just as Western visitors devised systems to render it in their alphabet. Later, as the variants of the Wylie system became standard for international publications, Chinese transcription was acknowledged to be inadequate—though it still works for the Chinese… I’ve tried to give Wylie versions of Mao Jizeng’s Chinese terms.

[5] For Tibetan folk-song, see §9 of Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy’s Western-language bibliography—including this detailed ethnography of a family in Amdo, yet another impressive publication from Kevin Stuart’s team; Sangye Dondhup’s list for sources in Chinese and Tibetan; and the folk-song volumes of the Anthology.

[6] The first such project is usually dated to 1956; even then, the airport didn’t become operational until 1965. Perhaps the 1954 labourers, too exhausted by singing and dancing, and too demoralised at being forbidden to do so, were unable to complete the job?

[7] See Melvyn Goldstein, “Lhasa street songs: political and social satire in traditional Tibet”, Tibet journal 7.1–2 (1982), based on material collected among exile communities. For Sitting Bull’s ingenious speech in Sioux for assembled white dignitaries, cursing them with impunity, see n.1 here.

[8] For nangma–töshe, see the bibliographies cited in n.5 above, as well as the Anthology for TAR. For the work of Geoffrey Samuel, apart from his chapter in Jamyang Norbu (ed.), Zlos-gar (1986), see “Songs of Lhasa”, Ethnomusicology 20.3 (1976)—including an Appendix referring to fifteen 78s recorded in Lhasa between 1943 and 1945 by the British Mission under Sir Basil Gould, which one would love to compare with later versions!

The writings of Zholkhang Sonam Dargye (Zhol-khang bSod-nams Dar-rgyas) feature in Sangye Dondhup’s list of Tibetan sources; he is included among the biographical entries for Tibetan musicians in the New Grove dictionary (handily assembled here; main article on Tibetan music here). For the role of female performers before 1959, see the fine article Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy, “Women in the performing arts: portraits of six contemporary singers”, pp.204–207.

In search of Ajo Namgyel, I found the fascinating article by Jamyang Norbu “The Lhasa Ripper“, on the “dark underbelly” of pre-occupation Lhasa: crime, prostitution, beggars. For nangma bars since the 1990s, see e.g. Anna Morcom, Unity and discord: music and politics in contemporary Tibet (TIN, 2004), and her “Modernity, power, and the reconstruction of dance in post-1950s Tibet”, Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 3 (2007).

[9] A useful introduction to gar before the occupation, and then from exile, is Jamyang Norbu with Tashi Dhondup, “A preliminary study of gar, the court dance and music of Tibet”, in Zlos-gar. See also Mark Trewin, “On the history and origin of ‘gar’: the court ceremonial music of Tibet”, CHIME 8 (1995). As well as the entry for Pa-sangs Don-grub in the New Grove (with a list of his publications), do read Woeser‘s story “Garpon La’s offerings“, Manoa 24.2 (2012). Dates given for the gar-pa Rigdzin Dorje differ: 1915–83 apud Zlos-gar, 1927–84 according to Grove. The mkhar-rnga bcu-pa gong-frame is mentioned in the Zlos-gar chapter and the Grove section on gar.

Within TAR the fortunes of gar are documented in the Anthology; and Mao Jizeng’s six-CD anthology of Tibetan music in TAR, Xizang yinyue jishi 西藏音樂紀實 (Wind Records, 1994), recorded since the 1980s, features both nangma-töshe (CDs 3 and 5) and gar (CD 5, ##3–4), despite the nugatory liner notes; see Mireille Helffer’s review. In the absence of Mao Jizeng’s monograph, all I can find of his notes on gar is on pp.38–42 of this trite overview of Tibetan music.

[10] For another thoughtful article by Woeser, exploring the shifting sands of prohibited “reactionary songs” and the challenge of keeping track of subtle allusions, see here.

* In another age, he might have returned with gifts emblazoned “My mate went to Lhasa and all I got was this lousy T-shirt”.

** Impertinently, this reminds me of both the Monty Python cheeseshop sketch and various instances of musos’ deviant behaviour (notably this, and even Revenge at the Prague opera).

Pingback: Two recent themes | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Cheremis, Chuvash—and Tibetans | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Labrang 1: representing Tibetan ritual culture | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Yet more Chinese clichés: music | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Two local cultural workers | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Tibet: a blind musician | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Women in Tibetan expressive culture | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Ethnic polyphony in China | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Daoism and standup | Stephen Jones: a blog – Dinesh Chandra China Story