In the melodic lines of both late romantic and popular music, upward leaps of both minor and major 7ths are common—the latter is a particularly striking expressive feature.

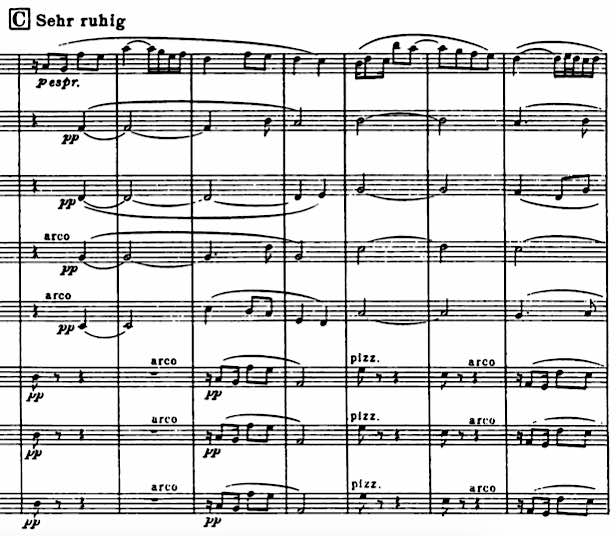

A few instances, over sumptuous harmonies: Mahler relished the interval, such as in the finale of the 9th symphony:

and

and Richard Strauss favoured it too, such as this glorious passage in Ein Heldenleben, where the massed horns hijack the recapitulation, with a repeated phrase ending in a minor 7th leap, then—amidst heady modulation—yet another one, culminating in a blazing major 7th:

Richard Strauss favoured it too, such as this glorious passage in Ein Heldenleben, where the massed horns hijack the recapitulation, with a repeated phrase ending in a minor 7th leap, then—amidst heady modulation—yet another one, culminating in a blazing major 7th:

I’ve already offered you Carlos Kleiber‘s version (with the above passage from 23.39); here’s Mengelberg and the New York Phil in 1928 (from 25.00):

And a gorgeous major 7th leap adorns the glowing string melody of the slow finale (from 35.40, in three flats):

In the Four last songs, Beim Schlafengehen is animated by the leap—as at the opening, in the gorgeous dialogue between violin and singer, and the final horn solo. Here’s the beginning of the violin solo (in five flats):

and the climax of the vocal part, with leaps of first a minor and then a major 7th:

Henry Mancini used the major 7th leap to wonderful effect in Moon river, and it’s a quirky feature of Burt Bacharach‘s Raindrops keep falling on my head:

In Dusty Springfield‘s I only want to be with you, the leap (at “Oh can’t you see”) also works beautifully.

The leap of a minor 7th can be highly expressive too, as in Billie Holiday’s extraordinary You’re my thrill.

Patsy Cline’s Crazy has some expressive intervals: the first phrase opens with a descending 6th (and then an A major arpeggio!), then the second phrase has a descending minor 7th followed by an ascending minor 7th on “crazy for feeling…”!

And I love the ascending minor 9th that opens Plus fort que nous in Un homme et une femme, leading to a sequence of ascending 7ths. The minor 9th leap pervades the 2nd movement of Mahler 5.

This tranquil interlude before the end of the 1st movement of Mahler 4 (Abbado’s performance there, from 14.30) has a succession of gorgeous leaps:

Further instances welcome…

At the other end of melodic movement, see Unpromising chromaticisms.

Meanwhile, undistracted by the harmonic element, Indian raga is a classic locus for exploring monophonic pitch relationships, mostly based on conjunct intervals…