People like Li Wenbin and He Qing perceived no conflict between worshipping the gods and supporting Mao’s broad social goals.

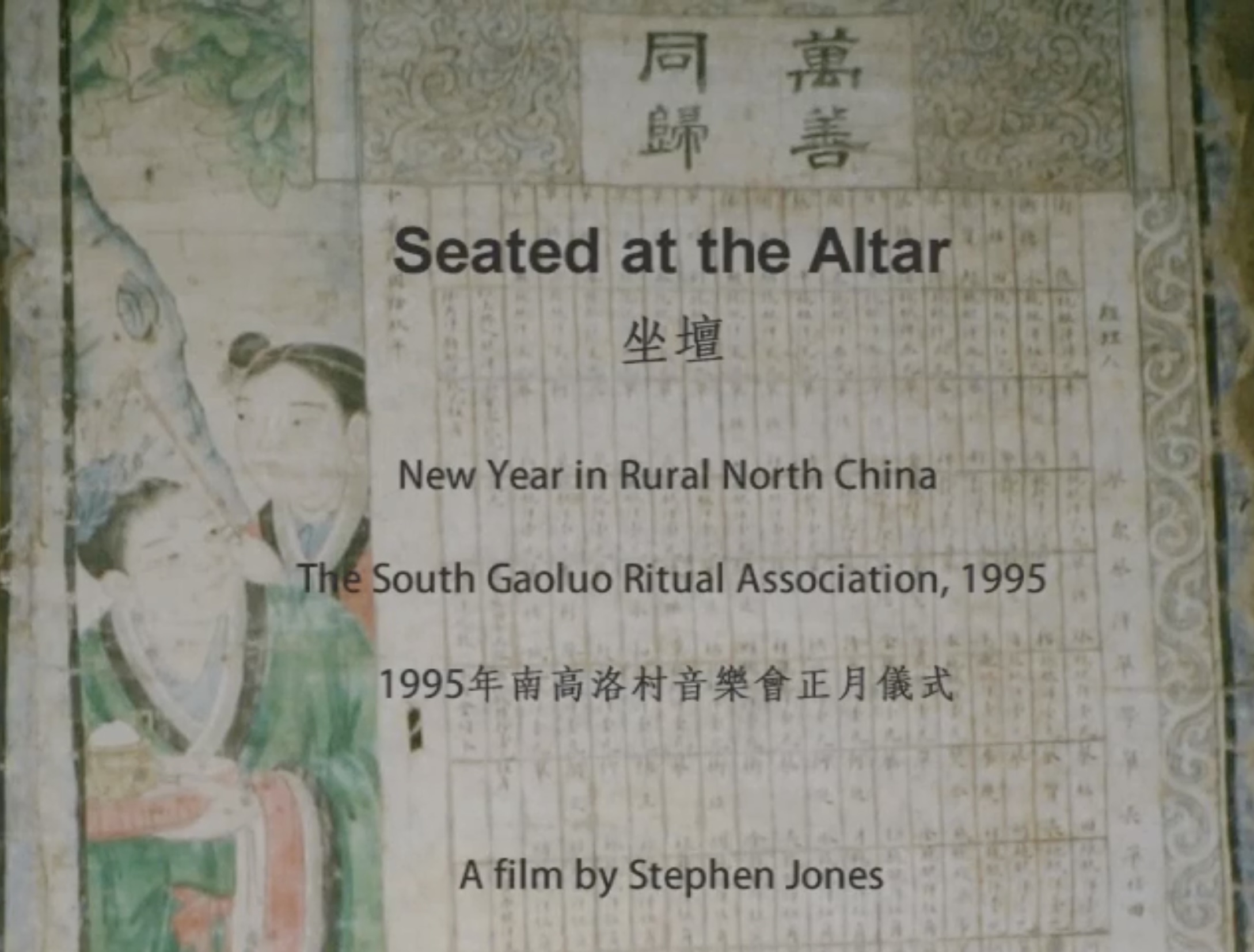

My new film on the 1995 New Year’s rituals in Gaoluo prompted a recent post on the tenacity of rural tradition. Still reflecting on my fieldwork, it’s worth revisiting my remarks in Plucking the winds (pp.277–85, with minor edits) on “belief”—referring to devotional village-wide groups like those of Gaoluo

By 1995, as throughout its history, the association had a patchwork of ritual artefacts made at various times over the last century. The previously bare and unprepossessing “public building”, once fully adorned, becomes a place of great beauty, a fitting backdrop for the association’s ritual performance. But since the 1980s’ liberalisations, unlike many villages in north and south China, and indeed nearby such as Niecun just across the river, Gaoluo has not sought to build new permanent temples.

What beliefs do such artefacts symbolise? Aside from popular belief in Houtu and the God of Prosperity, formidable He Qing, always a fine source for old traditions, said the association worships Dizang, god of the underworld, as the association is said to go back to “the Tang king’s tour of hell”. Members have often said this was a Daoist association, even that Gaoluo was a Daoist village. We must understand this in the context of a dilution of the term Dao, meaning simply ritual. The senior He Yi recalls a tradition that their [melodic instrumental] music was learned long ago from Daoists (laodao), for what it is worth; perhaps a priest attached to the temple of North Gaoluo or the temple of South village. In fact, where one can distinguish, their ritual manuals have a substantial Buddhist component, and they also claim to believe in the Buddhas (fo). Fo and Dao are often interchangeable in these villages.

Screenshot

Association members themselves do not generally worship, regarding participation in ritual activities itself as a form of worship. In fact, women are altogether more prominent as worshippers, despite being excluded from active participation in the association. Incidentally, the name “music association” (yinyuehui, see here and here) seems to be used less than terms like huitong 会统 “association” and zaijiaode 在教的 “those in the teachings”. Ritual function is paramount: in discussing the activities of the association, villagers also often talk of the scriptures, with terms like “taking out”, “escorting”, or “offering up” the scriptures (chujing 出经, songjing 送经, fengjing 奉经).

Masters of the vocal liturgy: left, Cai Yongchun; right, Li Wenbin.

As to the ritual specialists, while they practise the rituals with considerable intensity, few of them claim to “believe” deeply in the gods. This is a difficult area—my efforts to elicit insights often recall Nigel Barley’s bemusement in Cameroon. Genial Shan Yude, himself a member of the “civil altar” reciting the scriptures, recalled the previous generation frankly: “Cai Fuxiang didn’t really believe, he just learned the liturgy when he was young and got attached to it, like me; he was a Party member. Cai Yongchun believed—he didn’t join the Party.” In these cases there seemed to be a certain negative correlation between Party membership and religious faith.

But it was complex, for few sought or gained admission to the Party, but many more, including Cai Yongchun, were leading participants in the revolution. Anyway, after Cai Fuxiang’s decline, his belief in the gods, or the habit of ritual, endured, but that was not the cause of his later expulsion from the Party. And there were some people, whether Party members or not, who had no time for religious traditions at all, like Shan Yude’s own father: “He didn’t believe in any gods—he was always doing things for the Party, but he didn’t join.” But throughout the area we have found leading local Communist cadres preserving the tradition of reciting their villages’ ritual manuals. People like Li Wenbin and He Qing perceived no conflict between worshipping the gods and supporting Mao’s broad social goals. Whether or not they joined the Party, people’s commitment to the new society was just one element in their psychological make-up: there was no simple correlation between religious belief and identification with the ideals of the new society.

Shan Yude also claimed “Most people in this area aren’t so superstitious, but my grandparents’ generation was more devout.” This may be broadly true: on the Hebei plain, so near the modern ideas of Beijing, faith may have declined more over the 20th century—gradually, note, not abruptly upon Liberation—than in some more remote mountainous regions of inland central China. But again the point needs qualifying. As we saw, belief was already variable among the previous generation of ritual specialists, and continues to be so today. Cai Haizeng’s father Cai Fulü practised the rituals, but with no great commitment; but now, villagers say, Haizeng is a believer, certainly more than his father. Yude himself observed, “Cai Ran and Haizeng are more devout than me. He Qing also believed, but he had a lively mind.”

Yude even admits to not believing at all, like his father. Still, if so, then he practises the ritual with utter commitment: we should distinguish belief in gods and belief in tradition, in the morality of convention. Cai Yurun made a comment that reveals the new social tolerance: “whether villagers believe or not, it’s harmless”. Though it was only officially considered harmless after about 1980, under the Maoist climate of the previous decades private worship might have become rarer, but belief was hard to assess; after all, public rituals had persisted. Very limited scientific advances and an increasingly secular climate had only partially obviated the need for the gods, and people continued to feel vulnerable.

A facile comparison with Europe springs to mind. Regional variations in industrialisation and literacy may partly explain different levels of religious belief, but within particular societies, and between generations, the situation is uneven; north Italy may generally be less “superstitious” than south Italy, but young and old people in both regions may or may not believe. Our problem for China is to recognise variation and put the supposedly dominant control of ideology in perspective. […]

Cai Yurun pointed out: “The saying goes that when they’re folded away the god paintings are just cloth, but when they’re hung out they’re gods. Don’t pay too much attention to our bullshitting normally—as soon as we Open the Altar we’re pretty serious.”

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

On pp.304–5 I observed:

As to ordinary villagers, though there are more women than men offering incense, quite few of the people are elderly: young and middle-aged women and young men seem to be more active in this. Many pray silently to the goddess Houtu for a healthy son, or for the health of their aged parents; more generally, people pray for good luck and prosperity. One couple were offering incense for the safety of the husband, who is a driver—even for the most diehard atheist, recourse to divine help is particularly tempting on Chinese roads. The atmosphere is highly jocular as people enter the courtyard. As they go to offer incense and kowtow they look embarrassed, but then when they are actually doing it they become extremely serious. Then as they get up and dust down their trousers, they look all embarrassed again, and, avoiding meeting the gaze of all the onlookers, they leave the area, often going into the “temple”.

So in many such villages over previous decades, the driving force behind the maintenance of ritual practice seems to have become not so much “religious belief” (itself an alien term) as the “old rules” (lao guiju 老规矩) of tradition. Devotional associations provide ritual as a service for the needs of the community. Under “Note on sources” in my introduction to these groups, see also my articles “Chinese ritual music under Mao and Deng” (1999) and “Revival in crisis” (2010).

Besides groups like these, this may even apply to occupational groups of household Daoists such as the Li family in north Shanxi. With the Maoist decades followed by the assaults of popular media and migration, ritual groups in some regions (including Hebei) are now further vulnerable to the secularised commodifications of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. But it would be interesting if one could somehow compare communities further south like Fujian (see under “Elsewhere” in main Menu), where religious faith appears to be a still more pervasive catalyst for popular culture. And of course faith in the gods is still evident in the popularity of spirit mediums, pilgrimages, and so on.

See also Catherine Bell on ritual.

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

The lantern tent, New Year 1998, with new and newly-copied donors’ lists.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.

Early morning procession to the soul hall, North Xinzhuang 1995. Photo: Du Yaxiong.