Notes from Berlin, 2

In Berlin a couple of weeks ago, apart from my visit to Sachsenhausen I was keen to explore the city’s GDR history, moving on into the 1950s and beyond—the Stasi memorial sites (as the Rough guide notes) making a potent antidote to the trendy Ostalgie of Trabi kitsch. Here my experience of China, learning to empathize with “sufferers” there (Guo Yuhua, after Bourdieu), feels all the more relevant.

To limber up I took the U-Bahn to Alex, which I can’t presume to call by such a familiar name.

Alexanderplatz: the Weltzeituhr and Fernsehturm (1969), with the 13th-century Marienkirche—not leaning towers, more an innocent trompe-l’oeil of my camera…

My splendid host Ian Johnson (whose own writings are a must-read on both China and Germany) made a fine guide for a trip along the remnants of the wall, Checkpoint Charlie and so on.

We passed the Staatsoper, where I performed Elektra in 1980. How shamefully little I knew then, and how limited was my curiosity. Throughout my recent visit to Berlin it finally hits me how very pampered our lives have been compared to the painful decisions that our German contemporaries constantly had to make.

Do click on these links, from a fine series of short films tracing the timeline of the Wall:

- https://www.the-berlin-wall.com/videos/rent-dodging-in-prenzlauer-berg-1980-668/

- https://www.the-berlin-wall.com/videos/daily-life-in-the-divided-city-after-20-years-676/

- https://www.the-berlin-wall.com/videos/free-german-youth-gathering-in-east-berlin-662/

- https://www.the-berlin-wall.com/videos/popper-punker-and-teen-fashion-827/

Meanwhile Timothy Garton Ash was beginning his long acquaintance with the regime.

Stasi memorial sites

I visited both the Stasi prison and the Stasi museum. Though they’re not so far apart in the Lichtenburg district, I wouldn’t advise trying to do both in one day—the prison tour is excellent, and even by spending the rest of the day there I still only saw a small part of its exhibits. While the museum is less taxing than the prison, its location has retained a more suitably grim, bleak, forbidding air. As in Sachsenshausen, it’s wonderful that these sites are so busy, with many school parties—though I didn’t see any Chinese tour groups among them…

Just a few months before I was born, the major popular uprising of 17th June 1953 throughout the GDR (wiki, and a wealth of online sites, notably here), documented in both exhibitions, is far less known abroad than Budapest 1956 and Prague 1968. Needless to say, the popular uprisings of June 1989 in China are not so called there.

Studying the exhibits of perpetrators and victims, one continues to deplore the appalling ethical morass caused by Nazism—what a terrible price to pay throughout the following decades. Again, what would we have done?

Some of the eyewitnesses guiding visitors around the site.

At the Stasi prison (Gedenkstätte memorial) of Hohenschönhausen (formerly a Soviet special camp) the team of wonderful tour guides includes many former inmates; though our guide that day wasn’t among them, he gave us passionate articulate reminders of how crucially important it is to learn lessons amidst the current erosion of crucial rights worldwide.

Freya Klier and Stephan Krawczyk.

There were many strands to the counter-culture in literature and music. Icons of the resistance in the arts became figureheads, like singer-songwriters Wolf Biermann (b.1936, exiled in 1976) and Bettina Wegner (b.1947); Bärbel Bohley (1945–2010), whose 1978 painting Nude makes a striking image in the prison; performers Freya Klier (b.1950) and Stephan Krawczyk (b.1955); and Jürgen Fuchs (1950–99). For subversive film in the GDR, see here.

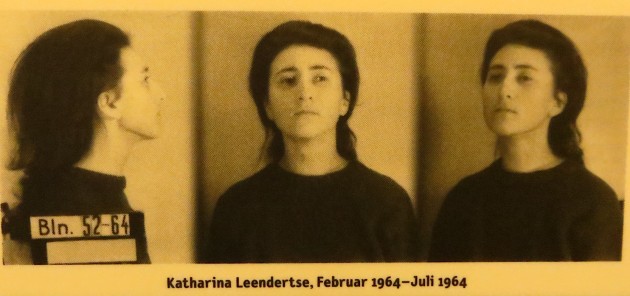

But just as moving in the prison is the series of mugshots of ordinary people making a stand, trying to escape, or just caught up in the maelstrom.

However much I admire our own posturing counter-cultural heroes, all this can only make them seem bland and smug. Sure, the punk movement in London, New York, and so on was important—more so than my life in early music, anyway, though that was also new (“original”!). But apart from getting abused in the Daily Mail, the punk life in the UK hardly involved such serious risks. For the GDR punks, [1] the “fascist regime” casually snarled by the Sex pistols would have had a far deeper resonance (cf. punk in Madrid, and jazz in Poland).

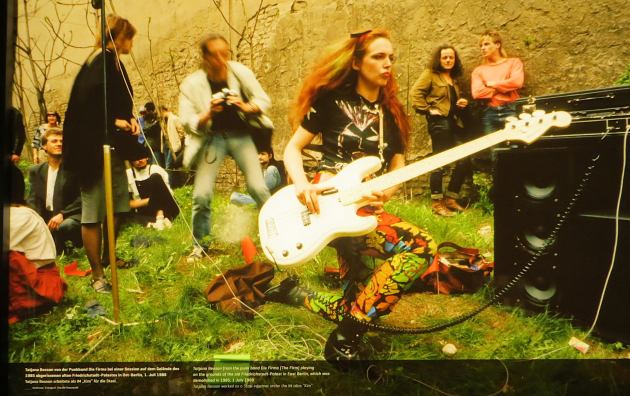

The Stasi museum also has exhibits on the vast network of IM informants—including punks. The Stasi even managed to recruit two of them in the band Die Firma—“it is not known whether they both knew each other’s secret”. Of course, the “decision” to inform, framed by self-preservation or desperation, and with whatever degree of apathy, was itself no simple matter.

Die Firma, with Tatjana Besson, 1988.

Here they are live in 1988:

Wedding at Jena, 1983: the couple’s friend was informing on them,

But the most basic routine parts of growing up were fraught with anxiety.

Alternative kindergarten, Prenzlauer Berg 1980–83.

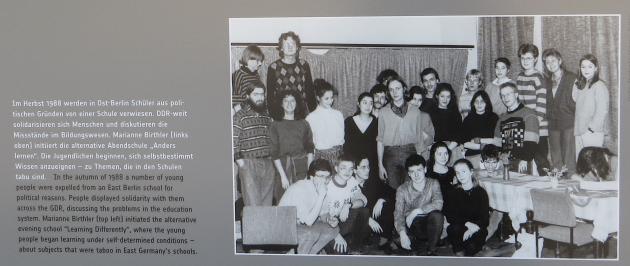

“Learning differently”, evening school 1988.

The Christian resistance was another crucial focus right through to the 1989 Montag demos that brought the whole system down. The pastor Oskar Brüsewitz burned himself to death in protest in August 1976—just as I was spending an idyllic summer after graduating (cf. Alan Bennett’s wry comment).

Also explored at the museum is the psychology of the Stasi employees.

The whole second floor of the museum preserves the offices of Erich Mielke, head of this whole hideous edifice. It’s a riot of beige and formica (cf. Deutschland 89, scenes of which were filmed there). Mielke’s diagram of the layout for his breakfast is a masterpiece of pedantry—of which, I have to say, my father would have approved.

The diagram has now been cannily immortalized in a mouse-pad, one of the few concessions to modernity in the museum’s suitably antiquated little bookshop—Is Nothing Sacred?

As throughout the socialist bloc (including China), for bitter relief, jokes always made a subversive outlet.

The museum also tellingly depicts the scramble of people all over the east to limit the destruction of Stasi files after November 1989.

* * *

It’s little consolation to reflect that the GDR was surely exceptional in its degree of surveillance, even in East Europe. And in such a vast and predominantly agrarian country as China, for all the horrors of Maoism, and the current intrusive mission, “the mountains are high, the emperor is distant”.

Again it’s worth citing Timothy Garton Ash:

Precisely because German lawmakers and judges know what it was like to live in a Stasi state, and before that in a Nazi one, they have guarded these things more jealously than we, the British, who have taken them for granted. You value health more when you have been sick.

I say again: of course Britain is not a Stasi state. We have democratically elected representatives, independent judges and a free press, through whom and with whom these excesses can be rolled back. But if the Stasi now serves as a warning ghost, scaring us into action, it will have done some good after all.

And again, I both recoil at this horror that was perpetuated right through my naïve youth, and admire the German determination to document it for future generations.

[1] Among a wealth of coverage of punk in the GDR, see e.g.

https://www.dw.com/en/you-should-be-gassed-what-it-meant-to-be-punk-in-east-germany/a-51163866

https://www.europavox.com/news/anarchy-e-u-east-german-punk/

https://www.jugendopposition.de/themen/145334/too-much-future-punk-in-der-ddr

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p056srhr

http://punkintheddr.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/post-1-ost-punkszene.html?view=sidebar

For the 1988 documentary Whisper & SHOUT, see here.

Pingback: Bearing witness 2: Sachsenhausen | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Lives under the GDR | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: A selection of recent posts | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Jottings from Lisbon 2 | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: China: commemorating trauma | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Guo Yuhua: Notes from Beijing, 3 | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: China and Europe: local society and politics | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Chet in Italy | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Europe: cultures and politics | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: New tag: Iron Curtain | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Guide to another year’s blogging | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Lives in Stalin’s Russia | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Life behind the Iron Curtain: a roundup | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Crime fiction: China and Germany | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Polish jazz, then and now | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Punk in Madrid | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: New musics in Beijing | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Punk: a roundup | Stephen Jones: a blog

Pingback: Verboten: GDR film, 1965 | Stephen Jones: a blog